A key part of the direct defense challenge being faced in Europe today is political warfare with the 21st century authoritarian powers.

And a key policy instrument being used by both Russia and China WITHIN European states is disinformation guided by an ability to connect that disinformation with the defense efforts of European allies participating in joint defense efforts.

At the International Fighter Conference 2019, the head of the Lithuanian Air Force highlighted how the Russians were directly intervening within Lithuanian affairs to present disinformation as “facts” about what the allies of the Baltic states were doing to shape a collective defense effort.

As noted in an article we published about the International Fighter Conference:

Col. Dainius Guzas, Lithuanian Air Force Commander, provided a briefing entitled “Developing Capability Against a Peer Opponent.”

The challenge as described by Guzas was both the direct threat posed by Russia against the Baltics and the use of political warfare to undercut the core defense of Lithuania – the engagement of NATO allies in Baltic Air Policing and the delivery of air defense to Lithuania via NATO coalition airpower.

Because of the significant number of NATO air policing participants in the Baltic Air Policing effort, Lithuania was a host nation to a wide variety of NATO forces.

This means that they probably have experienced more first-hand knowledge than most of the challenge of operating the range of NATO fighter aircraft at the tactical edge in NATO defense.

This NATO engagement experienced first-hand by the Lithuanian Air Force provides the ground truth for how to defend the Baltics in a crisis

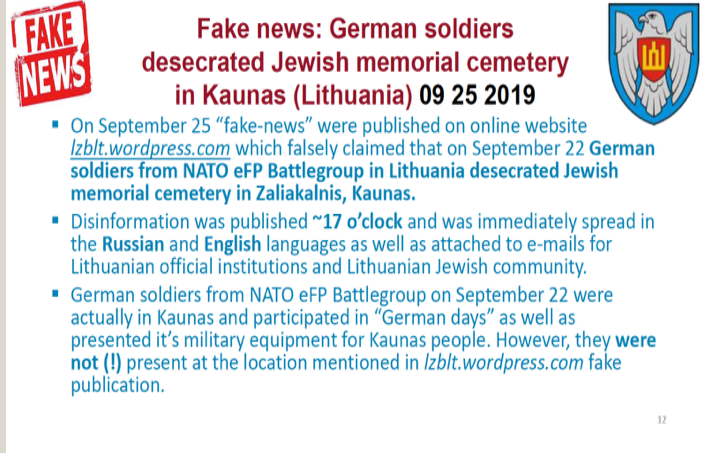

And the Russians have spent considerable time and effort in generating “fake news” to try to undercut the confidence of Lithuanians in their NATO allies.

This form of political warfare is combined with air space incursions to try to test and pressure the Baltic Republics.

Three slides from Col. Guzas’s briefing can be seen in the slide pack below, which illustrate his discussion of Russian airspace violations, the NATO participants to data in Baltic Air Policing, and an example of Russian “fake news” designed to undercut the confidence of Lithuanians in their NATO allies.

One can go to the article and see all of Col. Guzas’s slides but the one below captures the challenge being posed:

Recently, the well respected Canadian defense journalist, Murray Brewster, highlighted a similar challenge posed for Canadian forces operating in support of Baltic defense.

“The Canadian-led NATO battle group in Latvia was the target of a pandemic-related disinformation campaign that alliance commanders say they believe originated in Russia.

“Reports circulated recently in some Baltic and Eastern European media outlets that suggested the contingent at Camp Adazi in Kadaga, outside the capital of Riga, had “a high number” of cases of the deadly virus.

“That was definitely not true,” said Col. Eric Laforest, commander of Task Force Latvia.

“When the reports first surfaced, ahead of a major exercise late last month, the Latvian defence ministry swung into action to counter the false information.

“The Latvian authorities here were the ones to set the record straight because it was information about troops stationed in their country,” said Laforest. “Rapidly, within a matter of a few hours, they went out and explained what the situation was. It actually happened fairly fast.”

Brewster added:

“The propaganda campaign directed at NATO troops emerged around the time they were engaged in a training exercise which took them just outside their base.

“Known as Exercise Steele Crescendo, the training involved troops and tanks simulating defences against an armoured attack on the Baltic country.”

Also, see the following:

Information Warfare and the Authoritarian States: How Best to Respond?

We deal with this type of political warfare as a key part of the challenge for direct defense of Europe facing the 21st century authoritarians in our forthcoming book.

https://products.abc-clio.com/abc-cliocorporate/product.aspx?pc=A6252C