The Dwight D. Eisenhower and Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Groups conducted dual carrier and joint air wing operations with a B-52H Stratofortress in the Arabian Sea March 21, 2020.

ANDAMAN SEA

03.21.2020

USS Harry S Truman

The Dwight D. Eisenhower and Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Groups conducted dual carrier and joint air wing operations with a B-52H Stratofortress in the Arabian Sea March 21, 2020.

ANDAMAN SEA

03.21.2020

USS Harry S Truman

By Robbin Laird

With a growing array of single service initiatives designed to compete for “deterrence badges” in the great power competition, there is a clear danger of splintering deterrence rather than reinforcing it.

In my recent discussion with Dr. Paul Bracken, the nuclear weapons expert, underscored the key importance of the nuclear equation when shaping a deterrent approach to Russia or China.

And with many top military leaders having lived through a period of land-centric wars where this was simply not a consideration, it is not about remembering, it is about fundamentally rethinking how the nuclear aspect is woven into a deterrent strategy and understanding the challenges of deterrence in a second nuclear age.

An additional challenge is when single services put a bid out into the budget world for putting containerized missiles covertly into the first island chain (China) or building a 1,000-mile gun without being woven into an overall military strategy which is closely integrated into a global great power strategy.

Recently, I discussed this overall challenge of context and integration with Lt. General (Retired) Deptula who has been associated with us from the beginning and is now Dean, of the Mitchell Institute of Aerospace Studies.

Question: How do you view the impact of the Coronavirus crisis on the way ahead for U.S. military strategy and force structure modernization?

Deptula: Obviously, defense spending will become tighter which means that we need to do a much better job of making strategic, rather than service constrained, investment and force structure development decisions.

We cannot have dangling participles like the Army’s 1,000-mile gun or the Marine Commandant’s cruise missile initiatives unrelated to overall military strategy.

And the COVID-19 virus clearly is introducing major geopolitical changes as well which we need to adjust strategy to deal with both in terms of new opportunities and new challenges.

Notably, the crisis has had a clear impact on European Union cohesion, on China’s role in the world and on the viability of the regime in Iran.

How should we deal with such changes as part of our overall national strategy?

And within that question is another on how do geopolitical shifts affect our military strategy?

Question: Where do you see specific impacts on the U.S. military?

Deptula: The U.S. military has just about come out of the significant readiness shortfalls they were dealing with prior to the funding infusion of the past three years.

Now readiness is being hit again both by the impact of the crisis and then the need to ramp up after the initial effects.

COVID-19 does raise questions about the vulnerability of large deck carriers, in terms of the impact of disease at sea on combat availability. There are more people who tested positive for COVID-19 just on that one ship, the USS Roosevelt, as have tested positive in the entire United States Air Force.

And the tight budget situation coupled with geopolitical changes clearly requires shaping a comprehensive military strategy which supports national strategy shaped to deal with those geopolitical changes.

At the heart of the challenge is the requirement to make strategic decisions about force structure development which align with strategic need, rather than separate force structure modernization.

A case in point is that the USAF is sunsetting B-1s and B-2s because of constraints within the USAF budget and choices that have to be made in terms of investments. But strategically, the flexibility of the bomber force, as well as its capability to deliver significant strike capability into an area of interest is strategically important.

We need to move toward an evaluation system inside the Department of Defense that looks at desired outcomes across all service programs to invest in those that give us the greatest effect for the least amount of resources involved. One B-2 or two B-1s can deliver the same amount of ordinance at range as an entire carrier battle group. There are 5,000 people on an aircraft carrier but only two crew members in a B-2. The problem is that we only have 20 B-2s.

And we clearly need to build out our capability to deal with the strategic disinformation our adversaries are generating in the current environment.

China is now on a campaign to benefit from the pandemic and strengthen its competitive position with the U.S. So what cabinet level organization in the United States government is responsible for coming up with strategic communications and information to counter this kind of an effort? The answer is there is none, so we’ve got to fix that and we’ve got to fix it quickly.

Question: Let us go back to the nuclear issue and the need as well to reshape the joint force to deliver its most capable tactical and strategic effect.

How best to do that?

Deptula: Clearly, we need to implement the new nuclear strategy, and notably insure that the standoff weapons piece in the modernization program is fully funded, both for today’s bomber force and for the B-21.

And, for me, shaping the comprehensive C2/ISR integratability piece is crucial, which I refer to as the combat cloud.

If we can get to that kind of a vision for joint force operations then no service like the Army or the Marine Corps needs to feel that they have to justify their relevancy, but they’re part and parcel of an entire panoply of capabilities that’s formed by this intelligence surveillance, reconnaissance, strike, maneuver sustainment complex that’s extraordinarily difficult for any adversary to derail.

Even if an adversary is able to take out a couple of elements of the combat cloud, the rest of the elements re-form and re-heal and continue to operate.

