2017-09-01 On August 23, 2017, the Williams Foundation held a seminar on the future of electronic warfare. The seminar was begun with a very thoughtful overview on the history airborne electronic attack within the RAAF.

This perspective was provided by Group Captain Andrew Gilbert, Director of the Air Power Development Centre, RAAF.

His presentation follows.

To lay the foundation for today’s seminar, I have been asked to provide an historical perspective on the development of electronic attack in the RAAF. If I were to stick with that riding instruction, this would be quite a short presentation because, put simply the RAAF has no significant operational history with airborne electronic attack.

Let me be clear, I am not suggesting that the RAAF has not been interested in developing an electronic attack capability. The RAAF has had an enduring interest in electronic warfare (EW) predating the Second World War, and while the focus of our developments, modest as they may have been, were in the realms of electronic support and electronic protection, the RAAF was fully aware of the theory and possibilities of airborne electronic attack, as demonstrated by the acquisition of

Electronic Counter Measure (ECM) pods for our fighters, and our dabbling with anti- radiation missiles. The issue was no threat was sufficiently compelling to justify the investment expense or, more appropriately, the opportunity cost that would have been required to develop an electronic attack capability. This is now no longer the case.

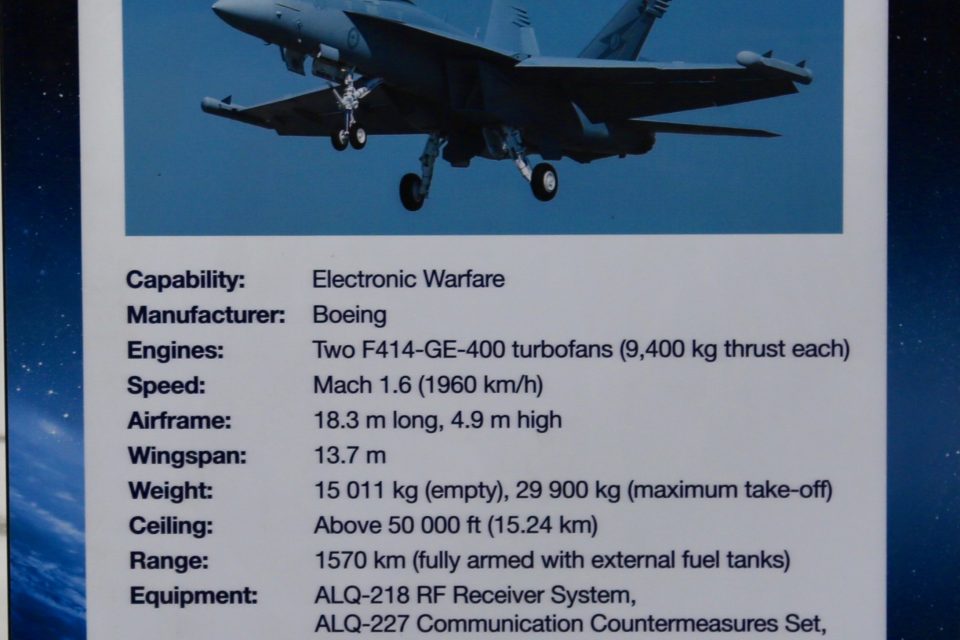

The ability to control, exploit, and deny the electromagnetic spectrum, or the EMS, has become a defining feature of modern warfare, and is a capability that is vital to the success of a fifth-generation force. As regional military’s continue their modernisation programs and we see the rise of increasingly tech-savvy non-state adversaries, the RAAF could no longer afford to ignore the requirement for air power to deny, degrade, and disrupt our potential adversary’s ability to exploit the EMS. In this respect, the EA-18G Growler represents a vital new air power capability for the joint force.

But we have to be wary of assuming that the acquisition of 12 aircraft represents “Mission Accomplished” for airborne EW in the RAAF. Rather, we need to view the Growler as a missing piece of an ever-evolving EW puzzle.

The aim of my presentation today is to describe that puzzle in broad terms, and highlight how the evolution of airborne EW has been defined by an ongoing process of action-reaction; one in which developments in the ability exploit the EMS have driven advances in the ability to deny it. This process will continue. The key to future success lies in getting ahead of the curve, developing an attitude to EW that approaches the control and exploitation of the EMS in the joint force.

