The Zephyr S is an interesting aircraft, which falls, in the area between satellites and high altitude manned aircraft, and opens up interesting potential applications to civil and military related missions.

According to Airbus, the Zephyr S can provide a number of potential applications for users.

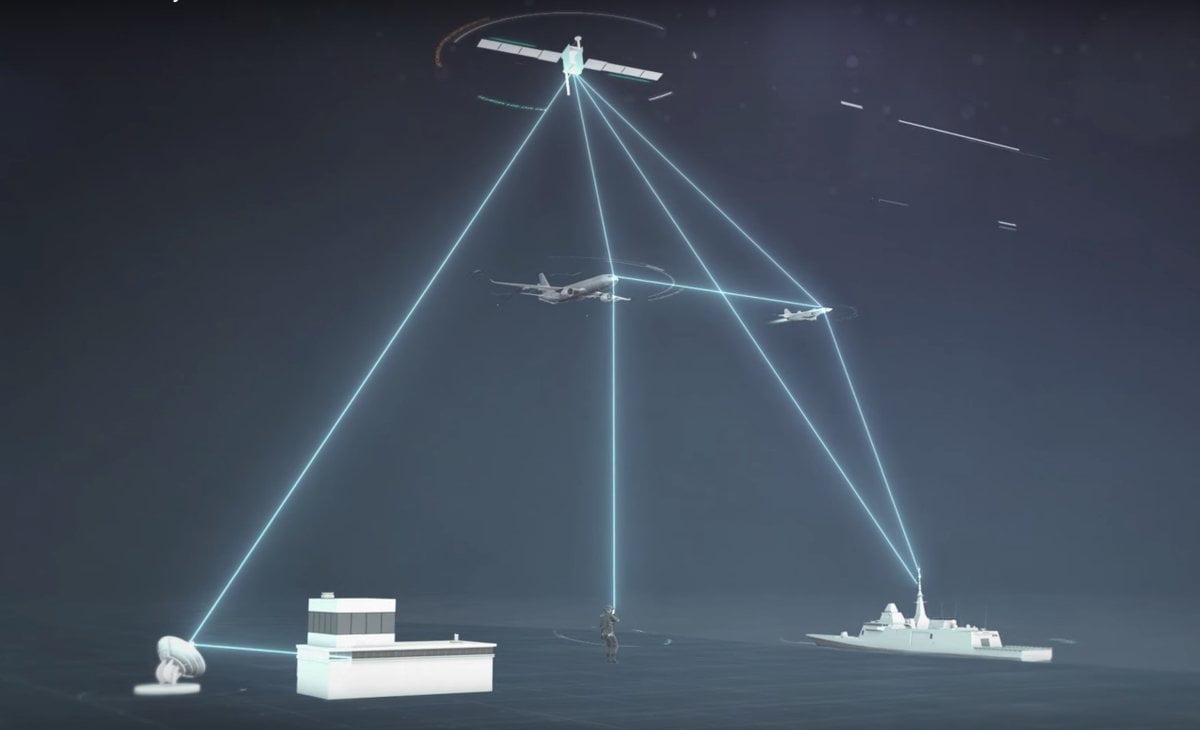

The Zephyr S is a solar-powered aircraft, providing a wide scope of applications, ranging for example from maritime surveillance and services, border patrol missions, communications, forest fire detection and monitoring, or navigation.

Operating in the stratosphere at an average altitude of 70,000 feet / 21 kilometers, the ultra-lightweight Zephyr has a wingspan of 25 meters and a weigh of less than 75kg, and flies above weather (clouds, jet streams) and above regular air traffic, covering local or regional footprints. Ideally suited for “local persistence” (ISR/Intelligence, Surveillance & Reconnaissance), the Zephyr has the ability to stay focused on a specific area of interest (which can be hundreds of miles wide) while providing it with satellite-like communications and Earth observation services (with greater imagery granularity) over long periods of time without interruption.

Not quite an aircraft and not quite a satellite, but incorporating aspects of both, the Zephyr has the persistence of a satellite with the flexibility of a UAV.

The only civil aircraft that used to fly at this altitude was Concorde and only the famous military U2 and SR-71 Blackbird could operate at similar levels.

The Zephyr successfully achieved several world records, including the longest flight duration without refueling.

Two recent updates on the Zephyr air vehicle have been recently provided by new release from Airbus Defence and Space.

The first dated July 25, 2018, highlighted the air vehicle’s launch to break the aircraft world endurance record.

