In his August 2 speech before a Disabled American Veterans conference in Atlanta, President Barack Obama said that the American role in Iraq was transitioning from Operation Iraqi Freedom, a military effort led by U.S. combat troops, to Operation New Dawn, a civilian mission run by U.S. diplomats based at the Baghdad Embassy.

The President reaffirmed that he would meet his campaign vow to end the U.S. “combat” role in Iraq by the end of this month. For 18 months after that, some 50,000 American soldiers will engage in a transitional mission of training, advising, and equipping Iraqi forces as well as working with them to fight terrorism and protect civilian economic reconstruction projects. Obama restated that all U.S. soldiers will leave Iraq after 2011, when the current security agreement negotiated in 2008 between Washington and Baghdad authorizing their presence expires. This withdrawal would leave U.S. embassy personnel, periodic joint U.S.-Iraq troop exercises, and large numbers of American contractors to support past and future arms sales as well as other services as the main U.S. military contributions to Iraq in 2012 and beyond.

President Obama also made clear that his administration plans to prioritize Afghan War needs when deciding where to send U.S. military personnel, equipment, and supplies for the remainder of his first term. Although this speech was billed in advance as a presidential statement on his Iraq policies, Obama actually spent more time defending his Afghan strategy—as well as quite properly thanking the veterans for their service—than explaining the administration’s future approach toward Iraq. While the number of U.S. troops in Iraq has sharply declined since Obama assumed office in January 2009, a figure that should exceed 90,000 people in a few weeks, the number of American military personnel in Afghanistan has surged from 33,000 to almost 100,000.

One reason for his prioritizing Afghanistan was that the situation in Iraq now looks much better by comparison. Although Iraq is a more important country by most objective measures (population size, value of natural resources, regional influence, etc.), the Iraq security forces have managed to perform much more effectively than their Afghan counterparts, though Iraqi and U.S. sources disagree about the level of violence still plaguing the country.

Last month’s international conference in Kabul set 2014 as the date when the multinational coalition supporting the Afghanistan plans to transfer many domestic security tasks to Afghan government forces. But even this late date seems premature given the currently weak state of the Afghan National Army and National Police. There were 66 American casualties recorded in Afghanistan in July 2010, the highest monthly total ever.

In contrast, since July 2009, when the Iraqi government assumed responsibility for ensuring security in the country’s urban areas, the American combat forces in that country have stayed mainly in the background. They now mostly provide intelligence, advice, and logistical support to the approximately 700,000 Iraqi military and police personnel, who have assumed the most prominent security roles in their country. In principle, Iraqi commanders have had to approve every major military operation conducted by U.S. forces in their country. These operations have included joint patrols between U.S. and Iraqi forces, a practice that has helped suppress the sectarian, ethnic, political, and other divisions among the Iraqi security personnel. Some of these joint patrols, such as around the explosively contested city of Kirkuk, should continue for at least the next year. The success of their transformed role has already allowed tens of thousands of U.S. troops to leave Iraq without evoking much alarm or even drawing much attention.

That said, the security situation in Iraq, while not dire, remains troubling. Last month’s suicide attacks and car bombs in Baghdad, Baquba and Karbala killed some 170 people. The spokesman for the U.S. forces in Iraq, Maj Gen Stephen Lanza, said a total of 222 people died in July 2010 due to terrorist actions. According to Iraqi sources, at least 535 people were killed last month, the highest level of violent deaths for more than a year. Some observers worry about a possible revival of al-Qaeda in Iraq, which appeared largely defeated following the surge in U.S. forces in Iraq in 2007 and 2008.

Although joint Iraqi-U.S. military patrols continue to kill or capture a few al-Qaeda in Iraq leaders each month, the organization rapidly finds replacements. Rumors persist that some Iraqi security forces have also tacitly supported the bombings as part of the maneuvering for political influence in the country, perhaps to discredit the current government or induce U.S. troops to remain longer than planned. Many police units are lagging behind their army colleagues in training and performance, requiring the 250,000 Iraqi army personnel to man urban checkpoints searching for bombs and terrorists rather than patrol Iraq’s international borders. A lack of high-level leadership of the security forces due to the inability of Iraqi factions to form a new government may be compounding the problem.

