What Weapons that Wait?

By Dr. Scott C. Truver

07/30/2011 – “I have always deemed it unworthy of a chivalrous nation,” Adm. David G. Farragut wrote in 1864, after he “damned the torpedoes” at Mobile Bay. “But, it does not do to give your enemy such a decided superiority over you.”

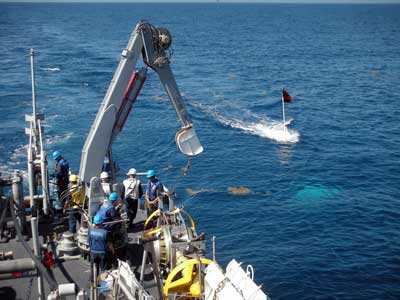

Avenger-class mine countermeasures ship USS Ardent (MCM 12) conducts training with its mine neutralization vehicle and members of Explosive Ordnance Disposal Mobile Unit 1. (Credit: USN Visual Service 07/08/08)

Avenger-class mine countermeasures ship USS Ardent (MCM 12) conducts training with its mine neutralization vehicle and members of Explosive Ordnance Disposal Mobile Unit 1. (Credit: USN Visual Service 07/08/08)

The 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review called for the Air Force and Navy to develop a new concept for defeating potential adversaries — principally China, Iran and North Korea — that possess sophisticated anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities. In response, the AirSea Battle Concept (ASBC) captured the imagination of former Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates, outgoing Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Gary Roughead, and Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Norton A. Schwartz.

The ASBC is to help guide the development of future capabilities for effective power-projection operations. Surprisingly, this seems to include innovative ideas for using naval mines to defeat adversaries’ naval forces and strategies. While still not formally approved as of mid-2011, several observers noted the ASBC seems to address future naval mining capabilities:

- Offensive mining appears particularly attractive, given its comparatively low cost and the difficulty and time-consuming nature of countermine operations. Mining will generally be effective only in areas close to hostile territory, near the approaches to ports and naval bases, and in chokepoints.

- Significant numbers of smart, mobile mines capable of autonomous movement to programmed locations over extended distances will enable offensive mining.

- Stealthy mine-laying platforms capable of penetrating A2/AD systems are preferred for conducting this mission, primarily submarines and stealthy Navy and Air Force bombers.

These AirSea Battle naval mining initiatives are years, if not decades, away from bearing fruit and depend upon a commitment to design, engineer and acquire modern mines, which is problematic at best. Indeed, there’s great doubt that these ideas will ever see the light of day –– and there’s “history” behind this statement.

From the earliest years of the Republic the U.S. Navy has had a “love-hate” relationship with mines… long known as the “weapons that wait.” During the Civil War, the South was much more innovative in using a variety of “torpedoes” than President Lincoln’s Navy. Despite massive employment of mines during World War I and II, the Navy used mines offensively on only two occasions during the Cold War — the 1972 mining of North Vietnamese ports, which brought the North back to the Paris Peace Talks, and mining the northern Persian Gulf in 1991 to prevent Iraqi naval craft from leaving their bases. The Navy also laid more than 11,000 general-purpose bomb-converted Mk 36 “Destructor” mines fitted with magnetic and acoustic sensors along jungle trails during the Vietnam War, something that was duplicated against Iraqi bridges and runways during Desert Storm.

Until recently, the Navy maintained a large stock of mines, including the Destructors, the Mk 67 submarine-launched mobile mine (SLMM), and the Mk 60 CAPTOR (enCAPsulated TORpedo) anti-submarine mine. But with the end of the Cold War, the Navy’s mine capabilities have atrophied.

Today the United States lacks modern mines, and the U.S. stockpile is significantly smaller than North Korea’s estimated 50,000 mines, while the Chinese Navy might have on the order of 100,000, and Russia has been estimated to have 250,000.

The CAPTORs are gone, and only the obsolescent SLMMs and three “Quickstrike” mine variants, which have limited effectiveness in deeper waters against surface targets, are in the Navy’s inventory. But, the SLMMs will be phased out in 2012. At that point, the Navy will have no mines capable of being launched from submarines.

Worryingly, should the Navy actually have to deploy its weapons, there are only a few trained mine specialists on staff. In mid-2011 there were only two minefield planners in the U.S. Navy—a retired USCG captain and a USN Limited Duty/Surface Ordnance Officer assigned to the Naval Mine and Antisubmarine Warfare Command in San Diego—in addition to a handful of enlisted Minemen (none having formal training).