It’s the diversity of domains and particular threats coming from each of those domains, air, sea, land, space, subsea, that will complicate an adversary’s calculus, which is crucial to achieve deterrence.

The problem of achieving deterrence is that it is an intangible.

And so people have a difficulty putting their hands on it, when in fact it’s the most cost-effective means to avoiding conflict and win it, because you’re winning without having to fight.

And this requires for us an ability to integrate nuclear weapons into this strategic calculus.

The featured photo B-2 Spirit joining up on FORCE 26 – 305th AMW KC-10 just after midnight in the skies over southwest Missouri.

MH-60R ‘Romeo’ helicopter may not be a stealth platform, but it has become a globally used platform by the US Navy and U.S. allies and has done so in barely noticed fashion.

Globally is a key aspect of a platform, even with different systems onboard common platforms, common logistics and platform support across the demanding maritime environment is a clear plus for the US Navy and the global partners with whom they work.

In a recent article published April 7, 2020 by the Royal Australian Navy, LEUT Geoff Long (author), ABIS Jarrod Mulvihill (photographer) highlighted the coming of the Romeo to its latest ship, HMAS Adelaide.

HMAS Adelaide has left its home port in Sydney to conduct First of Class Flight Trials for the MH-60R ‘Romeo’ helicopters off the coast of Queensland.

The trials will determine the safe operating limits of the Romeo helicopters on the Landing Helicopter Dock (LHD) in a range of sea states and wind speeds at both day and night.

Adelaide’s Commanding Officer, Captain Jonathan Ley, said the training was essential to ensuring Navy maintains its readiness to conduct Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief operations in support of the Australian public and our neighbours if required.

“The results will provide a new standard of operational capability, informing how Navy can employ the MH-60R and LHD together in the future to increase both lethality in combat, and responsiveness during humanitarian assistance and disaster relief tasks,” Captain Ley said.

The Australian Defence Force is supporting Whole-of-Government COVID-19 efforts while maintaining operational preparedness.

Captain Ley said Navy had put in strict measures on its ships to ensure the continuation of essential training while preserving the health and welfare of its people.

All crew on Adelaide were screened for COVID-19 symptoms before departure.

At sea, health threats including communicable diseases like COVID-19, are deliberately considered as part of force health protection.

Major Fleet Units deploy with a medical officer or an appropriately trained medical team who are capable of screening and providing care to any personnel with symptoms.

“Adelaide is currently the Navy’s High Readiness Vessel and may be tasked by the Australian Government to respond to emergencies across the region, including support to civil authorities in Australia, or overseas, in their efforts against COVID-19. It is imperative that we maintain that high readiness capability, and provide reassurance that ADF can respond immediately even in times of crisis,” Captain Ley said.

The MH-60R ‘Romeo’ helicopter, based at 816 Squadron in Nowra, New South Wales, is the Navy’s next generation submarine hunter and anti-surface warfare helicopter.

The trials are a crucial testing process to establish the true extent of how the MH-60R operates in the maritime environment on Navy’s various platforms.

Lieutenant Commander Chris Broadbent of the Aircraft Maintenance and Flight Trials Unit said the trials include aviation facilities assessments, equipment calibration, and evaluation of the interface between a particular helicopter type and class of ship.

“While MH-60R aircraft have been used on HMA Ships Adelaide and Canberra for some time, new tests are required to determine what new safe operating limits they can achieve when working together,” Lieutenant Commander Broadbent said.

The flight trials will be conducted in Queensland waters over the coming weeks and include actively chasing the right weather conditions to adequately prove capability.

See the following story about the Indian Navy joining the Seahawk global enterprise:

indian-navy-to-acquire-seahawk-helicopters

The kind of cross-deck flexibility being demonstrated by the RAN’s Romeo helicopters could well affect the way ahead for Army Aviation. If cross-deck flexibility is prioritized, this perspective could well impact the current Army Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter competition.

In this March 6, 2020 article by Mike Yeo published by Defense News, the cross-deck flexibility of the Romeo was highlighted.

The Royal Australian Navy has managed to integrate the Sikorsky MH-60R Seahawk naval helicopter with a range of vessels that were not included in the original plans when Australia decided to acquire the type, according to the deputy commander of the RAN’s Fleet Air Arm.

Speaking to media during a visit at the invitation of simulation provider CAE to the naval base at HMAS Albatross, located in Nowra, south of Australia’s largest city Sydney, Capt. Grant O’Loughlan touted the MH-60R’s capabilities and interoperability with U.S. Navy systems, even as the service retains the autonomy to customize the helicopter for its unique needs.

The additional vessels with which the helo is compatible include the RAN’s support ships and the Canberra-class landing helicopter docks used for amphibious operations. O’Loughlan noted that “the range of missions that this helicopter can undertake is significant.”

