2017-05-01 By Robbin Laird

Two years ago during a visit to Australia, I had a chance to interview the head of Thales Australia, Chris Jenkins.

In that interview, we focused on the business model followed by Thales in Australia, namely to transfer technology, grow indigenously and export from Australia.

The Government’s commitment to building a 21st century combat force continues, and new programs like the submarine program have been launched as part of that modernization process.

During my April 2017 visit to Australia, I had a chance to talk again with Chris Jenkins, but this time focused on the broader issues of the relationship between industry and government in the Australian defense sector.

Jenkins is not only CEO of Thales Australia but is also National President of the Australian Industry Group, Chairman of the AIG Defence Council, and an Advisory Board member of the Centre for Defence Industry Capability.

He has a longstanding involvement in large-scale projects in critical industry sectors, and was previously Chairman of the International Centre for Complex Project Management, as well as a member of the Defence Portfolio Ministerial Advisory Council and the DSTO Advisory Board.

Question: The Australian government has set in motion a significant modernization programs.

What is the role and impact on industry?

Chris Jenkins: There are several aspects to that subject.

Australia is spending more on defense. At the same time as doing so, there have been clear changes within defense as an organization to shape new ways to implement that policy, following the First Principles Review and its recommendations.

There’s also been very clear policy around enhancing the impact of defense modernization on Australian industrial skill sets.

There has been keen interest to enhance the level of engineering and technology and program management skills and to grow those skills over the long term, both within the Defence industry sector but also more broadly in Australian industry.

I’ve been really impressed that within a very short period of time there’s been buy-in from the defense service chiefs, and changes within the defense acquisition and sustainment organization to start to implement these policies and make them real.

Overall the most important impact, in my view, is the inclusion of industry as a Fundamental Input to Capability (FIC) for Defence.

This drives a new, more integrated relationship with mutual responsibilities between Defence and industry.

This really gets to the heart of how industry can be engaged as a FIC.

Finding more effective paths to deliver integrated capabilities within and across Defence platforms and systems is something that can only be done efficiently by close partnering between Defence and industry.

Chris Jenkins, CEO Thales Australia and National President of the Australian Industry Group, Chairman of the AIG Defence Council, and an Advisory Board member of the Centre for Defence Industry Capability.

Chris Jenkins, CEO Thales Australia and National President of the Australian Industry Group, Chairman of the AIG Defence Council, and an Advisory Board member of the Centre for Defence Industry Capability.

Question: I spent time with the head of Air Force this morning, Air Marshal Davies, and he is keen on shaping an integrated force.

It is not just about platforms, but finding ways to deliver integrated capabilities.

What is the challenge and impact on industry of such an approach?

Chris Jenkins: There are very clear actions being taken to support that by the service chiefs and by the people in the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.

You’re also seeing industry gaining confidence in the approach as the new paradigm. Industry is also starting to work more collaboratively together, forming the team sets that can deliver and evolve combined platform and system capability.

Companies are starting to work together to share workload because of the complementarity of the skill sets that one company might have compared to another.

Industry is responding to the opportunity to engage in a collaborative set of partnerships between defense and industry and this is showing some good results in terms of greater delivery and sustainment capability.

Prior to these government initiatives, Australia has been one of the lower end performers on collaborative development.

Reshaping this relationship is crucial to get the kind of success Australia wants through more efficient, more agile integrated capability delivery.

Question: Clearly, this means that even when platforms are bought abroad, there needs to be a working relationship where that platform evolves over time within an ADF context, not simply replicating whatever has been done to modernize the platform in the originator’s home market.

How will Australia do that?

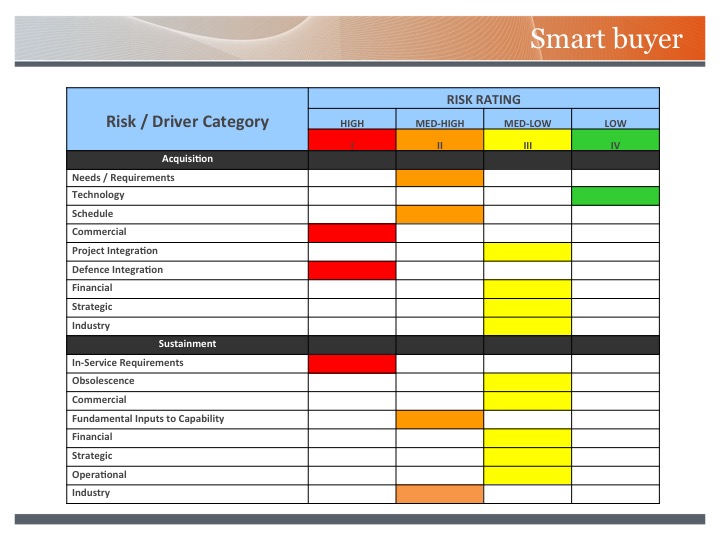

Chris Jenkins: There’s a smart buyer approach in the market now, which is looking for the elements that will go onto the key platforms that are specifically focused on the Australian defense requirement.

Rather than buying a complete platform and system from overseas off the shelf, I think the realization is Australia does have some unique operational requirements, and so building into the procurement process a way of evaluating how best to bring those teams together that can deliver and sustain those requirements through the life of the vehicle, or the ship or whatever it might be, is being done more efficiently and effectively.

