By Robbin Laird

Recently, both the UK Ministry of Defence and Norwegian Ministry of Defence websites highlighted the meeting between the UK Minister of Defence and the Norwegian States Security of Defence held at RAF Lossiemouth in August 2019.

Defence Minister Anne-Marie Trevelyan hosted Norwegian State Secretary Tone Skogen to discuss NATO and the UK’s role in the North Atlantic.

The UK is investing £3 billion in nine new Boeing Poseidon P-8A maritime patrol aircraft, with Norway committing to a further five. The aircraft are sophisticated submarine-hunters designed to scout complex undersea threats.

The aircraft will work together, and with NATO allies, to combat a range of intensifying threats in the North Atlantic, including increased hostile submarine activity.

Defence Minister Anne-Marie Trevelyan said:

“The UK’s maritime patrol aircraft programme demonstrates our ongoing commitment to working with international allies in the North Atlantic, strengthening our alliances with valued partners such as Norway.

“Our two nations share basing facilities, undergo cold weather training together and patrol the seas and skies side-by-side allowing us to successfully face down the growing threats from adversaries in the North Atlantic region.”

During the visit, the defence ministers experienced a demonstration flight in a US Navy Poseidon P-8A aircraft.

Norwegian State Secretary Tone Skogen said:

“The UK and Norway have a long history of cooperation on maritime surveillance and operations. This close relationship will only improve now that we will operate the same type of MPA, the P-8 Poseidon. UK and Norwegian priorities are aligned in the North Atlantic, and we look forward to a close and integrated partnership in meeting common challenges within the realm of maritime security.”

The entire nine-strong UK Poseidon P-8A fleet will be based at RAF Lossiemouth. The first aircraft has been built and has just completed its first test flight. It will be handed over to the RAF in the United States later this year and arrive in Scotland early in 2020.

Last year, the station broke ground on construction of a £132 million strategic facility for the new fleet, to be completed in 2020. The new facility is being constructed by Elgin-based Robertson Northern and will comprise a tactical operations centre, an operational conversion unit, squadron accommodation, training and simulation facilities and a three-bay aircraft hangar.

When all of these developments are complete there will be 470 additional service personnel based at RAF Lossiemouth, taking the total number of people employed there to 2,200.

RAF Lossiemouth is one of the most important air stations in the UK: it is already home to four RAF Typhoon squadrons – half of the RAF Typhoon Force – which conducts air policing work to protect the UK’s airspace from unwanted intrusion, and also on behalf of NATO in Eastern Europe to reassure allies.

The UK’s NATO commitments also include sending four RAF Typhoons to conduct air policing in Icelandic skies for the first time later this year. Such operations allow the RAF to develop valuable skills in new and challenging environments, as well as working closely with allies to protect Euro Atlantic security.

Earlier this month, RAF Typhoons benefitted from a £350 million contract with Rolls-Royce to support the maintenance of their EJ200 engines up to 2024.

The featured photo shows Defence Minister Anne-Marie Trevelyan and Norwegian State Secretary Tone Skogen meeting at RAF Lossiemouth.

Credit: UK MOD

We have highlighted the significance of allied cooperation in shaping new capabilities during the strategic shift back to direct defense of Europe over the past few years, and are focusing on this shift in our new book to be published next year.

The ASW piece is especially significant but also is being built differently from the time of the Cold War.

In this article published on July 19, 2017, we highlighted the crafting of a maritime domain strike enterprise in the North Atlantic with the new systems enabling the effort.

That article follows:

2017-07-19 Recently, the UK, Norway and the US signed an agreement to work together on ASW in the North Atlantic, which will leverage the joint acquisition of the P-8 aircraft.

This agreement and the evolution of the aircraft is yet another example of the US and its allies standing up at the same time an evolving defense capability in which allies are clearly key partners in shaping the evolution of a core combat capability.

