The Future Naval Service Posture and the Need for a Reinvigorated Revolt of the Admirals

By Vince Martinez

Here we go again…

07/25/2011 – It seems we are in familiar territory again—collectively diving head first into a looming post-war era of demobilization, retrofit and reset. Coupled with a decreasing defense budget, dwindling service structure and doctrinally driven acquisitions, each service is in a pitched fight to defend their operational relevance and their service posture.

Add a new Secretary of Defense, allegations of acquisitions concern over high visibility programs, a chasm of divergent doctrinal perspectives, and it is as if we are reliving the “Revolt of the Admirals” in 1949 all over again.

Only, this time around–while there is plenty of banter behind the scenes–one key element is missing: The public display of vocal discord against an emerging defense posture that does not sufficiently bolster the Navy and Marine Corps team for future success—much of which has been defined without the benefit of a well informed perspective from the Naval Service leadership in defense of their doctrinal roles and responsibilities to the nation.

The hallmark of the Navy/Marine Corps team as described in the doctrinal publication “Forward…From the Sea” in the early 1990s has been slowly dismantled over the last couple of decades–one piece at a time. It hasn’t been with a lot of pomp and circumstance, nor has is come with a tremendous amount of public knowledge or visible impacts.

But is has manifested in decreased budgets, long range shipbuilding strategies that de-emphasize our amphibious capabilities, and through ship designs that do not maximize what the Navy/Marine Corps team has to offer. With the senior defense leadership being focused on sustaining and fighting a ground fight over the past few decades, it is clear that the utility of Naval Forces and the strategic impact they bring to the fight has suffered from a lack of attention and visible support.

The Naval Services are finding themselves in a pitched battle to claim and define, once again, their importance within the overall defense posture. Its relative value, however, can be simply be measured by the materiel condition of the fleet.

What are the major differences from what the public saw in 1949? Not much in the grand scheme of things relative to service level doctrinal perspectives. What has changed, however, is the fact that the technology for both friend and foe has grown exponentially more capable, the threats are often distributed, much more lethal and elusive, and the roles and missions for the Naval Services have expanded exponentially into a much larger spectrum of operations—including operations like Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief. Coupled with an operational tempo that is stretching the seams of the services themselves, along with the fact that the equipment being employed by the warfighters is not being replaced at a sufficient enough pace to keep up with the demand, you have a recipe for some significant challenges for the Naval Services in the coming years.

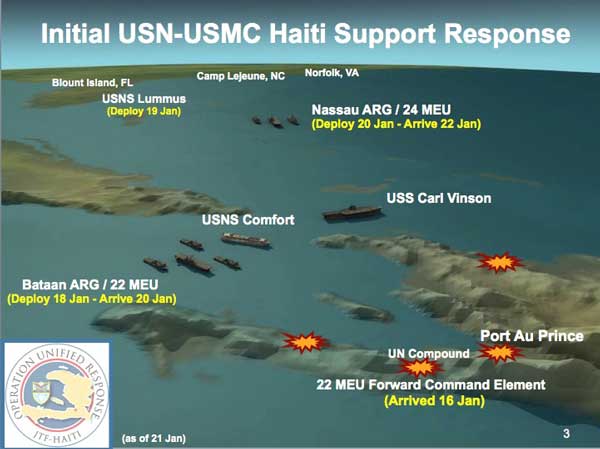

From Haiti deployment briefing Credit: USN (Credit: http://www.quantico.usmc.mil/Seabasing/docs/Haiti%20Collection%207.ppt)

From Haiti deployment briefing Credit: USN (Credit: http://www.quantico.usmc.mil/Seabasing/docs/Haiti%20Collection%207.ppt)

To illustrate the impacts of lack of attention to the amphibious side of the fence, the current fleet of amphibious ships is comprised of a very high number of ship design configurations relative to the overall number of ships, precluding Program Managers from effectively and affordably executing lifecycle management strategies.

Many of those ships are being worn out and retired faster than ships can be procured and built to replace them. Even the replacement ships, unfortunately, are being assessed and fielded with the same mindset—single ship/single class deliveries are being proposed as potential materiel solutions in order to bridge to yet another class of ship in the out years—a strategy, which of course, will only exacerbate the problem. Grey bottom shipping isn’t the only major challenge facing the Naval Forces.

