2015-06-03 By Robbin Laird

As published by our partner India Strategic

http://www.indiastrategic.in/topstories3766_A_Tale_of_Three_Carriers.htm

Newport News, Pascagoula, Mississippi, and Rosyth Scotland.

In the famous opening lines of Charles Dickens Tale of Two Cities, he noted that “it was the best of times; it was the worst of times.”

So it is for aircraft carriers.

The critics of aircraft carriers focus on their vulnerability and the rise of capabilities such as the DF-21 Chinese “carrier killer” missiles; yet new carriers are emerging tailored for 21st century operations.

It is clear that the USN, the USMC, the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy are all pursuing new carrier programmes designed to thrive, not just survive in 21st century operations.

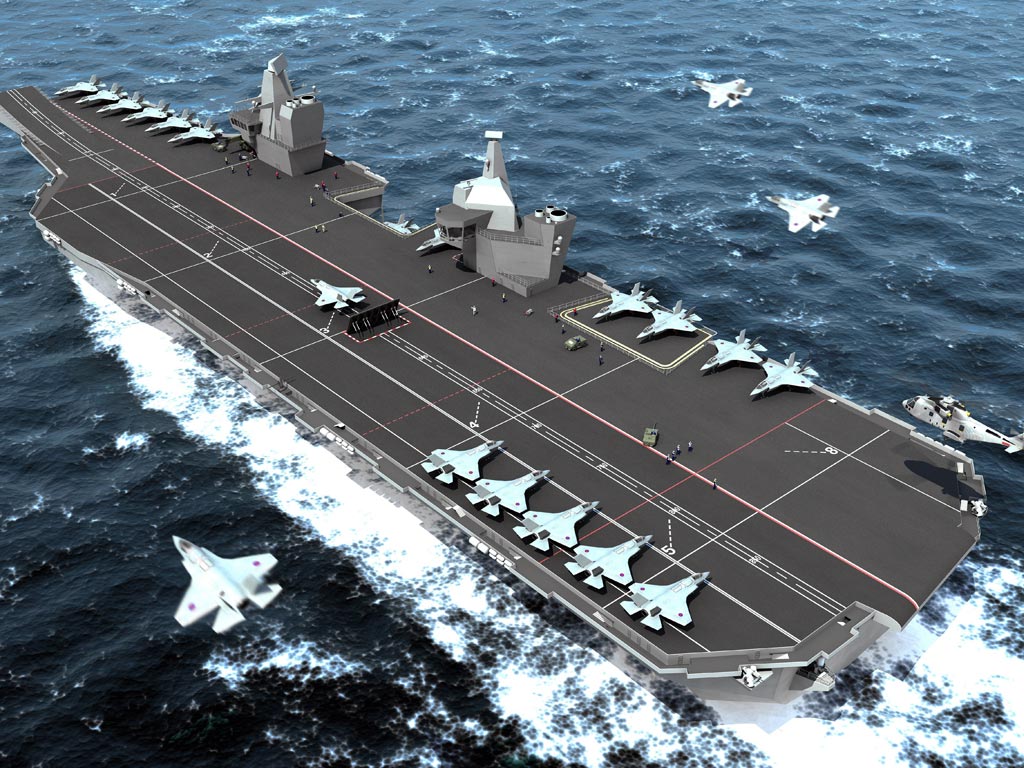

I have had the rare opportunity to be aboard all three of the new carriers: the 52,000-ton USS America, which is the amphibious assault ship ever built; the 100,000-ton CVN-78 or the USS Gerald Ford, and the 65,000 ton HMS Queen Elizabeth.

The ships have several 21st century technologies in common: the construction of vastly improved command and control (C2) capabilities, working in sync with networked forces in a distributed operational environment.

The ships will have a 40 plus service life (although combat has its own logic), and will host significant transformation with regard to the combat assets carried aboard.

But each ship is built around significant airpower modernisation.

