2012-08-26 by Robbin Laird

The Pacific is a big place.

It often either not understood and not reflected upon the scope and nature of the Pacific region. This is not the Mediterranean; this is not the Indian Ocean; this is not even the Atlantic.

As Ed Timperlake put it clearly:

The Pacific is nothing like the name –“Pacificum” or peaceful in Latin. It is a violent and expansive Ocean. Rounding the tip of South America. Ferdinand Magellan, in perhaps one of the more significant “name branding” mistakes in history pronounced the body of water he saw as peaceful.

The Size of the Pacific Ocean is Massive; it covers more than one-third of the earth’s surface, which is approximately 165 million square kilometers (about 65 million square miles). It extends about 15,000 kilometers (9,600 miles)….

A famous World War Pacific Typhoon makes that startling point. Historians have debated the number of USN Ships sunk by Japanese Kamikaze attacks during all of WW II in the Pacific. Their counts vary from a low of 34 to a high of 47.

Compare that Kamikaze fight against a reactive enemy over a almost a four year war with a US Task Force caught in a Pacific Typhoon in one 24 hour period.

In the Pacific Typhoon of December 18, 1944 three Destroyers capsized; the USS Spence, USS Hull, USS Monaghan, with the loss of most of their crew–over 700 hundred sailors perished. Additionally, 146 aircraft on Fleet Carriers were struck from the rolls because of damage.

I started by looking at the challenge of sustaining forward presence in an ocean of such size, scope and violence. Now I want to turn to the question of defending the littorals – the American littorals.

In the next piece I will look at Alaska and the Arctic, with a focus on Alaska as a key strategic asset for U.S. Pacific operations.

To give one a sense of how to look at the Pacific challenges facing the United States, which has been a Pacific power at least from the time of “owning” the Philippines at the end of the 19th century, we need to turn the globe.

From an American perspective, the Pacific begins in the Alaska and Arctic and arcs down through Australia. The 50th state – Hawaii – is in the middle of this perspective.

From Seattle to San Diego, the U.S. has many key cities in the Pacific Basin. And the economic impact of the Asian relationship is evident everywhere in the region. The impact of maritime trade is central. And these cities and their ports are part of the conveyer belt of goods transferred from Asia to the United States and beyond.

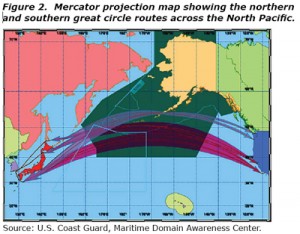

Also underscored are the trade routes for the conveyer belt, which follow the Great Circle Route from the Asian ports south of Alaska and then down the West Coast of the United States.

The defense of the littorals is a major task and challenge. It encompasses looking at the Pacific east of Hawaii and examining the scope and nature of littoral operations. Maritime trade and commerce is a big part of the picture, but again one needs to recognize that such trade and commerce largely comes via the Great Circle Route from Asia then South of Alaska and then to the West Coast ports of the United States.

Defense of the littorals requires working safety and security of maritime trade and commerce, managing environmental threats and the management of the fisheries and building a sound and safe security system end-to-end from Asia to the United States. This means that the Ports must be safe from the intrusion of terrorist threats or asymmetric actions by potential adversaries in the Asian region.

Safety, security and defense of the littorals are part of the same package to ensure that the foundation for a sound Pacific strategy is laid. U.S. ships and aircraft operating out of the United States need to be free of threats – the Pacific ports are especially challenged and ballistic missile threats originating from the Pacific can threaten even CONUS based aircraft.

The USCG plays a special joint agency role in providing for littoral defense of the United States, and as such is a Title X or defense agency in the United States, not simply a homeland security agency.

The USCG is a key agency in managing maritime safety and security for the American littorals in the Pacific. And such management tasks are at the same time baseline defense tasks.

If you can not protect the entry points into the United States, the nation will clearly not have an effective foundation for a defense and security strategy in the Pacific.

And highlighting the USCG role in the Pacific, in turn, underscores the key synergy between security and defense tasks and operations in shaping a 21st century approach to Pacific strategy. Threats are embedded in the normal operations of the maritime trade system; managing these threats is a foundation element for the defense of the United States in the Pacific.

As Vice Admiral Manson Brown, then the US Coast Guard Pacific Commander and now Deputy Commandant for Mission Support, underscored in an interview last year:

Many people believe that we need to be a coastal coast guard, focused on the ports, waterways, and coastal environment.

But the reality is that because our national interests extend well beyond our shore, whether it’s our vessels, or our mariners, or our possessions and our territories, we need to have presence well beyond our shores to influence good outcomes.

