2012-08-16 by Robbin Laird

The Japanese government released its latest Defense White Paper late last month.

This is the first white paper released since they announced their decision to acquire the F-35, and provides a further elucidation upon the new defense policy announced in 2010.

The Japanese announced in that year, that they were shifting from a static island defense, which rested upon mobilization, to a “dynamic defense” which required more agile forces able to operate in the air and maritime regions bordering Japan.

Notably, the Japanese recognized the need for these “dynamic defense” forces to be interoperable with allies to provide for the kind of defense Japan and the allies needed in light of changing dynamics in the region.

As the White Paper puts it:

It is necessary that Japan’s future defense force acquire dynamism to proactively perform various types of operations in order to effectively fulfill the given roles of the defense force without basing on the “Basic Defense Force Concept” that place priority on “the existence of the defense force.”

To this end, the 2010 NDPG calls for the development of “Dynamic Defense Force” that has readiness, mobility, flexibility, sustainability, and versatility, and is reinforced by advanced technology based on the latest trends in the levels of military technology and intelligence capabilities. The concept of this “Dynamic Defense Force” focuses on fulfilling the roles of the defense force through SDF operations.

It is obvious that changes in the neighborhood require Japan to adopt such a policy.

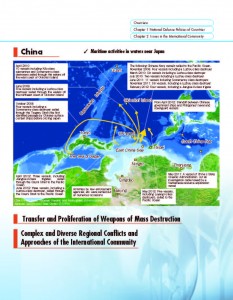

The North Koreans have built and deployed a nuclear tipped missile force, which clearly threatens Japan. And the Chinese are shaping power projection forces to provide for an increasingly capable force able to operate in the maritime and air space affecting Japanese security.

The Chinese game in this regard is especially important to recognize. Although the Chinese leadership has made their intentions quite clear about expanding their military capabilities and regional and global reach, Western powers continue to call for increased “transparency” with regard to Chinese intentions.

“Transparency” is nice, but capabilities to counter any misperceptions by the Chinese are better. And the Japanese White Paper is clear on both. It is important to Japan to work with allies and to work with the Chinese in shaping a more effective and more stable security situation in the neighborhood.

Nonetheless, wishful thinking is just that. Or apparently, they did not require a J-20 flying over the head of their Defense Minister to get this point.

Defense capabilities are Japan’s ultimate guarantee for security, expressing the will and capacity of Japan to defend against foreign invasions. In this way, the function of defense capabilities cannot be substituted by any other method. For this reason, defense capabilities are vital for ensuring an appropriate response to various contingencies arising from the security challenges and destabilizing factors, which are diverse, complex, and intertwined….

Of course, the Chinese play the old Soviet game of accusing responsess to their provocations as unilateral actions taken by whomever responds! It is no surprise that official Chinese sources have cautioned Japan against their analyses in the White Paper and the actions being taken.

The Defense White Paper 2012 has no new contents but repeats the “China military threat theory.” Japan is willful to neglect the over-investment in its national defense, causing the anxiety of its neighboring countries.

From Japan’s dealings with the Diaoyu Islands and other issues we can see that some Japanese still regard their neighbors as enemies. In addition to “concern” over the China, Japan also mentioned North Korea enhancing their capability of ballistic missiles in the Defense White Paper, again claiming its sovereignty over the disputed islands with Russia and South Korea. Japan has shown its distrust of surrounding countries in the Defense White Paper, so how can it keep good relations with them?

The Defense White Paper directly linked Japan’s security with the U.S.-Japan alliance, exposing Japan’s thoughts that it will have nothing to fear if it can rely on the U.S.-Japan alliance and win over South Korea and Australia. Although Japan has been maintaining a consistent strategy with the United States, it is impossible that the United States will stand by Japan and become the enemy of the East Asian countries. Some U.S. analysts said that through stressing the U.S.-Japan alliance, Japan tries to use the United States’ return to Asia-Pacific region to realize the goal of an independent military. In this regard, the United States should make early prevention.

At present, Japan has a gloomy economic and financial situation and so rendering the surrounding threats can provide reasons for increase in defense expenditures. The tough talks of the neighbors are more likely to become an excuse for Japan to promote revising the pacifist constitution and achieve a breakthrough in dispatching self-defense forces.

Regarding Japan’s Defense White Paper, South Korean media outlets said that the Japanese militarism eradicated after the World War II seems to be resurrected, and France and European media commented that the international community needs to prepare for Japan’s use of force for defense. Japan’s defense papers in recent years always include the Cold War mentality, the right-wing thought and the mentality of fear of China. China and Japan had gotten along well with each other and they also had warfare and confrontation. Recently, the extreme right-wing ideology of some Japanese right-wingers is very alarming.

The Japanese are a critical element of any new Pacific strategy for the 21st century.

From an American point of view, they are the vortex of two strategic geometries: a strategic triangle which reaches from Hawaii to Guam to Japan and provides the vectors whereby the United States can provide and air and maritime power to assist in the defense of Japan and deterrence of powers in the region.

The other key strategic geometry is a quadrangle from Japan, to South Korea, to Singapore to Australia within which greater interoperability of forces and ability to re-enforce one another will be an essential element of shaping deterrent and operational capabilities in the Western Pacific.

And the intersection of the two geometries, supported by reachback to Canada and the United States provides the strategic depth necessary for Pacific defense.