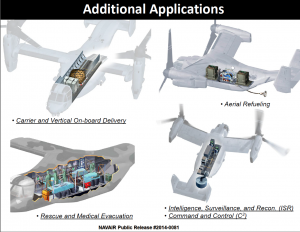

The USS America will host the Ospreys (including refueling Ospreys), F-35Bs, and the CH-53K (which can carry externally three times the load of the CH-53E); CVN-78 will see the new Hawkeye, the F-35C, and UCAS aboard her; and the HMS Queen Elizabeth is built around the F-35B as well as new airborne command capabilities.

And the Ford and the Queen Elizabeth have advanced electric power generation capabilities to take on board directed energy weapons as those capabilities evolve. Both ships have significant connectivity, with miles of fibre-optic cables, and reconfigurable C2 workstations to allow for operations against the ROMO (Range of Military Operations).

Aircraft Carriers are very good for a spectrum of operations, both in securing strategic interests through deterrence and war fighting capabilities but also for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

The three carriers mentioned have sufficient flexibility in this perspective.

They also ensure logistical integrity permitting operations from the sea without having to set up land bases.

Their air power allows them to leverage their strike capabilities for subsurface, surface, landbased and even aerial or space assets.

It was from a ship that the US shot down a satellite using a Raytheon missile. Each ship though is unique. But each one has the flexibility to adapt to the varied requirements as they arise.

USS America: Reinventing Amphibious Assault

The USS America is the largest amphibious ship ever built by the United States.

The ship has been built at the Huntington Ingalls shipyard in Pascagoula, Mississippi and departed mid-July 2014 for its trip to its initial home port at San Diego, California and then was commissioned in San Francisco in mid-October 2014. It is now undergoing its final trials and preparing to enter the fleet.

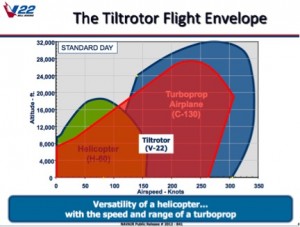

The USMC is the only tilt rotor-enabled assault force in the world.

The USS America has been built to facilitate this capability and will be augmented as the F-35B is added to the Ospreys, and helicopters already operating from the ship. Later, unmanned aircraft will also become a regular operational element.

The Boeing-Bell Osprey has obviously been a game changer, where today, the basic three ship formation used by the Amphibious Ready Group-Marine Expeditionary Unit can “disaggregate” and operate over a three-ship distributed 1,000-mile operational area.

Having the communications and ISR to operate over a greater area, and to have sustainment for a disaggregated fleet is a major challenge facing the future of the USN-USMC team. The combination of Ospreys and F-35 B will be deadly for any foe.

A major change in the ship can be seen below the flight deck, and these changes are what allow the assault force enabled by new USMC aviation capabilities to operate at greater range and ops tempo. The ship has three synergistic decks, which work together to support flight deck operations.

Unlike a traditional large deck amphibious ship where maintenance has to be done topside, maintenance is done in a hangar deck below the flight deck. And below that deck is the intermediate area, where large workspaces exist to support operations with weapons, logistics and sustainment activities.

The ship can hold more than 20 F-35Bs. The Ospreys would be used to carry fuel and or weapons, so that the F-35B can move to the mission and operate in a distributed base. This is what the Marines refer to as shaping distributed STOVL ops for the F-35B within which a sea base is a key lily pad from which the plane could operate or move from.

Alternatively, the F-35B could operate for ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance). Understandably, all US assets area already networked through satellites.

The other new onboard asset is Sikorsky’s CH-53K, which will be backbone for an airborne amphibious strike force. It will be able to carry three times the load external to itself than can a CH-53E and has many operational improvements, such as a fly-by-wire system.

These elements constitute a true enabler for a 21st century amphibious assault force.

CVN-78: Redefining the Large-Deck Carrier

The coming of the USS Gerald R. Ford sets in motion a very different type of large-deck carrier. The hull form of the Ford is a tribute to the very successful Nimitz-class hull design. But that is where the comparisons end.

In effect, the new nuclear-powered carrier provides infrastructure for – significantly – the US Navy as well as its coalition forces.

It is designed to operate more effectively with an evolving air wing over its 50-year life span. The high increase in electric power generation, three times greater than Nimitz, is designed to allow the electronic systems associated with defense, attack and C2 to grow over time.

