2017-04-27 By Robbin Laird

On April 11, 2017, the Williams Foundation held its latest seminar on shaping a way ahead in the shaping of a 21st century combat force.

This seminar followed a series of seminars exploring the coming of a fifth generation force and the way ahead for reshaping the ADF into a more lethal and effective joint force.

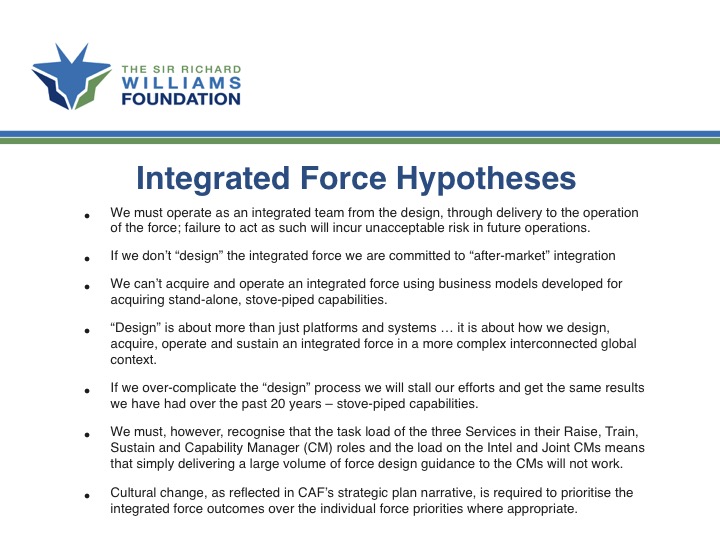

The Terms of Reference for the Seminar were as follows:

Integrated Force Hypotheses Discussed During Williams Foundation Seminar, April 11, 2017.

Integrated Force Hypotheses Discussed During Williams Foundation Seminar, April 11, 2017.

And as part of the seminar effort, a case study of the nature of the challenge to be met with regard to integrated force design, namely, a careful look at Integrated Air and Missile Defense.

In preparation for the Seminar, the Williams Foundation has run a six month IAMD Study, exploring the challenges of the IAMD program and the concept of integrated force design, as one example of the forty programs that the Department of Defence has embarked upon.

The IAMD Study Report will be launched at the seminar.

The Context

The program featured a number of the key officials involved in building the integrated force within the Department of Defence along with industrial stakeholders as well in the redirection of DoD design efforts.

The focus of the day was to have an honest set of presentations and debates about what was realistic, and what was not; what key drivers of change required more integration within the force as well as the importance of domain competence as the force is reconfigured for more joint effect.

It was an unusual seminar in that were more questions than answers; but what was clear was that the notion of reshaping the force for greater joint effect was a vector of change and not simply implementing a set of abstract principles.

But what did emerge was a fairly clear sense of the core realities and requirements needed to move to this next step – namely designing the force for greater joint effect.

The ADF is in the throes of significant modernization as new platforms are acquired and new approaches adopted.

And the ADF is working to provide the extended defense of Australian territory, which by its very nature needs to see significant integration among, ground, air, maritime, space and cyber domains.

The legacy approach has been to acquire platforms and then to cobble together linkages among the platforms to create a “joint force.”

But this is simply after market linkages rather than thinking through how to integrate more effectively from the ground up as new platforms are acquired or legacy systems modernized.

Air Marshal (Retired) Brown, Chairman of the Williams Foundation, April 11, 2017.

Air Marshal (Retired) Brown, Chairman of the Williams Foundation, April 11, 2017.

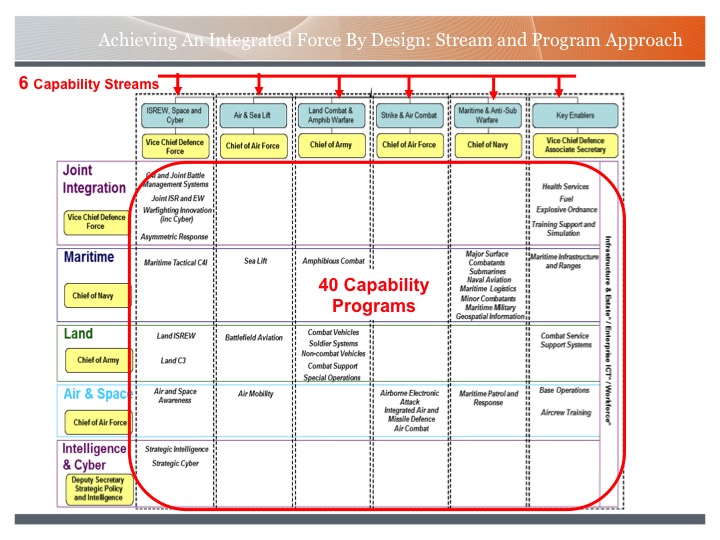

The key shift being envisaged is to move from the project approach to a program and capability stream approach.

The project approach is centered on platforms and linear acquisition within a fixed budget as the main trajectory.

A program approach considers several projects in their interconnection to get the kind of effect one would want to generate synergy.

And the capability stream approach introduced in the first principles review is seen as a key element of how to more effectively bundle individual efforts into a more synergistic whole.

In the first principles review, several streams or functions were identified to which platforms, and programs can be seen to contribute.

But the goal is to get more strategic visibility with regard to new platform acquisition or legacy modernization in terms of trade offs, which provide best value for money or best capability from an asset.

The First Principles Review of Defence outlining ways to craft a more effective One Defence approach was released by the Minister of Defense April 2015.

