The Hon. Ed Timperlake on the role of power projection forces in supporting U.S. obligations and interests when effecting a strategic withdrawal.

Amphibious Assault Vehicles with AAV platoon, Battalion Landing Team 1/7, 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit,

Amphibious Assault Vehicles with AAV platoon, Battalion Landing Team 1/7, 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit,

maneuver toward the USS Denver off the coast of Okinawa, Japan, Sept. 7, 2010

(Credit: http://www.marines.mil/unit/31stmeu/pages/photos.aspx?Page=11)

10/15/2010 – It was said that when the last Marine F-4 on August 15th, 1973 pulled off target and after dropping the last bombs to stop the Khmer Rouge from taking over Cambodia, the call went out: “That’s it: see you next war.”

Tragically, the “next war” was executing on of the most difficult of military operations in the tactical handbook: evacuating forces out of combat. It was specifically tragic because the U.S. Congress cut off all funds in 1975 to support the South Vietnamese in their attempt to roll back a 17 Division invasion from the North. Once Congress said not to any more funds, the fall of South Vietnam became inevitable.

It was not a military defeat as much as a political defeat and that is how a democracy can and does work.

Previously, the North Vietnamese had tried to invade the south in the famous Easter Offensive of 1972. It became a huge mistake and military setback for the NVA Army, because USAF, USN and USMC air power decimated their attack. But by 1975, Congress had stopped the use of any U.S. air in providing offensive support missions for the South Vietnamese regime.

North Vietnamese T59 tank captured by South Vietnamese 20th Tank Regiment,

North Vietnamese T59 tank captured by South Vietnamese 20th Tank Regiment,

south of Dong Ha, Quang Tri province, Vietnam, during the 1972 Easter Offensive

(Credit: http://www.olive-drab.com/od_history_vietnam_easter1972.php)

Consequently, during the last days of Saigon, Marine unites arriving from the sea could only arrange to help as many Vietnamese as possible evacuate to the sea. Boat people and the Cambodian holocaust were yet to come as the U.S. was making an attempt in April 1975 to rescue those Vietnamese we had a debt of honor to pay. Sadly that debt was not fully repaid.

When most military authors write about amphibious operations they do not focus at all on the “withdrawal” dynamic, and certainly with no consideration of coalition engagement and “leave-behind” obligations to support allies shaped within engagement operations.

Normally, analysts of amphibious operations tend to focus on the offensive or the insertion of force. Some describe historical failures such as Gallipoli, Zeebrugge and Dieppe. While the majority go into great detail appropriately describing unbelievable courage and, at times, costly success, Guadalcanal, and all USMC island hoping campaigns in the Pacific and USMC landing at Inchon in the Korean war are excellent historical examples.

In the World War II European Theater, the U.S. Army, British, Canadians, Free French and other allies liberated a continent from Nazi tyranny starting with one of the most successful amphibious operations in history at Normandy.

Offensive operations from the Sea are complex and dangerous, because you literally begin with one Marine or Trooper and build from that person. “Defensive” operations are even more complex and dangerous because your forces are declining as you withdraw, not building up for insertion.

Historically, “the Miracle at Dunkirk” is often looked at as the epic operation to evacuate a force to the sea while under fire. The saving of the British Army be Royal Navy and civilian ships was a key building block for the eventual return to Europe and to the defeat of the Nazis. Dunkirk would not have been possible without two elements coming together: sealift and air superiority provided by the RAF over the withdrawal area.

As mentioned before, Inchon is considered an historic event in successful USMC amphibious operations. But what needs also to be considered is what occurred after the famous breakout to the sea from the “Frozen Chosen” Reservoir in what is now still North Korea.

The 1st Marine Division was surrounded and outnumbered by six battle hardened Chinese Divisions and they successfully fought their way to Hungnam Harbor. Protected by Naval gunfire and thanks to the USAF engaging in MIG Alley, the Marines were successfully pulled out. As a nice touch, they left blowing up the harbor.

Then the next generation of Marines was called into as Saigon was falling to provide a withdrawal to the sea. Navy/Marine amphibious forces, once again under an air umbrella, saved thousands of Vietnamese.

Bottom line: what can go in from the Sea with a Navy/Marine AF team can also be withdrawn. Allies to whom we owe a debt can be evacuated or protected from the sea.

These possibilities remain important for our current global commitments and operations. And with the 21st century con-ops provided by the MV-22, the Harrier and then the F-35B, the Marines can engage in providing capabilities for such situations.

The U.S. Naval Institute in an excellent and timely narrative on recent USN and USMC anti-piracy operations describes three concurrent activities by a Marine expeditionary Unit.

The Navy and USMC team recaptured a ship, while also conducting combat operations in a war and concurrently providing humanitarian relief. It would be hard to find a better value investment for global operations than such combined and flexible capabilities.

A number of key lessons learned should therefore guide our judgments about some key desired elements for the evolution of future power projection capabilities.

The current U.S. Congress and Administration, notably Secretary Gates, are publically discussing the future of the USMC. Aided and abetted by ignorance of some writing in the media (a recent Newsweek piece comes to mind), the entire concept of USN/USMC amphibious forces is being challenged. And, in the UK deliberations on the future of their forces, a key target are amphibious forces.

The challenge comes in two forms. One is an assertion of strategic vulnerability and, hence, irrelevance, and the second, a result of congruent drawdowns and cuts.

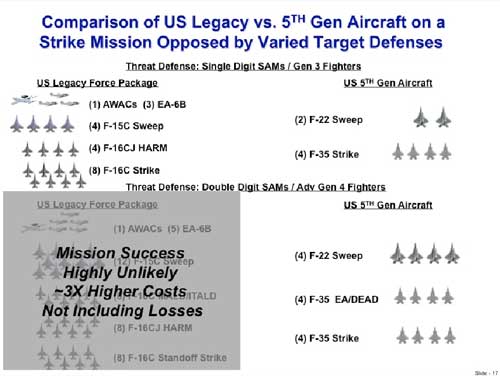

First, there are those who argue that enemy capabilities are becoming so deadly that U.S. forces afloat might be considered “wasting assets.” This claim which is rarely contested needs to be addressed and will be addressed in a future column.

The second challenge is a result of the confluence of several Administration initiatives: the drawdown in Iraq, the proposed post-surge withdrawal from Afghanistan and a significant cut in the US air and naval force structures.

The second challenge ignores the residual engagement of withdrawing force and the continuing obligations to allies forged for many years of operations. There is a never forgotten moral obligation the U.S. owes to those Iraqi and Afghan forces and citizens that trusted and supported the U.S. and its coalition partners during a decade of combat engagements.

Once the US and its allies draw down ground combat elements, air power can help keep the fanatical killers at bay to some extent. But ultimately, air power only goes so far. We owe it to our Iraqi and Afghan allied forces and their Nation’s civilians to have available in close proximity a rapid reaction force. Such a force needs to combine combat and humanitarian relief in a 21st century hybrid insertion of boots on the ground in all rugged terrain, which is a hallmark of the evolving capabilities of the amphib force.

Since we are getting ready to drawdown in Iraq and to leave Afghanistan, what about those villagers and people in enclaves that trust us? A MEU is a 9/11 force in readiness that can make sure that we can demonstrate that we have not forgotten the Vietnam result or the Cambodian Holocaust.

Insertion of an offshore MEU to defend a village or evacuate threatened allies to safe havens is a lasting debt. And this obligation becomes part of our staying power in a region, which will remain central to the U.S. even after significant removal of ground forces. The MEU allows us to have available a combat blocking force on the ground as an enemy begins to mass and concentrate forces and have a lift as necessary to relocate them to safe havens.

A MEU backed by a Carrier Battle Group (CBG) can easily bring enough firepower and Marines on the ground and lift so innocents are not massacred. This debt of honor backed by an ever ready Navy/Marines afloat and AF Air Power on station can and should last as a key element of the regional calculation.

The next Congress should view a strong and agile military power projection force of a MEU, CBG and expeditionary USAF assets as a legacy force for good. U.S. power projection in the Gulf can and will save lives and demonstrate the presence of tools to support friendly forces and elements in the region.

If not, we would see once gain an old cliché coming into play: even worse than being America’s enemy is being our ally in an unpopular war.