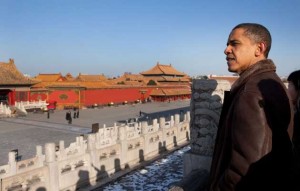

As President Obama began his Asian journey, his White House aides said he viewed China as “America’s most vital partner in tackling the globe’s most intractable issues.” The President himself said “We meet at a time when the relationship between the United States and China has never been more important to our collective future.” His words suggest that Asia is the new focus of US economic and security policy. To rephrase Donald Rumsfeld’s dismissal of Continental Europe as “Old Europe,” this sounds like Obama’s dismissal of Europe as “The Old World,” and embracing China-centric Asia as “The World of the Future?”

Chinese Communist Party leaders were no doubt happy to receive such US recognition. This is a dicey time for Chinese leaders, confronted with growing unemployment and social unrest made much worse by last year’s collapse of the Chinese export engine. The Olympics were supposed to be the “biggest ever coming out party.” In retrospect, there is risk that history may judge the 2008 Olympics to have been the “biggest going away party” ever.

China’s economy has long been driven by external demand, with exports constituting two-fifths of GDP. When export orders literally vanished more than a year ago, the economy ground to a halt. The Chinese government issued artfully deceptive figures which suggested that China’s economic growth had merely slowed to a 6 or 7 percent annual growth rate, and much of the world press naively accepted these numbers. It was not until much later this year that the leadership reluctantly admitted that growth in the final quarter of 2008 figures had actually fallen to zero, and only a little more than zero in the first quarter of 2009. Political leaders had no choice but to initiate massive economic stimulus: roughly $600 billion in fiscal stimulus and $1.4 trillion in new, politically mandated bank lending. That’s a $2 trillion stimulus – more than half China’s total GDP. Yes, the economy gives the appearance of regaining momentum, but most of the recent rebound has been levitated by government spending and a huge expansion of bank loans ordered by the Communist Party leadership.

By late 2009, Chinese authorities claim that GDP rate of growth is back to near double digits. Markets around the world gleefully concluded that China had successfully “decoupled” from the US engine of growth and would now help lead the world out of the deepest, longest recession since the 1930s. Yet these astonishingly robust calculations seemed somehow inconsistent with internal data. For example, auto sales inside China are said to have grown by nearly 80 percent this year – yet sales of gasoline have remained flat. Have the Chinese invented miraculously fuel-efficient engines? Or are most of these vehicles parked in storage at state owned enterprises? Where did the purchasing power come from as unemployment soared? Most likely from bank loans, without any concern for credit worthiness of borrowers. This was a uniquely Chinese version of the infamous “no documentation” home mortgage loans that led to the collapse of subprime lending in the US.

Chinese economic statistics eerily remind us of the overoptimistic figures that continuously flowed from Gosplan in the days before the Soviet Union collapsed. Consider reports of ever-growing Chinese imports of coal, iron ore, and copper during the global economic downturn. When imports of raw materials regained upward momentum, market analysts in New York concluded that the Chinese economy was humming again. Yet, electrical energy consumption in China grew only slowly, suggesting that manufacturing remained near standstill. What happened was that Chinese companies could easily get large loans, but there was no demand for their export-oriented manufacturing output. Instead of restarting their manufacturing plants, government loans were used to stockpile huge quantities of raw materials sourced from other countries. Stockpiling was encouraged by Party leaders who bet on a V-shaped recovery in the world economy, early rebound in Chinese exports, and return of world inflation. By using stockpiles to get a head start, this also presented an opportunity for China to corner world supplies of rare earth metals and other key commodities, to give Chinese enterprises pricing power in global competition.

In recent years China’s economy thrived by relaxing central government control. The huge, new lending binge mandated by Party leaders in 2009 enabled large state owned enterprises to gobble up smaller, innovative, successful firms. Thus, the Party stimulus measures are effectively helping to recentralize the economy, making it less resilient in meeting rapidly changing world market dynamics.

Many analysts still see China as the rising hub of global manufacturing after the current world recession fades. This characterization of China is not consistent with what many global corporations have learned from hard lessons in China: Official wage hikes and mandated unionization of foreign enterprises have made China’s labor far less competitive. Quality control is difficult to achieve and almost impossible to sustain in Chinese manufacturing operations. Bringing to China advanced technology opens the way for Chinese technology piracy and cloning of foreign products and production facilities. Increasingly, Japanese, European, and US companies see some opportunity for production inside China for sale to Chinese consumers, but have fading appetite for using China as a production base to serve the rest of the world.