The diverse mission sets range from maritime domain awareness, electronic warfare, vertical replenishment, and search and rescue thanks to its extensive onboard suite of networked systems in addition to its primary anti-submarine warfare role.

By Robbin Laird

NATO and the European Union are the two European alliances which provide multi-lateral responses to crises within Europe.

Clearly, a health care driven crisis such as the coronavirus crisis falls largely in the province of the individual European nations and the shared sovereignty which is delegated to the European Union.

NATO’s role in the crisis is more limited, and has largely focused on providing targeted military airlift to supplement civilian resources. With passenger traffic ramped down significantly, civilian airlines are providing enhanced freighter support during the current phase of the Coronavirus crisis. Military airlift can provide a compliment to civilian assets in moving patients or supplies to critical points in the response chain during the crisis.

On April 2, 2020, NATO’s Rapid Air Mobility (RAM) capability was activated by the North Atlantic Council which facilitated the ability to move military airlifters through European airspace.

According to Camille Grand, NATO assistant secretary general for defense investment, “COVID-19 is a different scenario to what we had anticipated [for RAM],” Grand says. “The airspace is not exactly crowded, but on the other hand, there are fewer air traffic controllers than in normal times. So it is not absurd to suggest that military flights should get priority.”

On April 10, 2020, the first COVID-19 flight using RAM was initiated by Turkey in support of the United Kingdom.

According to Tony Osborne of Aviation Week: Although the Turkish A400M carried much-needed medical protective gear destined for the UK’s National Health Service, RAM was originally developed so that NATO members could quickly reinforce their garrisons on the outer edges of the alliance, such as the Baltic States, with personnel and equipment at a time of growing crisis and support the alliance’s Very High-Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF).”1

In an April 16, 2020, virtual town hall meeting moderated by Atlantic Council Executive Vice President Damon Wilson, NATO Deputy Secretary General Mircea Geoană provided an overview of the role of NATO in the crisis.

According to Geoană, NATO defense ministers agreed that “anybody having something in excess—because not all countries are affected the same—[should] use [NATO’s] coordination mechanism and make sure that the ones who have the most need and the places with the most urgent need receive [support.]”

He noted that the first reaction of many governments to the pandemic was naturally “to take care in the best possible way of their own citizenry,” but argued that “after the first shock, we started to realize that this is something you cannot fight alone…we need each other.”

“We have not been perfect,” he argued, “but I think after the initial instinct of [focusing] on our own [countries], we see now from the United States all the way to North Macedonia…a renewed sense of solidarity and I think we will be coming out stronger from this crisis.”

The pandemic has also demonstrated NATO’s continued value in facilitating the cooperation between allies that is so vital during crises, Geoană said. “Our DNA is crisis management, our DNA is command and control, our DNA is efficiency and logistics and putting together in critical moments the pieces that can make a nation and an alliance in distress work,” he explained.

Geoană argued. “NATO is equipped in the way we function, the way we take decisions, the agility and the vigilance that is in built into our [organization] to adjust.”

“We do not want for anyone to believe that for one second that because of this pandemic that the Alliance is less vigilant and less able to protect and defend our citizens,” Geoană maintained.

Continued readiness is important, he added, because “the threats and concerns to our common security have not gone away because of the pandemic, in a way they have been amplified.” He noted that NATO officials have observed “Russia doing some snap exercises under the pretext of the pandemic” and threats from non-state actors to try to take advantage of distracted political leaders to hit against NATO interests. NATO’s primary mission right now, he said, is “preventing…a global health crisis from becoming a security crisis.” At such an important time, he explained, “we just cannot lower our vigilance because there is a moment of great difficulty.”

He highlighted the challenge of information war as well. “The pretext of the pandemic is being used and abused by state and nonstate actors in a massive infodemic,” he said, as they are promoting “disinformation [and] conspiracy theories, [and] putting seeds of discontent and mistrust” online.

Geoană said that NATO officials continue to work with the EU and other national governments to push back on these false narratives, arguing that leaders “have to mythbusters ourselves” as “this is something we can only fight with the truth.”

Geoană also warned that NATO’s authoritarian rivals could use the economic damage dealt by the pandemic as an opportunity to “try to abuse our relative weakness and purchase strategic industries and infrastructure.”

He said NATO would be paying specific attention to protecting vital infrastructure and industries which could be sold off to competitors as an easy way to raise funds in what could be a difficult road to recovery for many allies. Geoană also cautioned against suggestions that the economic crisis should trigger cuts to defense spending as “our security is as much needed and investment in our security is as much needed as before—perhaps even more.”

NATO leaders are also already planning for a world after COVID-19, according to Geoană. Alliance officials had previously created resilience standards for member states for crises—such as continuity of business for governments, protection of infrastructure, and access to vital resources—which have now experienced the ultimate stress test. The deputy secretary general said NATO defense ministers were already beginning to “update” these standards and have begun to “integrate the lessons” of the crisis into future plans.

