By Robbin Laird

During my most recent visit to London, a senior defense official flat out stated: “With the return of geography, the focus needs to be clearly on our Northern and Southern Flanks, and this means the emphasis needs to be placed upon air-naval integration.

“The Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force need to find ways to work much more effective integration.

“And our new carrier provides a means whereby we can do so.”

With the coming of Brexit, there is a natural withdrawal of military attention from what used to be called the Central Front during the Cold War days, and a renewed focus on the flanks.

France and Germany have asserted that their defense collaboration will take care of Europe’s defense and providing the maneuver forces and space for the defense of Europe’s new front line in Poland and the Baltics, and the UK’s contribution will be reduced to reinforcing efforts, not leading them in this continental European sector.

The new carrier is a key piece of sovereign real estate around which flank defense will be generated. It is also a focal point for RAF and Royal Navy integration of the sort which a transformed force will need to deliver to the nation.

During my visit to Portsmouth, England and to RAF Marham in early May 2018, I visited senior Royal Navy and defense personnel involved in the standing up of the UK carrier strike capability.

After my morning briefings with the Royal Navy with regard to preparing the carrier for its role as the flagship of a maritime strike group, I had a chance to discuss the way ahead with the commander of the UK Carrier Strike Group, Commodore Andrew Betton and with Colonel Phil Kelly, Royal Marines, COMUKCSG Strike Commander.

The new UK carriers are coming at a time when there is a broader UK and allied defense transformation and a strategic shift from counter-insurgency to higher end operations.

The new UK carrier provides a mobile basing capability by being a flexible sea base, which can compliment UK land-based air assets, and provide a flexible asset that can play a role in the Northern Flank or the Mediterranean on a regular deployment basis and over time be used for deployments further away from Europe as well.

Commodore Betton and Col. Kelly both underscored the flexible nature of the HMS Queen Elizabeth.

The UK is building out a 21stcentury version of a carrier strike group, one which can leverage the F-35 as a multi-domain combat system and to do both kinetic and non-kinetic strike based on these aircraft, as well combine them with helicopter assault assets to do an F-35 enabled assault, or if desired, shift to a more traditional heavy helicopter assault strike.

As Commodore Betton put it: “Our new carrier offers a really flexible, integrative capability.

“The carrier can play host and is intended absolutely to play host to a carrier air wing.

“At the same time, it can provide something very different inn terms of littoral combat operations, primarily using helicopters.”

They emphasized that the Royal Navy was building new escort ships as well as new submarines and the approach to building a maritime strike group meant that working through the operational launch of the carrier was also about its ability to integrated with and to lead a 21stcentury maritime strike group.

And the new maritime strike group was being built to work with allies but just as importantly to operate in the sovereign interest of the United Kingdom.

The F-35B onboard was a key enabler to the entire strike group functions.

Commodore Betton: “The airwing enables us to maneuver to deliver effects in the particular part of the battlespace which we are operating in. You can have sea control without the airwing.

“Our air wing can enable us to be able to do that and have sufficient capability to influence the battlespace.

“You clearly do not simply want to be a self-sustaining force that doesn’t do anything to affect the battlespace decisively.

“The F-35 onboard will allow us to do that.”

Col. Kelly noted that with the threat to land air bases, it was important to have a sea base to operate from as well, either as an alternative or complement to land bases.

“The carriers will be the most protected air base which we will have. And we can move that base globally to affect the area of interest important to us.

“For example, with regard to Northern Europe, we could range up and down the coastlines in the area and hold at risk adversary forces.

“I think we can send a powerful message to any adversary.”

Commodore Betton added that the other advantage of the sea base is its ability to be effective on arrival.

“If you have to operate off of land, you have to have the local permission. You have to move assets ashore. You have to support assets ashore. And you have to protect the land base. The sea base has all of that built in.

“And there is nothing austere about our carriers in terms of operating aircraft.”

“We focused on how the carrier becomes integrated with broader strike picture, for the point is not simply that the carrier itself launches F-35s or helicopters, but how the command post can manage the aircraft they launch with the distributed strike assets in the strike group, which could include land-based air or land based forces as well.”

Col. Kelly emphasized that their position was similar to the evolution of the USMC where “every platform can be a sensor or a shooter” in the battlespace.

The C2 onboard the carrier on in the air with the Crow’s nest or the F-35Bs can be part of a distributed CS system to ensure maximum effect from the strike and sensing capability of the task force and its related partners in the battlespace.

And innovations in the missile domain up to and including directed energy weapons have been anticipated in the support structure onboard the carrier.

During my visit in 2015 to the Scottish shipyard when the initial Queen Elizabeth carrier was being built, I had a chance to look at the infrastructure onboard the ship to support weapons as well as was briefed on the significant power generation capabilities onboard the ship which clearly allow it to when appropriate technology is available to add directed energy weapons.

In addition, to the longer-range weapons already in train and the ones which will be developed in the decade ahead, the British carriers are being built to be able to handle rolling landing which allow the F-35s to come back onto the ship with weapons which have not been used during the mission.

The second carrier, HMS Prince of Wales is the first of the two carriers to be fitted with this capability which will be further tested when it comes to the United States in a couple of years for its F-35 integration trials as well.

In short, the new carrier is being built with “growthability” in mind, in terms of what it can do organically, and what it can leverage and contribute to the maritime task force, and reach out into the battlespace to work effectively with other national or allied assets operating in the area of interest.

The Changing Alliance Context for UK Defense Policy

For the UK, Brexit is at the heart of the change in the alliance structure as well as the question of US global defense policy in flux.