Many of the aircraft, ground vehicles, ground systems and black bottom vessels that support amphibious forces are also nearing or surpassing their original service life—some of which have no tangible replacements on the horizon.

As a result, the naval services are continually having to hemorrhage resources to not only ensure their gear is sufficiently ready to satisfy not only their operational commitments, but also to facilitate a bridge to often troubled programs of record that are supposed to replace the legacy gear in the first place.

Amid all of that, senior leadership in the Pentagon and within the congressional hallways often contribute to the friction by openly razing emerging programs along with the vendors that produce them, while the vendors are struggling to get through the acquisitions wickets that have been placed upon them.

Rather than incentivizing industry, this type of response seems to only frustrate those on the industry side—many of whom will remain critical to national defense in terms of the design, development, manufacturing and fielding of the much needed new and innovative capabilities that will be essential for sustaining a technological edge to carry the services into the future.

While everyone holds a part of the blame for troubled programs, often times–and against conventional wisdom—many of the problems are not the result of industry side inefficiencies, as many in the Pentagon or in Congress would assert. As an example, much of the blame for the large number of amphibious ship configurations originates from the rapid and undisciplined requirements creep that comes at the hands of unconstrained requirements generation. This clearly has negative impacts on not only the manufacturer and the ability to efficiently produce a ship, but also creates issues for acquisitions and the fleet in terms of maintenance and lifecycle management.

This, and a litany of other programmatic challenges resident within the Naval Services–along with the programs that drive them–demands a new and innovative approach for assessing and defining not only current and future operational impacts, but also for setting the stage for effectively managing, executing and overseeing enterprise level acquisitions in support of Naval Services warfighting requirements.

In 1949, it was the lack of a coherent strategic message that ultimately led to the super carrier United States falling prey to the Air Force B-36 Bomber initiative during the service level loggerheads.

Today, as in 1949, the future outlook for many of the capabilities resident within the Naval Services are at risk against other service priorities because of the lack of a focused message that adequately spans across the entire naval enterprise.

Today, the list of naval programs that are having to fight for resources in order to affordably survive not only includes new-start ships the LHA replacement, but also other transformational capabilities like the F-35B Joint Strike Fighter or the MV-22 Osprey–which if truncated or cancelled will negatively impact the agility and the flexibility of the Naval Service as a whole.

Joint isn’t always the answer…

Despite the great successes over the years inside of the Joint arena, there are still many challenges that loom in combat operations despite the overwhelming technological advantage that our services hold. This becomes particularly acute as we begin to examine our current and future operational capabilities in the light of service doctrinal roles.

The Marine Corps, as an example, is now actively moving toward reestablishing its amphibious and expeditionary roots aboard naval shipping. When embarked, and furthermore when employed across the spectrum of operations, what has typically been readily available in terms of Joint fire support over the last decade—as an example—will no longer be readily available. The service, then, has to be prepared to address that and other capability shortfalls as part of its doctrinal responsibilities when embarked aboard the Amphibious Readiness Group (ARG).

It is this particular operational shortfall, which has driven the Marine Corps to define a requirement for the F-35B. In addition to that particular niche, however, the F-35B is capable of not only providing V/STOL Close Air Support (CAS) like its predecessor the AV-8 Harrier, but through the benefits of technological innovation, also provides enhanced force protection through kinetic and non-kinetic fires, provides Electronic Warfare (EW) capabilities to support the MAGTF in all phases of operations, as well as providing a critical enabler for the command and control at sea or ashore.

At the same time, it also brings the attributes of a 5th Generation Fighter along with it, which simultaneously enhances the force protection umbrella for the ARG. Despite the fact that many would argue those capabilities are resident within the Joint Services as a whole, even when those capabilities are available for tasking, they may not present a solution that best serves the operational, tactical and environmental conditions on the ground.

Case and point: for the first time since Vietnam, a living Marine–Corporal Dakota Meyer–will receive the Medal of Honor for his actions in Afghanistan in September, 2009. Corporal Meyer bravely raced into the kill zone of a firefight in the Ganjgal Valley to retrieve the bodies of three Marines and a Navy Corpsman who were killed by enemy fire.

While the award is a celebration of Corporal Meyer’s ultimate bravery, what will not be listed on his Summary of Action are many of the external conditions that led to his bravery in the first place; much of which was the result of a glaringly tragic operational shortfall. In the executive summary of the investigation into the incident in the Ganjgal Valley in Afghanistan on 8 September 2009[1], it was clearly noted that Joint fire support was available within the Coalition Joint Task Force (CJTF-82) during the operation, but “Timely aviation and indirect fire support were not provided.” The report also goes on to state that repeated requests for the Quick Response Force (QRF) were not supported, and that a lack of situational awareness, decisive action and a sister services “…lack of commitment to support partner units with the same focus and emphasis as organic units” contributed to the operational failure.

While it is not my intent to minimize this tragedy to just a few sound bites or to commercialize the loss of lives, what is clear is that the Joint fire support system broke down enough to contribute to the death of three Marines, a Navy Corpsman and an Army soldier—along with several coalition Afghan Soldiers—due to lack of dedicated, responsive fire support that could have reacted when they needed it most.

An organic, USMC F-35B in the mix could have made a significant—if not life saving—difference in terms of building situational awareness for the ground force and the Tactical Operations Center (TOC) before, during and after the attack. The F-35B could also have supported through decisive action and the delivery of kinetic and non-kinetic fires, or by providing multi-spectral support prior to the operation to inhibit or deter the enemy’s desires to do harm in the objective area prior to the coalition troops ever arriving. Want to know why the Marines want and need the F-35B? Look no further than the loss of life in Ganjgal Valley.

Defining and Defending a New Way Forward…

While the challenges for the Naval Service span a vast array of systems and capabilities, the struggle for senior defense officials is often in taking tangible lessons from war and applying them directly toward the acquisitions, planning programming and budgeting, and requirements generation systems. The F-35B is only a single example of a programmatic struggle that is occurring because of the lack of a well-defined, Navy and Marine Corps strategic message.

Without a strong, cohesive voice from the “Admiralty and Generalship” of the Navy/Marine Corps team, the ability to counter the advances of senior defense official decision makers who are attempting to fill a perceived hole becomes very difficult.

As a result of the lack of a strategic Naval Service message, the Navy/Marine Corps team will likely have to continue to accept decisions that directly impact the warfighter—at sea and ashore—because they have not had the opportunity to prep the battlefield sufficiently as a team in order to win the day.

It is high time for the Navy and the Marine Corps team to tackle these issues in a cohesive manner—especially relative to the amphibious forces—and portray the strategic nature of the Naval Service as a whole in a light that defines and defends a strategic role now and in the future.

It may be time for a re-visitation of the Revolt of the Admirals. This go-around, however, has to be the byproduct of a cohesive Navy and Marine Corps team. The Naval Services cannot afford to repeat history when it comes to today’s fight for resources, and they must be diligent in their pursuits to ensure the safety and stability of the nation they serve.

Changing the way the Naval Services define, field, fund and fight their collective operational capabilities is the only way to do this effectively. In the hallways of the Pentagon, it can no longer just be the about the Blue or the Blue supporting Green budget verses the Green Dollar budget. It can no longer be about unconstrained requirements generation or acquisitions program baselines that sacrifice capabilities for cost, schedule and performance without much needed input from the warfighters.

Through disciplined, inclusive and holistic alignment of capabilities across the amphibious force—as well as all the integration of all the elements that feed them—the overall operational impact of the Naval Forces has to be captured in a way that makes programmatic, budgetary and operational sense for the Naval Forces as a whole.

Make no mistake about it—even within the Naval Services—many will profess that this type of initiative will be extremely difficult to create, much less result in a balanced and effective set of solutions to present to the senior defense leadership.

Now is as good a time as any, however, to move on a strategic change of direction. It is time for the leadership to chart a new course in the development of the synergistic roadmap that define their collective futures—one that ensures the collective well being of the Naval Services as a whole.

An innovative, cross-functional and disciplined approach for doing exactly that has to be developed and implemented in the near term in order to ensure these service level challenges are addressed.

What everyone also knows, however, is that this type of innovative approach will only be possible through the vision, leadership and desire of a restless Generalship and Admiralty who recognize and know that it is high time for another Revolt of the Admirals.

[1] http://www.scribd.com/doc/27077099/Ganjgal-Report