2012-09-13 By Richard Weitz

Japan’s relationship with China, burdened by history and intermittent geopolitical disputes, is complex, made ever more so by the PRC’s meteoric rise in recent years.

Coinciding with Japan’s “lost decade,” China enjoyed rapid industrial growth during the 1990s and is becoming the world’s second-largest economy according to many measurements.

Japan’s security concerns regarding China include the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and China’s expanding military budget, the status of Taiwan, and access to shipping lanes and natural resources in the East China Sea.

More generally, the Japanese have been perhaps the nation perhaps most uneasy about the growing economic and military power of the PRC.

A few years ago, a Japanese government-sponsored task force described Sino-Japanese ties as the “interweaving of ‘cooperation and co-existence’ with ‘competition and friction,’ a characterization that still holds.”

Chinese leaders view warily Japan’s growing military capabilities, expanding security role in East Asia, and efforts to revise the pacifist clauses in the Japanese constitution. The South China sea is an important flashpoint. Credit Image: Bigstock

Many Japanese continue to see China as replete with tremendous commercial opportunities. Sino-Japanese trade has surpassed U.S.-Japan trade, making China Japan’s top trading partner even excluding goods and service exchanged via Hong Kong. It is also a major destination for Japanese direct investment.

Saddled with guilt for its fifteen-year occupation of China, the Japanese government provided the PRC with more than $23 billion in development assistance from 1979 to 1999—despite Japan’s running a trade deficit with Beijing.

For almost two decades, Japan’s leaders and public alike have expressed alarm at Chinese foreign policy actions.

During the March 1996 crisis over Taiwan, the PRC launched missiles in the island’s vicinity, threatening regional maritime commerce. Some of the missiles landed less than 100 kilometers from Okinawa. A few months later, the sovereignty dispute between China and Japan over the Senkaku-Diaoyutai Islands revived.

Japanese policy makers have also expressed concern about the China’s surging military spending, which has increased by double digits for many years, a level exceeding the country’s average annual economic growth rate. The Japan Defense Agency’s Defense of Japan 2005 identified, for the first time, China’s military modernization as potentially threatening and called on Beijing to make its defense programs more transparent.

On September 27, 2006, the new Director General of the Japanese Defense Agency, Kyuma Fumio, told the media that Chinese military power had become so great that it would be “impossible for Japan to deal with it single-handedly, no matter how much money we spent for our defense buildup.” In Fumio’s assessment, only the U.S.-Japan mutual defense treaty could counter this imbalance.

Sino-Japanese relations improved after Abe became Japan’s prime minister on September 26, 2006. His October 9, 2006 visit to Beijing ended an 18-month freeze on bilateral summits between the heads of the two governments.

Before then, the Chinese government had suspended high-level summits with Japanese leaders outside the context of multilateral gatherings in order to protest Koizumi’s annual visits to the Yasukuni Shrine. The Chinese and other Asian nations perceive Yasukuni, which honors Japan’s 2.5 million war dead, as a symbol of Japanese militarism.

Popular relations between Chinese and Japanese people reached a low point under his tenure when, in August 2004, Chinese fans booed Japan’s national soccer team when it played at the Asia Cup tournament in Chongqing.

In November 2006, China and Japan resumed their working-level defense dialogue, which had been in abeyance since March 2005.

Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao’s April 2007 visit to Japan further advanced the modest détente that has marked Sino-Japanese relations.

Despite the high-profile cultural and business exchanges that characterized the visit, Wen’s warning underscored the underlying tensions that still trouble the relationship between the two governments.

For example, Wen and Abe failed to achieve discernible progress on the Sino-Japanese dispute over the energy resources under the East China Sea.

Even as Wen visited Tokyo, Japanese officials expressed concern about a report that China’s state-controlled CNOOC Ltd. had begun processing oil and natural gas from the Chunxiao/Shirakaba gas fields that are currently disputed by the two countries.

At the summit, the two governments agreed only to continue bilateral discussions and to review a report on how their countries could jointly develop the undersea natural resources. Their present energy cooperation focuses mostly on bilateral conservation and environmental measures.

Furthermore, when Abe visited Europe in January 2007, he urged the EU governments not to lift their embargo of arms exports to China, arguing such a move would adversely affect the security situation in East Asia.

Like other governments, the Japanese criticized China for its failure to notify other countries in advance about its anti-satellite (ASAT) test and then for delaying its subsequent confirmation about the incident. Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Aso complained that China should have given Japan advanced notice.

Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary Yasuhisa Shiozaki warned that Beijing’s lack of openness about the incident could reinforce doubts about China’s peaceful motives. Abe told the Japanese Diet that China’s test might have violated international law since the 1967 UN Outer Space Treaty, which bans weapons of mass destruction in space, requires all countries to avoid contaminating space with debris.

At the April 2007 summit, Chinese and Japanese leaders agreed to create a “hot line” between their defense establishments. They also advanced plans to expand military exchanges, including reciprocal naval ship visits.

In June 2008, a Japanese destroyer docked at a Chinese naval port for the first time since World War II. Another first had occurred the previous month, when the Japanese SDF delivered relief aid to China after the earthquake in China’s Sichuan Province on May 12, 2008.

The planned defense communications link might help prevent the inadvertent escalation of future military incidents, such as when the Japanese detect yet another Chinese submarine in their territorial waters. Neither the hot line nor the exchanges, however, will directly address the more general apprehension in Japan regarding China’s long-term military plans.

In May 2008, Hu Jintao concluded the first state visit by a Chinese president to Japan in almost a decade. President Jiang Zemin traveled to Japan in 1998, but the subsequent deterioration in relations between Beijing and Tokyo severely curtailed high-level meetings.

The summit failed to generate concrete progress on the main differences between the two countries. For example, the two heads of state proved unable to resolve the Sino-Japanese dispute over the East China Sea and its valuable natural gas reserves.

The bilateral negotiations that began in 2004 have neither reconciled their conflicting sovereignty and territorial claims nor established an agreed mechanism for joint exploitation of the energy reserves, which lie within their overlapping maritime economic zones.

Chinese-Japanese energy collaboration remains primarily confined to unobjectionable areas such as cooperative conservation and environmental programs.

In the National Defense Program Guidelines announced in December 2010, the Japanese government expressed concern about the PRC’s military build-up as well as its increasing maritime activities in waters near Japan’s southwest island chain.

Japanese and U.S. officials have adopted hedging policies aimed at responding to a situation in which the PRC’s rising economic, political, and military power becomes a security threat. To Beijing’s annoyance, the Japanese and American foreign and defense ministers participating in the February 2005 SCC session publicly identified for the first time the “peaceful resolution of issues concerning the Taiwan Strait” as a “common strategic objective” in the Asia Pacific region.

When China’s 2002 Defense White Paper expressed disquiet over joint U.S.-Japanese research on BMD, the unstated concern was that the two countries could share BMD technologies with Taiwan, negating Beijing’s strategy of deterring the island’s independence aspirations by threatening missile strikes in response to Taipei’s assertions of greater autonomy.

In addition, Chinese leaders view warily Japan’s growing military capabilities, expanding security role in East Asia, and efforts to revise the pacifist clauses in the Japanese constitution.

In particular, Beijing fears that Tokyo’s expanding military cooperation with the United States could lead to the provision of de facto Japanese assistance to Taiwan in a future cross-straits confrontation. Chinese strategists especially worry that Tokyo and Washington could share missile defense technologies with Taiwan, negating Beijing’s deterrent strategy of threatening missile strikes in response to Taiwanese assertions of greater autonomy.

Over the long term, Chinese security experts fear that Japan could exploit its technological and industrial potential, including the country’s latent nuclear weapons capacity, to become a major military power. The decision of a Japanese parliamentary committee to authorize the government to use Japan’s robust space capabilities for “non-aggressive” military purposes could exacerbate such concerns.

——–

The pull of China, Japan and South Korea into contested dynamics is an important development affecting a 21st century Pacific strategy. Below is more information on the China-South Korea part of the triangle.

THE EAST CHINA SEA DYNAMIC

2012-07-11 The East China Sea has been contested for decades by South Korea, China and Japan, all seeking to tap huge oil, gas and mineral reserves believed be buried under the seabed.

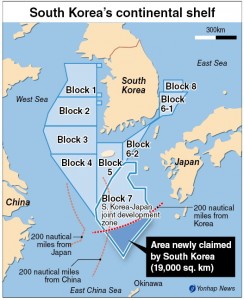

With their extended continental shelves overlapping in the northeastern part of the ocean, the Asian powers are laying formal claims with a U.N. body in charge of sea shelf carve-up.

The three-way jousting recently took a twist. Seoul and Beijing are working on a joint submission to counter Tokyo’s increasingly aggressive push in maritime issues.

The unlikely alliance with China could mark a turnaround for Korea, which has lacked assertiveness against its powerful neighbors.

But experts say defending maritime interests is still an uphill battle for Korea, which is far behind in terms of scientific data, diplomatic prowess and domestic legislation.

South Korea’s Continental Shelf. Credit Image: The Korea Herald

With inland resources depleting at a brisk clip, a surging number of countries have turned to the ocean, which covers more than 70 percent of the planet’s surface.

More than 1.6 trillion barrels of crude, or about 32.5 percent of the world’s reserves, are thought to be buried under the ocean floor, according to Samsung Economic Research Institute.

Driven by their ever-growing thirst for energy, the three Asian powers are excavating seabed minerals at home or abroad, cultivating the latest exploration and extraction technologies and stocking up on related equipment.

“The skyrocketing resources consumption across the region and stiffening competition in the international commodity market have prompted Korea, China and Japan to reinforce strategies to develop wells in their waters. This trend interlocks with the sea shelf boundary issue, generating a conflict factor,” Lee Dal-seok, head of energy policy research at the state-run Korea Energy Economics Institute

“Any potential discord Korea may face while pursuing submarine oilfields originates from intense competition for energy in East Asia,” Lee said.

The East China Sea has become a flashpoint chiefly due to its treasure trove of crude oil and natural gas that came to light after a U.N. survey in 1968. ….

Armed with its growing financial firepower, China is also rushing to access untapped reserves across the globe. Its state-run enterprises such as Sinopec, CNOOC and PetroChina are rapidly biting into a market long occupied by global giants such as Exxon Mobil, BHP Billiton, Chevron and Petrobras.

Beijing has recently developed a manned submersible capable of operating up to 6 kilometers below the surface. It aims to secure more than 15 ultramodern deepwater exploration vehicles by 2020 and mobilize at least three vessels of 4,000 tons or heavier…..

By Shin Hyon-hee (he*****@*****dm.com)

Song Sang-ho contributed to this report. ―

The Korea Herald

To read the complete article see

http://view.koreaherald.com/kh/view.php?ud=20120710001337

For an analytical look at the maritime disputes discussed see Strategic Insights No. 39

https://www.sldinfo.com/products/april-2012-si/