The Missing Element from the “Sustainment” Debate

By Dr. Robbin Laird

08/01/2011 – In the wake of the headlines about the trillion-dollar airplane, F-35 sustainment costs have been tossed into the political fray. According to a single line in an unreleased SAR report, the F-35 fleet is projected to cost more than a trillion dollars to operate over the span of the life of the entire fleet for more than 30 years.

Less amazing than the number is the assumption about the assumption – that it reflects anything remotely relevant to reality. But in the current political climate of financial populism, the F-35 has become the poster child of the desire of many to withdraw from global engagement or more to the point from the modernization of the power projection force.

The F-35 B has been put on probation rather than lionized as a system which doubles the number of capital ships available to the USN from the Gator navy. Rather than emphasizing how the F-35B and the newly enabled ARG provide strategic relevance to the Littoral Combat Ship, the Administration and the Congress pursue every platform fights alone strategy and highlights IOC costs of platforms versus their operation as a fleet and their synergy with the force.

It is particularly ironic that the sustainment costs of the F-35 have entered a policy debate, hitherto never informed by logistics or sustainment issues. The Afghan war is the logistics and sustainment war par excellence, and can any of the “new” experts on aircraft sustainment, tell us the cost per year of logs and sustainment in the far away to reach war?

This is clearly simply a new tactic to eviscerate Air Force, USN, and USMC modernization, rather than a serious debate. As Adam Hebert, Editor in Chief of Air Force Magazine has recently argued:

Take a deep breath, everybody. The trillion-dollar operation and maintenance cost everyone is hyperventilating about is hardly worth the paper it is printed on. It counts every possible cost to operate and modernize the F-35 during a 25-year production run, followed by a 30-year operational life. It represents a half-century’s worth of fuel, parts, upgrades, and even related construction costs.

This time horizon extends until 2065. What makes the estimate particularly worthless is that it is computed in “then-year” dollars—an estimate that measures cost not by 2011 standards, but by what they will cost in the year they are spent. This includes 55 years of inflation at the tail end of the computation, an enormous multiplier that is especially damaging because all of these costs are still, psychologically, perceived as 2011 dollars.

All one has to do is think about the references to what a gallon of gas or a loaf of bread cost in some long-past year to appreciate the effect of decades’ worth of inflation. Just as 2065 is 54 years in the future, 1957 is 54 years in the past. The iconic 1957 Chevrolet cost roughly $2,500 at the time, while the average paid for a new car today is more than $28,000. Decades of compound inflation do amazing things, and anyone who claims to know what inflation rates or fuel prices will be 25 and 50 years hence is a fool.

And one could add that the current obsession with projected life cycle costs rather than real analysis is also part of the problem. Trying to predict the costs of future parts and of fuel and other variables is difficult because precisely they are variables. Using such indicators confuse decision making; they do not inform it.

Closer at hand are ways to understand how new platforms provide ways for enhanced maintainability. New platforms are built with a significant amount of attention to how to enhance their ability to be maintained over time. When platforms were built thirty years ago, logistics support was an afterthought. No it is a core element of determining successful outcomes to the manufacturing process.

Additionally, one needs to buy Fleetwide. Savings will come from pooling resources, something that cannot happen if you buy a gaggle of aircraft, rather than operating a common fleet. Just ask Fed Ex what commonality for their fleet delivers in terms of performance and savings.

The F-35 is strong on both points. The plane has been designed to optimize maintainability and to reduce the amount of touch labor on the plane by at least 30%. And the fleet commonality will lead to significant ability to operate, deploy and sustain fleets of aircraft.

Recently retired head of Marine Corps Aviation General Trautman hammered the first point home.

Affordability is the balance of cost and capabilities required to accomplish assigned missions. For over a decade the Marine Corps has avoided the cost of new procurement during a time when the service lives of our legacy aircraft were sufficient to meet the missions assigned. However, in the near future, our investment in the capabilities of the F-35B will outweigh the unavoidable legacy aircraft operations and sustainment (O&S) cost increases we will incur with the F/A-18, AV-8B, and EA-6B.