The key recommendations are laid out in the report but are summarized in the report as follows:

This review of Defence from rst principles has shown that a holistic, fully integrated One Defence system is essential if Defence is to deliver on its mission in the most effective and efficient way.

In order to create One Defence and give effect to our rst principles, we recommend Defence:

- Establish a strong, strategic centre to strengthen accountability and top level decision-making

- Establish a single end-to-end capability development function within the Department to maximise the ef cient, effective and professional delivery of military capability

- Fully implement an enterprise approach to the delivery of corporate and military enabling services to maximise their effectiveness and ef ciency

- Ensure committed people with the right skills are in appropriate jobs to create the One Defence workforce

- Manage staff resources to deliver optimal use of funds and maximise ef ciencies

- Commence implementation immediately with the changes required to deliver One Defence in place within two years

What was in evidence at the seminar was the initial results of the review in terms of shaping within DoD a more integrated approach to the evolution of the 21st century combat force.

It is obviously a work in progress, but you don’t know what you don’t know.

If you do not set of the objective of trying to optimize combat capability and consider that shaping the joint effect as a key means to doing so, then the challenge is clear: how to you get a strategic handle on where your force is moving to and how do you ensure that it is as effective, lethal and sustainable as possible?

In effect, what the Aussies are addressing is what Secretary Wynne highlights as the Macro Management challenges facing a Department trying to build a 21st century combat force.

“You can not build a force delivering fifth generation warfare capabilities with a stove piped management system.

“This is our challenge.”

The Need for a Strategic Approach

Notably, each of the Service Chiefs has put in place on the service level a very clear programmatic focus on developments in their domains with a growing regard to the joint effects.

And these Service Chief commitments have been in evidence in earlier Williams Foundation Seminars as well.

Put in other terms, the Service Chiefs are looking at the evolution of their capabilities from the perspective of how could they more effectively leverage other services and how might they more effectively support other services, dependent on the mission or tasks to be achieved.

Starting from that foundation, the next logical step is to try to gain a strategic handle on how the acquisition and modernization of assets can be more effectively conducted with regard to their synergy with assets within the joint force.

VADM Ray Griggs, Vice Chief of Defence Force, speaking at the Williams Foundation Seminar on Force Integration Design, April 11, 2017.

VADM Ray Griggs, Vice Chief of Defence Force, speaking at the Williams Foundation Seminar on Force Integration Design, April 11, 2017.

And this effort is very synergistic in term with the evolution of the evolving warfighting operational approaches and the concepts of operations, which are being developed to reshape the framing, and execution of core tasks and missions.

There are a number of key factors or reasons why getting a better strategic grip on the evolution of the force from a joint perspective is essential.

First, given the shift in focus to high intensity operations the need to maximize one’s combat effect compared to the adversary is essential.

A connected force can provide an advantage but only if it is synergistic and survivable; otherwise it is vulnerable and can generate fratricide rather than destruction of the adversary’s forces.

Second, the core enablers of combat power, such as C2 and ISR, are being dispersed throughout the services.

Creating a tower of Babylon is not the outcome you want to have.

Third, a number of the new platforms being acquired are software upgradeable.

It is desirable to be able to be able to manage tradeoffs among these platforms in terms of investments to get the best impact on the joint force.

It is also the case that getting the kind of transient advantage one wants from the software enabling the combat force requires agility of the sort that will come with applications on top of middleware on top of an open architecture system.

Brigadier David Wainwright, Director General Land Warfare during a panel discussion at the Williams Foundation seminar on integrated force design, April 11, 2017.

Brigadier David Wainwright, Director General Land Warfare during a panel discussion at the Williams Foundation seminar on integrated force design, April 11, 2017.

Fourth, much of the force, which will be operating in 2030, is already here.

This means that there will be considerable adaptation of the platforms towards greater joint effect.

How to ensure that the legacy modernization programs provide effective joint effects, rather than simply stovepiped upgrades?

Fifth, the information and communication systems, which are the enablers for the joint force, are dynamic elements subject to market change and adversary disruptions.

How to best develop IT and Coms packages which can support cross-cutting modernization and evolving force integration?

Sixth, to get the kind of cross cutting modernization one needs with an evolving 21st century force, how can the acquisition system be altered in order to provide for open-ended change?

How to move from a platform linear project approach to a broader program approach which allows trade offs to be made with regard to platforms within a capability stream?

Seventh, the only way there will be the ongoing rapid transformation of the force will be shaping an effective industrial-military partnership whereby there is shared understanding and shared risk to achieve outcomes which are more targets than well defined platforms.

How can this be achieved?

There are just some of the core questions, many of which were discussed during the seminar.

But the core point is that raising questions, which drive you towards where the force needs to go, is the challenge; it is not about generating studies and briefing charts which provide visuals of what a connected force might look like.

It is about creating the institutional structure whereby trust among the services and between government and industry is high enough that risks can be managed, but creative destruction of legacy approaches is open ended as well.

It is about empowering a network of 21st century warriors and let the learning cycle being generated by this network drive acquisition, modernization and operational concepts.

It is about innovations within concepts of operations generated by the network to flow up into strategic change.

The danger to such an effort is the bureaucratic desire even necessity to constrain chaos and to constrain change.

The focus can become on processes to the detriment of outcomes; the focus can become on shaping lightening bolts in charts showing how connected assets should be rather than allowing tasks forces and joint force packages to creative find ways to generate combat synergy.

It is also the case that the general can defeat the particulars.

What is needed is the generation of real world case studies of generating joint effects from cross cutting modernizations and synergy, rather than mandating a set of principles, which would appear on the wall of various defense organizations.

