By Robbin Laird

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit with Rear Admiral Pete Garvin in his office in Norfolk Virginia to discuss the way ahead with the US Navy’s Patrol and Reconnaissance Force (MPRF).

Commander Patrol and Reconnaissance Group / Commander Patrol and Reconnaissance Group Pacific (CPRG/CPRG-PAC) provides oversight to more than 7,000 men and women on both coasts operating the U.S. Navy’s maritime patrol aircraft including the P-8A “Poseidon”, P-3C “Orion”, EP-3 “Aries II” and MQ-4C “Triton” unmanned aircraft system.

The MPRF is organized into two Patrol and Reconnaissance Wings at NAS Jacksonville, Florida, and NAS Whidbey Island, Washington including 14 Patrol and Reconnaissance squadrons, one Fleet Replacement Squadron (FRS) and over 45 subordinate commands. The MPRF is the Navy’s premier provider for airborne Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW), Anti-Surface Warfare (ASuW), and maritime Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) operations.

We discussed the force transformation currently underway as the foundation for further innovation moving into the future for the maritime force in its global operations. The P-8A and MQ-4C are not simply replacement platforms for the P-3 and EP-3. The change is as dramatic as the Marines going from the CH-46 to an Osprey which could only be described as a process of transformation rather than a transition from older to newer platforms.

It is not simply that these are different platforms, but the question of how to title the article suggests the dynamics of change. These are not merely maritime patrol aircraft but rather a synergistic ‘Family of Systems’ empowering global maritime domain awareness and the joint strike enterprise.

Most importantly, while the P-8A is a capable engagement platform in its own right, the information generated by the P-8A/MQ-4C dyad empowers and enhances the organic ASW strike capability on the P-8.

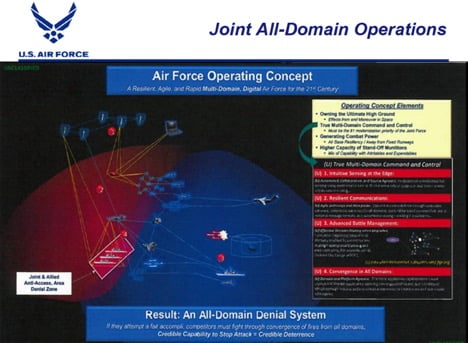

Moreover, the entirety of Department of Defenses’ strike capability is enhanced against adversarial multi-domain forces.

We hear a lot about the coming of Artificial Intelligence and new sensors to the combat force, but the P-8A and MQ-4C are bringing these capabilities to the force today. With pre-mission planning and post-mission product dissemination supported by a dedicated “TacMobile” ground element, these platforms comprise a solid foundation for the new MDA enterprise. Working together, the weapon systems will deliver decisive information to the right place at the right time to empower the multi-domain combat force. These systems are designed to be quickly software upgradeable and evolve over time as combat performance, and contact with the adversary, provide significant real-world feedback.

Although these are US Naval platforms, they are designed to connect with the larger C2/ISR infrastructure, changing the capabilities and operations of the entire U.S. and allied combat forces.