As the Pacific Area Commander, I’m also the USCG Pacific Fleet Commander. That’s a powerful synergy. I’m responsible for the close-in game, and I’m responsible for the away game. Now the away game has some tangible authorities and capabilities, such as fisheries enforcement and search and rescue presence.

https://www.sldinfo.com/the-uscg-in-the-pacific/

At the heart of a strategic rethink in building a U.S. Pacific maritime security strategy is coming to terms with the differences between the security and military domains. The security domain is based on multiple-sum actions; military activity is by its very nature rooted in unilateral action. If one starts with the military side of the equation and then defines the characteristics of a maritime security equation the formula is skewed towards unilateral action against multiple-sum activity.

But there is another aspect of change as well. Increasingly, the United States is rethinking its overall defense policy. A shift is underway toward preparing its forces for global operations for conventional engagement in flexible conditions.

Conventional engagement is built on a sliding scale from insertion of forces to achieve political effect to the use of high intensity sledgehammer capabilities. Policymakers and specialists alike increasingly question the utility of high-tech, high intensity warfare capabilities for the majority of conventional engagement missions.

The classic look at the relationship between the USCG and the USN is rooted in a sliding scale on level of violence. This classic look needs to be replaced by a new look, which emphasizes the intersection between security operations and conventional engagement, with high intensity capabilities as an escalatory tool.

The new look would emphasize the interconnection between the collaborative efforts in the security domain with those in the conventional engagement domain. In fact, the engagement necessary on the multi-national level to achieve maritime security is a foundational element for shaping multi-national coalitions to pursue military actions, when necessary.

To protect the littorals of the United States is a foundational element for Pacific defense, and allows the U.S. to focus on multiple sum outcomes where possible to enhance defense and security, but at the same time lays a solid foundation for moving deeper into the Pacific for military or extended security operations as necessary.

A reflection of such an approach is the North Pacific forum. Again one must remember the central place, which the Great Circle Route plays in trans-Pacific shipping and the immensity of the Pacific. Given these conditions, the USCG has participated in a collaborative security effort in the North Pacific designed to enhance littoral protection of the United States.

Among key participants in this Forum are the Canadians, Russians, the Japanese, the South Koreans and the Chinese.

As long time participant in many sessions of the North Pacific forum, Admiral Day has underscored:

The North Pacific CG Forum has conducted numerous exercises and several joint operations and each of the members have contributed assets or personnel; Japan and Korea, because of the coastal nature of their vessels, have generally provided air (Japan) or personnel (shipriders) for operations being conducted on the high seas.

We created what was called a combined operations group. This workgroup had representatives from each of the countries and formulated the processes and procedures so that we could effectively operate together for a wide variety of scenarios.

But for the United States to play a more effective role in defending its own littorals and to be more effective in the kind of multi-national collaboration which building Pacific security and providing a solid foundation for littoral defense, a key element are presence assets.

As Vice Admiral Manson Brown put it simply:

And it’s presence, in a competitive sense, because if we are not there, someone else will be there, whether it’s the illegal fishers or whether it’s Chinese influence in the region. We need to be very concerned about the balance of power in the neighborhood.

If you take a look at some of the other players that are operating in the neighborhood there is clearly an active power game going on.

For the evolution of U.S. strategy in the Pacific, littoral security and defense is a crucial element. And to perform these tasks, a core set of assets revolves around USCG cutters.

The inability to fund the National Security Cutters and the putting in limbo of the smaller cutters, the so-called OPCs, or Offshore Patrol Cutters really underscores: without effective littoral presence (for U.S. shores) how does one do security and defense in the Pacific?

If the USCG’s role in Title X or in defense to put it simply is not highlighted and prioritized we will be left with at best a coastal coast guard, not one capable of reaching out deeper in the Pacific to provide for real littoral security and defense.

The size and immensity of the Pacific means you operate with what you have; you do not have shore infrastructure easily at hand to support a ship. Ships need to be big enough to have onboard provisions and fuel, as well as aviation assets to operate over time and distance.

Again quoting Vice Admiral Manson Brown:

And the thing you have to realize in the Pacific, you don’t have the infrastructure that you do in the Atlantic.

So in terms of pier space, fuel, engineering support, food and other logistics, you have to take it with you.

In short, providing for littoral defense and security on the shores of the United States will need see a reaffirmation of the Title X role of the USCG and ending the logjam of funding support for the cutter fleet and the aviation assets which enable that fleet to have range and reach.

An earlier version of this piece appeared in my series on the pivot to the Pacific on AOL Defense.

For Special Reports which look at the USCG and Pacific Strategy and at the Role of the National Security Cutter see the following:

https://www.sldinfo.com/national-security-cutter-special-report/

https://www.sldinfo.com/the-national-security-cutter-in-rimpac-2012n-rimpac-2012/