To lay down a foundation for a 21st century approach, the US Navy is pairing its P-8s with a new large unmanned aircraft, and working an integrated approach between the two. In a very narrow sense, the P-8 and Triton are “replacing” the P-3.

But the additional ISR and C2 enterprise being put in place to operate the combined P-8 and Triton capability is a much broader capability than the classic P-3. Much like the Osprey transformed the USMC prior to flying the F-35, the P-8/Triton team is doing the same for the US Navy as the F-35 comes to the carrier air wing.

The team at Navy Jax is building a common Maritime Domain Awareness and Maritime Combat Culture and treats the platforms as partner applications of the evolving combat theory. The partnership is both technology synergistic and also aircrew are moving between the Triton and P-8.

The P-8s is part of a cluster of airplanes which have emerged defining the way ahead for combat airpower which are software upgradeable: the Australian Wedgetail, the global F-35, and the Advanced Hawkeye, all have the same dynamic modernization potential to which will be involved in all combat challenges of maritime operations.

It is about shaping a combat learning cycle in which software can be upgraded as the user groups shape real time what core needs they see to rapidly deal with the reactive enemy.

All military technology is relative to a reactive enemy.

As Ed Timperlake has noted “It is about the arsenal of democracy shifting from an industrial production line to a clean room and a computer lab as key shapers of competitive advantage.”

https://sldinfo.com/the-arrival-of-a-maritime-domain-awareness-strike-capability-the-impact-of-the-p-8triton-dyad/

And from the ground up, the US Navy is doing this with the Brits, the Australians, and soon the Norwegians will join into the effort.

Canada is a key player in the North Atlantic ASW effort.

There is a great deal of respect by the Brits, the Australians and Norwegians for the professionalism and competence of the Canadian ASW forces.

But there is concern with the level of funding effort which the Canadian government makes to this effort and to the uncertainty about the Canadian modernization path.

The Royal Australian Air Forces first P-8A Poseidon, A47-001 flys in formation with a current AP-3C Orion over their home Base of RAAF Base Edinburgh in South Australia.Credit: Australian Department of Defence

Much like the F-35 pilots and maintainers for allies are being trained initially in the United States and then standing up national capabilities, the same is happening with the P-8/Triton allies whereby the Brits and Australians are training at Jax Navy and this will most certainly happen with the Norwegians as well.

In fact, recently an RAF pilot has gone beyond 1,000 flight hours on the P-8 at Jax Navy.

And the allies are doing training for the entire P-8 force as well.

The Australians are buying the P-8 and the Triton and the Brits and Norwegians the P-8s but will work with the US Navy as it operates its Tritons in the North Atlantic area of interests.

These allies are working key geographical territory essential to both themselves and the United States, so shared domain knowledge and operational experience in the South Pacific and the North Atlantic is of obvious significance for warfighting and deterrence.

And given the relatively small size of the allied forces, they will push the multi-mission capabilities of the aircraft even further than the United States will do and as they do so the U.S. can take those lessons as well.

There is already a case in point.

The Australians as a cooperative partner wanted the P-8 modified to do search and rescue something that the US Navy did not build into its P-8s. But now that capability comes with the aircraft, something that was very much a requirement for the Norwegians as well.

And the US Navy is finding this “add-on” as something of significance for the US as well.

I have visited the Australian and British bases where the P-8s and, in the case of the Aussies, the Triton is being stood up. And I have talked with the Norwegians during my visit in February about their thinking with regard to the coming MDA enterprise.

It is clear from these discussions, that they see an F-35 like working relationship being essential to shaping a common operational enterprise where shared data and decision making enhance the viability of the various nation’s defense and security efforts.

During my visit to RAAF Edinburgh, which is near Adelaide in South Australia where the Aussies will build their new submarines, I had a chance to discuss the standup of the base and to look at the facilities being built there.

As with the F-35, new facilities need to be built to support a 21st century combat aircraft where data, and decision-making tools are rich and embedded into the aircraft operations.