Guidance needs to be empowerment of the network; not providing detail lists of outcomes desired by the bureaucratic center.

The first principles review called for the creation of a strategic center; the danger is that it can become a center for process generation, and not the fostering of the kind of innovation which is required for shaping the joint effects need to prevail in 21st century warfare.

The Perspective of VADM Ray Griggs

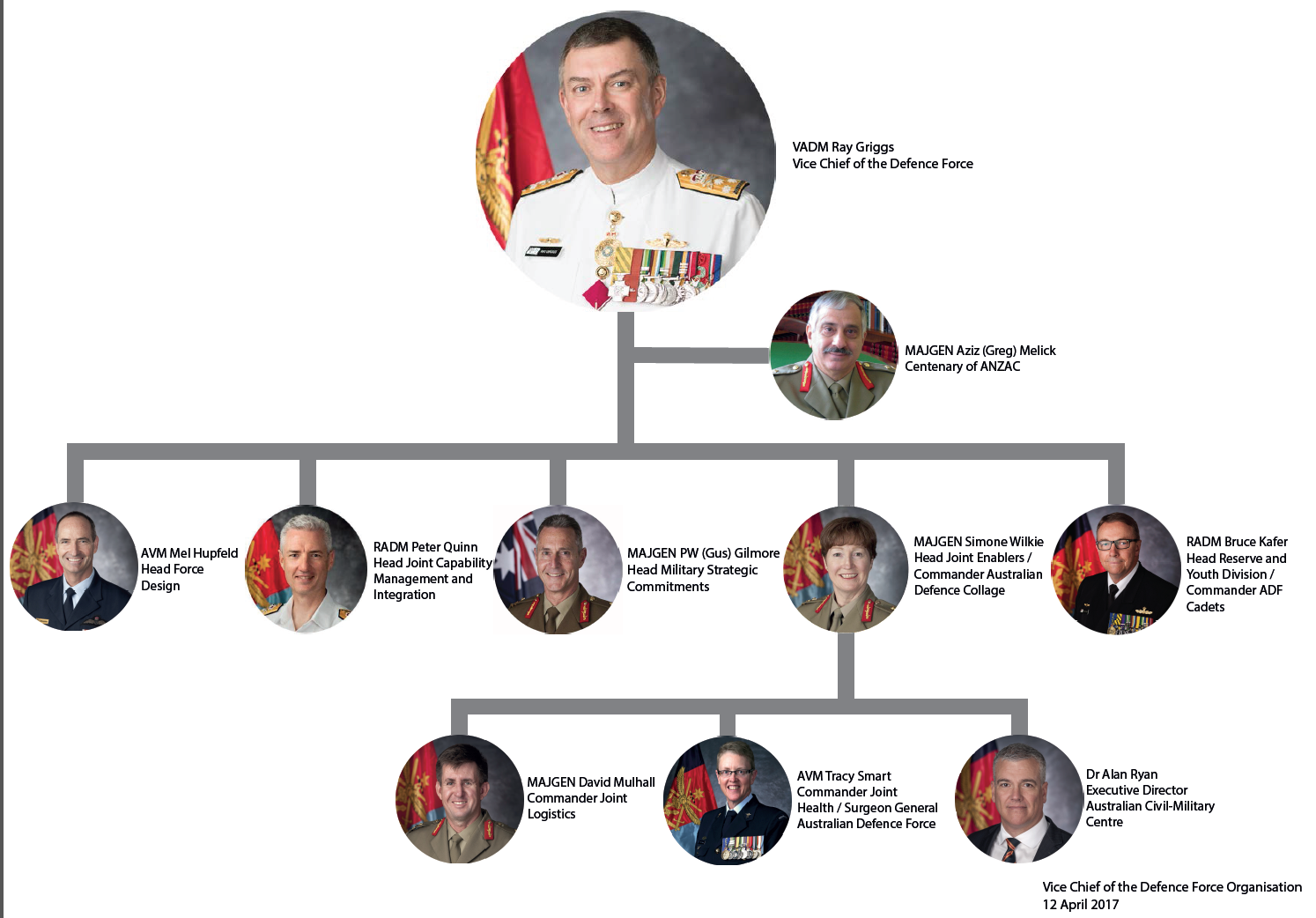

The first major presentation at the seminar was appropriately that by VADM Ray Griggs, Vice Chief of the Defence Force.

The VCDF Group was empowered by the defense reform process to spearhead the effort to build out the integrated force.

According to the Australian DoD webpage:

The VCDF Group enables Defence to meet its objectives through the provision of military strategic effects and commitments advice and planning, joint military professional education and training, logistics support, health support, ADF cadet and reserve policy, joint capability coordination, preparedness management, and joint and combined ADF doctrine.

Vision: The VCDF Group Vision is to be the Defence leader in the design of the Australian Defence Force structure and in the delivery of military enabling capabilities.

Mission: The VCDF Group Mission is to design and develop Defence Joint Capability and deliver military enablers in order to protect and advance Australia and its national interest.

http://www.defence.gov.au/vcdf/

The organizational chart below indicates his direct reports, and two of them are especially important to the focus of the seminar, namely the Force Design office headed by AVM Mel Hupfeld and the Joint Capability and Management and Integration Office headed by RADM Peter Quinn.

In his presentation to the seminar, VADM Griggs underscored that “we are seeing real changes in culture and behavior across defense.”

In part this is due to the fact that the warfighting domains are blending and becoming highly interactive with one another.

He argued that as we returned to a more congested and contested environment the five war fighting domains are becoming increasingly blurred.

Effective integration then is critical to gain superiority in 21st century warfighting.