This is indeed the main uncertainty at present—which parties will form the next ruling coalition and which individuals will occupy the key posts of Prime Minister, President, and the Minister of Interior. Despite the delayed holding of the national legislative elections on March 7—the original intent was for them to occur last December—Iraq’s political leaders have yet to form a government. The failure of a single party to receive anywhere near a 163 seat majority of the 325 contested parliamentary seats—the two highest party vote totals were 91 and 89—reflects the pluralistic nature of contemporary Iraqi society. The decision to employ an open-list system, which permits voters to cast ballots for individuals no matter where they rank on the party lists, has further weakened the role of Iraqi political parties. As a result, the personalities involved matter much more than their nominal party affiliation. Whatever the winning candidates said or did during the election campaign to become deputies in the new national Council of Representatives also matters little since they are now free to form new legislative coalitions and allegiances.

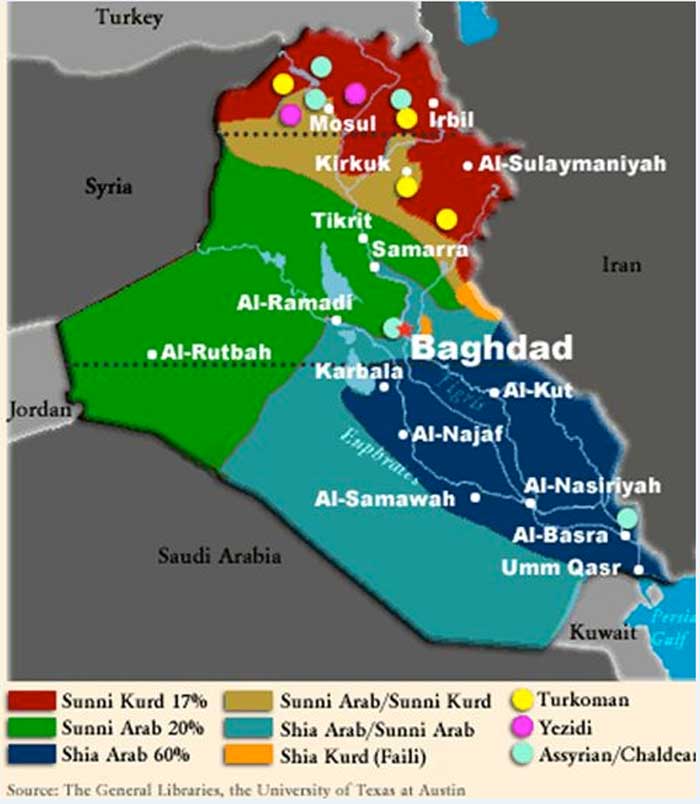

Iraq’s Ethnic Divisions (Credit Photo: The University of Texas at Austin, General Libraries)

Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has been using the advantages of incumbency to remain in office despite the close second-place showing of his primarily Shiite State of Law coalition behind that of the Iraqiya coalition led by former Prime Minister Ayad Allawi, who secured the support of many of the Sunni minority as well of Iraq’s Shiite majority. After months of political maneuvering and coalition dealing, neither man has been able to put together a majority governing coalition. The third and fourth place finishers—the Iraqi National Alliance of Shiite religious parties and the Kurdish coalition—have so far refused to commit to a government led by either Maliki or Allawai, while the latter two men have declined to accept an alternate compromise candidate. Since Iraq will soon enter the holy month of Ramadan, which starts in mid-August, it might not be until the fall that a new coalition finally arises, by which time Iraq will have a new U.S. ambassador in place of Chris Hill and another U.S. military commander to replace Gen. Ray Odierno. When it took six months to form a government after Iraq’s previous national election in 2005, the country slid into anarchy and civil war.

In addition to the security complications, the lack of a functioning government has impeded the development and implementation of coherent economic and other domestic policies. The constant electricity shortages, the stagnating oil production, the unattractive investment climate, the poor public services, and other economic problems threaten to undermine support for Iraq’s democracy before it takes root. Pervasive corruption has already worked to decrease foreign investment and aid, while mismanagement has thwarted efforts to transfer U.S.-funded projects to Iraqi government control. The UN Security Council is awaiting the formation of a government in Baghdad before voting whether to remove the international sanctions imposed on Iraq following its 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

U.S. officials have urged the Iraqis to accelerate their political efforts but have refrained from trying to force the issue or expressing preference for any particular leader or group. They have properly sought an inclusive coalition. Although some observers might at this point embrace any government that finally takes share, it is important that Iraq’s important religious and ethnic minorities—including the Sunnis, but also the Kurds, Turkmen, and perhaps others—feel fairly treated. Iraq’s minority groups need to believe that they will enjoy some influence over future government policies or they will become an alienated and perhaps violent force in the country’s politics. For this reason, it would be best if Iraqi governing coalitions included Kurds, Sunnis, and other non-Shiites in more than token positions to avoid further weakening inter-ethnic harmony in Iraq’s still fractured and traumatized society.