At the heart of the enterprise is a large facility where Triton and P-8 operators have separate spaces but they are joined by a unified operations center.

It is a walk through area, which means that cross learning between the two platforms will be highlighted.

This is especially important as the two platforms are software upgradeable and the Aussies might well wish to modify the mission systems of both platforms to meet evolving Australian requirements.

The P-8 and Triton integrated facility being built at RAAF Edinbourgh, near Adelaide in South Australia. Credit: Australian Ministry of Defence

And in discussions with senior RAAF personnel, the advantage of working with the US Navy and other partners from the ground up on the program was highlighted.

“In some ways, it is like having a two nation F-35 program. Because we are a cooperative partner, we have a stake and say in the evolution of the aircraft.

“And this is particularly important because the aircraft is software upgradeable.

“This allows us working with the USN to drive the innovation of the aircraft and its systems going forward.”

“We’ve been allowed to grow and develop our requirements collectively. We think this is very far sighted by the USN as well. I think we’ve got the ability to influence the USN, and the USN have had the ability to influence us in many of the ways that we do things.”

“We will be doing things differently going forward. It is an interactive learning process that we are setting up and it is foundational in character. We’re generating generation’s worth of relationship building, and networking between the communities. We are doing that over an extended period of time.”

“For about three years we have been embedding people within the USN’s organization. There are friendships that are being forged, and those relationships are going to take that growth path for collaboration forward for generations to come.

“When you can ring up the bloke that you did such and such with, have a conversation, and take the effort forward because of that connection. That is a not well recognized but significant benefit through the collaborative program that we’re working at the moment.”

“We are shaping integration from the ground up. And we are doing so with the Australian Defence Force overall.”

I visited RAF Lossiemouth as well where the Brits are standing up their P-8 base.

With the sun setting of the Nimrod, the RAF kept their skill sets alive by taking Nimrod operators and putting them onboard planes flying in NATO exercises, most notably the Joint Warrior exercises run from the UK.

This has been a challenge obviously to key skill sets alive with no airplane of your own, but the US and allied navies worked collectively as the bridge until the Brits get the new aircraft.

https://sldinfo.com/keeping-skill-sets-alive-while-waiting-for-a-replacement-aircraft-from-nimrod-to-p-8/

And the base being built at Lossiemouth will house not only UK aircraft, but allow Norwegians to train, and the US to operate as well.

Indeed, what was clear from discussions at Lossie is that the infrastructure is being built from the ground up with broader considerations in mind, notably in effect building a 21st century MDA highway.