The “workhorses” of the Navy’s mining capabilities are the Quickstrike weapons –– 500-pound (Mk 62) and 1,000-pound (Mk 63) bomb-conversions that are fitted with multiple-influence target detection devices (TDDs) plus the 2,000-pound, “thin-wall” Mark 65 dedicated Quickstrike mine. (The Mk 62/63 mines replaced the Mk 36 Destructors.) All are bottom mines and are deployed from tactical and strategic aircraft.

There is no surface mine-laying capability, although the U.S. Navy might investigate rolling Quickstrike mines off virtually any available ships and craft — something Libya, using Russian/East German “export” mines, did from a ferryboat in the Red Sea during the summer of 1984 — but that doesn’t seem to support ASBC stealthy mine-laying ideas.

Once the SLMMs are phased out, the nation’s sole mine-laying capabilities will reside in naval aviation and the Air Force. The Navy’s P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft and F/A-18 Hornet/Super Hornet can drop Quickstrike mines, but the P-3Cs start leaving service in 2013. They will be replaced by the P-8 Poseidon Multi-Mission Maritime Aircraft, which also will have a modest mining capability, but the ability to do so in meaningful numbers is years away.

The Air Force’s B-52H Stratofortress, B-1B Lancer and B-2A Spirit strategic bombers compose the nation’s only high-volume mining capability. The seemingly ageless (expected to remain in operation through 2040, the first B-52H entered service in 1961) 77 active B-52s each can carry about 45 Mk 62 Quickstrike mines, 18 Mk 63 mines, or 28 Mk 65 mines; the 66 B-1s can carry 84 Mk 62, 24 Mk 62, or eight Mk 65 mines; and the 20 B-2s carry eight Mk 62s. The B-52s and B-1s — but not the stealthy B-2s — train and practice this mission.

However, in wartime, high-volume mining will be only one of several missions demanded of Air Force bombers and, if the minefields are at great distances, their supporting fleet of aerial tankers.

And, aircraft are increasingly at risk from sophisticated integrated air defense systems, as explained in the 2011 USAF Strategic Environmental Assessment.

There were a few, half-hearted post-Cold War efforts to develop new mines: An improved submarine-launched mobile mine based on the Mk 48 torpedo was initiated, but died in 2002; the U.S. Navy-U.K. Royal Navy joint concept for a Littoral Sea Mine was pursued, then dropped; and there was the “2010 Mine” to complement the Quickstrike mines. That program was to provide the fleet with a modern air-dropped mine by 2010. But that, too, was canceled, as was another offensive “networked” mine concept, the Sea Predator 2020 Mine. The denouement is that there is no robust U.S. technological/industrial base in this field.

Some observers have suggested adapting a foreign mine to Navy service. A good idea as several allied navies have modern mine development programs. The U.S. Navy has had some success with foreign weapons and systems, among them the Mk 92 fire control system, the OTO Melara 76-mm guns, the AV-8 Harrier series aircraft, Martin Baker ejection seats, etc.

Suggestions that the Navy acquire modern foreign mines, however, have been met with “not invented here” indifference. As early as 2005 the Secretary of the Navy’s Research Advisory Committee (NRAC) examined the issue and concluded, “The U.S. Navy should consider employing mines in offensive operations, to create barriers to deny areas of interest/operations to hostile submarines, UUVs, and SDVs. The current U.S. mine capability is limited and rapidly dying. It is unlikely that the planned 2020 Mine will be developed on time, at cost, and with the capabilities originally expected. Accordingly, the Panel recommends the use of existing and in-development foreign-built mines that could be fitted with advanced sensors to meet the use described above.”

Cassandras note that foreign-made mines could be difficult to integrate because of weapon safety, delivery vehicle interface, delivery methods, and other technical-operational concerns. Information assurance issues with software-driven technologies are huge, generally, and the Navy would have to ensure there are no embedded “Trojan Horse” or viral codes in the foreign mines. That said, as this was written the Navy was considering a “drill-down” study to get to the “ground truth” about acquiring and employing foreign mines. This nascent interest has not yet translated into funding, and given increasing pressures on Department of Defense and Navy budgets, the situation could likely become “business as usual” with interminable delays in the effort.