Electronic Warfare up to the End of the Second World War

The concept of EW, though not the term, dates back to the American Civil War, when Confederate cavalry regularly intercepted and misdirected Union message traffic, and cut Union telegraph wires.1 The use of kinetic force to disrupt an adversary’s use of the EMS was also widely used during the First World War. In fact, Australia’s first foray into electronic attack took this form, when in November 1915 Thomas White of the Australian Flying Corps’ Mesopotamian Half-Flight flew behind enemy lines to destroy Turkish telegraph lines, landing next the target wires and destroying them with the aid of guncotton charges.2 To call these types of operations electronic attack is to stretch the definition of the term, but I use these early examples to highlight the earliest manifestations of the action-reaction cycle in electronic warfare. When an adversary finds a way to exploit the EMS, a means was found to deny it.

EW, as we know it today, really emerged as a discreet role for air power during the Second World War. During the interwar period a number of advances in radar and communications technology in Europe, Asia and America, offered new possibilities for the exploitation of the EMS for use un surveillance, communications, and navigation. The British Chain Home radar system is undoubtedly the most famous example of the recognition of the EMS as an operational enabler. But other examples abound. The Germans, Japanese, Soviets and American also developed radio and radar technology, with varying degrees of success, in the lead up to the war.

As the operational impact of the exploitation of the EMS began to be observed on both sides of the Second World War, attempts to deny the spectrum quickly emerged. In 1940, British scientists developed a method of disrupting the German’s use of Lorenz radio beams to guide Luftwaffe bombers onto their British targets. With the introduction of beam jammers in 1940 and 1941, the British were able to render the German Lorenz beam system largely ineffective. In March 1941 for example, of 89 beam bombing missions flown by the Luftwaffe, only 18 resulted in the aircraft receiving the bomb release signal.3 An excellent example of a successful early application of electronic attack in shaping the employment of air power.

Actual airborne electronic attack began to take form in the skies over Germany as specialised British bombers belonging to the RAF’s Number 100 (Bomber Support) Group, including the RAAF’s 462 Squadron Lancasters, began flying missions to specifically disrupt the German air defence network.4 Using window, thin strips of aluminium designed to spoof and deceive German radar, the British were able to reduce night bomber attrition rates by hiding the incoming raids, or diverting the German night fighters away from them as they chased false targets on their radar screens. 100 Group were also engaged in jamming Luftwaffe radio frequencies, and spoofing voice transmission, using Airborne Cigar aircraft accompanying bombing raids over Germany.5

These are just two examples of what was a dynamic and innovative process of action-reaction in the fight to exploit and deny the EMS during the Second World War. These experiences ushered in the era of electronic attack in the air domain. But the lessons learned were soon forgotten in the transition from a hot to the Cold War.

Electronic Warfare during the Cold War

The years immediately following the end of the Second World War provide excellent evidence of the action-reaction relationship between the developments in the ability to exploit the EMS and the corresponding investment in the ensuring the ability to deny the adversary’s use of the spectrum.

With the Soviet Union as the only strategic threat to the West, and the assessment being that they lacked a credible electronic threat; interest in electronic attack capabilities went into decline. The RAF’s 100 Group was disbanded in late 1945, and the US had removed the specialist EW operator from their operational B- 29s squadrons. American experience in the Korean War would highlight the shortsightedness of these decisions.

The Ground-Controlled Intercept, or GCI, systems controlling the North Korean MiG-15s, and the radar-directed North Korean searchlights and AAA took their toll on the American B-29s. By mid-1951, the Americans had lost 25 of their 100 B-29s deployed into theatre.6 In response, the US reintroduced spot-jamming capabilities on the B-29, in addition to a range of other initiatives aimed at denying North Korea’s use of the EMS. These measures significantly reduced the loss rate, with only three B-29s being lost during the 4000 sorties conducted in the last seven months of the war.7

The experience in Korea reinvigorated interest in electronic attack, but in EW terms the Korean War was, for all intents and purposes, ‘merely an extension of the Second World War’.8 The effectiveness of chaff and spot jamming had already been demonstrated in the skies over Europe. It was the advent of surface-to-air and air-to-air missile systems in the years that followed that provided the spark that re- ignited interest in the serious development of electronic attack in the Western world.

The growing sophistication of Integrated Air Defence Systems (IADS) posed a significant challenge to the operational effectiveness of Western air power from the early 1960s onwards. And experience in Vietnam and the Middle East played a critical role in shaping electronic attack into its modern form.