He argued for an integrated strategic direction but flexibility in shaping operating concepts. “We need central orchestration of the effort rather than a top down dictat.”

He highlighted the need to shape a continuous capability review cycle within which to manage ongoing modernization, new acquisitions and effective management of trade offs in budget terms.

He chairs the investment committee where the principals met to make strategic decisions on investments. Obviously, control of the purse strings is crucial to make suggestions turn into recommendations with clout for force structure development.

And finally he saw the capability streams as key elements to reshaping the strategic approach to force structure development – as modernization choices are made.

The Perspective of the Force Design Division

And indeed, in the next presentation by Brigadier Jason Blain, Director General Force Options and Plans from the Force Design Division, the importance of shifting to a capability stream and program approach was seen as fundamental to the shift to enable enhanced joint capabilities.

Capability stream approach applied to force integration by design. Slide presented by BG Blain in his presentation to the Williams Seminar, April 11, 2017.

Capability stream approach applied to force integration by design. Slide presented by BG Blain in his presentation to the Williams Seminar, April 11, 2017.

BG Blain highlighted throughout his presentation a number of key principles or guidelines to the thinking within the Force Design Division.

Integration is a force multiplier.

BG Blain during a panel session held at the Williams Foundation Seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017.

BG Blain during a panel session held at the Williams Foundation Seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017.

If we don’t “design” the integrated force we are committed to “after-market” integration.

To enhance the ability to do integrated force design, the Division has developed a force design cycle whereby they evaluate opportunities to augment integrative efforts.

If we are not an integrated team from the design to the operation of the force, we will incur unacceptable risk in operations.

To get where Force Design Division wants to go with regard to integrated force design remains they need to engage in dialogue across the industrial and innovation ecosystem.

Design is about more than just platforms and systems…it is about how we design, acquire, operate and sustain an integrated force in a more complex interconnected context.

And to achieve such a design approach a number of key attributes need to be incorporated into the evolving approach:

- Force Design analysis of gaps and opportunities must consider the complete program design, including new integration challenges

- The Stream view will drive deeper understanding of how critical these challenges are to the warfighter in achieving joint effect sand reinforce the joint understanding of our gaps and opportunities.

- Force options must be developed with integration and interoperability as part of the up front design.

The Perspectives of the Services on Forging an Integrated Force

The next group of military presentations represented the services and provided a realistic sense of what the services wanted out of the joint design process.

They provided a sense of the constraints within which joint force design could occur, and the outcomes desired by the various services with regard to the joint effect.

But again, the Service Chiefs have already redesigned the way ahead for each of these services built solidly on a joint perspective.

What was in play in the presentations and discussions was not so much service stovepipes or focus on joint integration at the service level, but how best to leverage each service’s core competencies and how those competencies could support or be supported by the joint force, dependent on the tasks or missions.

The Air Force Perspective

The Air Force perspective was provided by former Plan Jericho co-team lead, Air Commodore Chipman.

In his remarks to the Williams Foundation seminar on force integration, he argued that integration, as a goal was laudable but not likely to happen as an abstract concept.

Air Commodore Robert Chipman, Williams Foundation Seminar on Force Integration, April 11, 2017

Air Commodore Robert Chipman, Williams Foundation Seminar on Force Integration, April 11, 2017

“I don’t believe that we share a common understanding about integration across the ADF or with our international partners.

“We place too much emphasis on whole of system design, rather than prioritizing integration efforts.”

He argued that integration would progress with clear focus on clear and realistic priorities.

And working organizationally to achieve core priorities would then open the pathway for accelerating real achievements with regard to decisive integration efforts.

Leveraging networks, leveraging sensors, and off boarding strike are key aspects of integrative behavior but sharing is not in and of itself integration.

In many cases, collaboration is sufficient as the means to achieve the joint effect, rather than a whole of system design.

“We need to integrate sufficiently to take advantage of networked capability.

“That is why network taxonomy is so important in clarifying priority efforts to achieve greater capability to leverage networks and deliver a joint effect.”

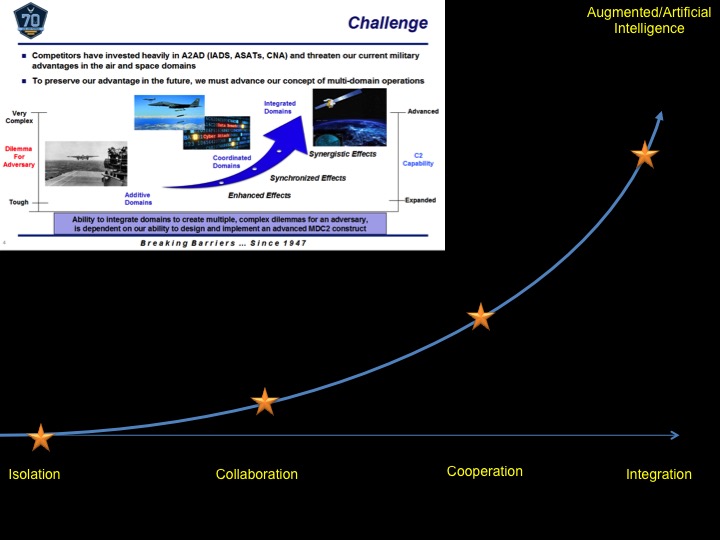

In the taxonomy, he highlighted that there are four levels of operational dynamics with regard to networks: isolation, collaboration, cooperation and integration.

Taxonomy used by Air Commodore Chipman to prioritize program efforts. Slide was part of his presentation to Williams Foundation Seminar April 11, 2017.

Taxonomy used by Air Commodore Chipman to prioritize program efforts. Slide was part of his presentation to Williams Foundation Seminar April 11, 2017.

