2012-07-12 by Scott C. Truver, Director, TeamBlue, Gryphon Technologies LC

As tensions between the United States and Iran increased in early 2012, with threats from Teheran to close the Arabian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz––exacerbating concerns in jittery world petroleum markets––countered by increasingly draconian U.S. and UN sanctions, a U.S. Navy admiral declared, “If Iran mines the Arabian Gulf, it’ll be an act of war.”

Well…maybe.

As it turns out, there are international guidelines for naval mining and, if followed, enable navies to deploy their “weapons that wait” in peacetime as well as “armed conflict.”

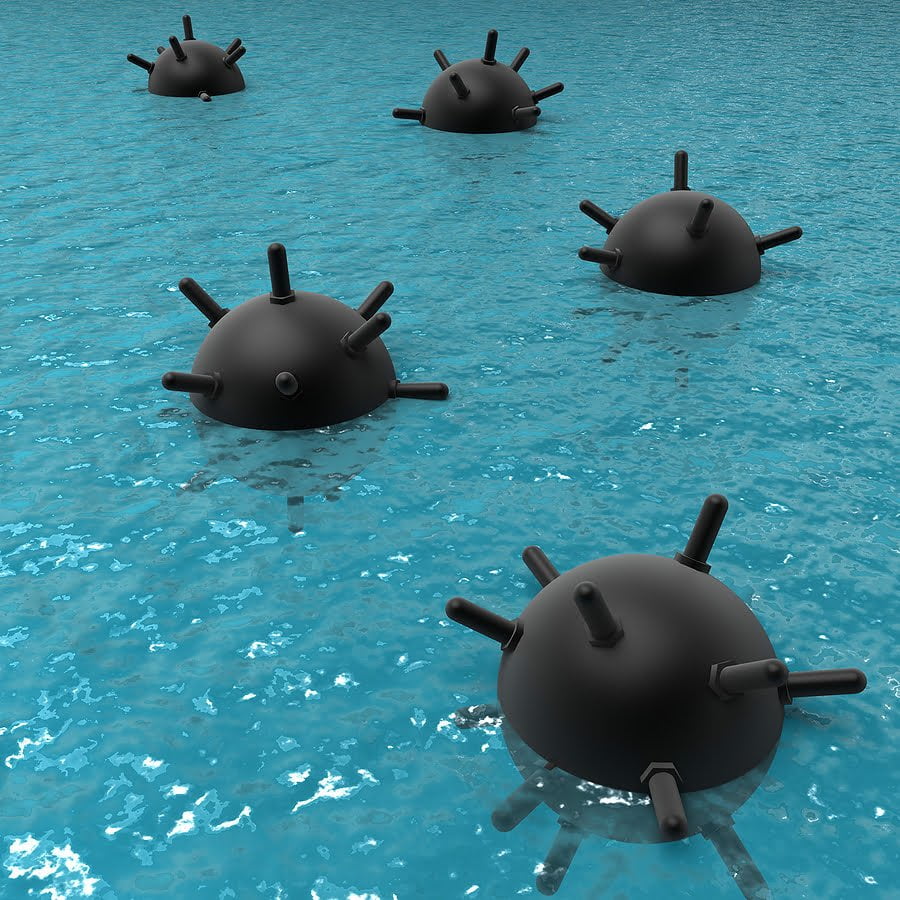

For example, the Hague Convention VIII of 1907 focuses on “The Laying of Automatic Submarine Contact Mines” (Section VII) during times of war.[1] “Automatic” mines are those weapons not under the direct control of the miner, whether anchored to the sea bottom or not. In 1907, this meant primarily contact weapons (still in many navies’ inventories in 2012), but the rules would also apply to “influence” weapons that fire on the magnetic, acoustic, pressure, electric-potential and seismic “signatures” of a target surface ship or submarine. In that regard, Articles 1-2 state, “It is forbidden” to lay:

- To lay unanchored (i.e., drifting) automatic contact mines, except when they are so constructed as to become harmless one hour at most after the person who laid them ceases to control them

- To lay anchored automatic contact mines which do not become harmless as soon as they have broken loose from their moorings

- To lay automatic contact mines, whether anchored or not, off the coast and ports of the enemy, with the sole object of intercepting commercial shipping.

Article 3 stipulates that when anchored automatic contact mines are employed, every possible precaution must be taken for the security of peaceful (a broader category than just commercial) shipping. Belligerents must “do their utmost’ to render these mines harmless within a limited time (not just an hour). Furthermore, should these mines cease to be under the miner’s surveillance, the mining countries must notify ship owners and governments through diplomatic channels about the mine danger zones “as soon as military exigencies permit.”

“Neutral Powers” that lay automatic contact mines off their coasts must follow the same rules as are imposed on belligerents. (Article 4.) The neutral state must inform ship owners, by a notice issued in advance, where automatic contact mines have been laid, and this notice must be communicated at once to the governments through diplomatic channels.

At the close of the war, the “Contracting Powers” (i.e., states party to the 1907 convention) must do their utmost to remove the mines that they have laid, with each government responsible for removing its own mines. (Article 5.) With regard to anchored automatic contact mines laid by one of the belligerents off the coast of the other, their positions must be notified to the other party by the Power that laid them, and each Power must proceed with the least possible delay to remove the mines in its own waters. For example, after the U.S. Navy mined Haiphong harbor and other North Vietnamese waterways in July 1972 and the Paris Peace Talks resumed in January 1973, U.S. mine countermeasures (MCM) forces were responsible for clearing all mined areas––Operation End Sweep––later that year. As it turned out, most of the mines had already been rendered safe through self-sterilization.

