Second line of Defense asked Col. Mike Osajda USMCR (ret) to discuss his experiences as an Amtrac Platoon Commander during the Vietnam War. He begins his narrative by pointing out that his tactical doctrine was defined by “Appendix I to Naval Warfare Publication 22.3 Ship to Shore Movement. This was the tactical doctrine at the time.

(The next iteration of this doctrine was published in 1998 and was published after the last big amphibious exercise and can be found here

http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/usmc/fmfm/1-8/fmfm1-8.pdf

The last big exercise is described here

http://www.sldforum.com/2012/03/the-missing-exercise/)

Col Osajda was a 1968 Georgetown University Graduate, who after being a “Trac” Officer went to Northwestern University Law School and successfully completed his Marine career as a member of the JAG Corps.

In Vietnam, a lot of Marines preferred to ride on top of our Amtracs–it was called a flaming coffin for a reason.

But as Col Osajda points out at sea or on land it was what the Marines had available and in the great USMC tradition they did what they had to do!

Also before beginning his narrative he points out given the multiple deployments that Marine combat units have had in what are essentially land campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, it may be that Marine units have not been able to practice the doctrine set forth in NWP 22.

Bold Alligator 2012 obviously is picking up strands of history, moving them forward and shaping templates for future operations. Picking ups the traditions and doctrine from 1970 which now look more like a WWII legacy assault than the revolutionary capabilities being developed as training, tactics and technology continue to go forward to implement a new approach to maneuver warfare from the sea.

“There was a time that we did,”

Lt Mike Osajda’s experience:

As a young Amtrac platoon leader in the early ‘70’s I made numerous amphibious landings using the LVTP 5 series of amphibian tractors.

I landed with LVTP 5s, LVTC 1s and even LVTE 1s (the mine clearance version), in both the Third Amphibian Tractor Battalion and the First Amphibian Tractor Battalion.

In 1970, USS Denver LPD 9 was working up for a West Pac deployment as part of an Amphibious Ready Group. At that time there was always at least one ARG in West Pac. At times there were two; ARG Alpha and ARG Bravo.

An ARG usually consisted of an LPH, LPD, LSD and LST, aboard which was embarked a MAU. (It was called a Marine Amphibious Unit at the time because “Expeditionary” sounded too imperialistic and warlike.)

The MAU usually came from the 3d Marine Division in Okinawa. The infantry battalion would either come from 4th Marines in Camp Hansen or 9th Marines in Camp Schwab.

Denver was performing amphib retraining off the coast of California as part of the redeployment work up. I was a platoon leader in H&S Company 3d Tracs. I was tasked with supporting this training by embarking aboard Denver and working through Denver’s training cycle.

That meant numerous landings; at least 2 , sometimes 3, a day. For a young Lieutenant, those training opportunities were like manna from heaven. Even though the Marines were withdrawing from Vietnam, the combat zone, properly, still received the lion’s share of the operational budget.

There was not a lot of spare money for training for stateside units. And we rarely got a ship from which to operate.

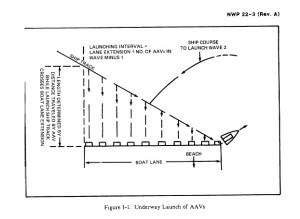

One can occasionally launch a platoon or section from the beach, go out beyond the surf line and simulate a landing, but the value of that exercise is limited. To actually launch over a stern gate, form up, doing the flanking movement, follow the wave control guide boats, hit the beach, splash, recover over the stern gate, respot on your dunnage and tie down on upper vehicle stowage was invaluable.

I was very lucky to have been chosen to make numerous landings that week.

As an aside, I had another pleasant surprise. Because Denver was only concerned about the launch and recovery of amtracs there were no other Marine units involved in this training.

Accordingly, as a Second Lieutenant, I was the CO of troops. I was told by the Navy that I rated the CO of troops quarters; a 2 room suite with a full size bed and an office. Normally, a Col or Lt. Col would occupy those quarters. Not bad for a Brown Bar. I decided I liked working with the Navy.

Our skipper was a professional officer who wanted to get the most of this training opportunity. He called me up to the ward room one day for an interview in the presence of the XO, Ship’s First Lt (who ran the well deck) and some of his other officers. He explained that he wanted to simulate an amphibious raid at night. This was a number of years before the SOC component was added to what a MAU (or MEU) could do. He explained that in a night raid on a potentially hostile beach it was important to keep his ship as elusive as possible.

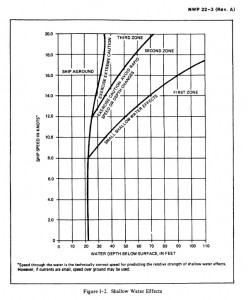

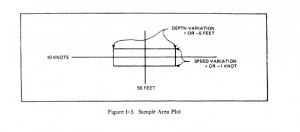

Doctrine stated that the speed of an underway launch would help.