It is also clear that the current Iraqi constitution needs to be amended soon to clarify certain ambiguities, such as that the party the wins the most votes in a national legislative election receives the first opportunity to form a new government. Another needed change would require that incumbents relinquish office after a certain time rather than remain indefinitely in power, which encourages them to impede the formation of a replacement coalition. In addition, a revised constitution should mandate the holding of new elections if a government cannot be formed after six months or so. Amendments should also weaken the power of the Prime Minister, perhaps by enhancing the powers of the Presidency over foreign and defense policy. With two important positions available, Allawi and Maliki would be able to share power equitably in a joint government rather than fight viciously for the uniquely influential post of Prime Minister.

Yet, the March 7 parliamentary elections have confirmed Iraq’s status as a functioning democracy in which multiple candidates and political parties compete for office in accord with international standards for free and fair elections whose outcome cannot be predicted beforehand. Neither incumbency, nor tribal loyalty, nor sectarian affiliation determined the results of this March’s voting. Domestic and international observers, including those representing the United Nations, found no evidence of pervasive and serious fraud that might have substantially affected the outcome. If Allawi becomes Iraq’s next Prime Minister, or if someone besides the two current front runners heads the next government, Iraq will have marked an important democratic milestone, becoming one of the few Middle Eastern countries to have replaced its leader and ruling party through peaceful national elections. If Maliki remains in power, Iraq would still have had its most democratic election in history.

Although the future of the U.S. military role has become clearer, and democratic principles and practices still seem to enjoy the support of large number of Iraqis despite the frustratingly protracted process of forming a coalition government, other dimensions of the post 2011 Iraq-U.S. relationship remain opaque. The Obama administration has yet to specify what role Iraq will play in future U.S. policies toward the Middle East or with regard to many other dimensions.

Before leaving office, the Bush administration signed a November 2008 strategic cooperation agreement with the Iraqi government that committed both countries to maintaining extensive political, economic, energy, and cultural ties. Obama administration officials have not yet explained how they will implement this agreement, other than to release a statement on March 27, when the Independent High Election Commission certified the March 7 ballot, that, “The United States will continue to work closely with all Iraqi leaders to build a long-term, multi-dimensional relationship between our two nations.”

The future U.S. economic role could prove especially important. Many Iraqis tell media interviewers and opinion pollsters that they their main grievances are economic. The new Iraqi parliament needs to enact long-delayed energy, investment, and tax laws. In particular, Iraq and U.S. officials need to cooperate to ensure the continuing revival of Iraq’s energy sector, the anticipated source of many future jobs and government’s revenue.

This partnership could prove difficult. On the one hand, the United States does not want to appear as if it is seeking to plunder Iraq’s hydrocarbon wealth for its own benefit. On the other hand, it would not help future bilateral relations if, as in Afghanistan, the main result of so many U.S. and Iraqi deaths is to make the country safe primarily for Chinese state investment.

Iraq’s relations with its important neighbors also remain unclear. The elections saw a disturbing pattern of internal-external alignments in the country. Exploiting the lack of a law restricting foreign political financing, Iranians provided considerable support for Shiite-dominated parties, especially the faction led by the anti-American cleric Muuqtada Sadr, while the more secular parties received substantial assistance from sources in Turkey, Syria, and the Persian Gulf.

Allawi, whose backers include a large number of Sunnis alienated from Maliki’s government, has expressed interest in strengthening Iraq’s relations with other Arab governments whose ties are also strained with Maliki’s government, which is perceived as close to Iran. One of the first acts of the new Iraqi parliament should be to enact legislation restricting election contributions from non-Iraqi sources.

Weitz also discussed this issue on C-SPAN’s Washington Journal.

———-

***Posted on August 17th, 2010