The O&S costs of legacy aircraft across DoD have been increasing at an average rate of 7.8% per year since 2000. The operational lifetimes of legacy aircraft are being extended well beyond their original design limits. As a result, we have been continually engaged in a struggle to maintain operational readiness of our legacy aircraft due largely to the increasing age of the aircraft fleet. Early in an aircraft’s life cycle, the principal challenge is primarily attributed to the aging proprietary avionics systems upon which the user depends for warfighting relevance; later it is maintenance of the airframe and hardware components that are become the O&S cost drivers.

The Marine Corps strategy for the last eleven years has been to forego the procurement new variants of legacy aircraft and continuing a process of trying to sustain old designs that inherit the obsolescence and fatigue life issues of their predecessors. Instead, we opted to transition to a new 5th generation aircraft that takes advantage of technology improvements which generate substantial savings in ownership cost. The capabilities of the F-35B enable the Marine Corps to replace three legacy aircraft types and retain the capability of executing all our missions. This results in tangible O&S cost savings.

A common platform produces a common support and sustainment base. By necking down to one type of aircraft we eliminate a threefold redundancy in manpower, operating materiel, support services, training, maintenance competencies, technical systems management, tools, and aircraft upgrades. For example:

- Direct military manpower will be reduced by 30%; approximately 340 officers and 2600 enlisted.

- Within the Naval Aviation Enterprise we will reduce the technical management requirements the systems requiring support by 60%.

- Peculiar Support Equipment will be reduced by 60%; down from 1,400 to 400 line items.

- Simulators and training support systems will be reduced by 80%; five different training systems will neck down to one.

- Electronic Attack WRA’s will be reduced by 40% and replaced with easier to support state of the art digital electronics.

- The Performance Based Logistics construct will nearly eliminate macro and micro avionics repair, and intermediate propulsion support functions.

- Airborne Armament Equipment (AAE) will be reduced by over 80% with the incorporation of a multi-use bomb rack.

- Compared to historical parametrics we expect our overall O&S costs to decrease by 30%.

The key to enabling these reductions is to evolve our supportability concepts, processes and procedures instead of shackling ourselves to a support infrastructure built for legacy aircraft. We need to be innovative and ensure our sustainment posture keeps pace with technology advancements and global partnering synergies. Working together with industry, the Marine Corps is intently focused on the future as we seek innovative cost effective sustainment strategies that match the game changing operational capabilities resident in the F-35 Lightning II.

The impact of fleet operations was highlighted by retired General Cameron, now working on the F-35 program with Lockheed Martin. Cameron as a retired USAF general in charge of maintenance highlighted the fleet consequences of shifting form F-16s to F-35As for the USAF.

The real beauty of the F-35 program is the fact that you can look out across the entire fleet, all the international partners, all the domestic partners, and tell immediately if there are systemic fleet wide issues. The program can share assets to ensure a surge capability to wherever it’s needed and can share the robust supply chain that’s already established on the F-35 production line. Our experiences with the F-16 highlight another major advantage of the F-35 approach. The F-16 has been a highly successful program. However, configuration management has been a challenge because it has been handled at the individual service level. Therefore, there are roughly 130 configurations of the F-16. The operators, when prosecuting the air battle, have to know the precise configuration of each F-16 in order to know what capabilities it brings to the fight. The sustainment of the F-16 is even more challenging with spares not being interchangeable among F-16 variants. The F-35 is a common configuration so interoperability is the key in both operations and sustainment.

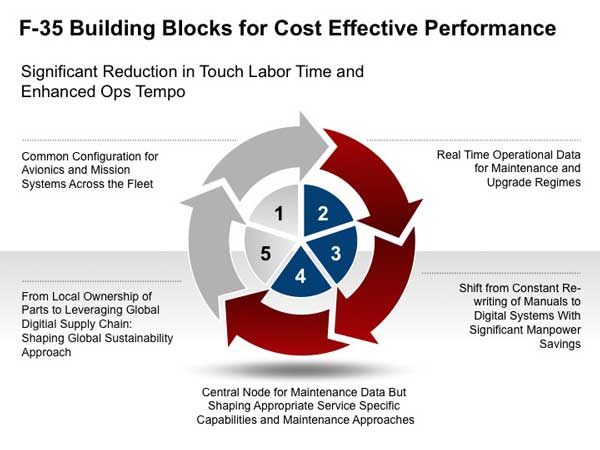

One could simply note that the views of such warfighters are simply bypassed in making wild assumptions about future life-cycle costs. An alternative approach would be to examine how the F-35 as manufactured leads to significant REDUCTIONS in touch labor time and to ENHANCED operational tempo which in turn lead to COMBINED reduction in maintenance costs with enhanced combat efficiencies.

