As part of the Trade Media briefing in Spain in May 2010, a senior representative for Airbus Military provided an overview of different approaches to services which, we thought, would be very useful for readers of SLD, notably as the US debates the future of programs such as performance-based logistics. Richard Thompson, Senior Vice President for customer services also provided an understanding of where the current Airbus Military business efforts fit within these conceptual approaches.

[slidepress gallery=’crafting-a-services-approach-a-perspective-from-airbus-military’]

Different Approaches to Services

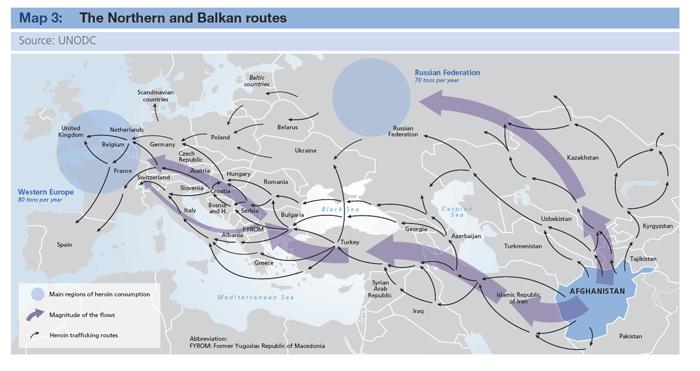

In terms of concepts that we are developing, we’re moving from what has been for the last year’s traditional product support, all the usual things that you associate with a traditional product support—the MRO, the technical support, the technical publications, configuration management, continuous air worthiness support for the fleet, training services, spares and material support—we also are moving into helping our customers with urgent operational requirements, modifications, upgrades, role changes of aircraft once they are in service, et cetera—those kind of support services, and what we called our FISS, which is the Full In-Service support concept, which is effectively a performance-based logistic support service on a power by the hour type—on a flight/hour service type arrangement, where we wrap up a whole series of services into a single contract that guarantees the support the customer requires over a period of years, and he pays accordingly to the number of flight hours that he flies.

Moving on to what we call Integrated Mission Support Services, …. we add other services which get a lot closer to the actual operation of the customer, where we actually help the customer in delivering his mission and operating his aircraft.

And that’s where we can climb in the value-chain and access new sources of funding. And, again, win/win situation: customer is happy—he can concentrate in actually flying his mission in doing what he does best, his core activity; and we increasingly fill in other services that traditionally have been the role of customers, but which they are increasingly outsourcing.

Typical example of that, the “jewel in the crown,” if you like, of that type of service provision is, of course, the FSTA contract in United Kingdom, where the customer doesn’t even own the assets. He doesn’t own anything…..

And quite apart from the fact that it is a PFI, that’s almost immaterial; it’s how the service is delivered at the end of the day, and that’s, of course, the prime responsibility of Air Tanker Services, but we are just behind them in that concept. But that concept, of course, is a very large and very complex affair, but it doesn’t have to be, of course. But the concept itself can be exported to other type of solutions, and that’s what we’re currently engaged in talking to some of our smaller customers that did not have the wherewithal or the infrastructure to provide and maintain fleets operating, how we can actually step into those shoes and do that for them. And so that what they contract for, in fact, is mission success.

The traditional support, where we have about 60% of the revenue is indeed in material support—the supply chain. And it’s not just proprietary parts in our business; it’s vendor material as well from our suppliers.

And the beauty is that, of course, we are a one-stop shop; customers come to us and they don’t have to deal with myriad of suppliers. They know that we hold the stocks, that we can provide them the rapid turnarounds and the sort of support that they need. But 40% of that traditional support usually in terms of revenue is things other than material support: technical support, engineering and training services.

With the FISS concept, we guarantee the delivery of those elements detailed there to our customers, and we develop key performance indicators with our customers as part of negotiating the contracts with them, and we are measured and paid in accordance to our ability to deliver against those KPIs. And so the idea there is to keep the customer’s fleet flying; the more hours he flies, the more we get paid, the more he flies, the happier he is.

And finally, the concept of integrated mission support services, where the customer is effectively contracting for availability and mission success. And the idea here is that we try to be as flexible as we possibly can in meeting our customers requirements.

The idea behind the FISS contract, of course, is the customer can budget a lot better over a number of years, and we take into account using some fairly sophisticated tools what the peaks and troughs throughout the life of an aircraft in service will be, and we can average that out and way ahead, for many years in advance, we can actually enter into a formula, whereby the customer will know over a period of years exactly how much he’s got to budget for, in order to keep that fleet of aircraft flying. And that’s the beauty of the concept, as far as the customer is concerned.

As far as we’re concerned, we are guaranteed long-term support for a customer and we can budget ourselves and invest ourselves and plan in the long term.

…. So, the advantages, obviously: fixed budgeting, no risk, no need to come back and worry about repeat contracts for spares and repairs on a per-even item, which is usually quite complicated and you haven’t got time, when you need something, to start entering into terms and conditions of how it might be done. Stock-levels are optimized to a fleet usage, contract obviously has guarantees in it: the customer knows that if we don’t perform, he has a contractual tool in his hand that enables him to take action against us and force us to perform. We flow those terms down, obviously, into our supply base, so the risks are shared, and everybody’s incentivized and motivated to deliver best support. The maintenance program, of course, is put in place from the very beginning that monitors and continuously monitors the fleet so that we get feedback from our customers, as well, on a continuous basis, so that we can refine those models and our predictive models get better all the time. We can optimize our maintenance models that way, and the customer can focus, then, on, what is its core activity, which is the mission success, and we fill in the rest.

Examples of the Military Airbus Effort

We’re getting ready, we’re ramping up to deliver the first of the MRTT’s, the KC30A to Australia, our launch customer, and I’ve recently just come back from Brisbane and the RAAF base there in Amberley and the facilities are looking good. They’re all ready to go—33 squadron all geared up anxiously waiting for the first plane to arrive and they’re all fired up. The DMO people who are at the base who represent the customer, the end user, 33 squadron and Qantas Defense Services with whom a couple of weeks ago we signed the contract which is effectively a through-life support agreement for the next 22 years. QDS will be the prime contractor delivering that through-life support in front of the customer. They have their offices there in Amberley as well and they’re all ready to go and we will be supporting them locally in Australia through our subsidiary, Australian Aerospace, who will be doing some specific work packages on behalf of QDS and also remotely back from here in Madrid with all our technical support and other services that we will provide QDS.

We’ve hit a major, major milestone in the sense that we’ve actually started delivering some real hardware to the Australian Airforce—the first piece of hardware that we’ve actually delivered, the first of some 500 pieces of support—ground support and test equipment, and the first of some 4,000 spare items that we will be delivering to the Commonwealth over the next few months. It’s a complex process but we’ve put it to the test, we’ve done the first deliveries and it all works. And so, good news, and everybody’s keen, ready to go.

We will also be placing there—there will be a total of six field reps, of which two will be ours. We will be placing those two field reps at Amberley over a three year period to ensure a smooth entry into service.

So that’s MRTT for Australia, equally, obviously not the same degree of progress or advancement, because Australia is our first customer, but we have met all contractual milestones of the two primary subcontracts that we have with Air Tanker Services in the UK. We’re obviously principle share-holder as you know, of Air Tanker Services. The two primary subcontracts, which we are responsible for are for the green aircraft and the supplementary type certificate elements of the military conversion, and we are up to speed and ramping up there as well, in terms of supporting that entry into service. ITS, as most of you know, on FSTA is in September of 2011. Also, advanced planning is in place to support the entry to service of the Royal Saudi Airforce and the UAE MRTT as well.

A400Ms—A400M is a bit further away, obviously, but the magnitude of the task ahead and the number of things that we have to get ready with the first customer, the French Air Force and the United Kingdom joining France in a joint approach to contracting for in-service support. They are the first customers and a lot of activity at the moment going on in terms of building the bricks that we’re then going to use to put together in different ways, different combinations, the basic elements of in-service support for our different customers. And as I said, the first ones there are France and the UK. It’ll be a single, joint contract. Obviously they will have different timetables and milestones inside those contracts to take account of the actual different entry into service dates between the French Air Force and the Royal Air Force. But the elements will be very similar, and the concept, the philosophy behind the in-service support will be very similar for both nations.

Global presence around the world—we have in all of those countries shown and in fact in other places, either service centers, field representatives of customer support representatives providing our customers around the world with the contact point—first point of contact—entry into our customer and the reach-back into our organizations here in Madrid to support our customers around the world…..

And some relevant figures on a per-year basis, taking last year as an example, some 40 aircraft came through our maintenance facilities, either our MRO operation in San Pablo in Seville, or maintenance centers around the world. In terms of component repair management, some 3,800 customer repair orders, and we subcontract to some 120 repair centers around the world. Request for quotations and line items, over 3,000 and 46,000 line items.

And in terms of turning those into purchase orders, we actually received some 3,000 purchase orders covering some 40,000 line items. In terms of warehouse movements, some 42,000 delivery line items last year. In terms of AOG—that’s material AOG—that’s when an aircraft is on the ground for lack of a spare part, and the customer needs a rapid response—some 1,700 requests from around the world. Ands 98% of those were delivered within 24 hours.

And that covers just—not only proprietary parts, as I mentioned, but also vendor items from all of our supply base. Some 1,825 hours of course-ware were developed. That was not just the period of last year. That was the period up to 2008. But last year we cycled some 400 students through our training center in Seville. And in terms of technical publications—yes, unfortunately, many of our customers still require us to deliver printed technical publications—some 3,800,000 pages, but also increasingly moving to electronic media with our tech pubs as well. And, of course, in the case of the A400M, it’ll be all electronic, no paper at all.

———–

*** Posted on June 29th, 2010