2013-11-22 by Robbin Laird and Ed Timperlake

Dateline Los Angeles: The AFA Pacific Forum

A key challenge in any major relief effort is putting together an effective infrastructure from which to support a relief effort.

A massive disaster like Katrina or Typhoon Haiyan by definition destroys everything in its path and this means the infrastructure from which normal life is supported.

This requires the crafting of a substitute infrastructure from which to generate support. It is not widely understood that this is a core competence of the USAF.

Earlier we looked at how the USMC was tasked to assist with the MEF/MEB roll in and the aviation capabilities of the Osprey-KC130 twining provided for early intervention capabilities.

In our interview with Lt. Col. “Sniper” Brown, he highlighted the similarities between what he saw in the Philippines with what he saw when working New Orleans relief.

“When I first prepared to land in both situations, what I saw was things I was used to seeing simply gone. That was the baseline from which you worked.”

We had an opportunity to sit down with Col. Douglas James, from PACAF who was attending the Air Force Forum on the Pacific in Los Angeles, along with his boss, General Hawk Carlisle. James is on the operations staff of PACAF and has been working on preparing and executing support for the effort from before the time the Typhoon struck.

We learned as well that James had had the same reaction as Brown with regard to New Orleans.

“I was a reservist and flew in the second commercial plane into New Orleans after the Hurricane hit; in some ways it was just as bad as Typhoon Haiyan. I think it is difficult for someone who has not experienced this to know just how daunting it is to launch a relief effort when everything is simply gone.”

The focus of our discussion was upon how the USAF has intervened to shape the infrastructure to launch a relief effort.

The visuals are usually of the planes coming in and delivering supplies and moving people into or out of affected areas.

The planes surely are important, but neglected is the role of the lay down of infrastructure to allow for the flow of goods and support into the affected areas.

A key tool for the USAF is their crisis response groups or crisis response wings.

Earlier, Second Line of Defense visited one of the two worldwide CRWs, this one is in New Jersey and the one which deployed to the Philippines was based in Guam.

In discussing the role of the USAF in the Pacific in an earlier piece, we highlighted the important role which this capability can play.

As General Allardice put it:

Another key piece of the global enterprise is our two air mobility operations wings.

They support the enroute structure, 16 main enroute locations and numerous other bases operating worldwide in the Pacific, throughout Europe, and in the Mideast.

It’s a fairly lean organization, ranging from small, two-person detachments all the way up to robust squadrons.

They’re the ones that catch the airplanes, refuel the airplanes, and fix the airplanes. If a crew needs rest, they’ll make sure there’s billeting for them, and they’ll run a crew stage.

Simplistically, what I say is they accelerate the flow of iron throughout the world.

The CRWs are made up of a variety of small teams, but in many ways the crown jewel is the contingency response group.

These are the expeditionary groups that can go out and open up a bare base anywhere in the world. They are self-contained organizations, about 110 people.

Their whole purpose is to act as a forward hub so that our airplanes can flow in, perform their mobility mission and flow back out again.

Col. James underscored the central role of the CRG in the USAF role in the Philippine relief effort.

“They deployed to Tacloban and worked to open up the airport to become capable of flowing in support capabilities. They had to set up air traffic control support; they had to work to extend the runway from 4500 feet to more than 8000, they worked with the Fillipinos to make sure the kind of safety equipment we needed to maintain sortie rates was available to ensure safety and security. They also focused on getting in the machinery which can facilitate offloading of supplies.

Getting a forklift into play was important as well.”

James highlighted that the initial team came with C-17 support with the plane able to land on the 4500 feet of available space.

“We do this all the time at Quantico to move the Presidential helicopters; so that is what they did here. But by and large, Tacloban is being used by C-130s.”

As we highlighted in our visit earlier to the CRW in New Jersey, the team operates the equipment for handling supplies and materials when forward deployed. During that visit, we discussed with the airman how this works:

Ruiz: Here are a couple of pieces of equipment that we use to transport loads to and from the aircraft, and around our yards. Basically, all the loads are on a pallet that’s right on top. And you can see our new generation small loader. The newest K-loader that we have is capable of carrying 25,000 pounds.It’s named after Mr. Albertson, who was the candy bomber during the Berlin Airlift.It can carry up to three of those pallets, either logistically or at ADS, basically there’s a short side and a long side to each one of those pallets.

SLD: The loader is designed to be air mobile and to then function to load or unload transport aircraft on location?

Ruiz: Yes, sir. They are used on location. It’s actually highly deployable as well; it only takes about 30 minutes to get this ready to put on an aircraft. So, in the CRW world, it actually works out very well.

SLD: And obviously, it goes fairly flat then?

Ruiz: They can go down to about 39 inches, and it can also be raised to about 220 inches. It also has a pitch and lift, so when we bring it up to a type of aircraft, if we’re unequal or unsteady by some weight, we can straighten it out.

SLD: So, you can bring it out of pretty much of anything that would fly?

Ruiz: Roger that, sir.

SLD: What fuel can the K-loader operate on?

Airman Baxter: JP86 diesel, and sometimes kerosene. All the newer style fuels as well. The vehicle will run off of anything you can find at an airfield.

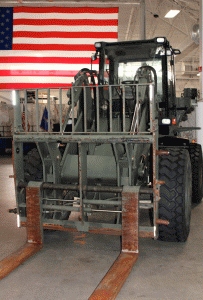

SLD: You have explained the K-loader and we are now looking at fork lift, could you tell me something about this vehicle?