In effect, arguing the best could be the enemy of the good, Air Commodore Chipman argued that in many cases pursuit of collaboration or cooperation will deliver the superior combat effect than to enforced integration, particularly if such efforts reduce the force to the lowest common denominator.

“And this effects prioritization.

“We want E-7 integrated with Air Warfare Destroyer and both able to cooperate with JSF.

“Which elements need to be tightly integrated versus generating cooperative effects for the ADF?”

He argued for a pragmatic, flexible, and priority driven approach.

“We need to generate thrusts forward in terms of greater combat effect. Integration is not a stationary target and after-market integration efforts will always be required to enhance collaborative and cooperative capabilities within the force.

‘We need to have the flexibility to deliver aftermarket-integrated effects as a core activity as well as designing in integration from the outset where feasible.

“It depends on the priority for enhanced combat force performance.”

The Army Approach

Brigadier General David Wainwright, Director General of Land Warfare in the Australian Army, provided the Army approach.

In his presentation and discussions at the Seminar, he highlighted the thinking of head of Army with regard to Army modernization with a core vector on the integrated force.

He quoted Lt General Angus Campbell’s comments made last year to the Lowry Institute for International Policy.

“The Army and more broadly the ADF needs to be able to influence and shape effects from and across multiple domains, as other protagonists will seek to do against us.

“This is why mastering ‘joint operations’ is even more important and much harder than ever before.

“We need to generate, coordinate and anticipate multiple cross-domain actions and reactions.

“No one service or domain can or will have a monopoly on success.”

And then added the comment by Lt General Campbell made in the same presentation last year with regard to the nature of real world challenges and combat outcomes as a driving test of combat success.

“Notwithstanding the proliferation of technology and the associated emergence of new domains, war without submission requires decision on land, where people live.

“The need for Orwellian ‘rough men’ (and women) is not going away anytime soon.

“War as a contest of wills, settled by close combat, is the enduring responsibility of the Army.

“However, the context in which that contest takes place has and continues to change.”

The focus of BG Wainwright’s presentation was on the outcome of evolution of the jointly enabled and jointly contributing ground maneuver force.

“The Land Force Must be ready to fight into, through and beyond Complex Terrain – Here I will steal the Marine Corps definition of complex terrain; where the additional layers of informational and human complexity further complicate traditional geo-physical challenges.”

“Future land forces will face unprecedented levels of complexity in cluttered, congested, hyper-connected and lethal future operating environments.

“Even the most benign mission may pose hidden challenges.

“This will require ready land forces capable of achieving tactical objectives in complex, possibly contaminated urban environments – in and amongst fragile populations; all while being challenged across multiple domains, simultaneously.”

“The Land Force Must have the ability to form robust, lethal, and networked combined arms teams; fully integrated into the wider joint force and capable of operating dispersed or distributed, then to aggregate rapidly to deliver precise and discriminate effects.

“Not simply another insatiable consumer of information, fires and enabling support, or a stand-alone ‘battlespace owner’… but a true joint player capable of delivering and integrating joint effects in partnership with, and as an important element of a larger inter-governmental, interagency and multinational team.”

“Land forces must be survivable. Even the most seemingly benign operational contingencies can deteriorate rapidly and even the smallest commitment can require hard fighting, against well-equipped, determined and adaptive enemies.

“As much as we might wish for a future where long range sensors and stand-off fires mitigate the joint force need for land forces ready and prepared for the demands of sustained close combat in complex terrain – this represents wishful thinking, not sound force design.”

“Moreover, the proliferation of next generation Air to Ground Missiles, explosive Unmanned systems, loiter munitions, advanced IED and mines, CRBN threats including everything from chemicals to thermobarics,

“And the consequences of efforts to disrupt our access to the Electro magnetic Spectrum and space borne enablers must be accounted for by a holistic approach to survivability and force protection.”

“To achieve this will require the Integrated Joint Force to evolve from the best-equipped Army in our history, to the best-equipped land force, of its size, in the world.”

The land force needs to be inherently joint given the evolving nature of warfighting domains.

“Future land forces must be capable of potent cross-domain effects – projecting landpower from the land into multiple domains, including the electromagnetic spectrum and the arena of human perception.

“This will undoubtedly create new challenges, demand new responses and require cultural change to see where land forces may best serve the interests of the joint interagency intergovernmental and multinational ‘team of teams’.”

The Navy Approach

CDRE Spedding, RANR, DG Navy Program Support and Infrastructure provided the Navy perspective.

His presentation like that of BG Wainwright focused on the kinds of outcomes which Navy needed to achieve both to leverage and to contribute to enhanced joint warfighting effects.

The Australian Navy has moved from a perspective of providing single naval assets to work alongside core allies, notably the US Navy, to providing task forces to meet government objectives.

The focus upon building and operating task forces inherently requires integration at the task force level; and leveraging the task force to support government objectives inherently requires broader level of ADF and government integration within combat and political objectives.

The shift to a continuous shipbuilding strategy provides a significant foundation for how navy will address its modernization needs within a joint strategic framework.

Naval platforms have both static and dynamic elements.

The static elements will be grounded in fundamental ship design and maritime operating demand.

The dynamic elements, combat systems and weapons, will be software driven and inherently open to integration with the joint force.

And the adoption of the Ship Zero concept provides an opportunity to provide a test bed for continuous development of the dynamic systems carried onboard maritime platforms.

In my interview with Chief of Navy last year, he discussed the Ship Zero concept as a foundational element in the way ahead for the Navy to provide for more rapid combat innovations.