The shaping of an interactive C5ISR honeycomb covering both strategic geometries in the region is an essential element in the formation of a 21st century Pacific strategy. Japan can play a key role in this effort as she modernizes her air and maritime forces and works to provide for as seamless an integration of those forces as possible in the years ahead.

Clearly, air power is a key enabler for such a policy.

As the White Paper sketches out the reason for selecting the F-35, the need for an advanced fighter and its role in shaping a C5ISR enterprise were emphasized.

Since the military capacities in regions surrounding Japan are modernizing, it is becoming increasingly important to improve the comprehensive air defense capability, with fighter aircraft acting in an integrated fashion with their support functions; more specifically, the development of frameworks for air defense, etc. that can deal with the following situations is becoming a pressing issue:

- The emergence of high-performance fighter aircraft with excellent stealth capability and situational awareness (SA) capabilities;

- Further increases in cruise missiles with excellent stealth capacity; and

- The development of network-centric-warfare, in which fighter aircraft, the Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS), aerial refueling tankers, and surface-to-air missiles (SAM), etc. form part of an integrated system.

In other words, the new fighter aircraft needs to be able to effectively deal with high-performance fighters, as well as being equipped with sufficient performance to deal with cruise missiles and the ability to carry out its operations effectively in network-centric-warfare that has those functions as constituent elements.

Moreover, with weapon systems becoming increasingly high-performance and expensive at present, all weapons are becoming increasingly multirole-focused (multifunctional), from the perspective of cost-effectiveness as well, and this trend is particularly pronounced in the field of fighter aircraft. Furthermore, in light of the fact that the security challenges and destabilizing factors surrounding Japan are becoming increasingly diverse, complex and multilayered, the new fighter aircraft are required to be multirole (multifunctional) aircraft equipped not only with air superiority combat ability, but also with the ability to carry out air interdiction3 (air-to-ground attack capability), at least.

Obviously other elements of shaping a more agile and effective defense approach are significant as well, for example, in the integration of space capabilities into an overall defense and security enterprise.

The Ministry of Defense will promote new development and use of space for the national security in coordination with related ministries, based on the Basic Plan for Space Policy, the 2010 NDPG, and the Basic Guidelines. In FY2012, it will address projects such as 1) research for enhancement of C4ISR utilizing space, 2) enhancement, maintenance, and operation of X-band SATCOM functions, and 3) participation in the USAF Space Fundamentals Course.

Of these, with regard to the enhancement of X-band SATCOM, in light of the fact that two of the communications satellites (Superbird-B2 and Superbird-D) used by the Ministry of Defense and Self-Defense Forces for command and control of tactical forces are due to reach the end of their service lives in FY2015, these satellite communications networks will be reorganized.

This reorganization will facilitate high-speed, large-capacity communications that are more resistant to interference, in order to accommodate the recent growth in communications requirements, as well as integrating communications systems, thereby contributing to the construction of a dynamic defense force.

Japanese policy is shaped as well by the experiences of responding to events.

The “Great East Japan Earthquake” and its challenges provided a significant opportunity to shape new approaches moving forward. This event re-enforced the clear need to reform crisis management response mechanisms in Japan.

According to the White Paper:

These activities marked the largest mobilization of personnel and equipment in history, and close cooperation was carried out between the military of the United States and other countries, the various headquarters of the Government, related ministries and agencies, local governments, and others. This also marked the first time that ready reserves and reserves were summoned based on the Self-Defense Forces Law other than in exercises. Thus, the SDF employed full-scale efforts in order to ensure the safety of disaster victims and stability for the lives of those in the region.

And responding to real world events such as the earthquake can have other concrete events as well. For example, in a conversation with senior Japanese officials involved in dealing with the Tsunami and reactor meltdown crisis, the officials discussed the significant challenge of recovery in the midst of a crisis.

“We were prepared for single instances of crisis, flood relieve, Tsunami recovery, nuclear reactor problems; we were not prepared for simultaneous incidents which created a collapse. In shaping a response and recovery strategy, a key problem was an attempt to apply single incident plans to the crisis. We focused initially on defining the crisis as a nuclear meltdown and tried to approach the crisis this way, but that only worsened the situation as the entire population in the core area hit by floods, etc. were panicked by the meltdown, but unable to move and to focus on their ability to have proper help to provide for tactical and strategic mobility.”

According to these officials, it was crucial to be able to apply tools, which would buy the Japanese leadership with time to peel back the elements of the onion in order to start the recovery process. “We did not have the proper tools in place to allow us to move people and to restore confidence.”

The U.S. offered various types of aide in the situation, but the initial platform whereby aide came was in the form of carriers and amphibs to provide supplies for relief.

“At first we focused on direct relief, but soon came to realize that the sea bases provided significant alternative hubs to manage the movement of persons and to provide a sense of mobility and support to a population which hitherto felt trapped. In other words, the sea bases became instruments not simply of relief, but facilitated recovery and reconstruction. They became much more than supply depots to help the endangered population; they became part of the infrastructure for recovery and reconstruction. Obviously, the aircraft aboard these ships, notably the helicopters, became part of the mobility team able to not supply but move people strained in the situation. The sea base became a visible reality to the Japanese people of how to overcome the limits of an island nation facing such catastrophe.”

In short, Japan is in the throes of change, and how their approaches intersect and impact on those of the United States and the allies will go a long way towards shaping the shape and effectiveness of a 21st century Pacific strategy.

Feature Image: Bigstock