The carrier’s new launch and recovery systems (EMALS – Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System and AAG- Advanced Arresting Gear), the weapons handling system and many other improvements are visible signs of new capabilities.

The onboard super computers manage everything from electric power to fire power, and give outstanding support to the crew. Laser weapons will be a reality on Gerald Ford.

The next generation in active sensor technology, with great bandwidth in the dual band radars, provides a solid foundation, not simply for the organic defence and strike capability of the carrier but for the entire battle fleet.

In a recent interview Captain John Meier, the designated skipper of CVN-78, highlighted a number of innovations, two of which are the new launch system and the second is the new weaponisation systems and pit stop approach to operating aircraft.

The first involves the shift from steam catapults to an electronic system or EMALS. “The EMALS system will allow us to provide for an ability to launch aircraft more smoothly and with less wear and tear on the airplanes and the pilots. Coupled with the new advanced arresting gear, we will be able to launch and recover a variety of types of aircraft, including future designs that haven’t been developed.”

As for directed energy systems, he observed: “You have a great capacity for diversity of weapons, and the advanced weapon elevators themselves are located on the ship to facilitate faster movement and loading of the weapons.

That’s the underlying principle of the advanced weapon elevators. They carry more weight and they go faster, twice the speed and twice the weight essentially of the legacy weapons elevators” bringing ordnance right near an aircraft for loading.

Combat jets will be loaded in “pit stops” aboard the deck and then launched from the EMALS system.

And with the coming of the F-35 C, the head of Naval Air Warfare, Rear Admiral Manazir noted in an interview done after the visit to the Ford:

“Reach not range is a key aspect of looking at the carrier air wing and its ability to work with joint and coalition forces.

This is clearly enhanced with the F-35.The carrier has a core ability to operate organically but its real impact comes from its synergy with the joint and coalition force, which will only go up as the global F-35 fleet emerges.

And this will get better with the coming of the USS Ford. What the Ford does is it optimises the things that we think are the most important.”

HMS Queen Elizabeth: Reinventing the Large Deck Carrier

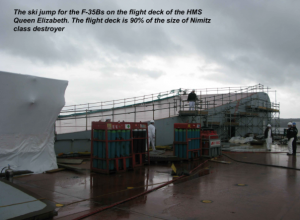

The Brits invented carrier warfare; and in many ways with their new 65,000-ton carrier they are reinventing the large deck carrier and providing something of a hybrid between the USS America and CVN-78.

The flight deck is impressive and is about 90 per cent of the size of the Nimitz class and has a very wide deck.

When I stood at the end of the ski jump and looked down at the flight deck, its width was significant.

And I learned that the flight deck was built by Laird Shipbuilding (unfortunately no relation!).

This ship is designed to operate F-35Bs, which means that the RAF (Royal Air Force) and RN (Royal Navy) will drive every bit of innovation out of the aircraft to provide C2, ISR and strike capabilities.

There will be natural interoperability between the US and British forces, right from training to operations.

Walking the ship takes time, but several innovations one sees aboard the Ford can be found aboard the HMS Queen Elizabeth: significant energy generation, significant C2 capabilities, very large rooms for reconfigurable C2 suites for operations across the ROMO, as well as well designed work areas for the F-35B crews which will handle the operations and data generated by the F-35 to the fleet.

It is a ship designed to transform both the RAF and the RN for it will integrate significantly with the surface and subsurface fleet and the land-based air for the RAF.

To take an example, with RAF jets operating from Cyprus or in the Middle East, the HMS Queen Elizabeth can mesh its air assets with the land based assets and the command centre directing the air operations could be on the ship, on land at an operating base, or in the air, even in the new tankers.

Conclusion

Despite the critics, new carriers are being designed and built to work more effectively in an integrated operational space to provide both defence and offence to a joint and coalition force.

They are key elements of the distributed force, one which is forging a 21st century approach to offense-defense enterprise across the spectrum of military operations.

The author would like to thank Ed Timperlake for his contribution to the thinking underlying this article