For the U.S. Navy today, the Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations[2] outlines the rules of the road that must be followed, whether during peace, crisis or war:

9.2.2 Peacetime Mining

Consistent with the safety of its own citizenry, a nation may emplace both armed and controlled mines in its own internal waters at any time with or without notification. A nation may also mine its own archipelagic waters and territorial sea during peacetime when deemed necessary for national security purposes. If armed mines are emplaced in archipelagic waters or the territorial sea, appropriate international notification of the existence and location of such mines is required. Because the right of innocent passage can be suspended only temporarily, armed mines must be removed or rendered harmless as soon as the security threat that prompted their emplacement has terminated. Armed mines may not be emplaced in international straits or archipelagic sea lanes during peacetime. Emplacement of controlled mines in a nation’s own archipelagic waters or territorial sea is not subject to such notification or removal requirements.

Naval mines may not be emplaced in internal waters, territorial seas, or archipelagic waters of another nation in peacetime without that nation’s consent. Controlled mines may, however, be emplaced in international waters (i.e., beyond the territorial sea) if they do not unreasonably interfere with other lawful uses of the oceans. The determination of what constitutes an “unreasonable interference” involves a balancing of a number of factors, including the rationale for their emplacement (i.e., the self-defense requirements of the emplacing nation), the extent of the area to be mined, the hazard (if any) to other lawful ocean uses, and the duration of their emplacement. Because controlled mines do not constitute a hazard to navigation, international notice of their emplacement is not required.

Armed mines may not be emplaced in international waters prior to the outbreak of armed conflict, except under the most demanding requirements of individual or collective self-defense. Should armed mines be emplaced in international waters under such circumstances, prior notification of their location must be provided. A nation emplacing armed mines in international waters during peacetime must maintain an on-scene presence in the area sufficient to ensure that appropriate warning is provided to ships approaching the danger area. All armed mines must be expeditiously removed or rendered harmless when the imminent danger that prompted their emplacement has passed.

9.2.3 Mining during Armed Conflict

Naval mines may be lawfully employed by parties to an armed conflict subject to the following restrictions:

1. International notification of the location of emplaced mines must be made as soon as military exigencies permit.

2. Mines may not be emplaced by belligerents in neutral waters.

3. Anchored mines must become harmless as soon as they have broken their moorings.

4. Unanchored mines not otherwise affixed or imbedded in the bottom must become harmless within an hour after loss of control over them.

5. The location of minefields must be carefully recorded to ensure accurate notification and to facilitate subsequent removal and/or deactivation.

6. Naval mines may be employed to channelize neutral shipping, but not in a manner to deny transit passage of international straits or archipelagic sea lanes passage of archipelagic waters by such shipping.

7. Naval mines may not be emplaced off the coasts and ports of the enemy with the sole objective of intercepting commercial shipping, but may otherwise be employed in the strategic blockade of enemy ports, coasts, and waterways.

8. Mining of areas of indefinite extent in international waters is prohibited. Reasonably limited barred areas may be established by naval mines, provided neutral shipping retains an alternate route around or through such an area with reasonable assurance of safety.

Although something of a thorn in the side of naval planners today, the rules have potential significant impact on future U.S. Navy and Air Force offensive mining concepts that apparently are part-and-parcel of the AirSea Battle Concept (ASBC).

Observers have noted the ASCB identifies several important naval mining capabilities:

- Offensive mining appears particularly attractive, given its comparatively low cost and the difficulty and time-consuming nature of countermine operations. Mining will generally be effective in areas close to hostile territory, near the approaches to ports and naval bases, and in chokepoints. Defensive mining can also contribute to protection of our forward bases, forces, and operations.

- Advanced smart, mobile and controllable mines will reduce required quantities and add tactical flexibility to U.S. operations.

- Advanced smart, mobile and controllable mines and armed unmanned undersea vehicles will lead the effort in anti-submarine warfare campaigns.

- Significant numbers of smart, mobile and controllable mines capable of autonomous movement to programmed locations over extended distances will enable offensive mining and be particularly effective in attriting adversary submarines and/or blocking them from access to their bases.

- Stealthy mine-laying platforms capable of penetrating anti-access/area-denial systems are preferred for conducting this mission, primarily submarines and stealthy Navy and Air Force bombers.

Perhaps honored more in their breach than observance (as evidenced by Albania’s mining of the Corfu Channel in 1946 and Iran and Iraq’s indiscriminate use of mines during the 1980s “Tanker War”), the laws of naval mining are nonetheless clear.

If the rules were followed, in peacetime, crisis and armed conflict, Iran’s (and any other country’s) use of naval mines––particularly in a self-defense role––would not, per se, be an “act of war.”

But, that’s a big “if.”

And, little wonder that the U.S. Navy has buttressed its MCM forces in the Arabian Gulf. Just in case.

[1] Yale Law School, The Avalon Project (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/hague08).

[2] Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. Navy, NWP 1-14M, July 2007), pp. 9-2 – 9-3