There are several key elements of the game-changing approach to maintenance and sustainability literally built into the aircraft.

First, there is a common configuration for avionics and mission systems across the fleet. Rather than having to train and supply maintainers for multiple configurations of F-16s training and supply can focus on the common F-35A configuration. This is true of the other variants of the F-35 as well.

Second, the aircraft will provide real time operational data, which will allow maintenance to need rather than maintenance, based on paper determined schedules. The real time operational data will be used as well to determine parts reliability, which in turn can lead to improved design and production of parts, which is another cost reducer.

Third, rather than constantly rewriting and reprinting of manuals, digital systems resident in the computer can be upgraded in real time. Retraining of staff is reduced by the software upgrades in the maintenance systems and data upgrades. One can leverage software upgrades and use the computer’s capabilities rather than constant re-training of maintenance staff.

Fourth, parts ownership is local in the current system. There is a very difficult and arduous process to move parts from locale A to locale B as aircraft need parts. A global sustainability approach is inherent in the technology built into parts management in the F-35 program whereby transparency of parts can facilitate system ownership of parts rather than local ownership. This leads to reduce time to replace parts, which is another cost savings.

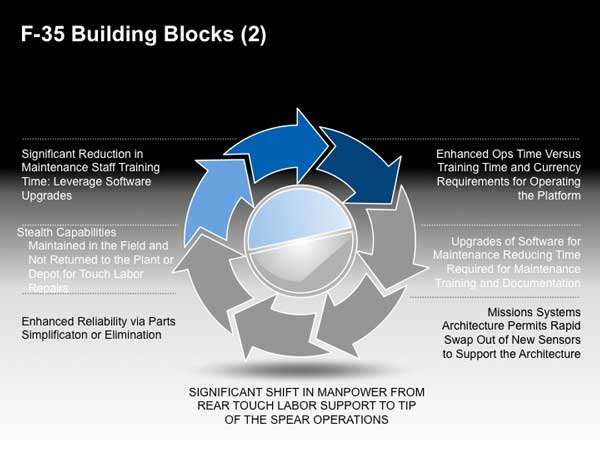

Fifth, the aircraft as a system, it is not simply a platform, provides for significant enhanced ops time versus training time. This means there are cost savings as measured in terms of real time on station for each platform. A classic example is the shift from the Harrier to the F-35B. The Harrier is a difficult plane to fly and requires significant requalification time for its pilots; much of this time is replaced by the ease of flight of the F-35B, which means more time on mission.

Sixth, significant savings come from how the mission systems are to be upgraded. Rather than a piece by piece upgrade and much time spent on aircraft reconfiguration, the missions systems architecture permits rapid swap out of new sensors and systems.

Seventh, the aircraft as a system has eliminated many parts that simply no longer need to be maintained. For example, with regard to hydraulic systems, 80% of the systems have been eliminated, and the use of actuators will facilitate the speed of maintaining what remains.

Eighth, the F-35 is the first field reparable stealth aircraft ever built. The advantages of stealth built into the aircraft will be sustainable in the field, and costly returns to the plant for touch labor repairs will be significantly reduced.

Not only will one gain significant savings from manpower touch labor time on the aircraft, but also the operational tempo will be enhanced. The result will be a significant shift in the use of manpower from rear touch labor support to tip of the spear operations.

All of this is bypassed by the trillion-dollar sustainability assertion. Reality may be harsh, but no need to make it harder by making up analytical numbers and using hypothetical 2065 costs as a basis for 2011 decisions. This reminds one of John Stuart Mill’s wonderful characterizations of Bentham’s philosophy: “Nonsense on Stilts.”