In this video, the CO of the USS Ford provides on update on the USS Ford.

And focuses on onboard fire fighters.

08.14.2020

Video by Chief Petty Officer RJ Stratchko

USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 7

In this video, the CO of the USS Ford provides on update on the USS Ford.

And focuses on onboard fire fighters.

08.14.2020

Video by Chief Petty Officer RJ Stratchko

USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 7

By Robbin Laird

During my visit to NAWDC in early July 2020, I had a chance to continue discussions begun earlier in the year with the CO of NAWDC and his senior officers.

Rear Admiral Brophy had highlighted as one major change at NAWDC from the time when I had last visited was the complete revamping of the strike syllabus at NAWDC. And he credited the work of CDR Papaioanu (N-5 Strike Department Head) with leading the effort in re-designing the strike syllabus.

Prior to becoming the N-5 Department head, he was the CO of TOPGUN, which he explained to me was a normal progression. He underscored that “this was the first major rewrite of the strike syllabus at Fallon in more than twenty years.”

This was being driven by the shift from the land wars to great power competition and the need to operate in a fluid extended battlespace. As CDR Papaioanu put it: “The level of modern warfare is nothing like we have seen before. We are talking about extraordinarily intense capabilities across a broad spectrum of warfare.”

How to fight effectively in such conditions? According to CDR Papaioanu: “The key to the modern fight is an ability to integrate an effective force package.”

The strike syllabus has been redesigned to work a combat force able to “integrate an effective force package.” Clearly, the coming of the F-35 is part of the technological stimulus to such a rethink and redesign, as I have argued for many years, fifth generation aircraft in the force drive its renorming.

But it is also part of a significant change in how C2 and ISR is being used to shape the approach to strike as well. As discussed with CDR Fraser, head of the information warfare department, dynamic targeting is a key capability which the fleet needs to be able to deliver.

The new strike syllabus is designed in large part to deliver a dynamic targeting capability.

According to CDR Papaioanu, the redesign was driven by inputs from the theater commanders with regard to what they wanted from Naval Aviation in the context of the strategic shift to the high-end fight. Based on feedback from the theater commanders, they began the process of reworking the curriculum. He and his team worked closely with COCOM planning staffs in thinking through the redesign.

The fleet is a key enabler of combat flexibility. “We are the 9/11 force for the nation, so we have to be able to be able to operate across a spectrum of conflict, including higher end missions.”

As he described a key driver of the change has been with regard to the ISR enablement of the fleet. They are focused increasingly on the left side of the kill chain, and leveraging ISR assets to be able to do so. In the kill chain focus, the priority emphasis has been upon target and engage with a priority training focus on targeting.

“Now we need to focus much more on the find, fix and track functions. And we need to pay more attention on working with ISR assets to work the left side of the kill chain, and we have altered the syllabus to enable training to work the left side of the kill chain more effectively.”

In my terms, this is a shift from a kill chain to a kill web focus. In a kill web focus, the ISR assets which will help determine how the force package if formed, shaped and executes may or may not be organic parts of a pre-defined task force.

In terms of training, the syllabus emphasizes a couple of core changes. First, is the clear focus on mission command. “We take the mission commanders and challenge them to think through how various assets could be used in an ISR enabled strike package? How will they use the range of capabilities available? How can I as a strike commander take advantage of the sensors on a P-8? How do I ensure that I am getting the kind of information from a platform at the time I need it to execute my mission?”

As he explained the shift, the goal of the new syllabus is to address the paradigm shift with regard to ISR integrability into the strike force. The syllabus is designed to be flexible enough to bring in a variety of assets to empower the mission commander and his strike force.

And it is very clear, that the shift in training which CDR Papaioanu described is part of a broader change in the training function. Training in the new syllabus is highly interactive with real world evolution of combat capabilities and operations. This generates and a continuous learning cycle for training from ops to training to development and back to ops.

For the story of the featured image, please see the article about CDR Papaioanu.