Most important, China’s decision makers seem fixated on a return to the boom years before the world financial crises of 2007 and 2008, and before the current world recession. For the last 50 years, world trade grew at roughly twice the rate of growth of world GDP. China grabbed onto this hurtling momentum and built its economy and its currency policy accordingly. Looking forward, the hard reality is that world economic growth will most likely be sluggish for the next few years, as unemployment rises in the US, EU, and many emerging market economies. China is not the only export-dependent economy. A wide range of advanced (e.g., Germany and Japan) and emerging market economies were enabled to grow fast in recent decades by hitching on to strong growth in world trade, with the US consumers constituting the primary source of momentum. With high and rising unemployment, no growth in personal income, credit contraction, decimated household wealth, and rising debt service obligations, American consumers are likely to spend less and save more for the next several years. Confronted with huge deficits over the next ten years or more, the US Government will not be able to compensate for slow consumption with dramatic increases in government spending. The world will have to get used to slower US growth, which in turn will mean slower growth in world trade. Subdued economic growth in the US means anemic economic performance for all the export-dependent economies around the world. The recent collapse of world trade also means that the world will continue to experience industrial overcapacity for several years ahead. This will like result in a slowdown in foreign direct investment in many of the emerging markets.

In other words, China is not about to “eat our lunch.” The present Chinese leadership will continue its struggle to choose new Party leadership in 2012, with underlying domestic economic weakness roiling the succession process. As in many other countries, incumbent leaders will face challenges to their own political survival. Domestically generated demand will be needed to replace robust export demand, but a transition to domestic-led growth will take years. The Chinese government will face bad choices of either pricking the growing stock market and real estate bubbles which have been made bigger by limitless lending, or let the bubbles burst by themselves, and try to cope with a financial crash and capital flight from China. Party leaders will also be challenged by an aging society, with shrinking numbers of young people supporting a growing array of elders. As has been remarked, “China will most likely grow very old long before it becomes very rich.”

When President Obama visited China, it was not clear what his agenda was. He wanted to demonstrate greater US interest in Asia, and build personal relationships, but he did not seem to come with a strategy for economic and security engagement. He did complain about Chinese currency policy, but without making that a core issue. To the Chinese, advised by sophisticated Washington lobbyists, President Obama looked vulnerable to Chinese counterpunches. The Chinese, sensing that the world’s recession is far from over, chose to take the offensive and criticize US fiscal and monetary policy as reckless in its encouragement of a weakening of the dollar and growing bubbles in stocks, commodities and oil. It could be said that instead of climbing the Great Wall of China, President Obama hit that wall.

What Chinese policy makers fear most at this time, close to the end of 2009, is that the US economy will not rebound vigorously, leaving China and other export-dependent economies struggling. Behind the curtain, they also share the growing world market apprehension that stock markets, commodities, and oil are “bubbly” and that a serious negative correction, or even a broad market crash may loom ahead. If bad things happen to world markets, better to be seen blaming US leadership than to acknowledge that Chinese policies were mistaken.

Of course, President Obama’s Asian journey included other destinations. In Singapore, he met with all 10 ASEAN leaders, and with the wider 21-nation APEC group which met to discuss greater cooperation. He agreed to increase US collaboration with ASEAN in exploration of regional economic integration efforts. In South Korea, President Obama put emphasis on seeking resolution of the nuclear power challenge of North Korea, but he also surprised observers by offering to “reexamine” the US-South Korea FTA which had long lain dormant in Congress. To avoid confrontation, the South Korean President also expressed willingness to have another look at the FTA, even though his predecessor warned that any changes were non-negotiable. In reality, this was political theater on both sides. Neither the Congress nor the South Korean legislature is ready to consider a re-negotiated bilateral FTA agreement.

In Japan, President Obama and his team sought opportunity to establish a more intimate relationship with Japan’s newly elected government, but his counterparts in Tokyo had no experience in governance or in managing economic and security affairs. Japanese voters had not given a policy mandate to the newly elected DPJ – rather, they had simply vote to kick out what they believed to be a failed LDP ruling party, ending its decades-long domination of Japanese politics. Today’s DPJ Diet majority is even more divided about policy choices than the Democrats in the US Congress. There is no core leadership consensus about what to do about recession and deflation, or Japan’s exploding government debt relative to GDP (soon to exceed 250 percent of GDP), or Japan’s failing social support system for its aging society. The DPJ has no coherent foreign policy either. The new Japanese leadership fears losing the security umbrella of the US, but also fears the looming dark shadow of China, its close neighbor. There is anxiety about how to replace dependence on exports of capital goods and autos with some new growth engine. There is acute apprehension about the unwelcome strength of Japanese currency, which is threatening the sustainability of the corporate sector. Obama had nothing new to suggest, and Japan politicians had little expectation that he would bring anything useful for the DPJ. As for average Japanese people, they have learned to expect little from government during the last two “lost” decades, and have low expectations of any kind of engagement with other nations. The new American President was a public affairs novelty, but there was little belief the visit had any consequence for daily life.

During and after the President’s Asian journey, press and media commentators struggled to identify key themes underlying the trip. Was it just a just a typical “meet and greet” trip? If the President was shifting America’s focus to China and its neighborhood, what did this mean for India? Or for Europe? Or for relations in the Western Hemisphere? Or for the architecture of NATO and overall military security?

In response to the growing array of questions, President Obama tried to explain that is trip was about trade. He said he was seeking ways to encourage increased US exports, to help generate US jobs, through greater engagement with China and the rest of Asia. He warned the Asians that “the US cannot any longer be the consumer of last resort,” and that Asians needed to substitute domestic demand for export driven economic growth.

|

Country |

Total in Billions of US $ | Year to Date Total in Billions of US Dollars |

| Canada | 38.37 | 311.00 |

| China | 33.73 | 259.86 |

| Mexico | 27.74 | 217.51 |

| Japan | 12.98 | 105.04 |

| Germany | 9.38 | 82.16 |

| UK | 8.12 | 68.41 |

| South Korea | 5.95 | 49.40 |

| France | 4.25 | 44.70 |

| Netherlands | 4.25 | 36.10 |

| Brazil | 4.10 | 33.57 |

Top Ten Countries with which the US Trades For the Month of September 2009

The values are for Imports and Exports Added Together

These 10 countries represent 65.20% of US Imports and 62.66% of US exports in goods (Bold added by Sldinfo)

Source: http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/2009pr/09/

This focus on a desire to change the dynamics of trade across the Pacific reveals Obama’s hope that exports can help pull the US out of its economic slump. For any US President, trade is one of those issues over which the President has very limited influence. World trade depends upon global growth, global capital flows, exchange rates, differences in economic capabilities of each nation, etc. World trade began to contract last year – this was the first time there was sustained contraction since the end of WWII. It is still not clear whether trade will start growing again, and at what speed. As for day to day management of imports, the President must yield to US trade laws governing “unfair trade practices” and to past agreements with other governments. This is a realm governed by lobbyists, lawyers, and members of Congress representing trade-sensitive districts.

In Congress, Japan was viewed as the great threat 20 years ago, until the Japanese economic bubble burst at the end of the 1980s. Now, China is perceived as the primary threat to American jobs, and “unfair” Chinese currency policy is viewed as the lever which enables China to “steal” US jobs. While the President might like to stand tough and demand a change in Chinese policy, he must be mindful that the US federal budget deficit is growing rapidly and that the US Government will need to borrow from foreigners to help finance growing debt. He cannot risk confronting the governments of China and Japan, which are the primary creditors of the US.

source: U.S. Department of the Treasury/Federal Reserve Board

November 17, 2009

If the governments of those two nations decided to stop buying US debt and to reduce their present holdings of Treasuries, the President would be confronted with sharply rising US interest rates – threatening to choke off the US economic recovery and ensuring more unemployment.

There is a more basic flaw in President Obama’s focused attention on the promise of trade as a potential generator of new jobs. For the US, exports are a small fraction of GDP. World trade has stopped growing, and may remain subdued for a long time. The only way to increase US exports would be to take market share away from other exporters around the world. That would not only need foreign governments to change their economic policies; it would also need a weaker US dollar. If the dollar continues to fall, then other currencies will have to appreciate even more. The outcome will be collapse of the export sectors of the Eurozone, Japan, and many emerging market countries. This in turn would bring a second and even more powerful tsunami of recession and unemployment throughout the world – with uncertain but negative consequences for US export industries. Moreover, if the world becomes convinced that Obama wants a weaker dollar, then foreign governments and business people will want to dump the dollar and flee to other currencies, or commodities, or gold. The outcome could include much higher oil prices, inflation in raw materials, and much higher interest rates for American business and households – a really evil political and economic brew that would endanger the incumbent President and his majority in Congress.

Exports as a percentage of U.S. GDP

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2009

Now that the trip is over, President Obama will have to spend time reassuring other friends of the US that they still matter. He will have to figure out how to explain to the leaders of India that a strategic partnership is vital as a counterweight to long-term power projection by China. In the meantime, leaders in Berlin will likely take this shift in American attention as yet another justification for intensifying German cooperation with Russia on all matters, regardless of the consequences for the rest of the European nations, especially those in Eastern Europe. The economic dynamics being set in motion by Washington with Asia will likely alter the security dynamics of much of the rest of the world, unless there is a deeper, more complex, secretive strategy behind that is not yet visible. Doubtful – but possible.

***

Harald Malmgren was a key trade official in the Johnson Administration and chief US trade negotiator in the Nixon and Ford Administrations, as well as special advisor to the Senate Finance Committee. He is now strategist for large financial institutions and sovereign wealth funds in Asia, Europe, the Middle East and North America. Dr. Malmgren is a regular contributor to Sldinfo.com.

———-

***Posted November 23rd, 2009