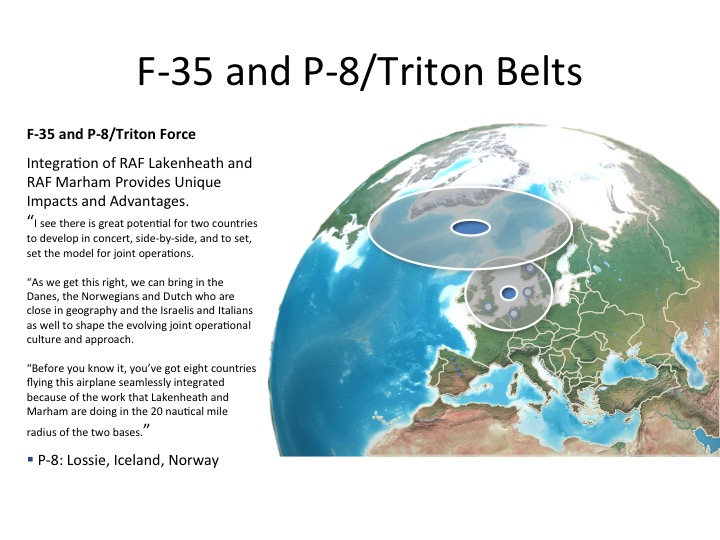

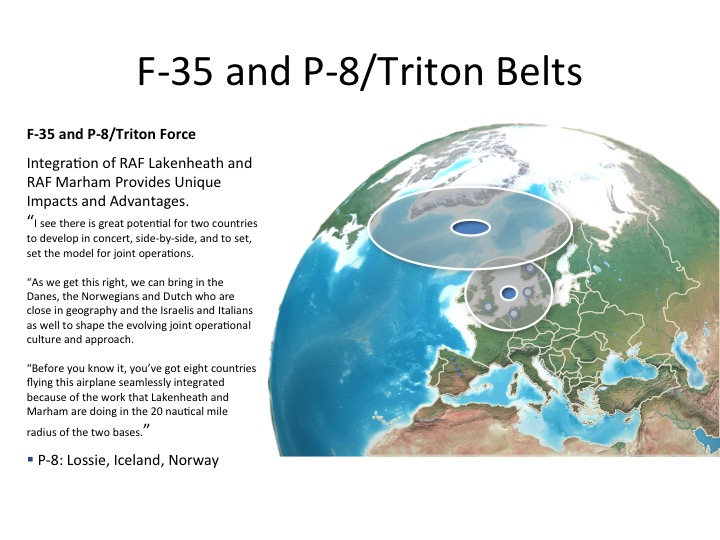

The RAF is building capacity in its P-8 hangers for visiting aircraft such as the RAAF, the USN, or the Norwegian Air Force to train and operate from Lossiemouth. In many ways, the thinking is similar to how building the F-35 enterprise out from the UK to Northern Europe is being shaped as well.

https://sldinfo.com/the-p-8-coming-to-raf-lossiemouth-shaping-the-infrastructure-for-uk-and-nato-defense-in-the-north-atlantic/

In effect, an MDA highway being built from Lossie and the F-35 reach from the UK to Northern Europe are about shaping common, convergent capabilities that will allow for expanded joint and combined operational capabilities.

At this is not an add on, but built from the ground up.

Flying the same ISR/C2/strike aircraft, will pose a central challenge with regard to how best to share combat data in a fluid situation demanding timely and effective decision-making?

The UK is clearly a key player in shaping the way ahead on both the P-8 and F-35 enterprises, not just by investing in both platforms, but building the infrastructure and training a new generation of operators and maintainers as well.

At the heart of this learning process are the solid working relationships among the professional military in working towards innovative concepts of operations.

This is a work in progress that requires infrastructure, platforms, training and openness in shaping evolving working relationships.

Having visited Norway earlier this year and having discussed among other things, the coming of the P-8 and the F-35 in Norway, it is clear that what happens on the other side of the North Sea (i.e., the UK) is of keen interest to Norway.

And talking with the RAF and Royal Navy, the changes in Norway are also part of broader UK considerations when it comes to the reshaping of NATO defense capabilities in a dynamic region.

In my interview with the new Chief of Staff of the Norwegian Air Force, Major General Skinnarland, she underscored how important she saw the collaborative from the ground up approach of operating new systems together.

Referring to the F-35, she argued that “With the UK, the US, the Danes and the Dutch operating the same combat aircraft, there are clear opportunities to shape new common operational capabilities…

“And with the P-8s operating from the UK, Iceland, and Norway can shape a maritime domain awareness data capability which can inform our forces effectively as well but again, this requires work to share the data and to shape common concepts of operations.

“A key will be to exercise often and effectively together. To shape effective concepts of operations will require bringing the new equipment, and the people together to share experience and to shape a common way ahead.”

In effect, a Maritime Domain Awareness highway or belt is being constructed from the UK through to Norway.

A key challenge will be establishing ways to share data and enable rapid decision-making in a region where the Russians are modernizing forces and expanded reach into the Arctic.

Obviously a crucial missing in action player in this scheme is Canada. And in my discussions with Commonwealth members and Northern Europeans there is clear concern for disappearing Canadian capabilities.

Perhaps one way to enhance modernization of Canadian forces along with the Brits and the Norwegians would be to shape a joint buy with the UK and Norway to procure a set of Tritons in common and work common data sharing arrangements.