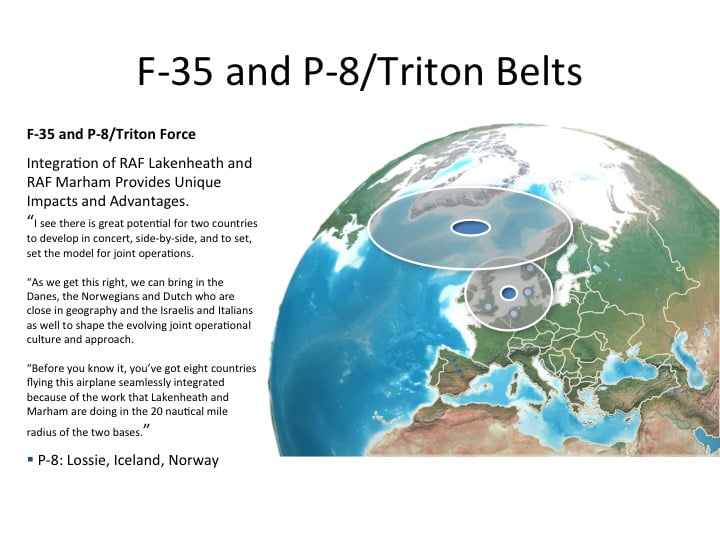

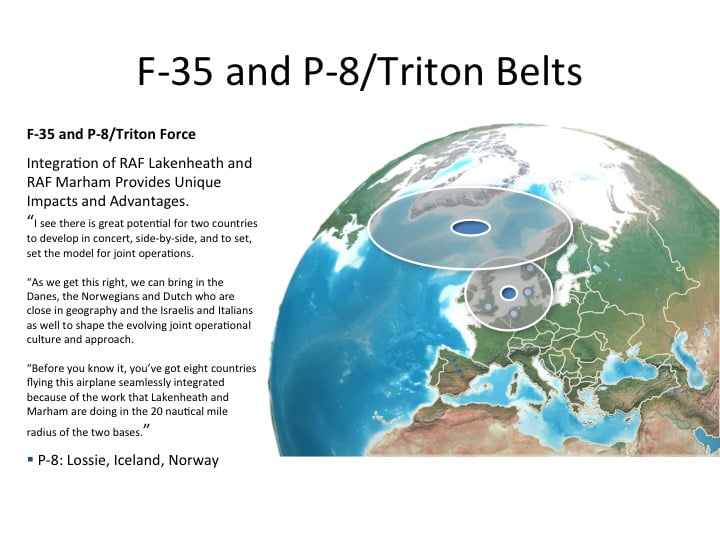

With core allies buying P-8 and MQ-4C, this force is truly global.

My visits to Norway, the United Kingdom, and Australia have provided significant opportunities to discuss with those nations, how they are engaged with the United States in recrafting the MDA and strike enterprise.

These platforms provide significant situational awareness for a task force, and can operate in effect as combat clouds for a tailored task force operating across the spectrum of conflict.

At the recent International Fighter Conference 2019, there was significant discussion of the coming of manned and unmanned teaming. There were no naval aviators at the conference but if they had been present, they would have told the conference that the U.S. Navy is already working and improving manned/unmanned teaming concepts and doctrine.

With the coming of Triton, a completely new approach is being shaped on how to operate, and leverage the data and systems onboard the manned and unmanned air systems joined at the hip, namely, the P-8 and the Triton.

There is an obvious return to the anti-submarine mission by the U.S. and allied navies with the growing capabilities of the 21st century authoritarian powers.

However, as adversary submarines evolve, and their impact on warfare becomes even more pronounced, ASW can no longer be considered as a narrow warfighting specialty.

This is reflected in Rear Admiral Garvin’s virtuous circle with regard to what he expects from his command, namely, professionalism, agility and lethality.

The professionalism which defines and underpins the force is, in part, about driving the force in new innovative directions. To think and operate differently in the face of an evolving threat. Operational and tactical agility is critical to ensure that the force can deliver the significant combat effect expected from a 21st century maritime reconnaissance and strike force. Finally, it is necessary but insufficient to be able to find and fix an adversary.

The ability to finish must be realized lest we resign ourselves to be mere observers of a problem.

The Australians consider the P-8/Triton force to be part of their fifth-generation transition in that the information being processed and worked by the machines in the dyad and the analysts onboard or ashore is informing assets across the enterprise with regard to threats and resolutions required by the entire combat force.

It is not simply about organic capabilities.

The P-3 flew alone and unafraid; the dyad is flying as part of a wider networked enterprise, and one which can be tailored to a threat, or an area of interest, and can operate as a combat cloud empowering a tailored force designed to achieve the desired combat effects.

The information generated by the ‘Family of Systems’ can be used with the gray zone forces such as the USCG cutters or the new Australian Offshore Patrol Vessels. The P-8/Triton dyad is a key enabler of full spectrum crisis management operations, which require the kind of force transformation which the P-8/Triton is a key part of delivering the U.S. and core allies.

A key consideration is the growing importance of what one might call “proactive ISR.”

It is crucial to study the operational environment and to map anomalies; this provides a powerful baseline from which to prepare future operations, which require force packages that can deliver the desired kinetic or non-kinetic effect.

Moreover, an unambiguous understanding of the environment, including pattern of life and timely recognition of changes in those patterns, serves to inform decision makers earlier and perhaps seek solutions short of kinetic.

This is not about collecting more data for the intelligence community back in the United States; it is about generating operational domain knowledge that can be leveraged rapidly in a crisis and to shape the kind of C2 capabilities which are required in combat at the speed of light.

Historically, a presence force is about what is organically included within that presence force; today we are looking at combat reach or scalability of force.

Faced with limited resources, it is necessary for planners to exercise economy of force by tailoring distributed forces to a specific area of interest for as long as required.

The presence force however small needs to be integrated not just in terms of itself but also in its ability to operate via common C2 or ISR connectors with both allied and U.S. forces. This enhanced capability needs to be forward deployed in order to provide enhanced MDA, lethality and effectiveness appropriate to achieve the desired political/military outcome.