Question: Wedgetail shows an interesting model, namely having the combat squadron next door to the Systems Program Office.

This facilitates a good working relationship and enhances software refresh as well.

You have something like this in mind for your ship building approach.

Could you discuss that approach?

Vice Admiral Barrett: “We do and are implementing it in our new Offshore Patrol Vessel program. And with our ‘ship zero’ concept we are looking to integrate the various elements of operations, upgrades, training and maintenance within a common centre and work flow to get greater readiness rates and to enhance an effective modernization process as well.

“We are reworking our relationship with industry because their effectiveness is a key part of the deterrence process. If I have six submarines alongside the wharf because I can’t get them away, they are no longer lethal and they are no longer a deterrent force.

“Again, as an example we have dramatically improved availability by building maintenance towers alongside the submarine—rather than the previous way that it was done, where people arrived into that one gangway under the submarine then dispersed to do their maintenance work—is an example of how we need to work.

Key Strategic Challenge: Building the Integrated Force While Fighting With the Force You Have

The final three military presentations focused on the challenges of shaping a more integrated force fighting with the force you have while you are incorporating new platforms, software, communications systems and other key assets within the ADF.

How do you fight with the force you have while you pursue development of a more integrated force?

RADM Tony Dalton, Head of the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, focused exactly on that question.

Rear Admiral Tony Dalton making his presentation at the Williams Foundation seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017.

Rear Admiral Tony Dalton making his presentation at the Williams Foundation seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017.

“How does the legacy force come into play and affect new platform decisions?

“Before we can think about a future integrated force we have to make decisions now about force upgrades and modernization.”

The shift, which needs to be made, is to ensure that upgrades and modernization of the legacy force are informed by options to shape a more effective force.

“We have to work with the projects that are already in play and several of these simply do not point the way forward for a more fully integrated approach.”

And if we are going to open the aperture with regard to more flexible development within the force, the challenge of how to manage cost is crucial.

“If we buy an off the shelf system our schedule as well as costs are on a solid timeline.

“When we Australianize a system cost will go up 12-15% and with it schedule slippage.

“And if we are talking developmental systems we are looking at a 25-30% cost increase and with it schedule slippage as well.”

He highlighted that in the smart buyer approach currently in place, the contribution of a particular project to overall force integration was a key consideration.

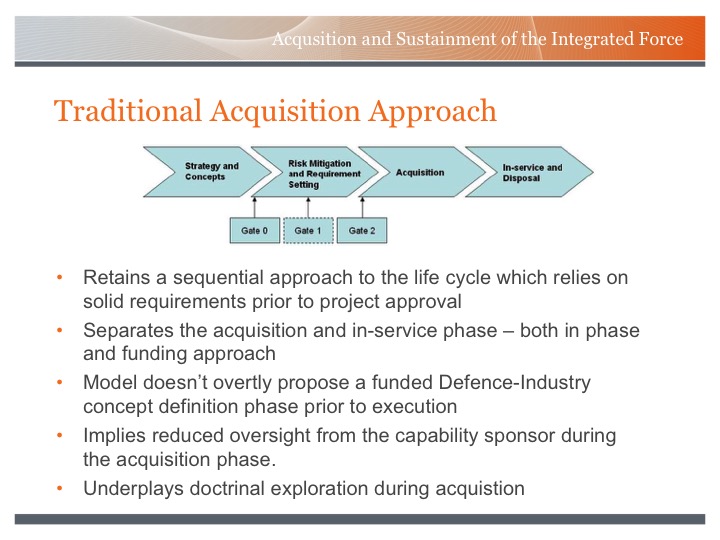

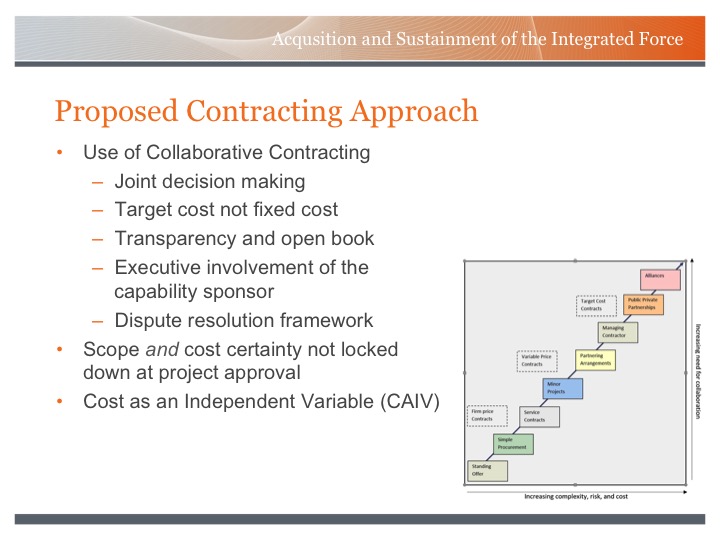

The presentation by Air Commodore Leon Phillips, Director General Aerosapce Maritime, Training and Surveillance, looked at ways to reshape the acquisition and sustainment of the integrated force to address some of the concerns raised by RADM Dalton.

In his presentation, Phillips contrasted the traditional project approach with what he referred to as a new engagement model to allow for more flexibility in development but ways to constrain cost and shape realistic outcomes.

Put bluntly, without organizational change it would not be possible to achieve effective ways to shape integrated design cost effectively and in light of the dynamics of software development.

To achieve a joint design outcome, it would be necessary to shape an engagement model in which industry was a full partner. It was crucial as well to feed learning back into requirements generation as well.