Zephyr S, Airbus’ High-Altitude-Pseudo-Satellite, has surpassed the current flight endurance record of an aircraft without refueling of 14 days, 22 minutes and 8 seconds and continues to pioneer the stratosphere.

The Zephyr aircraft departed for its maiden flight from Arizona, USA on 11th July 2018.

This first flight of the Zephyr S aims to prove and demonstrate the aircraft capabilities, with the final endurance record to be confirmed on landing.

The second dated July 16, 2018 focused on the establishment of the first serial production facility for the Zephyr, which also highlights the working relationship between the UK with the company as well as the engagement of the US government as well:

The Zephyr S is the first production aircraft of the Zephyr programme, previous Zephyr units being Research and Development prototypes.

Zephyr is the world’s leading, solar–electric, stratospheric Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). It harnesses the sun’s rays, running exclusively on solar power, above the weather and conventional air traffic; filling a capability gap complimentary to satellites, UAVs and manned aircraft to provide affordable and persistent local satellite-like services.

Named after the late Chris Kelleher, the inventor of Zephyr, the opening of production facilities is part of a significant focus by Airbus on the Zephyr programme. The Kelleher facility represents the first serial HAPS assembly line worldwide.

“Today represents a significant milestone in the Zephyr programme. The facility is home to the world’s leading High-Altitude Pseudo Satellite and will be a showcase location, linking to our operational flight bases around the world.

“The Zephyr S aircraft is demonstrably years ahead of any other comparable system and I am beyond proud of the Airbus team for their unrivalled success. Today we have created a new future for stratospheric flight”, said Dirk Hoke, Chief Executive Officer of Defence and Space.

This programme milestone comes as the Zephyr aircraft is currently flying after having departed for its maiden flight from Arizona, USA a few days ago.

“This flight is being supported by both the UK and US governments and reflects the UK Ministry of Defence’s position as the first customer for this innovative and potentially game changing capability.

This maiden flight of the Zephyr S aims to prove and demonstrate the aircraft capabilities, with a landing date to be confirmed once the engineering objectives have been achieved. Until today, the Zephyr aircraft has logged almost 1,000 solid hours of flying time.

Added Sophie Thomas, Head of the Zephyr programme at Airbus: “Firstly, I would like to thank Defence Equipment & Support, the procurement arm of the UK MOD for their continued support of the Zephyr programme. Zephyr will bring new see, sense and connect capabilities to both military and commercial customers. Zephyr will provide the potential to revolutionise disaster management, including monitoring the spread of wildfires or oil spills. It provides persistent surveillance, tracing the world’s changing environmental landscape and will be able to provide communications to the most unconnected parts of the world.”

In future, Airbus will be flying Zephyr S from their new operating site at the Wyndham airfield in Western Australia. This has been chosen as the first launch and recovery site for the Zephyr UAV due mainly to its largely unrestricted airspace and reliable weather. The site will be operational from September 2018.

An article by Steve Ranger from ZD Net published on July 18, 2018 highlighted the possibilities for the Zephyr S:

The Zephyr has a wingspan of 25 meters and is designed to operate in the stratosphere at an average altitude of 21 kilometers — above clouds, jet streams and ozone layer, as well as regular air traffic (apart perhaps, from the odd spy-plane). Airbus wants the drone to fly for 100 days without landing (its currently record is 14 days without refuelling) and travel up to 1,000 nautical miles per day. It weighs 75kg, but can support a payload up to five times its own weight.

The drone can be used for things like surveillance and reconnaissance — the UK’s Ministry of Defence has already bought several of the unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

It could also be used to create a communication network either for civilian or military uses — Facebook recently cancelled its own plans to build high-altitude drones to deliver internet access in remote areas, but at the time said it would continue to work with partners like Airbus on such vehicles.

The Zephyr S is the first production model from the Zephyr programme; previous Zephyr aircraft were research and development prototypes; the drones will be built at a production line in Farnborough.

Sophie Thomas, head of the Zephyr programme at Airbus told ZDNet: “The vision was there over ten years ago. What we’ve been waiting for and working on is the technology developments in different areas like battery technology and the the solar array — for that to be ready and available to the standard we need to make this a really viable product. That’s where we are today.”

Thomas said operating in the stratophere gives the drone two advantages over satellites: “The first is that you are much closer to the Earth, so you can get far higher-resolution imaging. Secondly for communications you get reduced latency. The beauty of it is we have an endurance that is really powerful, so we can persist for over 100 days, yet the flexibility of being able to retask.”

The UAV is significantly cheaper than satellites and the modular design can take different technology payloads, added Thomas.