Today, there is no U.S. Navy mine program, other than the Quickstrike TDDs. The inability to invest in an advanced new mine looks to be held hostage to resource competition. The Navy’s mine warfare resource sponsor has a difficult challenge: balancing mines/mining with mine countermeasures (MCM), while having to fund legacy and future MCM systems as new systems are being brought on line, with no growth in total funding. Indeed, challenges with the mine warfare module for the littoral combat ships (LCS) recently dictated a redesign of that “mission package,” including additional costs and delays in the future MCM program.

That underscores the fiscal truth of U.S. Navy mine warfare: mines and mine countermeasures — from the labs and industry, and from the Pentagon to deployed forces — usually accounts for less than 1 percent of the Navy’s annual budget.

Nevertheless, several senior Navy officials, including the Chief of Naval Operations and the Commanders, U.S. Third and Fifth Fleets, are warming to the idea of “offensive” mine warfare. Without mines the U.S. Navy essentially gives adversaries a “free pass.” In the fall of 2010, Captain John Hardison, then-deputy program manager of the Navy’s Mine Warfare Programs Office (PMS-495), identified remote control and improved targeting for “offensive mining” as among his “top items of interest.” He essentially echoed Admiral John C. Harvey, Jr., Commander Fleet Forces Command, who earlier said the Navy needs to avoid losing its naval mining capabilities, although the Admiral acknowledged that funding offensive mine research and development is not at the top of his list of priorities.

But specific efforts that could lead to a realistic offensive mining capability are difficult to identify. A new target detection device, the Mk 71 TDD for the Mk 65 Quickstrike has been developed and fielded. The Mk 71 program dates to the early 1990s, with acquisition beginning in fiscal year 2005, but has been delayed by low-level funding, changing priorities, and a “tech-refresh” to make it more producible. The development of a new Mk 75 fuse for other bomb-conversions has also taken longer than anticipated, but should available in a few years. As an example of the fragility of the U.S. mine industrial base, the sole company that has provided a critical component of the TDD has ceased production, spurring the Navy to look for alternative sources—including foreign.

The Quickstrike mines—available and planned—pale in comparison with advanced mine technologies. Captain Mark Rios, Resource Sponsor for Mine Warfare (N852) in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, said that the Navy has the ability to lay indiscriminate mines, but could create mines that would more effectively target enemy ships and could be turned off by remote control after a conflict ends. “I think we want there to be a discussion about how we can use mines,” Rios noted at the 2010 Expeditionary Warfare Conference. “Clearly some of our adversaries or potential adversaries have submarines, have patrol craft that are very nimble and fast. Early on in the conflict, mining their harbors or their approaches to come in and out of port would reduce the number of ships and submarines that could come out to attack us and this reduces the threat.” He has also spoken of “glide mines” with global positioning system targeting, which can be launched from tactical aircraft outside the range of adversary anti-aircraft weapons, and mine-laying unmanned undersea vehicle “trucks” that can be deployed from the Navy’s special-forces-configured cruise missile submarines (SSGNs).

Captain Rios is an optimist. The Sea Predator or 2020 Mine concept called for a remote-controlled, mobile mine that would take advantage of the basic mine characteristics––high-lethality, long-endurance, man-out-of-the-loop, strong psychological impact, and force-multiplying features that free manned platforms for other duties. Sea Predator was also to have autonomous mobility and remote control. It was envisioned to be both submarine- and surface-ship deployable, with the LCS identified as a candidate platform. But, that seems to have dropped out of favor, now.

Thus, while the technologies for improving mines are mature, the Navy’s will to develop, acquire and deploy them remains uncertain—at best. But increasingly, as smaller navies obtain advanced coastal and midget submarines and swimmer delivery vehicles, the potential role of offensive mines increases.

In light of the reality lurking behind the rhetoric of the AirSea Battle naval mining concepts, then, it looks like our A2/AD adversaries will continue to enjoy a “decided superiority” over us.

Scott Truver is director, National Security Programs, at Gryphon Technologies LC. He has supported the U.S. Navy mine warfare community since 1979 and is the co-author of the Naval Institute Press book, Weapons that Wait: Mine Warfare in the U.S. Navy (1991 update), and numerous mine warfare strategy, policy, programmatic and operational studies, reports and articles. He thanks Norman Polmar and several Navy uniformed and civilian mine experts for their insight that helped shaped this commentary. Earlier versions of this essay were published in the June 2011 issues of Seapower magazine and the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings.