At the April 11, 2024 Williams Foundation seminar, the former head of the Air Warfare Center and now Director General for Air Combat Capability, Air Commodore Ross Bender, addressed the way ahead for the RAAF in dovetailing with the new strategic focus of the Australian government.

Bender noted that the RAAF although closely partnered with other allies is focused on “conducting campaigns directed to the operational and strategic goals supporting national defense.”

It is focused in this sense, and increasingly on the region.

The speed and range of airpower is an essential contribution to the defense of Australia’s maritime interests.

As Bender put it: “The ADF must be able to operate across great distances to assure the security of our economic interests and be able to support our allies and partners. Air capability is vital to the maritime domain by providing the speed and responsiveness which it can deliver.”

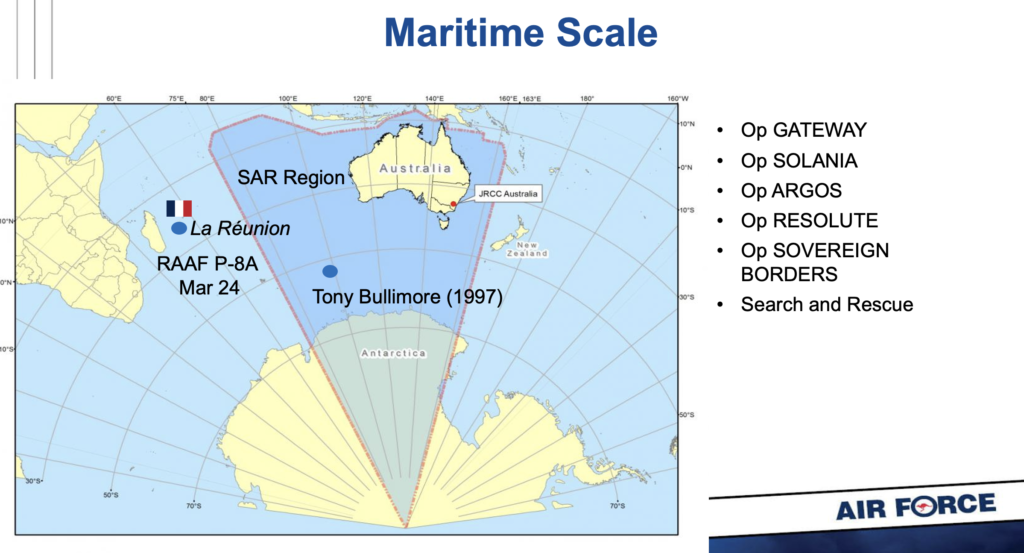

He provided a slide which reminded the audience of an aspect of the range and focus challenge.

He commented on this slide as follows: “And though we’ll discuss northern approaches, we should not forget the south with the Antarctic Treaty in mind, which from 2048, any of the parties can call for review. I also flag our contributions to some long standing and some relatively new maritime surveillance operations throughout our region, supporting the Australian Government and importantly, our regional partners.

“You might be aware of the Australian P-8 that recently visited La Réunion. Australia is a maritime nation and the ADF must be able to operate across great distances to assure the security of economic interests and be able to support our allies and partners.”

I would note that the ADF is truly dependent on what the RAAF can do as it provides both the air capability associated with the USAF in the United States as well as what the U.S. Navy provides for the U.S. military. It delivers strike, reconnaissance, maritime ISR and targeting data to the ADF. If the RAAF is not capable of performing its air delivered 360 degree capabilities, then the entire maritime domain defense enterprise for Australia is severely weakened.

In his talk, he discussed the need for the RAAF to develop its own version of agile employment which largely will evolve over ways to operate from the Northern areas of Australia where there are significant infrastructure and work force limitations. The challenge of fuel and logistical support to a distributed force is a major one to be met.

I would note that it has been announced that there is to be acquisition of AGM-158C LRASM anti-ship missiles to be carried on F/A-18Fs, P-8As and eventually F-35As, as well as AGM-158B JASSM-ER air-to-ground missiles. Another item is integration of the Kongsberg Joint Strike Missile on the F-35A. E/A-18G Growlers will receive 63 AGM-88E AARGM-ER missiles for attacking radars.

And as McInnes noted in his presentation, the range of these missiles in terms of effective attack is expanded by the operation of the air platform themselves.

Bender then discussed the coming of Triton to the ADF.

“Triton will operate from RAAF base Tyndall in the Northern Territory and be controlled from RAAF base Edinburgh in South Australia, a clear example of the new paradigm for the ADF and the Air Force. The platform is high cost, requires a highly skilled workforce to operate and maintain, but its capability is ideally suited for constant observation of our northern approaches.”

But the plan is to expand over time autonomous capabilities augmenting the manned and remotely piloted combat force.

Air Commodore Bender underscored: “Advanced autonomous concepts and capabilities, such as collaborative combat aircraft, can expand the projected envelope of high value, air or maritime assets, while extending their effective reach.”

A challenging and I personally believe costly effort that is not fully recognized in realistic budget discussions is simply adapting the RAAF to new operational conditions and contexts.

This is how Air Commodore Bender put It: “There must be important efforts to address a challenge in operating force in Australia. We can’t consider our bases as sanctuaries anymore, disconnected from the support base in Australia. How do we continue to operate and demonstrate resilience and maintain the initiative to support deterrence?

“The Air Force is adopting an agile operations concept of a maneuver across a dispersed and hardened network of bases. Of course, this approach must include the measures we can take through the development of integrated air and missile defense capabilities. This protection also requires an understanding of own force signatures, and the automated threat environment, including to supporting and enabling elements.

“An agile posture increases deterrence by being strategically predictable, but operationally unpredictable. Strategic predictability comes from ensuring potential adversaries are left under no doubt about our resolve to ensure survivable, resilient, and enduring airpower operations. Agility at the level we think necessary requires new approaches to combat support, logistics and command and control.

“At its heart, an agile operations concept provides a network of air domain access points to enable aircraft to move rapidly to enable us to aggregate effects, and then disaggregate and reconstitute to complicate advisory targeting. Agile operations enable the resilience of our airpower.”

But what is the challenge in moving ahead with such a vision?

What follow are my own thoughts and not those of any speaker during the day of the Williams Foundation seminar from the ADF.

The reality is that the government is cutting airpower in favor of its investments in the future maritime force, notably SSNs and the future surface fleet. This leaves clear gaps with regard to the enhancing of ADF capability in the crucial three-to-five year period facing the ADF.

Government documents and officials have embraced the notion that Australia’s warning time is significantly reduced but the reality is that the government is cutting current capability to pay for a force 10 years away.

One needs to be clear.

The decision to cut funding for the fourth squadron of F-35s is a significant reduction in capability. Notably, when one considers the range at which F-35s operating as an allied fleet can move data for targeting, eliminating the numbers of aircraft have an impact.

And the RAAF F-35s are capable of integration with those of the USAF and in fact now operate in such a manner. This is not interoperability but integratability which is a very unique contribution delivered by the F-35 across the ADF and U.S. militaries fleet of F-35s, USMC, US Navy and USAF.

This is simply not true of a legacy aircraft like the Super Hornet, for in fact that is why the ADF was buying the F-35 in the first place.

And air autonomous systems are not a solution for the three-to-five-year period in and of themselves but might become useful adjuncts as ISR or C2 nodes in a kill web especially as Triton comes on board. There could be accelerated capability to move data from Triton to loyal wingman operations if there is an operational and budgetary space for the USE of autonomous systems prioritized by the government in the three-to-five-year period.

And the work on the Australian approach to agile combat employment is a priority but will be costly up front and require new working relationships between Army and the RAAF as well.

In an interview I did last year with John Blackburn with Air Vice-Marshal Darren Goldie, then the Air Commander of the RAAF, we discussed the challenge of re-focusing the force:

“We don’t have the level of knowledge and normative experience we need to generate regarding infrastructure across Western and Northern Australia for the Australian version of agile combat employment.”

He contrasted the Australian to the PACAF approach to agility. The USAF in his view was working on how to trim down support staff for air operations and learning how to use multiple bases in the Pacific, some of which they owned and some of which they did not own.

The Australian concept he was highlighting was focused on Australian geography and how the joint force and the infrastructure which could be built — much of it mobile – could allow for dispersed air combat operations.

This meant in his view that “we need to have a clear understanding of the fail and no-fail enablers” for the kind of dispersed operations necessary to enhance the ADF’s deterrent capability.

A key element of this is C2. Rather than looking to traditional CAOC battle management, the focus needs as well to focus on C2 in a dispersed or disaggregate way, where the commander knows what is available to them in an area of operations and aggregate those forces into an integrated combat element operating as a distributed entity.

Goldie commented: “We are developing concepts about how we will do command and control on a more geographic basis. This builds on our history with Darwin and Tindal to a certain extent, although technology has widened that scale to be a truly continental distributed control concept.

“We already a familiar with how an air asset like the Wedgetail can take over the C2 of an air battle when communications are cut to the CAOC, but we don’t have a great understanding of how that works from a geographic basing perspective. What authorities to move aircraft, people and other assets are vested in local area Commanders that would be resilient to degradation in communications from the theatre commander – or JFACC?

“We need to focus on how we can design our force to manoeuvre effectively using our own territory as the chessboard.”

Air Vice-Marshal Goldie underscored that the ability to work with limited resources to generate air combat capability is exercised regularly by the normal activity of 75 Squadron, flying F-35s in Australia’s Air Combat Group. This squadron operates from RAAF Base Tindal in the Northern Territory and as Goldie put it: “they have to operate with what they have in a very austere area.”

He highlighted a recent exercise which 75 squadron did with their Malaysian partners. The squadron operated their F-35s, and each day practiced operations using a different support structure. One day the operated with a C-27J which carried secure communication, along with HF communications systems and dealing with bandwidth challenges each bearer posed.

Another day they would operate with a ground vehicle packed with support equipment and on another day they would operate without either support capability. The point being the need is to learn to operate in austere support environments and to shape the skill sets to do so.

By learning how to use Australian territory to support agile air operations, and to take those capabilities to partner or allied operational areas, Australia will significantly enhance its deterrent capabilities going forward. This is a key challenge being squarely addressed by the RAAF.

So what can be achieved in the near to midterm along these lines?

In my view, this is a key measure of the credibility of Australian deterrence by denial or whatever other term you might use.