Slide from presentation by Air Commodore Leon Phillips, Director General Aerospace Maritime, Training and Surveillance, to Williams Foundation Seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017

Slide from presentation by Air Commodore Leon Phillips, Director General Aerospace Maritime, Training and Surveillance, to Williams Foundation Seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017

Budgeting changes were required as well.

“We don’t do enough funded work with industry to get a realistic assessment of the domain of the feasible nor with regard to how to price evolving options and capabilities.

“How do you price the evolution within the force of options and opportunities when you manage with fixed priced contracts? You don’t.”

He argued the new engagement model would divide programs into three phases: a partnership, appraisal and executive phase within which different approaches would be combined to deliver a capability.

This slide is taken from the presentation by AIRCDRE Leon Phillips, Director General Aerospace Maritime, Training and Surveillance. to the Williams Foundation Seminar on Joint Force Design, April 11, 2017.

This slide is taken from the presentation by AIRCDRE Leon Phillips, Director General Aerospace Maritime, Training and Surveillance. to the Williams Foundation Seminar on Joint Force Design, April 11, 2017.

In the partnership phase, one establishes the steering group and the stakeholders to be involved in program definition.

The focus is upon the vision or the wish list of the capability, which is the target of the effort.

In the appraisal phase, there are funded studies which allow education about what is realistic to achieve for the target funding and to shape choice and determine how to reduce risk.

In the execution phase, the core decisions have been taken and the target objectives defined and pursued. The execution phase adjusts the vision to realistic outcomes within the targeted budget. It is not about requirements it is about outcomes driven by the partnership as a procurement force.

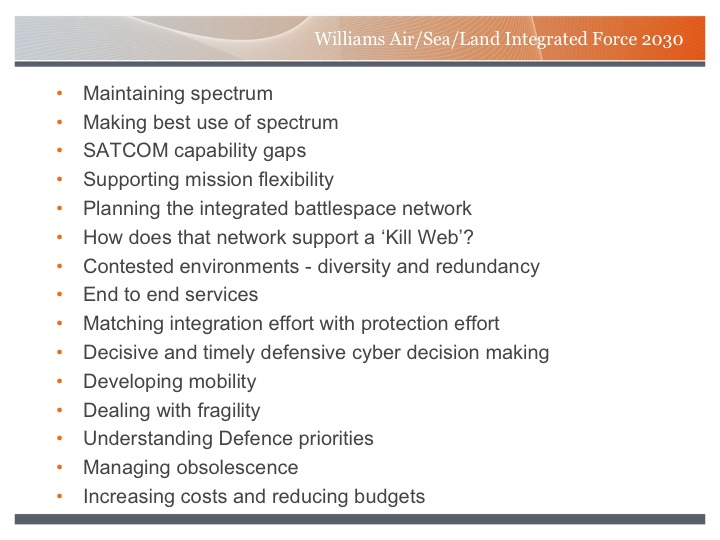

The final presentation addressed the challenges of the digital nature of the joint force.

How to best leverage dynamically developing IT and communication systems to deliver a force able to leverage a diversity of networks and to deliver a joint effect?

In his presentation, BG Wainwright defined how he saw this challenge:

“The range, array and potential of next generation sensor technologies – matched to long range, precision fires – will demand low signature land forces capable of operating well below an adversary’s detection and discrimination thresholds.”

“Which leads me to offer a note of caution: A highly networked and integrated joint force is one that may on one hand draw great strengths, but equally exposes real and rich targetable vulnerabilities to our adversaries. It is here that the lessons of the past also hold the key to preparing for our future.”

In the presentation by Air Vice Marshal Andrew Dowse, Head of Information Communications Technology Operations, a diversity of challenges facing the development of a proper set of glues for evolving force integration was the focus of attention.

One of the most interesting aspects of the discussion was the need to evolve the IT and Coms systems to support the ADF as its reach were expanded for the extended defense of Australia.

This meant that reach, security and flexibility were crucial to ensure that platforms were not flying blind and their contributions minimized by lack of an ability to leverage various networks.

“The proliferation of networks proliferates the risks.

“And this could affect the availability and contribute of very expensive combat platforms at crucial points in combat operations.”

Various networks is really the point.

It is not about everyone being on the same network: it is about shaping ways for force packages to integrate by leveraging discrete, diverse and flexible networks.

“Mobility is a serious consideration; we need to provide digital capabilities where the force operates.”

Shaping a Way Ahead – The Perspective of Air Vice Marshal (Retired) Blackburn

This seminar was different from the earlier Williams Seminars.

In the earlier seminars, the new platforms on air, sea and land transformation was discussed in detail and the service perspectives highlighted.

This seminar built upon these earlier presentations and proceeded with the question of how one would build by design more integration into such a force, rather than doing so after the fact.

After the seminar, I had a chance to sit down with John Blackburn and to discuss the challenges and way ahead in designing an integrated force rather than cobbling together platforms into a force, which is, integrated piece meal after the fact.

Question: The seminar looked at a very tough issue. US services are individually looking at service integration, rather than force integration. The seminar explored how one might design in joint force integration. Could you describe the approach used in the seminar, which might will anticipate how this would be done in practice?

Blackburn: The hypotheses were put together as a set of questions to give a focus for the discussion, and each of the presenters were asked to do two things.

One was to talk about their particular area and how it’s going to be a part of integrated force, but secondly, just test the hypotheses, or propose other ones if they thought they were better.

If we can agree a simple list of hypotheses, then we’ve got a really good starting point upon which to design the force. If we can’t, we end up having an argument right down in the technical detail levels.

That was the intent.