“The National Naval Shipbuilding Enterprise is an ambitious nation-building project that will deliver cutting-edge capabilities to the Royal Australian Navy while creating thousands of jobs and building Australian industry.

“The Enterprise is on track, with a modern new shipyard nearing completion in South Australia, patrol boats and Offshore Patrol Vessels under construction in Western Australia and South Australia, and the design of new Hunter class frigates and Attack class submarines progressing well.”

For our report on the Offshore Patrol Vessel program as a lead into the new approach to the Australian Shipbuilding Enterprise, see the following:

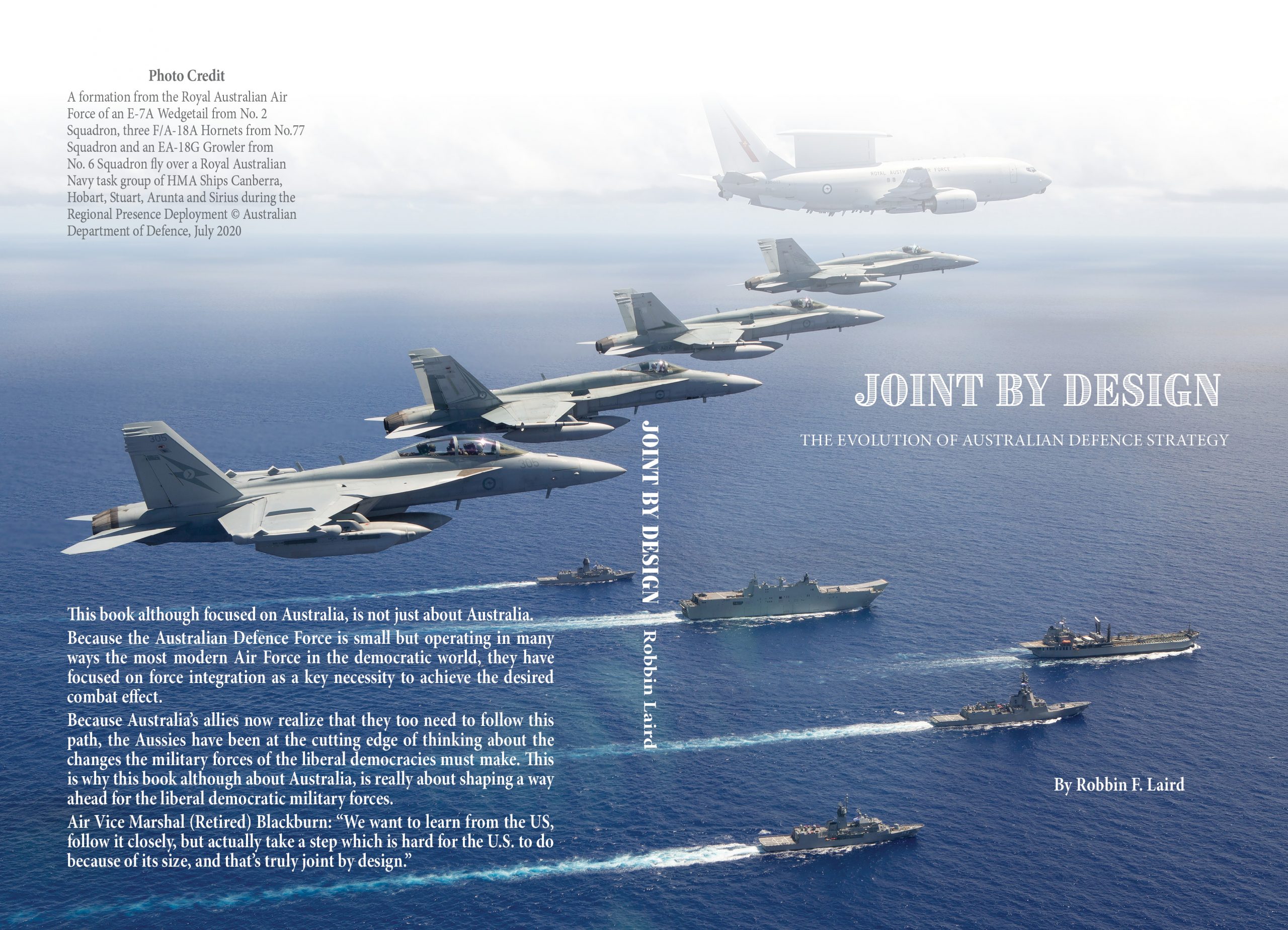

We have an upcoming book on Australian defence strategy and policy to be published this December.

Joint By Design: The Evolution of Australian Defence Strategy

In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, the prime minister of Australia, Scott Morrison, launched a new defense and security strategy for Australia. This strategy reset puts Australia on the path of enhanced defense capabilities.

The change represents a serious shift in its policies towards China, and in reworking alliance relationships going forward. “Joint by Design” is focused on Australian policy, but it is about preparing liberal democracies around the world for the challenges of the future.

The strategic shift from land wars to full spectrum crisis management requires liberal democracies to have forces lethal enough, survivable enough, and agile enough to support full spectrum crisis management.

The book provides an overview of the evolution of Australian defence modernization over the past seven years, and the strategic shift underway.

By Robbin Laird

This week the Navy’s Airborne Command and Control Community celebrated the 60th anniversary of the first E-2 flight.

According to a story released by the public affairs team from Naval Air Force Atlantic:

“While the U.S. Navy celebrated its 245th birthday this October, the Airborne Command & Control Logistics Community marked a longevity milestone: the 60th anniversary of the maiden E-2 flight, Oct. 21, 2020.

“On Oct. 21, 1960, the first flight of the E-2A occurred out of Bethpage, New York. Five years later, on Oct. 19, 1965, the U.S. Navy conducted its first E-2 deployment.

