By Robbin Laird

To ensure enhanced survivability, the ADF is looking to more effectively distribute over Australian territory. But this makes logistical support for distributed forces a major strategic challenge. And with the changing threat calculus, the force needs to have greater endurance which requires enhanced sustainability.

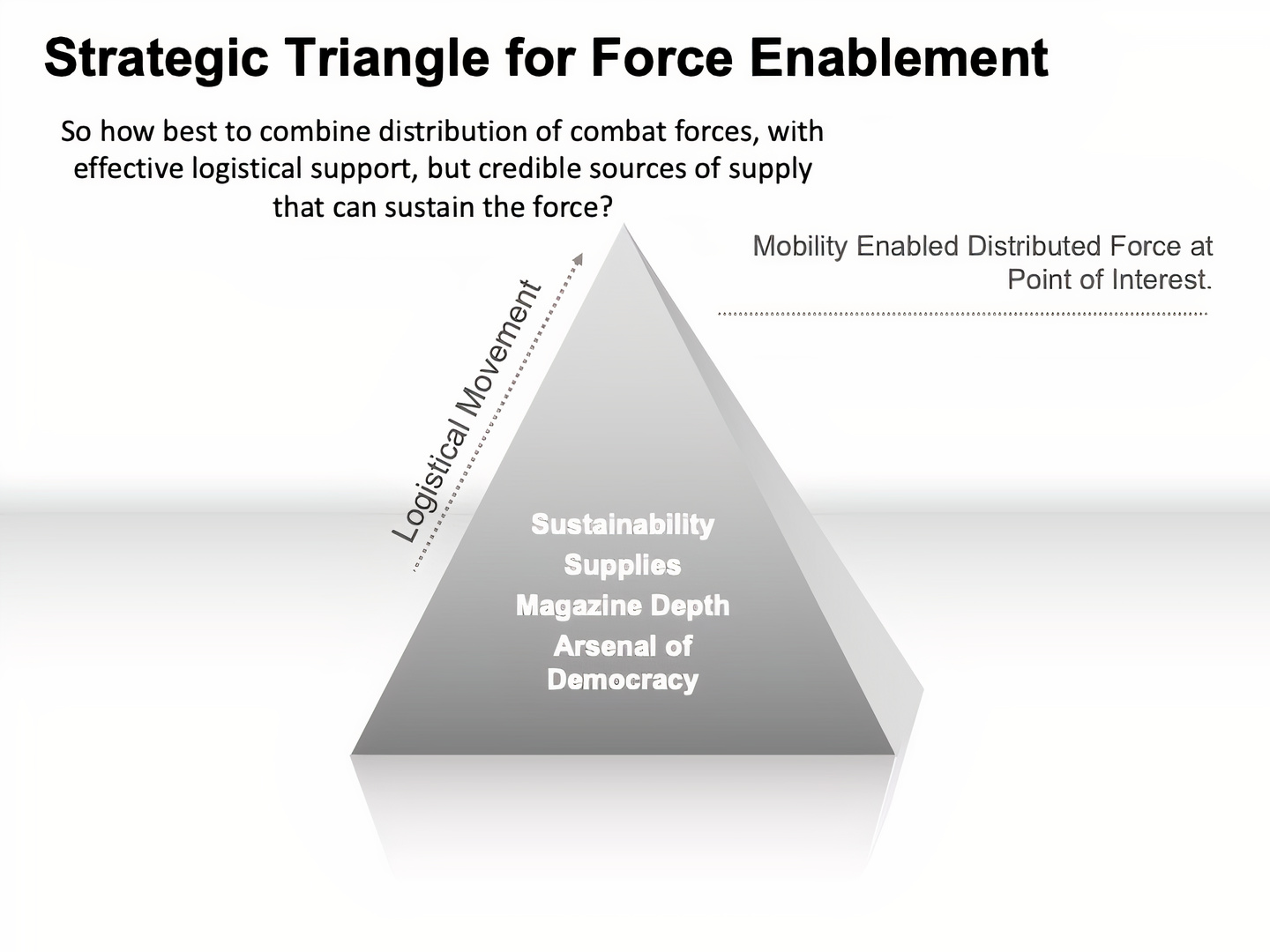

So how best to combine distribution of combat forces, with effective logistical support, but have credible sources of supply that can sustain the force?

In many ways this poses a significant strategic triangle which has to be built and operated in the period ahead to have an effective ADF and, of course, the ADF is not alone in terms of meeting this challenge. Most notability, its major warfighting ally in the Pacific, the United States, faces the tyranny of the Pacific in dealing with this strategic matrix.

During my trip to Australia in March-April 2023, I discussed this challenge with Colonel David Beaumont of the Australian Army, who has worked on logistics issues his entire service life. Currently, he is Director of Joint Professional Military Education at the Australian Defence College located in Canberra.