The other different thing about this seminar was that I was able to meet with the three service representatives and the joint staff together to discuss what we were trying to achieve, what the hypotheses were, what the question sets were, and so the presentations you saw from the three services and from the VCDF here, were not people just coming into a seminar and giving their separate views.

They actually set down as a team and discussed it, to make sure the way they were looking at the problem and what they were going to present was coordinated, and to some degree integrated.

This normally doesn’t happen at seminars. People get invited, and they all come up with a set of PowerPoint slides that usually their staff has produced for them, and they all give the standard story.

This didn’t happen in this case.

Air Vice-Marshal (Retired) John Blackburn at the Williams Foundation seminar April 11, 2017

Air Vice-Marshal (Retired) John Blackburn at the Williams Foundation seminar April 11, 2017

Question: For sure, what you usually get is what Piaget referred to as parallel play?

Blackburn: That is right and we wanted here was serious consideration of how we might actually design an integrated joint force to get the full combat effects which force modernization could deliver.

In this case, we chose one stars to make the presentations.

Why did we do that?

When you get three stars, or senior officers, making presentations, everyone sits there and listens, but the folks who actually have to design the future force and lead the teams that are doing it are the one stars and the colonels, the O-6s.

You can see that each of our service chiefs have a very strong future focus. Our Chief of Navy and the documents which he’s been writing, our Chief of Air Force talking about the change in the whole way of culture we have to do this, and our Chief of Army driving his force forward.

When you’ve got 240 people in the audience, and these are by and large, apart from the industry folks, O-7s, one stars and below, they collectively are the ones that are going to have to do the hard work on doing the design under the guidance of the senior officers.

What we were trying to do for the 240 people in that room was have a conversation at peer level. In other words, it’s peer-to-peer conversation. We, as a team, are going to have to address this.

That’s why we decided not to ask the service chiefs to speak. At the conferences, we’ll get the service chiefs, because they think it’s important to have the head of the organization speak. We think it’s important to have a conversation amongst those levels in the organization that are actually doing the design and the thinking themselves, so they can express some ideas. They can exchange ideas.

It also is a really good way to set up networks, because not too many people are going to go ring up the Chief of the Service after a seminar and say, “Hey, I want to ask you about your question.” It’s not that hard to ring up one of the one-stars who had a conversation and say, “Hey, I heard what you said.”

There were some important messages that came out from those one-stars that showed they were thinking deeply about the issue and talking to each other about it. That’s the way to get an integrated force.

Question: When we’re talking about a 21st-century integrated force and why that’s important, a lot of people’s minds go back to the network-centric warfare days, and that’s not what we’re talking about.

You clearly are not talking about connecting platforms after the fact and calling that integration.

How do you see the difference?

Blackburn: Let me go back to the difference between the two. I was head of strategic policy at the time and we worked with Admiral Cebrowski as he launched the NCW discussion. He told us “NCW is an idea which we are just getting out there. If 40% of what I’m saying ever comes true, that’ll be a fantastic result, because it’s an idea. It’s to get the language out there.”

The reality is, we’re never going to be totally network-connected. It’s not going to happen. It’s like saying you’re going to have unlimited bandwidth and everybody can actually connect without the adversary disrupting those networks. You’ve got to start with the idea. You’ve got to get people talking about it and to get the language out there into the debate.

Now where we’re at now is moving to the next stage, of applying a bit of thrust as one of the speakers said, getting on with building this, not just talking about it but building it.

We see elements of force integration in the United States, but the integration there is by service. There’s integrated force happening within Navy with NIFC-CA. The USAF is looking at their future, Aerospace 2030 Concepts. We have to follow the ideas in the U.S. but take one step further – to integrate the whole force.

Because we’re small, we might be able to take the step straight to JIFC, the Joint Integrated Fire Control idea for Australia. We want to learn from the U.S., follow it closely, but actually take a step which is hard for the U.S. to do because of its size, and that’s go truly joint by design.

Editor’s Note: AVM (Retired) Blackburn led a study on integrated air and missile defense to explore the boundaries of how design from the outset of integration for the force might proceed.

According to a piece on the Williams Foundation website:

The Williams Foundation conducted an Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) study between Sep16 and Feb17 to explore the challenges of building Australia’s IAMD capability and the implications for the Department of Defence’s integrated force design function.

The study was focussed at the Program level of capability.

The study incorporated a visit to the US for a month to explore the IAMD challenge with United States Defense Forces and Agencies, think tanks and Industry. The initial study findings were then explored in Australia in three Defence and Industry workshops on 31 Jan17 and 1 Feb 17, using a Chatham House model of unattributed discussions.

Many of the statements made in this report are not referenced as they are derived from these Chatham House discussions and associated meetings.

IAMD is a highly complex issue; comments made in this report should not be construed in any way as being critical of the IAMD approach of the Department of Defence. This report cannot account for the full complexity of the integrated force design process that is being addressed within Defence; however, it may offer some value in providing suggestions based on the study findings.

This study would not have been possible without the support and assistance of several areas within the Australian Department of Defence, the US Defense Department, Industry and think tanks. The Williams Foundation deeply appreciates the support of the IAMD Study major sponsors, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman. Thanks are also due to Jacobs in funding the services of Dr. Gary Waters who provided valuable support in the research for the study and in the production of the workshop notes.

This report represents the views of AVM Blackburn (Retd), the IAMD Study lead. This study report is intentionally high level and brief; in the author’s experience, long and detailed reports are rarely read by senior decision makers.

The study can be downloaded here:

http://www.williamsfoundation.org.au/resources/Pictures/WF_IAMD_ReportFinal.pdf

or here:

https://sldinfo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/WF_IAMD_ReportFinal.pdf