“Our main business is to keep 1 billion people safe,” from security threats but also in every way NATO can from other emergencies like the coronavirus pandemic, Geoană stressed. As allies continue to reach out with assistance and coordination through this crisis, he said, it is no wonder why “solidarity is a key word in our alliance.”2

There has also been European cooperation among NATO states via military airlift as well. In a story by Pierre Tran published on March 29, 2020, he highlighted Franco-German cooperation during the crisis.

“The French army has flown coronavirus patients to Germany in an NH90 Caïman helicopter, while a German A400M military transport plane flew patients out of France, signaling close bilateral ties, the armed forces ministry said March 29.

“The French and German armed forces are working together to fight against Covid-19,” the ministry said in a statement. “This cooperation shows the solidarity of the Franco-German friendship.”

“Armed forces minister Florence Parly spoke March 27 to her German counterpart, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, on the virus crisis and the two ministers agreed on measures to help hospitals in northeastern France, the ministry said.

“The French army flew March 28 an NH90 military transport helicopter carrying two patients out of Metz, northeastern France, to a hospital in Essen, western Germany, the ministry said. French civil emergency services helped that flight.

“That flight was part of Operation Resilience, a broad military mission seeking to lighten the load on civil authorities across France, heavily hit by the pandemic…..

“The German air force sent an A400M airlifter to Strasbourg, northeast France, to fly French patients to a German hospital, Parly said over social media. “Just one word: thanks,” she said.

“That was the first German military flight of French patients, regional paper L’Alsace reported. The operation took just under two hours to embark the patients before flying to Stuttgart. The patients were then taken to the military hospital in Ulm, southwest Germany, AFP news agency reported, the paper said. The German A400M flying hospital also took virus patients from Bergamo, northern Italy, to help medical staff in the Lombardy region, suffering heavily from the virus. The patients were flown to Cologne, western Germany.

“Germany made its A400M airlifter available through European Air Transport Command, which comprises seven member nations: Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Spain and the Netherlands.”3

The crisis is precisely that and highlights the importance of working crisis management skills which have largely atrophied in the period of the land wars.

As Derek Chollet has argued: “This crisis must also jumpstart NATO discussions around crisis decision making. NATO’s ability to make decisions quickly has been an enduring challenge. Yet the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 crisis is forcing the alliance to adapt on the fly and work from home. The ability to deliberate remotely by secure videoconference, which NATO foreign ministers first did last week, demonstrates it’s possible. Improving the speed and accessibility of secure decision-making will bolster deterrence and enhance NATO’s ability to respond to the next crisis.”4

And what follows is the Press conference by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg following the virtual meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Defence Ministers’ session (15 Apr. 2020).

NATO Defence Ministers have just addressed in an extraordinary meeting about the COVID-19 crisis NATO’s response. We have done so by secure video conference.

This was a timely and substantive discussion.

We reviewed our response to the pandemic. And we agreed on the next steps we need to take.

To continue to support each other, and support our partners.

COVID-19 represents an unprecedented challenge to our nations.

It has a profound impact on our people and our economies.

And it is imposing historic shocks on the international system, which could have long-term consequences.

The crisis has shown that our nations are resilient, and united.

Our militaries are already playing a key role in support of national civilian efforts.

And using NATO mechanisms, Allies have been helping each other to save lives.

NATOs top operational commander, General Wolters, was tasked by foreign ministers two weeks ago to coordinate military support.

And today he updated us on his efforts to ensure NATO uses its military resources most effectively.

Today, I encouraged all Allies to make their capabilities available so General Wolters can coordinate further support.

And I welcome the additional offers made by ministers today.

All NATO Allies are affected by the pandemic.

But not in the same way at the same time.

So when we effectively coordinate our resources, we make a real difference.

Defence ministers also addressed NATO’s continued deterrence and defence.

The bottom line is that security challenges have not diminished because of COVID-19.

On the contrary.

Potential adversaries will look to exploit the situation to further their own interests.

Terrorist groups could be emboldened.

The security situation in Afghanistan and Iraq remains fragile.

And we see a continued pace of Russian military activity.

So we must maintain our deterrence and defence.

Because our core mission remains the same: to ensure peace and stability.

While we continue to take all the necessary measures to protect our armed forces, our operational readiness remains undiminished.

And our forces remain ready, vigilant and prepared to respond to any threat.

***

We also discussed the importance of countering disinformation: Both from state and non-state actors.

Trying to sow division in the Alliance and in Europe.

And to undermine our democracies.

We are countering these false narratives with facts, and with concrete actions.

We are also working even closer with Allies, and the European Union, to identify, monitor, and expose disinformation.

And to respond robustly.

***

Finally, we considered the long-term implications of this health crisis.

For our societies, and for the world around us.

The geo-political effects of the pandemic could be significant.

Some may seek to use the economic downturn as an opening to invest in our critical industries and infrastructure.

Which in turn may affect our long-term security.

And our ability to deal with the next crisis, when it comes.

So ministers had an in-depth discussion on how we prepare for the long-term effects of COVID-19.

It is too soon to draw the final conclusions.

Ministers agreed a set of recommendations to strengthen our resilience.

Because COVID-19 is a threat to all of us.

And together, we can emerge stronger from this unprecedented crisis.

The featured Photo: MADRID, SPAIN- In the photos, members of the Spanish Air Force unload aid supplies from the Czech Republic, in Madrid, Spain on March 29, 2020. A C-130 cargo plane from the Spanish Air Force that transports 10,000 protective medical suits donated by the Czech Republic land at Torrejon Air Base, Spain as part of allied efforts to combat the effects of the coronavirus pandemic. (via REUTERS)

By Pierre Tran

Paris – Armed forces minister Florence Parly denied April 17 media reports the captain of the Charles de Gaulle had asked for an early return to base to limit the spread of coronavirus on board the aircraft carrier.

“It has been said the captain wanted to break off the carrier task force mission at the stop over at Brest,” she said in a video meeting with the defense committee of the lower house National Assembly.

“This rumor is false,” she said. “The captain has, himself, confirmed that and the navy spokesman clearly denied that yesterday.”

The minister delivered her public rebuttal following a report from France Bleu local radio which said the captain had asked to sail the carrier back to the Toulon home base due to concern over Covid 19, and the ministry had rejected that request.

France Bleu had reported an account given by a sailor who had been on the carrier and had contracted the coronavirus.

Tests for coronavirus showed 1,081 sailors had contracted the infection, with 545 sailors showing symptoms and kept under close medical supervision, Parly said.

Twenty four sailors have been admitted to a Toulon military hospital, with one in intensive care, she said.

“Our thoughts are particularly with them,” she said.

There were 1,760 sailors and personnel on board when the Charles de Gaulle sailed January 21 out of Toulon.

The carrier had been at the dockside March 13-16 at Brest naval base and had visited Cyprus in February, Parly said. The navy had approved the stop over for reasons of logistics and well being of the crew, who had worked hard.

That stop over at Brest took place before the national lock down went into effect, she said. It is not known whether the virus was already on board before the visit to Brest.

“Could the captain measure the shadow of the pandemic at that time?” she said.

“Command is difficult,” she said. Knowledge of the virus was more limited then compared to what is known today, she added.

France entered the lock down at midday March 17, with the strict conditions of national confinement extended to May 11.

After leaving Brest, the carrier task force went on to sail in allied exercises in the North Atlantic and the North sea, before curtailing the mission and returning to Toulon on April 12. Some sailors had shown signs they might have caught the infection, prompting emergency medical tests April 8 on board the carrier.

The tests showed 50 sailors had caught the virus, prompting a recall of the carrier task force, which included two frigates and a fleet auxiliary tanker.

There are now two enquiries on what happened on the carrier, with a medical team looking to trace how the coronavirus got on board and a command enquiry to learn lessons on how the officers managed the situation once the virus had hit the crew.

Some 30 percent of the warships in the carrier task force have been cleaned, Parly said. The carrier had previously been due to return April 24.

See also the following:

By Pierre Tran

Paris – Around a third of the sailors on the Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier have shown infection by coronavirus, with one sailor placed under intensive care in a Toulon military hospital, the armed forces ministry said April 15 in a statement.

The navy chief of staff, admiral Christophe Prazuck, has launched a formal enquiry into how the spread of the pandemic on the carrier was managed.

“By the evening of April 14, 1,767 sailors of the carrier strike group have been tested,” the ministry said. “Six hundred and sixty eight have shown to be positive.”

The vast majority of tests for Covid 19 so far conducted were on sailors of the carrier, with 30 percent of the tests yet to be examined, the ministry said. Thirty one sailors have been admitted to military hospital in Toulon, southern France, with one of those receiving intensive care.

The tests are continuing.

Some 1,700 sailors and personnel sailed on board the Charles de Gaulle capital ship and some 200 sailors on the frigate escort, Chevalier Paul, on the operation Foch.

Almost 600 sailors who sailed the US carrier Theodore Roosevelt have been hit by the virus, and one sailor has died. The infection spread through the crew while the carrier was at sea in the Pacific, and the then captain had sought an early return.

The formal command enquiry ordered by Prazuck, a former navy chief press officer, may address strong feeling reported to be felt among sailors, who are in a 14-day quarantine at Toulon naval base and in bases in nearby Saint-Mandrier and Hyères.