Ruiz: This is the 10K AT fork lift, and we usually just use one pallet, 10,000 pounds. No more than 10,000 pounds. It’s all-terrain vehicle, that’s what the AT stands for. It can pretty much go anywhere. I’ve had it in about six feet of water and mud, and it ran fine.

SLD: In water and mud?

Ruiz: Yes. In a swamp, trying to pick up some pallets that we dropped. This is the bread and butter of what we do, sir. This is pretty much one of our primary vehicles. We have bigger ones called 60Ks, up to 6,000 pounds, but they’re not as mobile as this is. Like I said, this only takes 30 minutes and we’ve got it on the plane. The 10K AT is how we move all of our cargo to and from after we get it off the aircraft; this is what moves everything around in the airfield.

This capability discussed in New Jersey was highlighted by Col. James as part of the USAF capability to build the crisis response infrastructure.

James argued that Clark Airbase was another key area, but this facility in effect functioned like the FEDEX hub in Memphis.

“Supplies would come in from Hawaii and elsewhere, and be processed at Clark for movement throughout the island chain.”

A key challenge was managing the diversity of coalition air traffic as well.

But here the experience in Afghanistan has proven useful as well:

“The diversity of multinational traffic coming into the Phillipines for relief support was similar to managing coalition traffic with CENTCOM, where I have had previous experience.”

James also highlighted the importance of getting functioning communications systems where needed, and here the USAF is very skilled in bringing in mobile support equipment to provide for communications capabilities as well.

During the visit to the CRW in New Jersey, a core competence of the team is its ability to bring in mobile communications equipment and standup capabilities within a very short period of time. In the Philippines relief effort, this competence was in demand.

Another key contribution of PACAF has been to provide what might be called distance support to forward deployed air elements, including for the USMC.

“There was a need to calculate things like safety and security requirements for the deployed force; they did not have the capabilities or time to deal with this kind of requirement. We calculated this for them and then communicated our recommendations to them in the field.”

Normally, the USAF does testing to prepare for a rapid runway repair contingency, but the largest storm on the globe slamming the Philippines gave the immediate requirement-“this is no drill.”

Runway, repair, dangerous FOD (foreign object damage-from lose items on a runway) to lessons learned in blood having as mentioned above crash and rescue standing ready all became the often overlooked focus of a successful air operation.

The partnership with Philippine forces on the ground, mirrors the USMC experience.

It is their country and they were grateful for help and they had a sense of dedication that was commendable.

It was a true partnership formed among nations to assist local “can do” Philippine forces and civilians engaged in disaster relief.

The Colonel underscored that multiple exercises across the Pacific with joint partners as U.S. friends and allies helped smooth out these operations.

Moreover, he highlighted that the USAF was serving as both as part of the larger joint effort supporting US AID and to the Philippine government.

“The Philippine government was working the challenge of coordinating incoming aid efforts; our role was simply to support this effort. They have done a great job under unbelievable duress.”

| Col Doug James Deputy Assistant Director of Operations |

|

| Colonel James received his commission in 1987 through ROTC at Brigham Young University. He transferred to the Air Force Reserve in 2001. He first served as an A-10 pilot and then flew the F-15. During a Pentagon tour, he managed the A-10, F-117, Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle, and the Advanced Targeting Pod programs. He also worked on USAF’s Legislative Liaison Staff. Most recently he finished a four-year active duty tour as Deputy Director of the Coalition Coordination Center, US Central Command. | |

For additional background on the USAF within the overall relief effort, see the following:

http://www.pacaf.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123371023

http://www.pacaf.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123371786

U.S. Air Force Fact Sheet

| 36TH CONTINGENCY RESPONSE GROUPThe mission of the 36th Contingency Response Group is to train, organize, equip and lead cross functional forces providing initial Air Force presence potentially austere forward operation location as directed by commander Pacific Air Force.The 36th CRG incorporates more than 30 different jobs into one close-knit team. It is a rapid-deployment unit designed at the initiative of Air Force leadership to be a “first-in” force to secure an airfield and establish and maintain airfield operations. The 36th CRG was created specifically to respond to the growing number of fast-moving contingency deployments today’s Air Force experienced in the Western Pacific.Although typically tailored for a specific mission, the CRG is postured to deploy all or part of a 120-person team of more than 30 specialties with no more than 12 hours notice. The 36th CRG is designed to be a multidisciplinary, cross-functional team whose mission is to provide the first on-scene Air Force forces trained to command, assess, and prepare a base for expeditionary aerospace forces. The cross-functional design under a single commander provides a unity of effort while also minimizing redundant taskings or personnel. This in turn allows the unit to be trained to task and ready to deploy rapidly–all with minimal equipment and personnel.The 36th Contingency Response Group is comprised of the 36th Mobility Response Squadron, the 554th RED HORSE Squadron, the 644th Combat Communications Squadron, and the 736th Security Forces Squadron. |

Tacloban Air Base is the hub for aid going into Tacloban, Republic of the Philippines and for evacuating victims of typhoon Haiyan.

The video above provides a time lapse look at activity on the airfield seen on 11/17/13.

Credit:III MEF:11/17/13

Editor’s Note: The USAF has developed a unique force package called the crisis response group, which is designed to fly to the challenge of building infrastructure to allow for the throughput of airpower to follow. This is done for both Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Relief missions and to support military operations.

In the recent Philippine relief effort, the USMC and the 36th CRG worked closely together at the Tacloban Air Base to put in place an infrastructure to support broader relief efforts, and then within two weeks left to allow the civil authorities to take full charge of the efforts.

In the slides below, the basic structure of the 36th CRG is outlined along with some of its recent activities.