Success rests on a significant rework of C2 networks to allow a distributed force the flexibility to operate not just within a limited geographical area, but reach beyond the geographical boundaries of what the organic presence force is capable of doing by itself.

This is about shaping force domain knowledge well in advance of and in anticipation of events.

This is not classic deterrence – it is pre-crisis and crisis engagement.

This new approach can be expressed in terms of a kill web, that is a U.S. and allied force so scalable and responsive that if an ally executes a presence mission and is threatened by a ramp up of force from a Russia or China, that that presence force can reach back to relevant allies as well as their own force structure in a timely and effective manner.

For this approach to work, there is a clear need for a different kind of C2 and ISR infrastructure to enable the shift in concepts of operations. Indeed, when describing C2 and ISR or various mutations like C4ISR, the early notions of C2 and ISR seen in both air-land battle and in joint support to the land wars, tend to be extended into the discussions of the C2 and ISR infrastructure for the kill web or for force building of the integrated distributed force.

The P-8/Triton dyad lays a solid foundation for the wide range of innovations we can expect as the integrated distributed force evolves: expanded use of artificial intelligence, acceleration of the speed for software upgradeability, achieving transient combat advantage from more rapid rewriting of software code, an enhanced ability to leverage the weapons enterprise operating from a wide variety of air, ground, and naval platforms (off-boarding), and an ability to expand the capabilities of manned-unmanned teaming as autonomous maritime systems become key elements of the maritime force in the years to come.

In short, the Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Force is not simply transitioning, it is transforming.

It is delivering significant new capabilities now, and laying a solid foundation for the future. It is empowering what the Aussies would call a fifth-generation multi-domain combat force.

You can either live in the past and lose ground; or you can lean forward and build out the foundation for the integrated distributed force.

Rear Admiral Peter Garvin Biography

Rear Adm. Pete Garvin graduated with merit from the United States Naval Academy in 1989 with a Bachelor of Science in Aerospace Engineering (Astronautics). He is also a 2005 graduate of the National War College, with a Master of Science in National Security Strategy and a 2015 alumnus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Seminar XXI.

His operational assignments include service with the “Pelicans” of Patrol Squadron (VP) 45, where he was the 1995 Association of Naval Aviation Pilot of the Year; department head with the “Mad Foxes” of VP-5; navigator aboard USS Kearsarge (LHD 3), where he served as flag navigator for the embarked Amphibious Squadron (PHIBRON) 6; executive and 59th commanding officer of the “Fighting Tigers” of VP-8; and commander of Patrol and Reconnaissance Wing (CPRW) 10.

His shore assignments include flag lieutenant to Commander, Patrol Wings Atlantic (CPWL), Commander, Task Force (CTF) 84; instructor pilot at the P-3 fleet replacement squadron, VP-30; Washington placement officer at the Bureau of Naval Personnel (PERS 441); executive officer for the director, Operational Plans and Joint Force Development Directorate (J-7), Joint Staff; federal executive fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR); undersea warfare branch head in the assessments division (N81) and deputy director, unmanned warfare systems (N99) on the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations staff; and executive assistant to the vice chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Most recently, he served as the 22nd commander of Navy Recruiting Command. Garvin assumed the duties of Commander, Patrol and Reconnaissance Group July 23, 2018.

His decorations include the Defense Superior Service Medal, Legion of Merit (three awards), Defense Meritorious Service Medal, Meritorious Service Medal (two awards), Air Medal (two strike/flight) and various personal, unit and campaign decorations.

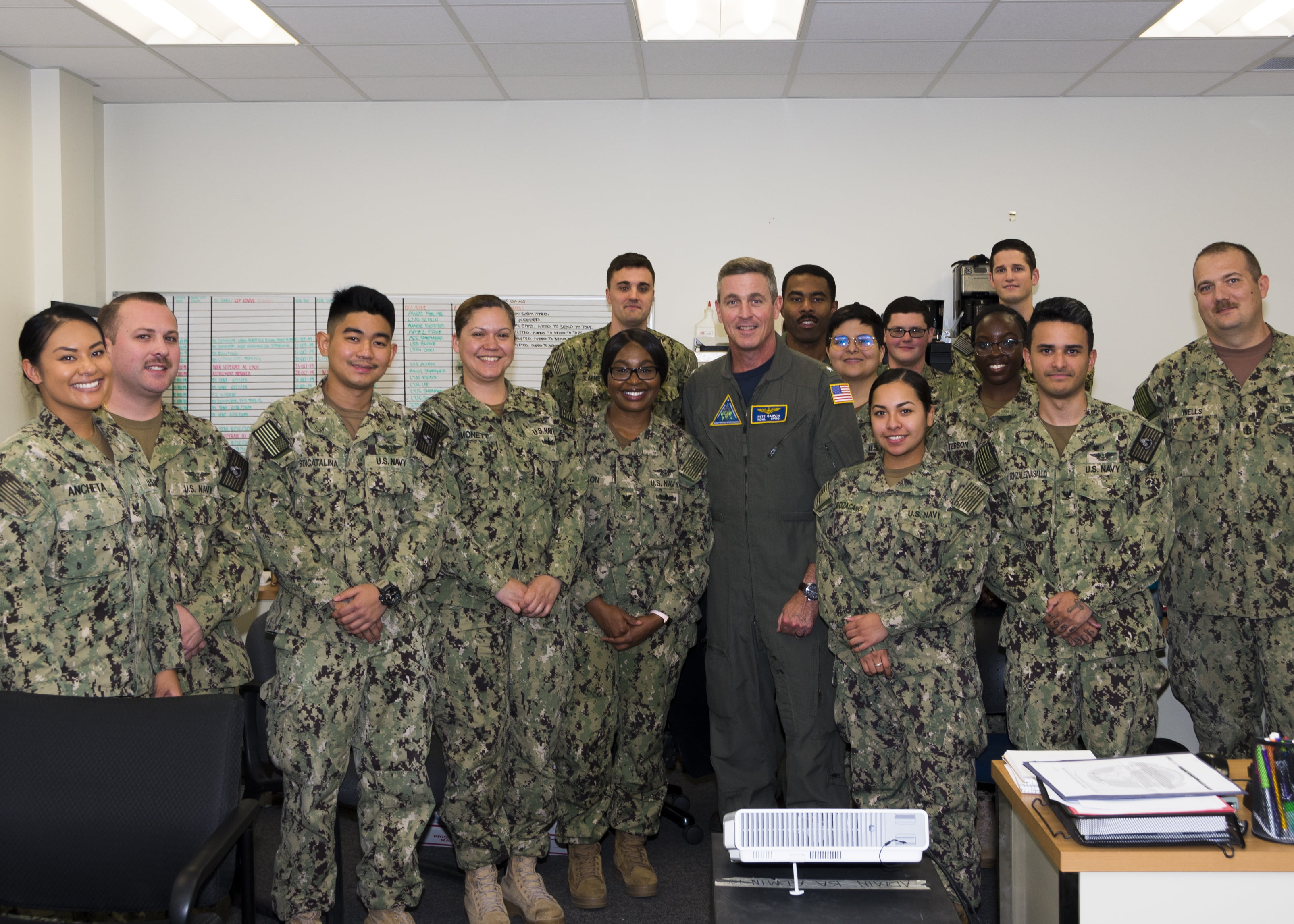

The featured photo shows Rear Adm. Peter Garvin, commander, Patrol Reconnaissance Group, posing for a picture with Sailors of the Patrol Squadron (VP) 46 administration department during a tour of the squadron’s spaces.

VP-46 has recently returned from deployment in the U.S. 5th Fleet and U.S. 7th Fleet areas of operations and is making preparations to transition from the P-3C platform to the P-8A Poseidon.

(U.S. Navy photo by Naval Aircrewman (Operator) 3rd Class Victoria Ruzzo /Released)

OAK HARBOR, Wash. (Oct. 17, 2019)

2016 Visit to Jacksonville Naval Air Station

07/11/2016

On May 23 and 24, 2016, during a Jacksonville Naval Air Station visit, we spent time with the P-8 and Triton community which is shaping a common culture guiding the transformation of the ASW and ISR side of Naval Air. The acquisition term for the effort is a “family of systems” whereby the P-3 is being “replaced” by the P-8 and the Triton Remotely Piloted Aircraft.

But clearly the combined capability is a replacement of the P-3 in only one sense – executing the anti-submarine warfare function. But the additional ISR and C2 enterprise being put in place to operate the combined P-8 and Triton capability is a much broader capability than the classic P-3. Much like the Osprey transformed the USMC prior to flying the F-35, the P-8/Triton team is doing the same for the US Navy prior to incorporating the F-35 within the carrier air wing.

In addition to the Wing Commander and his Deputy Commander, who were vey generous with their time and sharing of important insights, we had the opportunity to interviews with various members of the VP-16 P-8 squadron from CO and XO to Pilots, NFOs and Air Crew members, along with the wing weapons and training officer, the Triton FIT team, and key members of the Integrated Training Center. Those interviews will be published over the next few weeks.