As Beaumont characterized the challenge: “Sustainment and logistics capabilities determine the endurance of your force. They shape the ability of your force to remain operable. They determine how your force can sequence its operations and operate at the tip of the spear. It can be described as the arbiter of opportunity to paraphrase Thomas Kane. By that I mean, it determines when the force can and cannot act.”

We are experiencing a major shift from just-in time wars and just-in time delivery systems to facing the challenge of response to crises created by adversaries which will challenge our ability to act, to endure and prevail.

As Beaumont put it: “We have been used to certain ways of operating of the past 20 years or so. “We have operated in surges and cycles that have been well planned in advance and shaped our routines. Forces have been allocated on the basis of what we can reasonably sustain. For a country like Australia, we have been able to choose judiciously the forces we can operate with because we know we can sustain them at the right moment and with the right resources.”

The challenge now is to prepare for a different scale and intensity of conflict which simply does not comply with limited sustainability and just-in time logistics. Beaumont added: “We will need now to operate at the maximum of our potential and that requires logistics resources and sustainability planning to suit.”

We turned to the real challenge of getting procurement systems in Australia or the United States to be able to prioritize sustainment and logistics as a strategic issue rather than a residual one.

Beaumont argued that Western military acquisition systems have for a long time prioritized platform acquisition over operational sustainability and preparedness, with corporate success often defined be the perceived effectiveness of platform delivery programs. This emphasis means that moneys tend to be drawn from sustainment or logistics budgets to pay for new platforms or cost over runs of platform programs.

How then does one change this culture and focus?

Beaumont noted that one way to do so that is being started in Australia is to deal with a specific commodities capability needs to be dealt with as a program in its own right, such as the newly launched guided weapons program. It is also important to go beyond headline logistics deficiencies and resolving broader sustainment gaps across the force.

When one considers the problem of mobilization of resources from the general economy, it is easier to conceptualize rather do or fund. If Australia wishes to pursue greater self-reliance in stocks, then mobilization is an inevitable subject which needs to become real in terms of programmatics and funding.

There is the question of enhancing production with allies in order to have an allied-wide approach to production in a new arsenal of democracy model. But the challenge remains for each of the countries involved in joint production or acquisition of stocks available in times of crisis to the national forces.

Then there is the question of logistical means to move stocks to forces which themselves are working the art of force mobility. My interview with the Air Commander Australia highlighted his concern with an enhanced ability for air mobility from diverse locations in Australia. But how to move the parts and supplies necessary to support such an agile operating RAAF?

The blunt fact is that Australia cannot act as if the United States is the arsenal of democracy. The U.S. has reduced its defense industrial base dramatically over the years, as well as its industrial base. Australia is simply not an industrial country. One can NOT assume that mobilization of supply will be a simple switch turning exercise. In today’s world, it has to be built and funded. This is not an easy task nor one that is politically popular as well.

And with a large territory, how will Australia produce, stockpile and move the supplies necessary for itself and allies who are using Australian territory? This requires an effective national and allied interoperable IT system for logistics enterprise management as well as the ability to use maritime, rail, or road systems to move supplies to the point of need.

In short, force mobility, sustainability and logistics have become a strategic triangle shaping the capability for force endurance, effectiveness and relevance to conflict with the authoritarian powers in the 21st century.

Colonel David Beaumont

Colonel David Beaumont is a Director of Joint Professional Military Education at the Australian Defence College, in which he supports the development of the joint military education curriculum for the Australian Defence Force. He publishes widely on strategy and strategic policy, military preparedness, logistics, mobilisation and whole-of-nation responses to crises.

David is a military logistician by background, and has s served in East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan as part of Australian and multi-lateral military commitments. David’s recent position in the Army was as Director of the Australian Army Research Centre, and until July 2022 was responsible to the Chief of Army for many of the Army’s research partnerships with domestic and international academia and research-institute, as well as the development of bespoke research projects and programs.

David researches, writes and presents about strategic policy, logistics, military capability development, and the involvement of the ‘whole-of-nation’ in defence and national security. He commenced doctoral research at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, in 2016; David’s research is examining the interaction between the ‘national support base’ and Defence in the 1980’s and 1990’s to support military preparedness. He manages, edits and writes to an international audience at the blog ‘Logistics in War’ (www.logisticsinwar.com) and other online venues. His last major paper was 2020’s ‘An uncertain and dangerous decade’ which examines the coming decade as characterised by strategic competition, post-pandemic crisis responses and new roles and tasks for the ADF.

David’s academic qualifications include a Bachelor of Arts (History and Politics) and Master of Business (Strategy) from the University of New South Wales, and a Master of Arts (Military Studies) by research from the Australian National University.