A sailor who had been on board the carrier said he was “angry,” France Bleu local radio reported from Toulon. “The services played with our health, our life.”

The captain of the Charles de Gaulle had asked for an early return to base when the carrier docked at Brest, northwest France, said the sailor, infected by the virus.

There were already sailors showing signs of the virus and the captain wanted to place the crew into isolation immediately, the sailor said. The ministry declined the captain’s request, the sailor said.

The navy chief of staff has ordered a command enquiry to learn all the lessons on management of the epidemic in the air-naval group, the ministry said. That included the conditions for the virus on board the aircraft carrier, a ministry spokesman said.

The enquiry will take several weeks, France Bleu reported.

There were no Covid 19 symptoms reported to the medical service when the carrier was at Brest, said a senior naval doctor, Ouest France regional paper reported. The carrier docked into the naval base in northwest France mid March.

The command on the carrier was overtaken by events, with two sailors showing signs of the virus without being put into confinement, Mediapart website reported.

The Charles de Gaulles is not just a warship capable of strategic missions but a highly political statement, the pride of the French services in which show of force is a communications tool, Mediapart said.

Pilots who flew the carrier-borne Hawkeye airborne warning and control system platform, Rafale fighter jets and helicopters are going through 14-day quarantine on their own bases, the ministry said.

At Brest naval base, tests on the crew of the anti-submarine frigate La Motte Picquet have come up negative, allowing the sailors to go into confinement at home, the ministry said.

Tests on the crew of the fleet auxiliary tanker, Somme, have led to some 60 sailors held in strict isolation at the base as a precautionary measure, while some 100 sailors have gone home for quarantine.

The navy is cleaning warships and aircraft, drawing on joint military and civilian teams.

The Charles de Gaulle was the flagship of operation Foch, which had been due to sail for three months, with the carrier task force previously planned to return April 23 to Toulon after sailing out January 21.

The operation had sailed in the eastern Mediterranean and the North Sea, and reportedly docked at Brest March 13-16.

A command enquiry is a formal internal or administrative investigation which seeks to identify a dysfunction or risk which might change the functioning of organizations or services, according to the official journal.

France has recorded 17,167 deaths due to coronavirus, with 10,643 dying in hospital and 6,524 in care homes, afternoon daily Le Monde reported April 16.

That excludes those who died at home.

More than two million people around the world have been confirmed as suffering from Covid 19, breaking a highly symbolic threshold, according to John Hopkins university.

Some 138,487 have died, while 528,300 have recovered.

A key aspect of how the Royal Australian Navy is working integration across the fleet and shaping a way ahead for the ADF as an integrated distributed combat force is shaping commonality across its combat systems.

As Vice Admiral (Retired) Tim Barrett has highlighted about the approach:

“We see new shipyard capabilities and new industrial partnerships being forged to build a new approach to shipbuilding.

“It is being done with a new approach which is not just focusing on a traditional prime contractor method of building the hull and having the systems targeting that specific platform.

“It is about building a sovereign capability for our combat systems so that we can upgrade our systems onboard this class and all future classes of Australian ships.”

Clearly, this a key emphasis with regard to the new build submarine where Naval Group is leading the design and build effort, and Lockheed Martin and its team are working the combat systems effort.

A recent article by Max Blenkin published in ADBR in their November-December 2019 highlight the approach being taken in this program.

Submarines – like any warship – only exist to keep their electronics, weapons and crew dry, and to get them where they need to be. That’s not at all well-appreciated in the ongoing public discussion around Australia’s 12 new Project SEA 1000 Attack class submarines and their design by prime, France’s Naval Group.

Proceeding steadily but with less public commentary is the combat system design, development and integration by Lockheed Martin Australia. The combat system accounts for a significant portion of the overall project – the basic rule of thumb is that the combat system in a modern warship accounts for around 20 per cent of total project cost.

Considering the future submarines project has been costed around $50 billion, that places the combat system component at about $10 billion. This work is proceeding at a steady pace.

In October the combat system development review was completed, with the next major combat system milestone the preliminary design review (PDR) in the second half of 2021, followed by the critical design review (CDR) in the first half of 2023.

Mike Oliver, Lockheed Martin’s program director for the submarines’ combat system, said this system would be state-of the-art, and will be a step on from the combat system aboard the Navy’s six Collins class subs which employ a version of the US Navy AN/BYG-1.

“This boat will be operational out to the 2070s,” Oliver told ADBR. “It’s important that we understand that boat one will not be the same as boat 12.

“What we have to achieve is flexibility in our design so we can accommodate those new technologies as they come along, so we can keep the functionality of the combat system,” he added. “We call it pacing the threat, keeping in front of the adversary.”

Oliver said the proposed system would feature some basic functionality which would be pretty identical to what was aboard just about any submarine in the world today.