In Vietnam, the Soviet SA-2 surface to air missile system coupled with the GCI of the Vietnamese fighters presented American aircraft heading into North Vietnam with ‘one of the most complex electromagnetic defence threats ever to be combatted by the USAF tactical forces’.9 The US response to the threat is informative because they approached the problem a number of different ways, and in so doing laid the foundation for the modern Western approach to electronic attack.

Specialised stand-off jammers, such as the EB-66 of the USAF and the EA-6A and Bs, of the USMC and USN arrived in theatre in 1965. In the same year, the USAF Wild Weasel capability emerged on the scene, combining technology, tactics, and the cross-pollination of personnel to create a formidable SAM suppression capability.

The Israelis observed and learned EW lessons from the US, but also drew on their own bitter experiences from the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and developed a truly masterful demonstration of operational EW during the 1982 Beqaa Valley campaign. Using Remote Piloted Aircraft to deceive Syrian air defences, jamming and chaff to deny Syrian Air Defence operators an air picture, long-range artillery and rockets to attack the SAM sites and anti-radiation missiles to take out early- warning and fire control radars, the Israeli Defence Force provided the gold standard of an innovative joint approach to denying the adversary use of the EMS.

While all these innovations were happening during the Cold War, Australia remained largely uninvolved in electronic attack, due primarily to the lack of a credible threat to justify the investment. There is no better illustration of the relative priority attached to such a capability than the RAAF experience of the F-111.

As many of you are aware, one of the main reasons why the F-111s did not deploy to the 1991 Gulf War was due to the inadequacy of the self-protection systems to meet the needs of the threat environment in theatre.10 Something that was addressed subsequently with Project Echidna and other related projects.11 What is less well known, and more illustrative, is the integration trials of the AGM-88 High Speed Anti-Radiation Missile, also known as the HARM, onto the F-111 in the late 1980s. HARM was under consideration in Australia as a complement to the AGM-84 HARPOON anti-shipping missile. The broad concept of employment was for the HARM to destroy a ship’s radars, rendering it defenceless while the HARPOON would be used to sink it. ARDU conducted trials of the HARM on the F-111 in the Southern Ocean in 1987 and 1988. Unfortunately, ‘HARM was traded off in the Defence Committee for air-to-air missiles for the F/A-18 Hornets’.12

Each of these cases highlight that the consideration of electronic attack continued to be reactive to the threat posed by the adversary. US losses in Korea and Vietnam, and the heavy Israeli losses of the Yom Kippur War may have been further reduced had investment in electronic attack occurred in parallel with the development of capabilities designed to exploit the EMS. In the Australian context, the perceived absence of a credible electronic threat resulted in neglect of an electronic attack capability in the RAAF. The 1991 Gulf War changed this.

Electronic Warfare in the modern age

The Gulf War heralded a new era of air power. I won’t digress into the debate about the decisiveness of air power that conflict spawned, that is a topic for a longer discussion in a different forum, but what we saw in 1991 was a new approach to the application of air power that continues to guide our operations today. Among the most notable features of the Gulf War air campaign was the systematic dismantling of Iraq’s KARI Integrated Air Defence System through the integrated use of electronic attack, cruise missiles, and stealth aircraft.

The emergence of stealth aircraft onto the operational scene drew attention to another dimension of electronic warfare: the denial of an adversary’s ability to exploit the EMS through signature management. This approach was not new, but the F-117’s performance over Iraq in 1991validated the science of low-observables. An ‘all-aspect low observable’ signature is now one of the defining features of fifth- generation fighter aircraft.

The 1999 Serbian shoot-down of an F-117 using an SA-3 Surface to Air Missile system, a system introduced into service in 1961, however, reinforced the fact that there is no permanent solution to the challenge of electronic warfare. Every action has a reaction, and the resulting adaptation, improvisation, and innovation by an adversary can create unexpected shocks that can undermine a perceived advantage upon which our operational concepts are developed. These may not necessarily take the form of cutting edge technology, as the Serbs demonstrated in 1999 and as we have seen from the non-state actors in our current conflicts, effective adaptation can be low-tech. We must remain wary of creeping complacency derived from a perceived technological edge.

And this is what we are seeing unfold in our region. The concept of the anti- access and area-denial, or A2/AD, that has attracted so much attention over the last few years is ‘as old as warfare itself’.13 What are new and innovative are the technologies and the ways in which A2/AD strategies are being implemented by various states. In our own region, the EMS, both in its tradition manifestation and in the realm of cyber, will be one of the defining battlegrounds of any future conflict. Realisation of this fact has driven the realisation of an airborne electronic attack capability for the ADF.