He proposed 20 knots. He would add the element of maneuvering. He intended to zig zag his ship during the approach to the LOD. At the appropriate time, he would cease his maneuvering, run parallel to the LOD and signal the well deck to commence a launch. The First Lt. would pass the signal to my platoon. We would launch. When the last vehicle splashed, he would commence evasive maneuvering again and proceed out of shore battery range. He then stated that if I was able to splash two vehicles at a time, my platoon could clear his boat quicker, thereby offering less exposure to his more expensive asset.

He wanted to know whether I thought my platoon could effect the maneuver and if I was willing to participate in the exercise. With the foolishness of youth, a lack of understanding of the dangers of exiting a 17,000 ton vessel over a stern gate at night at 20 knots and supreme confidence in my Marines, I immediately agreed.

My recollection is that I was configured as if I was being deployed. That meant that I had 11 vehicles, a reinforced platoon, not the 10 vehicle platoon. I was reinforced by an LVTC 1, a command vehicle, configured with extra radios to be able to control a regimental sized unit. Practically, that meant that I would splash two waves of 5 and 6 tractors.

We did not do a dry run in the day time.

At the appointed hour the ship began its maneuvering to the LOD. I was in the well deck so I cannot describe anything but the pitching and swaying of a large vessel doing violent course changes to avoid giving a target to shore batteries. Our vehicles were staged in two parallel lines spotted on the well deck facing the stern. We were going to be launched with the ship going up the coast toward San Clemente or Los Angeles.

That meant that the shore was starboard of the ship and to our port. We were on the well deck rather than upper vehicle stowage because the well deck would flood no more than 3 feet. Unlike recovery operations when we float into the well, ground well inside the ship, perform a neutral steer and back up to our parking position in upper vehicle stowage, we would launch before we would just drop off the stern. The theory was that with the speed of the ship in the opposite direction we would not even go under the surface. Unlike a launch from an LST.

The red lights were turned on and the stern gate was lowered to a little below parallel. The well deck was flooded until there was about 3 feet over the stern. The ship still canted left and right while the evasive maneuvering went on. The view out of the well was very dark. We cranked up our Continental V -12 mogas powered engines.

We knew that we would be able to see the exhaust fumes from the “dog houses” on the rear of the vehicles. That would at least give us some visual references. My Platoon sergeant and I would be the wave commanders on the flanks. We performed radio checks so that we would be able to control our waves by telling each wave when to perform a left flank and then to tell each vehicle to stay on line.

We were ready.

All eyes were on the Ship’s First Lt. who was on a gallery on the starboard side of the well deck. The ship came on to a straight course. The pitching stopped. The Ship’s First Lt gave us the launch signal. Two by two the tractors gunned their engines and went across the stern gate. There was not an equal internal of time between launches. The first two vehicles we so close to the stern gate that they had little forward speed when they hit the water. The “plopped” into the water at 3 or 4 miles an hour. Because the ship was moving at 20 knots, an interval appeared, so the next vehicles were launched. They had a little more forward speed, so it took less time for the proper interval to appear.

By the time the last vehicle launched (mine), we were probably going 15 mph over the stern. By that time we just slid in the water. I don’t even recall buttoning up. Hatches open; no water in the hatches. Looking back, I guess we should have been happy that no vehicles were sucked into the wake of the ship. But the innocence of youth and great execution by the Navy-Marine Corps team made the launch operation flawless. My recollection tells me that we launched 11 tractors in 2 parallel waves flawlessly in 48 seconds. The ship was able to recommence evasive maneuvers and clear the LOD.

For control purposes, the Gunny was the last vehicle out of the first wave of 5 tractors, and I was the last vehicle out of the second wave of 6 tractors. We were able to see the exhaust of each vehicle to determine proper spacing and alignment.

We maneuvered each vehicle so that the alignment was correct and then did a simultaneous left flanking movement. Once that occurred, I slowed down my wave to get the appropriate space between waves. Then the Gunny and I guided each of our waves toward the beach. I don’t recall if there was a wave control guide boat provided by the Navy or if both the Gunny and I were given the guide frequency from the Primary Control Ship. In either case we proceeded to the correct beach and made safe landings with two waves of tractors.

We then recovered the vehicles at night, which a another great training exercise. It was non tactical. The ship was lit up. But still, splashing in the pitch dark and proceeding out to a ship and recovering was a great training experience.

That was the highlight of my brief deployment aboard Denver. I have served aboard a number of amphibious ships and had valuable experiences aboard them all.

Power projection is a task that the Navy Marine Corps team performs well. I hope that we can continue to do so in a professional manner.

Featured photo: Credit

http://lalettredelaphotographie.com/archives/by_date/2012-02-23/5632/life-john-olson-hue