“What really makes the combat system unique are the sensors we are putting on the boat and the amount of data and information coming from those sensors,” he said. “That’s where you start seeing this big improvement on contemporary boats of the day. It is just taking advantage of the technology.

“The processing power is getting more and more every year and how we take advantage of that to actually process more of the data and present that to the operator.”

In simple terms, the combat system links the submarine sensors – bow, flank and towed array sonars – with the weapon system, the Mark 48 torpedoes, and maybe eventually submarine-launched missiles. Information is presented to operators in the submarine control room, where the commander can then make the appropriate decisions.

The Navy had big ambitions for the Collins combat system, but the then available technology was barely up to the task and integration proved difficult, protracted and costly.

Of all the many problems afflicting the Collins boats in the early years, the combat system was the most intractable. It was only fully remediated with the decision to go to AN/BYG-1, installed first aboard HMAS Waller in 2008. That was 15 years after the launch of HMAS Collins.

The Attack class’s combat system will be mostly fully developed and proven long before it’s actually installed on a submarine.

“I anticipate starting what I will call pre-production and prototype development in the 2022-23 timeframe and our strategy and aim is to evolve the combat system and get that early so I can work to find the problems and issues through the lab-based integration before I deliver it to the shipyard to be integrated,” Oliver said.

“The timeline to deliver to the shipyard is in 2028. That’s delivery and integration into the platform. Platform integration will be a little bit beyond that before the boat actually hits the water.”

The Attack class combat system will be based on the AN/BYG-1, but will feature enhancements through improved technology plus additional capabilities. It is being designed with full open architecture to accommodate emerging technologies such as unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs).

“We are designing the combat system to accommodate whenever those become available,” Oliver said. “There is a lot of research and development being done by a lot of the navies of the world on how they want to use unmanned submersibles and unmanned aircraft. We have designed the combat system architecture to accommodate when that capability comes along.”

The design team is also looking to integrate automation of some systems, where appropriate. Oliver said there were some ship functions which could be automated. “There are some things, because they involve ship safety or ability to protect that ship, where you always want a human in the loop,” he said.

One consideration not yet finalised is how many crew members will an Attack-class boat need? A Collins boat’s complement is 45.

“It’s not just the ability to man the consoles and the attack centre, but you have to look at the total ship – damage control and all these sorts of things, what’s the number you need,” Oliver said.

John Towers, Lockheed Martin’s lead for submarine combat system human integration added, “There is a lot of work being done now in terms of the complement. To understand what are the tasks and how we effectively design roles for the future submarine, that is an ongoing effort.”

Unlike Collins, Attack class boats will be fitted with an optronic mast with day/night vision capability in place of the traditional optical periscope. This has a significant advantage for submarine design in that it doesn’t penetrate the pressure hull, and frees up interior space.

It also provides additional inputs to the combat system from the mast’s high definition cameras. An optronic mast also supports antennae for communications and electronic surveillance.

Oliver said in the combat system design, they were aiming for complete separation from the hull design. “We know the combat system will continue to evolve. I want to be able to evolve and upgrade that combat system relatively quickly without impacting ship design.

“We are smarter in those interfaces. When I do an evolution of the combat system, it doesn’t impact the ship as long as I stay within my margins,” he added. “We have a vision to be able to upgrade and update the combat system pier-side so it doesn’t have to go into mid-cycle or full cycle docking.”

However Lockheed Martin and Naval Group will still need to work together in the design process to make everything fit. “As Naval Group is progressing their design they need to know attachment points, cable runs and all those sorts of things so they can design the boat to accommodate that,” Oliver said.

“The challenge is making sure as I deliver the interface control drawings that they are correctly interpreted by Naval Group. That is one of the reasons I have a small team in Cherbourg.”

That starts at gross conceptual level and eventually moves to 100 per cent accuracy. Initially the combat system team specified basic space, weight and power requirements to allow Naval Group to do what they term their balances. “We have all those information exchange touch points with Naval Group, well defined on when we owe them data and they owe me data,” Oliver said.

The control room is the beating heart of any submarine, traditionally located beneath the conning tower so the commander can readily access the periscope. Operators stare intently at consoles displaying graphic coloured representation of signals from the sonar sensors.

But using an optronic mast means the control room need not be located directly beneath the conning tower. On USN Virginia class nuclear attack boats, the control room has been moved one floor down, providing substantially more space.

Designing the combat system and the control room to provide operators and the commander with the most useful and timely information is a key task of the development process.

John Towers said their objective was to ensure the combat system allowed operators to perform at optimum level. That applies to all aspects involving the operators – from physical design of combat system elements through to the cognitive effort they have to apply to any particular task.

“We are responsible for ensuring that is not excessive and they have the right information at the right time in the right format to perform the tasks we are expecting them to,” he said.