This slide was presented as part of Rear Admiral Tony Dalton, Head Joint Systems Division, Australian Ministry of Defence’s brief to the Williams Foundation Seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017.

This slide was presented as part of Rear Admiral Tony Dalton, Head Joint Systems Division, Australian Ministry of Defence’s brief to the Williams Foundation Seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017.

The customer is helping shape the market or the way the market responds to the requirements more effectively. I think that is a fundamental change.

How well projects deliver as a consequence of that overall change, time will tell, but I think all signs are actually quite positive.

The first principles review made strong recommendations, and it looks like that the actions that need to underpin those recommendations are being taken.

Question: How does this evolving approach affect Thales Australia?

Chris Jenkins: It’d be difficult to observe and/or be part of the wider changes that are happening in defense industry and not be practicing them yourself in your own company.

The simple fact is that Thales in Australia has been a very strong supporter of the partnership approach with Defense but also as an industry teaming advocate.

We’ve been taking very proactive steps to put more work outside the company into our SME supply chain, and develop strategic and important relationships long-term with our SME suppliers, developing their capabilities, working with their design teams so that we’re effectively multiplying the engineering capability my company has access to by virtue of the engineering capabilities in our supply chain.

A good example can be seen in the case of the development of the Hawkei protected combat vehicle.

The vehicle is an incredible breakthrough in terms of capability for army, and I believe is globally leading in levels of protection.

We’ve been able to achieve that by having a very strong team of SMEs support us in the design phase, so that all the innovation, fresh ideas that come from those SMEs, is built into our Hawkei design.

That now creates a very positive outcome not only for the company, a great outcome for defense, but it’s a great outcome for the SME backbone of the defense industry based in Australia.

Question: Key platforms are being bought which are software upgradeable.

This means a very different approach to upgrading and modernizing platforms, and if you want to shape an integrated approach you clearly need to find ways to shape cross cutting software integration.

How do you do this?

Chris Jenkins: The Defense Department for a long time have been saying open architecture’s what they want to see in platform systems.

The goal is to be able to insert, with relative ease, new software developments, new applications, new functionalities, to enable agility, the ability to adapt the capability in our systems more rapidly.

We learned a lot about that in Afghanistan with some of the land-based platforms we had.

We have also learned about the capability advantage of having open architecture in things like Australia’s submarines and surface ships as well.

Today, what we’re seeing is that open architecture capability is really being valued in the acquisition process, and we’re seeing the service chiefs and the forces being much more effective in requesting and getting open architecture implementations for the systems into ships and vehicles and so on.

It’s putting pressure into some suppliers to review their previous business model of delivering hardware and software “locked in” to a single source of capability upgrade. It could be communications systems or battle management systems or whatever.

The new model is going to be open architecture.

This brings much greater flexibility and speed to adapt to changing operational needs.

We found that in the Bushmaster vehicles going to Afghanistan, with the upgrades to systems progressively through that whole conflict.

The number of capabilities that were trying to be inserted in the vehicle required hardware changes, more and more hardware being built up inside the vehicle, more power demand, more weight and a great difficulty to ensure the safety of the people inside the vehicle.

Just the practical aspects of getting the equipment in there are a problem, but it means you have lots of equipment that can be dislodged during a blast.

It becomes very difficult for the occupants, say for example, of the Bushmaster.

Some of the work done on the Hawkei learning from the Bushmaster experience was to create only a single integrated computing system with open architecture that then allows all the suppliers that Defense wants to work with to drop in their communications systems, their remote weapons system, their surveillance system, their battle management system.

The simple matter is exactly as you say.

That’s where the market is going.

That’s what defense forces want, and of course from an agility standpoint that’s what they need to have, so industry has to adapt how it works to make sure we make this happen quickly.

There are some very good examples of that now happening.

I think it’s a great change.

It’s a real change clearly delivering the agility our forces need.

Question: My final question is about the submarine program.

A new submarine is being built by DCNS of which Thales is a major shareholder, and by Lockheed Martin with regard to the combat system.

What role might Thales Australia play in this program?

Chris Jenkins: Lockheed Martin is the combat systems integrator on the new submarine where Australia is looking for a combination of interoperability with the United States and integrateability with the ADF.

Artist’s rendering of short fin barracuda. Credit; DCNS

Artist’s rendering of short fin barracuda. Credit; DCNS

What we have experienced with the Collins class submarines and their upgrades is the capability to integrate our sonars with Lockheed and Raytheon software.

We’ve been doing it for over 30 years with the Collins-class submarine program, with the sonar systems we’ve been producing and putting onboard.

Throughout this time Australia has developed in our sonar team working with Defence, Navy and very importantly the Defence Science and Technology Group, the essential knowledge and skill sets to design and develop some of the most advanced sonar sensor and systems capability in the world.

Obviously, we look forward to continue to do that on the new submarine.

In sensitive areas like submarine technology, we are well positioned I think, for us to work well with both Lockheed Martin as a combat system integrator on the future submarine and with DCNS obviously as the platform provider and the vehicle upon which the sonars must perform optimally.

That’s for me a good combination of companies for a very complex project, and a program of such great importance to Australia.

I think you need companies with a high level of maturity in this very specific area of sovereign capability to mitigate the through the life of such a program.