The P-8/Triton capability is part of what we have described as 21st century air combat systems: software upgradeable, fleet deployed, currently with a multinational coalition emerging peer partnership. Already the Indians, the Aussies and the British are or will be flying the P-8s and all are in discussions to build commonality from the stand-up of the P-8 Forward.

Software upgradeability provides for a lifetime of combat learning to be reflected in the rewriting of the software code and continually modernizing existing combat systems, while adding new capabilities over the operational life of the aircraft. Over time, fleet knowledge will allow the US Navy and its partners to understand how best to maintain and support the aircraft while operating the missions effectively in support of global operations.

Reflecting on the visit there are five key takeaways from our discussions with Navy Jax.

A key point is how the USN is approaching the P-8/Triton combat partnership, which is the integration of manned, and unmanned systems, or what are now commonly called “remotes”. The Navy looked at the USAF experience and intentionally decided to not build a the Triton “remote” operational combat team that is stovepiped away from their P-8 Squadrons.

The team at Navy Jax is building a common Maritime Domain Awareness and Maritime Combat Culture and treats the platforms as partner applications of the evolving combat theory. The partnership is both technology synergistic and also aircrew moving between the Triton and P-8

The P-8 pilot and mission crews, after deploying with the fleet globally can volunteer to do shore duty flying Tritons. The number of personnel to fly initially the Tritons is more than 500 navy personnel so this is hardly an unmanned aircraft. Hence, inside a technological family of systems there is also an interchangeable family of combat crews.

With the P-8 crews operating at different altitudes from the Triton, around 50K, and having operational experience with each platform, they will be able to gain mastery of both a wide scale ocean ISR and focused ASW in direct partnership with the surface navy from Carrier Strike Groups, ARG/MEUs to independent operations for both undersea and sea surface rather than simply mastering a single platform.

This is a visionary foundation for the evolution of the software upgradeable platforms they are flying as well as responding to technological advances to work the proper balance by manned crews and remotes.

The second key point is that the Commanders of both P-8 aviator and the soon to be operational Triton community understand that for transformation to occur the surface fleet has to understand what they can do. This dynamic “cross-deck” actually air to ship exchange can totally reshape surface fleet operations. To accelerate this process, officers from the P-8 community are right now being assigned to surface ships to rework their joint concepts of operations.

Exercises are now in demonstration and operational con-ops to explain and real world demonstrate what the capabilities this new and exciting aspect of Naval Air can bring to the fleet. One example was a recent exercise with an ARG-MEU where the P-8 recently exercised with the amphibious fleet off of the Virginia Capes.

The third key point is that the software upgradeability aspect of the airplane has driven a very strong partnership with industry to be able to have an open-ended approach to modernization. On the aircraft maintenance and supply elements of having successful mission ready aircraft it is an important and focused work in progress both inside the Navy (including Supply Corps) and continuing an important relationship with industry, especially at the Tech Rep Squadron/Wing level.

The fourth point is how important P-8 and Triton software upgradeability is, including concurrent modification to trainer/simulators and rigorous quality assurance for the fidelity of the information in shaping the future of the enterprise. The P-8s is part of a cluster of airplanes which have emerged defining the way ahead for combat airpower which are software upgradeable: the Australian Wedgetail, the global F-35, and the Advanced Hawkeye, all have the same dynamic modernization potential to which will be involved in all combat challenges of maritime operations.

It is about shaping a combat learning cycle in which software can be upgraded as the user groups shape real time what core needs they see to rapidly deal with the reactive enemy. All military technology is relative to a reactive enemy. It is about the arsenal of democracy shifting from an industrial production line to a clean room and a computer lab as key shapers of competitive advantage.

The fifth point is about weaponization and its impact. We have focused for years on the need for a weapons revolution since the U.S. forces, and as core allies are building common platforms with the growth potential to operate new weapons as they come on line. The P-8 is flying with a weapon load out from the past, but as we move forward, the ability of the P-8 to manage off board weapons or organic weapons will be enabled.

For example, there is no reason a high speed cruise or hypersonic missile on the hard points of the P-8 could not be loaded and able to strike a significant enemy combat asset at great distance and speed. We can look forward to the day when P-8s crews will receive a Navy Cross for sinking a significant enemy surface combatant.

In short, the P-8/Triton is at the cutting edge of naval air transformation within the entire maritime combat enterprise. And the US Navy is not doing this alone, as core allies are part of the transformation from the ground up.

MDA-Strike-Capability

BIDEC 19 Presentation Regarding the Integrated Distributed Force

Interview at Seapower 19 in Sydney Australia, October 2019 With Regard to the Integrated Distributed Force