Or perhaps a model to sell data rather than buy aircraft might be considered as well which has been the model whereby Scan Eagle has operated with the USMC.

As the COS of the Norwegian Air Force put the challenge:

“We should plug and play in terms of our new capabilities; but that will not happen by itself, by simply adding new equipment.

“It will be hard work.”

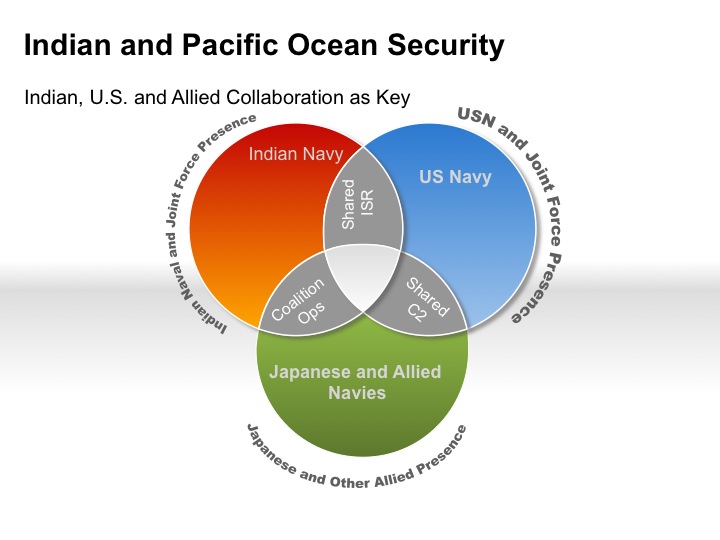

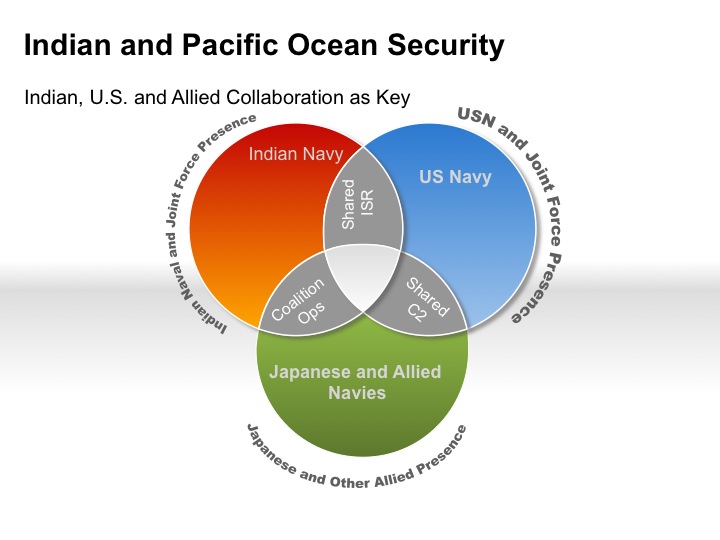

And that will include the possibility of an expanded relationship with India as well.

The Indians have purchased P-8s as well but have put unique systems on the aircraft to do many of the missions.

There is an inherent potential for India to work with the other P-8 partners as well but full cooperation will require reaching a number of data sharing agreements with the other P-8 partners.

In effect, the P-8 will be part of the evolving naval collaborative framework between the Indians and the U.S. as well as with other allies.

What makes the P-8 an especially interesting platform is that it is a shared platform between India and the U.S. with others (such as Australia) likely to join in and this sharing of a platform can provide a tool for enhancing collaboration in the daunting task of shaping effective ISR for 21st century maritime missions.

The opportunity is inherent in the technology; the challenge will be to shape the collaborative approach and shared concepts of operations.

The threats require nothing less.

Editor’s Note: This piece was first published by Breaking Defense.

Allies And The Maritime Domain Strike Enterprise