“It really involved in the first instance establishing a baseline of understanding for which existing doctrine and workflow on the submarines they (the Navy) definitely don’t want to change, what works well.”

There’s actually a well-established engineering methodology for human factors on the program. “We have done sea rides, we observe training, interviewed submariners,” Towers said. “What that helps us do is get a starting point and a baseline to establish early task models.

“We develop high level scenarios and then the underlying work flow of tasks and roles and role interactions, heavily leveraging in the first instance off Collins. It is going to evolve with new functions and optimisation of operations.

“Then we move into simulation of those models,” he added. “We use a commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) simulation tool. We have invested heavily in human system integration on the program to the point where we have a really well-established best practice for these activities, and it has given us an opportunity to really leverage that and start developing some of our own tools that take it to the next level.”

Then it moves on to physical design. Right now that involves some cardboard mockups of workstations to assess lines of sight. “Then we are building a very representative combat system simulator,” Towers said.

“As part of that we will start getting submariners into the lab and having them dynamically work with the combat system and we will extract performance measures of how well they are doing, how well our mitigation strategies work for issues we perhaps find in the modelling.”

Towers said all through this process, they were working closely with the Navy. “They are gaining an insight into what we are thinking, how we are interpreting results, what’s accurate and what they believe is maybe a bit off track for one reason or another,” he said.

Oliver, a former USN submariner, said in the past each control room operator had a particular role. “My job was just to look at the data coming from a particular sensor. That’s all I did. I had somebody else working other sensors. Nobody had the ability to integrate that full situational awareness picture seamlessly.

“Today it’s not so much role-based – looking at the towed array or the flank array or the bow array,” he added. “You are just looking at the data. You don’t really care where the data is coming from. You can find it if you want but it is presenting that as a total picture.

“The systems now integrate that data to present you with a different picture. You still have the ability to drill in to see the data if you want to. But you find out if you do that you start getting tunnel vision. That’s not just sonar – it’s all of the sensors.”

Lockheed Martin is also looking to industry and academia for ideas, offering research grants for particular research projects in search of capabilities of the future.

“They will give us the results of their research paper and we will analyse and assess those and, if it merits further research, we will fund them up to an additional million dollars to mature that capability,” Oliver said.

“We go through that annually and the idea is that we keep this flow of new ideas in this pipeline. Some things will come out the end and go into the system as the technology is available.

“Some things may not be quite ready, and we may keep it in the pipeline a little bit longer. The idea is to build the capability and capacity in Australia.”

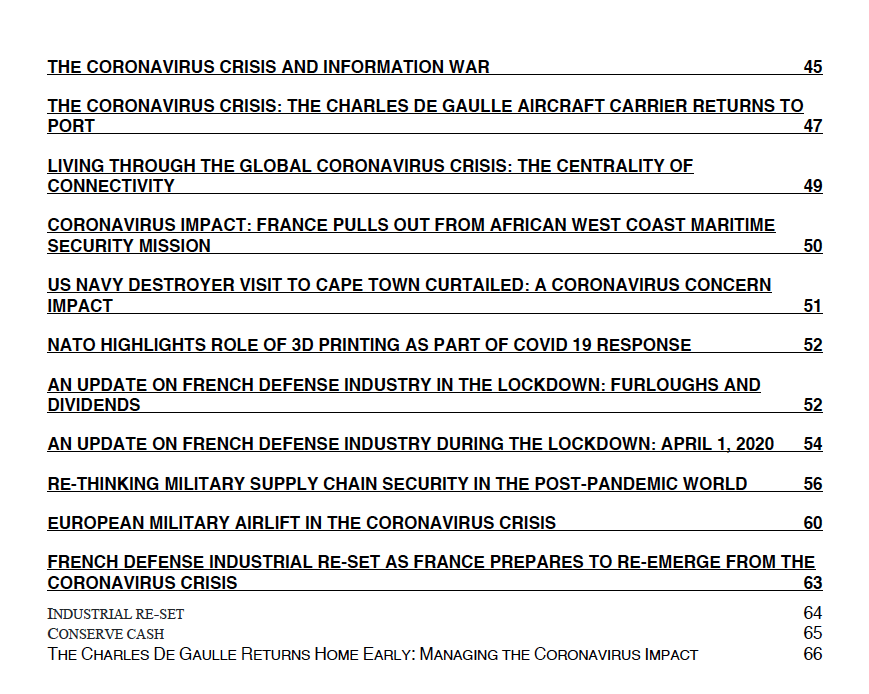

This special report brings together in one publication our recent pieces published on Second Line of Defense and Defense.info, since the coronavirus crisis became a significant crisis management challenge.

We cover a number of topics, indicated in the Table of Contents for the Report:

For the PDF version of the report, please see the following:

The Coronavirus Crisis: Perspectives and Shaping a Way Ahead

For the e-book version of the report, please see the following: