10/22/2011 – Second Line of Defense sat down with recently retired Lt. General Desclaux. Desclaux’s last command was as French Commander of Air Defense and Air Operations for the French Air Force. The General has a distinguished and comprehensive background in air operations, with significant NATO experience as well.

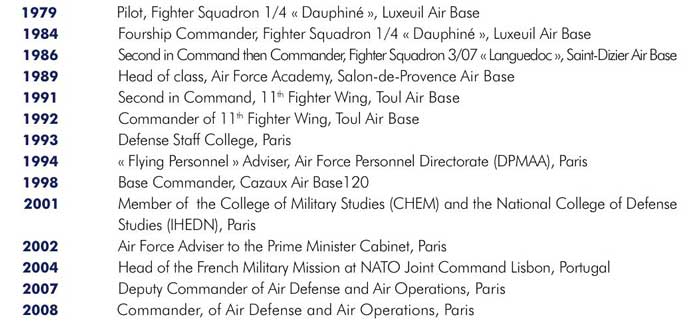

An overview of his background and experience can be seen below.

SLD: Could you describe what was unique about this operation for the French Air Force? And I believe this is first combat other than Afghanistan in which the French Air Force has been involved in a major NATO operation with France a fully integrated military member.

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: Most of the French air forces were involved in the operation, whether land-based or sea-based, including use of attack helos. The French General Staff was extensively involved in shaping the tactics and strategy of the NATO operation as well. In the Gulf War and in Bosnia, we were mostly following what the Americans were planning; this time, because of less intensive US commitment, it was clearly different.

We involved all Air Force capabilities, with the exception of some GBAD (Ground Based Air Defense) capabilities.

But what was indeed unique, was the initial entry we have performed on the first day of the operation, on Saturday the 19th of March. The game plan was to be ready to follow the political tempo and to react to the very fast evolving situation on the ground. Thanks to our very flexible and reactive C2 organization, we were able to achieve Air superiority over the Benghazi area during the Paris heads of state conference and finally, around 1745 local time, to stop the Gaddafi tanks column, 10 km south of Benghazi.

SLD: With regard to command and control, prior to the operation, it was not clear who or how this would be done. What were your expectations?

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: At the beginning of the discussions, I thought we might lead the operation. We worked closely with the British to stand up very good C2 for the operation and there was the possibility that this joint capability might have operated from Lyon, where the French AF main C2 capability is located.

SLD: There is a history here of French and British cooperation in C2.

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: Yes. For example, we organized a combined C2, JFACC (Joint Force Air Component Commander) and associated capabilities in 2005 with the British; 60 percent French, 40 percent British for the first rotation in NATO Response Force 5. And for the following rotation, the sixth, NRF-6, it was the reverse; 60 percent British, 40 percent French.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joint_Force_Air_Component_Commander

Then we have a long experience of sharing and working together, mixing our capabilities, especially our C2 capabilities.

President Sarkozy and the British prime minister were in favor of a French-UK C2 because the appetite of the other nations was not obvious at the beginning of March. At this time, we were preparing to assume the command of the NATO Response Force 17, and my JFACC was ready to conduct the certification exercise Noble Ardent 11. My JFACC was fully equipped with 300 positions in Lyon.

SLD: A particularly interesting aspect of the operation was the use of the naval assets in coordination with the land based air assets.

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: The Air Force assets, the Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier, the amphibious ships and the frigates were involved in combined strike operations. On one hand, the frigates provided gunfire support with their 100-mm guns for the operation of the helos off of the amphibious ships. On the other hand, the air assets whether land based or from the carrier supported the various helos, the Tigers, the Gazelles and the Caracals, providing C2, recce, air superiority (wild weasel) or close air support if needed.

SLD: Another important aspect of the operational experience was that the sea base was being used for your recce assets to dump information for processing as well.

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: They were being used for both relay and engagement.

(For a look at Rafael operations aboard the Charless De Gaulle see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0lhpe8TCLX4.)

The initial ops were from France. One can easily see why multiple bases closer to the operation were critical to mission success. (Credit: http://bit.ly/qto2MY)

The initial ops were from France. One can easily see why multiple bases closer to the operation were critical to mission success. (Credit: http://bit.ly/qto2MY)

SLD: Another aspect of the operation was that you used multiple bases from which to operate your aircraft.

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: The first two days we operated from Saint-Dizier, Dijon, Nancy and Istres and Avord. Because since the first day, our objective was to base nearly all the assets in Solenzara (Corsica), we needed to build a robust logistical support during these first two days and to bring many capabilities to Solenzara. Basing in Solenzara was very relevant for this operation; we have a big ammunition depot; the runway is fully equipped and ready to host at least three squadrons of 15-20 aircraft. This is a base much closer to the Libyan coast line.

Souda Bay was also important operating off of Crete. We operated here with the Qatari Mirage 2000-5s. And it has been a nice progression because at the beginning, they were performing only air-to-air, and at the end, we were able to help them doing some air-to-ground missions.

Later on we were able to operate our Rafale out of Sigonella as well.

SLD: Most of the bombing runs were done from Souda after the initial operations?

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: Yes. It was easier to put all the bombing assets in a single place. Supporting was easier because after three months of operations, you are looking for cost-effective solutions because you don’t know how long this operation will last and costs are always a major issue.

SLD: Did you use UAVs in the operation as well?

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: We did. We operated the Harfang (“Eagle”) UAVs from Sigonella. Harfang is a UAV provided by EADS. It is an Israeli airframe with EADS electronics.

SLD: What were the advantages to operate the Rafale from the Charles de Gaulle?

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: Basically, in the AOR, whether the Rafale was air or navy, it was conducting the same type of mission; 70 percent dynamic targeting, and 30 percent deliberate targeting. Obviously the advantage of being on an aircraft carrier is you’re closer from the theater of operation. The disadvantage when you take off from a French carrier is that your Rafale brings less ammunition than when taking off from a runway.

For example, with the Rafale from land, you can take off with two cruise missiles, as from the carrier it’s only one. The air force Rafale can take off from the land with six 250 kilos bombs – from the carrier, it only was four. You’re closer but you bring less ammunitions and you need gas anyway because in the dynamic targeting operation loiter time is important to mission success.

SLD: The amphibious ships were an important part of the air operation.

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: They were. On the Mistral, it was very interesting because when we are conducting the night assault with the helicopters, a few hours before the helicopter runs, we were sending Rafale, downloading the imagery on the Mistral or on the Charles De Gaulle, and then the intel officers were preparing the targets for the helicopters and they were taking off with very fresh information on their targets.

SLD: C2 was crucial to the dynamic targeting phase.

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: Central. To be effective in such an operation, when you have a cap of aircraft operating over the targets, you need a good C2, able to analyze the Intel material very quickly and task the aircraft in-flight before the target disappeared. And for that, you need very good C2 skilled and experienced people. You need also good leaders in your combat floor, well trained to quick decision-making process and very motivated. That’s key. C2 is major in such operation.

Rafale loaded with AASM weapons (Credit: http://rafalenews.blogspot.com/2011/03/first-pictures-of-rafale-which-were.html)

Rafale loaded with AASM weapons (Credit: http://rafalenews.blogspot.com/2011/03/first-pictures-of-rafale-which-were.html)

SLD: Could you describe the operational plan a bit further?

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: On the first day the tactical plan basically was to minimize the number of aircraft on land and then to use only the Mirage 2000 at a reasonable height to avoid surface to air missiles. In the Cyrenaica area, we knew that only a very limited number of SA-24, the latest version of the SA-7, and a few SA-8 were present.

The Mirage 2000 with their targeting pods were not only dropping bombs but also extracting the coordinates for the Rafale. Then the Rafale used their magic weapon, the AASM. They dropped their weapon at 50 kilometers from the target. It’s a boosted weapon inertial/GPS-guided and the Rafale can deliver 6 of them in a single run on 6 different DMPIs.

We have used some in Afghanistan, of course, but not at this distance. In Afghanistan, we drop this air bomb without using the booster because you are in the vicinity of the target. Libya was the first employment using fully the range of the booster, 50 kilometers or 60 kilometers when you drop them at reasonable height

SLD: Obviously, rules of engagement were important with the need to avoid civilian casualties and in this situation avoiding casualties was very difficult.

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: Absolutely, the guidance was to avoid at the maximum extent civilian casualties. There are two ways to do that. Either you have ammunition able to destroy targets with a very low CDE, with minimum collateral damage estimate possible or you have to really understand what is going on the ground, where are the civilians, where are the bad guys, how they are operating and to be very selective in your targets.

And that’s the problem. That means whether you have nice ammunitions to do it or you have to have a very good awareness. You have to rely on full-motion video, for example, to really understand the pattern of life around your target, to be able to assess that you will not kill civilians.

Just to give you an example, we had the idea, which is not a brilliant idea, but to employ inert bombs to destroy the vehicles in urban areas. We were using Paveway III guidance kits associated with inert bombs and we had some success.

But the only way to be effective is to hit directly the target. If you drop your bomb at one meter, you get no effect. Then we dropped a few of them but we had a limited success, less than 50 percent of direct hits. We did that for two weeks and then we decided to stop because the GBU-22 kit is a bit expensive and to have a success rate of 50 percent is not very cost-effective.

SLD: You used UAVs in the operation some provided by the US. What was your experience here?

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: We had too limited a capability. We could cover only two operational areas and for a limited period of time. The war was developing in four different areas, and the minimum for such an operation should have been for 24/7

In fact at the beginning we had the duty to act as firefighters and to stabilize the situation what we have done well. But the “what’s next” phase was not well anticipated. We had no real plan, no real good end state; we should have had a more forward-looking approach when moving beyond the initial Benghazi and Misratha operations.

After this first containment phase we needed a plan that did not simply react to Gaddafi tactics but able to regain initiative and to put a strong pressure on him and his supporters. We needed a better understanding of what are the center of gravity of Gaddafi, its critical capabilities and resources, to better target them and force him to stop and resign. I think we have spent too much time reacting to Gaddafi’s strategy.

Other limiting factors slowing down the success of the coalition were the constraints of the mandate and the necessity to maintain the cohesion of the Alliance where different views on this crisis had to be managed.

To cut Gaddafi forces’ supply and target the south part of Libya where he was relaxing and was gaining support from outsiders, were critical to success. You cannot make a war with your opponent having a safe haven where he can bring more forces, bring more capabilities.

SLD: Going forward what would you recommend for the future?

Lt. Gen. Desclaux: To be able to face an agile and adaptive enemy, first you definitively need a robust persistent ISR capability. Second, we need to give more authority to the pilots, to the cockpit. No matter how good your centralized C2 might be, it should not be always in full control of the weapon delivery. In the Libyan operation decision making-process was in many cases slowed down excessively. Doing that, C2 leaders will be better focused on the strategic or broader tactical coordination issues. Micromanagement of what the pilots can do by themselves will not create good outcomes. And finally this operation showed us clearly once again that “planning is everything”!