“For 60 years, the E-2 has been the eye in the sky for the U.S. Navy,” said Capt. Michael France, Commander, Airborne Command & Control Logistics Wing, who has flown more than 4,700 hours flying 25 different aircraft. “The E-2 has continued to manage the airspace in both times of peace and in times of conflict, and we are grateful for every pilot, maintainer, and aircrew who have supported this community.”

The Commander of the Naval Air Force Atlantic, Rear Admiral Meier, discussed the history of the introduction of the Hawkeye into the carrier air wing with the current Commander of the Airborne Command and Control Logistics Wing, Captain Michael France.

In that podcast, Captain France started by going back to the test pilot who flew that first flight.

“21 October 1960 was the first flight of the E2 back then. It was known as the W2F or the Willy FID. And that first flight was formed by a guy named Tom Attridge and that name may sound familiar to some that’s the same gentleman who flew the F-11 and as a test program. And he’s the guy that shot himself down by going supersonic and flying faster than his bullets. And he ended up ditching in the field because of that. So that’s the same gentleman that flew the first flight of the E2 back in 21 October 1960.”

The discussion then turned to the way ahead for the airborne C2 community with regard to the various transitions which they are undergoing,

As Rear Admiral Meier put it:

“I think it is a fascinating time for the E2 community, for the whole community with the advent of the E2D is absolutely a game changer. And I’m wondering if you can talk about the role that the E2 takes on and the role that is evolving to include as we’ve discussed previously, your community’s busy with a lot of transitions and a whole lot of improvements which as a test pilot yourself has got to be just fascinating to be involved at as the Commodore.”

Captain France responded:

“We’re involved intimately in three significant transitions right now. We are to E2C to E2D currently about 50%, a little over 50% of transitioning squadrons from the C to the D as well as moving from E2D to E2DAR or area or fueling. That is why we built the E2D was to get Airborne and stay on station.

“And now we’ve transitioned our first squadron VW1-26 in Norfolk, Virginia, to the AR version. The mission systems in the back where the third transition we’re going through right now, going from disc two to disc three. So if you think about the E2D as it stands today, from where we were an E2D with air refueling and the disc three Modd is really why we built this aircraft.

“If you think long range detection and you think persistence on station with air refueling, this aircraft has been around for 60 years and some of the guys in the program say it’s going to be around until 2050. So think about possibly 90 years of flying this airplane. But that’s why we built this airplane. And it has proven itself from in major combat operations from the Vietnam war to Libya, the Gulf war. And it’s going to be around for the foreseeable future.

“When you talk about air refueling and being on station, we’re really moving in the direction of having a tracker that can track it range, but we can do things in the Multi-Domain fashion. We can bring multiple sensors into the aircraft and we can distribute information to the people that need it making so that they can make real time decisions about what they’re seeing.

“Also, we know we’re not just improving the mission systems, but as a test pilot, I’m heavily involved in championing programs, like a PLM type of system that we can put in our airplane that will help our pilots who have been out there doing that mission for eight, nine, 10 hours.

“After doing that air refueling task as well, coming back to the ship at night, bad weather pitching deck and getting some augmentation in the airplane, that’ll help them bring this aboard, bring this aircraft to aboard safely.”

The conversation then moved into the key area which we refer to as shaping kill web information distribution and C2 in the distributed battlespace.

Rear Admiral Meir underscored that “where I see the future of warfare going is the fusion of sensors and imagine unmanned aerial vehicle operating a couple hundred miles from a surface unit passively detecting the system, relaying that information then to that surface unit, which then plugs that into this network and shares amongst perhaps Marine shore-based, shore batteries, other surface ships, aviation units, fleet headquarters, all of those such that the best decisions with that information can be made.

“And those decisions may be to monitor that target. It may be to gather more information, or it may be to hold that target at risk. And that is absolutely where E2D plays such a vital role.”

A key issue in all of this is how naval integration intersects with joint or coalition force integration, which is a key work in progress, but clearly a force multiplier and enabler

This is how Rear Admiral Meier highlighted this challenge:

“You mentioned JADC-2 earlier, and that’s an interesting topic because that’s an air force led initiative joint, all domain command and control and everything that we’re doing in the Navy is intended and designed such that it will be both independent, which is the great strength of our carrier strike groups, our maneuver warfare, or lethality at range.

“We talked about the endurance of whether it’s E2 or others as a result of our refueling, but it is that maneuver lethality is a combination if you will, of the aircraft but also that independence of the aircraft carrier and then plugging completely in the JADC2 such that everything that the carrier is absorbing, learning and vacuuming up can then be plugged into the whole command and control network.”

In my visit to NAWDC earlier this year, I focused very much on the C2/ISR dynamics of change and how the airwing of the future was really best described as the integratable air wing. My interview with CDR Christopher Hulitt, then head of CAEWWS, the Navy’s airborne command & control weapons school located at Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center (NAWDC) at Naval Air Station Fallon, provided a wide-ranging perspective on the way ahead for his community.

This discussion provides a useful compliment to the discussion between Rear Admiral Meier and Captain Michael France.

One of the key points which emerged in the discussion with CDR Hulitt was the following:

“With the coming of the F-35 to the carrier wing, there is a broader shift in working diverse sensor networks to deliver the combat effect which extended reach sensor networks can empower. At Fallon, they are working the relationship between the F-35 and the E-2D and sorting through how to make optimal use of both air systems in the extended battlespace. Commander, Airborne Command & Control and Logistics Wing and Carrier Air Wing Two and are moving forward with a new initiative, the First Integrated Training Evolution (FITE), which will provide basic, tailored integrated training incorporating E-2D(AR) and F-35 paired with fourth generation platforms.

“It is about deploying an extended trusted sensor network, which can be tapped through various wave forms, and then being able to shape how the decision-making arc can best deliver the desired combat effect.”

The podcast of Rear Admiral Meir and Captain France can be listened to below:

Featured Photo: An E-2C Hawkeye assigned to the “Bear Aces” of Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron 124 lands aboard the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt and Carrier Air Wing 8 are operating in the U.S. 5th Fleet area of responsibility.

The AH-1W Super Cobra participates in its Sundown flight at Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base, New Orleans on Oct. 14, 2020.

After an incredible 933,614 flight hours over a 34 year career, the AH-1W “Whiskey” Super Cobra flew its last flight over the City of New Orleans passing its legacy and mission to the “Zulu” variant, the AH-1Z Viper.

The “Zulu” will carry the torch of its predecessor, continuing to enable Marine Forces Reserve to go, fight, and win our nation’s battles through air superiority.

BELLE CHASSE, LA, UNITED STATES

10.14.2020

Video by Lance Cpl. Christopher England

Marine Forces Reserve

By Robbin Laird

October 3, 2020 is German Unity Day.

This is a very significant date in history, which changed the face and fate of modern Europe.

The face is clear; the long term impact on the fate of modern Europe is not.

I have spent much of my life involved in various aspects of working the ground for German unification, with substantial time spent in Europe in the 1980s dealing with the Soviet challenge to Europe.

And during my visit to Berlin in 2018, I looked back at the events of 1989.

This was the piece published on November 11, 2018.

I am in Berlin today for the International Fighter Conference 2019 which starts tomorrow.

I took the opportunity to revisit Checkpoint Charlie.

It is now a museum, but also a testament to the will of the West to defend liberal democracy against the Soviet Union.

I often visited West Germany in the 1980s when the political warfare over Euromissiles was a dominant reality.

The U.S. President was hardly popular and when you visit the Checkpoint Charlie museum it is easier to find remembrance of JFK’s visit than the historical moment when President Reagan challenged the Soviet leaders to “teardown that wall.”

I set up a working group in the mid-1980s at the Institute for Defense Analysis to discuss the prospects and how to shape a possible German reunification.

It was not a widely attended effort, but did prepare the way for the historical events.

The key agreement of the group was that if the new Germany was not part of the Western institutions, the European Union and NATO, then any agreement with the Soviets would not be worth the effort.

The concept in those days was that only an agreement that yielded a real outcome which could fit into the values of the liberal democracies really mattered.

Simply having an agreement to look like progress was being made was the wrong way to go because it would only help the authoriarians working to undercut consensus in our societies.

Seems a long time ago.

There was no desire to have a Soviet veto power over the future of Germany.

The Russians frequently insist that they had promises with regard to the fate of sovereign states in Europe; that somehow they had a veto power over which states could work with the West and which could not.

That simply is not true.

And that brings us to Berlin, East and West.

West Berlin was a fragment of liberal democracy in a sea of Soviet and East German authoritarianism.

The Stasi was a prevalent force and provided the atmosphere for any Western visitors to the “workers paradise” which could could be seen in East Berlin.

My first job in the Pentagon was to work for a man who had just served as the Brigade Commander in Berlin.

According to Wikipedia:

“The Berlin Brigade of the United States Army was a separate brigade based in Berlin. Its shoulder sleeve insignia was the U.S. Army Europe patch with a Berlin tab, later incorporated.”

I functioned as his tutor on things Soviet and we had many discussions about his time in Berlin.

What impressed the most was the dedication of the Brigade.

As the General put it: “We are a speed bump which would be crushed as the Soviets prepared to move against the inner German border. But we need to do so in a way that would remind them that the United States was not going to yield an inch of German territory without a fight.”

Put in simple terms: “We are going all to die in a conflict; we need to do so with and for a purpose.”

That kind of courage and dedication can be forgotten when visiting Berlin today.

Turning Checkpoint Charlie into a museum is clearly a reminder of what U.S. servicemen and women contributed to the future of Germany.

But turning it into a museum and remembering the 30 year anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall also recalls the lessons learned from the Armistice Day being remembered in Europe.

The “war to end all wars” didn’t.

And the Fall of the Berlin Wall did not end to the East-West conflict.

And the 2008 and 2014 territorial seizures by Russia are clearly a reminder, that there are no wars that end all wars.

Checkpoint Charlie may be a museum; but it is a reminder that the East-West conflict is hardly over.

2014 is as significant as 1914 but simply has not been recognized as such.

In the video below, by Senior Airman Kelsey Cook, Regional Media Center AFN Europe released on October 2, 2020, the importance of this day and the events that led to the reunification of Germany.

USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) conducts underway flight operations during its 2020 deployment. Ronald Reagan, the flagship of Carrier Strike Group 5, provides a combat-ready force that protects and defends the United States, as well as the collective maritime interests of its allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific region.

INDIAN OCEAN

10.10.2020

Video by Petty Officer 2nd Class Erica Bechard

USS RONALD REAGAN (CVN 76)

By India Strategic

Tel Aviv/ Abu Dhabi. Etihad Airways, the national airline of the UAE, has become the first GCC carrier to operate a commercial passenger flight to and from Israel.

The historic flight, operated by an Etihad Boeing 787 Dreamliner aircraft, was flown in partnership with the Maman Group, and landed at around 7 a.m. It took off a few hours later for the three-and-a-half-hour journey from Israel to the UAE.

“Today, we make history. Etihad has become the first Gulf airline to operate a passenger flight to Israel. And this is only the beginning… Salam and Shalom!” Etihad Airways tweeted.

“Shalom Tel Aviv! Thank you for the very warm welcome to #Israel,” it said in another tweet.

On board the return flight was a group of tourism industry leaders, key corporate decision makers, travel agents, and cargo agents, along with the media to experience Abu Dhabi and the wider UAE, at the invitation of Etihad Airways and representatives of Abu Dhabi’s tourism industry.

This is the latest development in a growing cooperation between the two nations following the establishment of diplomatic ties, and the signing of the Abraham Accords between the UAE and Israel in Washington D.C. on September 15. It also follows Israeli national airline El Al’s first symbolic commercial flight between Tel Aviv and Abu Dhabi on August 31.

His Excellency Mohamed Mubarak Fadhel Al Mazrouei, Chairman, Etihad Aviation Group, said: “Today’s flight is a historic opportunity for the development of strong partnerships here in the UAE, and in Israel, and Etihad as the national airline, is delighted to be leading the way. We are just starting to explore the long-term potential of these newly forged relationships, which will be sure to greatly benefit the economies of both nations, particularly in the areas of trade and tourism, and ultimately the people who call this diverse and wonderful region home.”

As an important facilitator of trade, the flights between Tel Aviv and Abu Dhabi will also carry commercial cargo sourced from, and destined for, points across Etihad’s global network, in addition to commercial guests.

Etihad has also become the first non-Israeli airline in the Middle East to launch a dedicated website for the Israeli market in Hebrew. Also available in English, the Israeli version of the airline’s official website contains digital content including extensive information on Etihad’s operations, product, services, and network.

The site also includes an Abu Dhabi destination guide.

The site can be viewed in Hebrew at www.etihad.com/he-il and in English at www.etihad.com/en-il.

As the UAE’s national carrier, Etihad Airways is one of the world’s leading airlines, acclaimed for its unparalleled service, industry leading cabins, and genuine Arabian hospitality.

Published by India Strategic on October 19, 2020.

This flight was the next step after the first commercial flight occurred on October 18, 2020 with Flight#LY973 from Tel Aviv, Israel, to Manama, Bahrain.

The El Al flight LY973 took off from Israel’s Ben Gurion international airport in the capital Tel Aviv at 11:19am local time and landed in the Bahraini capital Manama at 1:33pm local time, according to flight tracker FlightRadar24.

The airliner carried a delegation of US and Israeli officials that were traveling to Bahrain to sign a normalization declaration formally launching full diplomatic relations between the two countries. US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s national security adviser, Meir Ben-Shabbat, are leading the delegation, according to the US Treasury Department.

And after landing in Manama, Barhrain.