With the projected withdrawal from the European Union, not only are the political-economic relationships with Europe in flux but key security working relationships as well.

Brexit is a process which have a major impact on the UK and Europe for sure.

And no matter what the Brexit negotiated outcome that will be sorted out between the EU and the UK, both continental Europe and the UK will have to find a way to work together going forward.

The UK has a long history of dealing with continental Europe as does continental Europe with the United Kingdom, and certainly not all such experiences have been peaceful.

Brexit is an episode of history which will be ingested as the UK and Europe go forward in the next phase of their interactions.

Clearly, the UK and as well as major continental powers will sort out a way ahead, but as they do so several trajectories of developments will be set in motion.

Brexit has a number of key impacts on the future of European defense and certainly NATO as well.

First, the UK is a major defense power within Europe.

What is its relationship to the continent after Brexit?

What does a post-Brexit defense policy look like for Britain?

Second, what impact will Brexit have on the internal cohesion of UK defense policy?

What role for Scotland and England?

And how will the Irish question intrude into the defense equation?

Third, will continental Europe meet the demands of enhanced defense responsibility for its own defense?

How will France and Britain work together?

Where will German defense policy focus its attention and its resources?

What impact will the UK have within European defense organizations or not?

Fourth, what impact will Brexit have upon the relationships between UK and continental defense and aerospace companies?

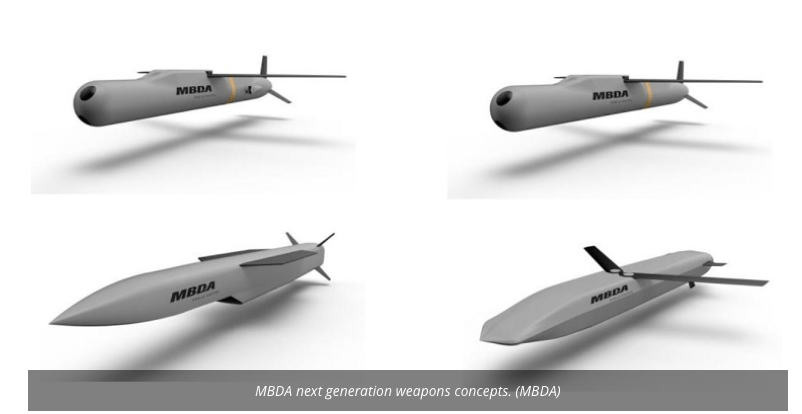

Airbus, Thales, MBDA, and Leonardo all have major working relationships and facilities in the UK.

What is their fate and how will these relationships work in practical terms as movement of personnel, taxes and import and export issues get sorted?

Will joint investments continue between Britain and the continent within these companies?

What is the future of Eurofighter if the UK and continental European relationship is disrupted?

Will France and UK co-investments in missiles via MBDA continue uninterrupted?

In other words, there are a number of key questions to consider determining the fate of European and UK defense in dealing with the looming Brexit impacts.

The defense industrial side of Brexit is clearly tied up with the general dynamics of whatever trade and circulation of skills and labor generally agreed to between the UK and the European Union.

But defense is an area where exceptions in regulations are often the rule; but they clearly are affected by the general state of trade, notably the commercial aerospace trade arrangements.

Brexit is occurring at a time of profound change in Europe, triggered perhaps in part by Brexit, but due to a wide range of dynamics which are clearly leading to the politics within nations focused on their future and the kind of European working relationships those nations wish to see.

It is very clear that Brexit provides a major challenge to UK defense and aerospace industry given that the major focus and major capabilities in those sectors rests on their role in global supply chains and programs, many of which are European.

Airbus is a central player in the UK aerospace industry, and in defense as well. Leonardo is many ways a UK-Italian company. MBDA is a Franco-UK company with German and Italian aspects. Thales has a very large UK component which both complements and challenges its French dominant part of the company.

With the very significant uncertainties facing Europe and the UK with regard to Brexit, NATO is in flux as well with the return of direct defense to Europe. With the seizure of Crimea by the Russians in 2014, NATO recognized a new historical challenge: how to deal with the return of Russia as a direct threat to Europe?

But this is not the return of the Cold War, as the Warsaw Pact has dissolved and both the European Union and NATO have extended themselves to the Russian border. They have done so without adding new defense forces or capabilities, and indeed Europe has experienced a significant decline in defense expenditures.

At the same time new challenges have been added.

The Russians have used a new form of warfare, hybrid warfare, to achieve their objectives in Ukraine and have launched major cyber threats as well. NATO Europe has dismantled much of its direct defense infrastructure and now with the rise of the cyber challenge has a more comprehensive threat system to deal with.

The challenge of building a 21st century defense infrastructure and rebuilding NATO forces is significant and at the same time, Europe is now confronting the impact not only of the Russians but other authoritarian states and movements.

The Nordics are clearly reworking their defense capabilities and approaches and the UK is finding a natural ally with regard to a rethink as well with how best to rework both national and allied defense policies for direct defense. This process is facilitated in part by the acquisition of some new systems in common, notably the F-35 and the P-8 as well as other collaborative efforts.

But as of 2019, it is difficult with certainty to know what the relationship among UK defense modernization, its relationship with the European Union and the dynamics of change within the NATO alliance will shape the ultimate direct defense capability’s and approach for the United Kingdom.

The featured photo shows the HMS Queen Elizabeth at Sea. Credit: UK MoD

For the full report looking at UK and Australian approaches to defense transformation, see the following:

Fifth-Generation Enabled Military Transformation: Australia, the UK and Shaping a Way Ahead