My mention of cyber within the context of EW is intentional, though perhaps slightly controversial. But I include it to highlight the continually evolving nature of the non-physical dimensions of modern operations. We cannot afford to be tribal and create stove-pipes around capability based on dogmatic perspectives of domains. Cyber and EW are linked and will continue to be inextricably linked into the future, and we must account this fact for as our attitude towards EW evolves.

The RAAF’s introduction of the Growler, as I am sure we will hear from the speakers that follow me today, is an invaluable addition to Allied capability in this region and beyond. However, our potential adversaries will not remain static. They will continue to evolve their ability to exploit and deny the EMS to our detriment. Disruptive technologies such as artificial intelligence, quantum radars, Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR), and wake detection technology will enable the exploitation of non-traditional areas of the EMS and require us to continue to adapt and evolve our own electronic capabilities so as to maintain advantage in the EMS. The introduction of the Growler is not the end of the journey in electronic attack, but the beginning.

CONCLUSION

Much has changed in the 102 years since Thomas White flew his Farman pusher behind enemy lines to destroy Turkish telegraph lines. Where before we needed to rely on kinetic action to deny our adversary their use of the EMS, we now fight for the spectrum in the spectrum, with explosives now complemented by ones and zeroes. What this highlights is that the technology and tactics will invariably change; they will advance, develop and evolve. As our reliance on the EMS continues to grow, we need to ensure that we stay ahead of the curve in anticipating change and adapting to the disruption that will inevitable occur in the battle for dominance in the EMS.

The challenge laid down in this seminar is to discuss how the introduction of the Growler can be seen as a catalyst for changing the RAAF’s attitude towards electronic warfare. In my opinion, what the Growler has done has been to focus the RAAF on the missing piece long journey trying to solve the EW puzzle. We can now more clearly see and understand the full picture of what constitutes operations in the EMS look like. But what history has shown us is that the EW picture is dynamic, it evolves and changes.

To my mind, and to conclude, the RAAF needs to look beyond the Growler and continually bear in mind these three questions:

- How do we ensure the RAAF remains ahead of the action-reaction cycle in electronic warfare?

- How do we ensure we do not focus on the platforms and instead focus on the effects we need to generate? and,

- How do we ensure our airmen remain innovative and not reactionary in providing an air power perspective on the battle to control and exploit the EMS as part of the joint force?

Endnotes

1 JPR Browne and MT Thurbon, Electronic Warfare, Brassey’s Air Power: Aircraft, Weapons Systems and Technology Series, vol. 4, Brassey’s, London, 1998, p.3.

2 TW White, Guests of the Unspeakable, John Hamilton, London, 1928, pp. 46-47.

3 Alfred Price, Instruments of Darkness: The History of Electronic Warfare, Macdonald and Jane’s, London, 1967, p.49.

4 Royal Australian Air Force, Pathfinder Collection, vol. 6, Air Power Development Centre, Canberra, 2014,

p.121.

5 Price, Instruments of Darkness, p.182.

6 Browne and Thurbon, Electronic Warfare, p.26.

7 Browne and Thurbon, Electronic Warfare, p.26

8 Price, Instruments of Darkness, p.252.

9 United States Air Force, Pacific Air Forces, Directorate of Tactical Evaluation report quoted in Mark D Howard, ‘Crow Ressurection: The Future of Airborne Electronic Attack’, unpublished thesis, School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, Maxwell Air Force Base, AL, 2013, p. 9.

10 Mark Lax, From Controversy to Cutting Edge: A History of the F-111 in Australian Service, Air Power Development Centre, Canberra, 2010, p. 191.

11 Lax, From Controversy to Cutting Edge, p. 192.

12 Lax, From Controversy to Cutting Edge, p. 168.

13 Sam LaGone, ‘CNO Richardson: Navy Shelving A2/AD Acronym’, USNI News, 3 October 2016, viewed 17 August 2017, <https://news.usni.org/2016/10/03/cno-richardson-navy-shelving-a2ad-acronym>.

EW23Aug17_Gilbert Presentation notes

Lt. General (Retired) Jon Davis on a panel at the Williams Foundaton Seminar on Electronic Warfare, August 23,

Lt. General (Retired) Jon Davis on a panel at the Williams Foundaton Seminar on Electronic Warfare, August 23,