2012-09-02 By Richard Weitz

Since Saddam was ousted in 2003 until recently, two issues have dominated the Iraqi-Syrian relationship.

- Syria’s initial decision to host the remnants of the Iraqi Baath Party who fled Baghdad aroused fear and resentment with the new government in Baghdad.

- Iraqi authorities suspected that Syria was allowing insurgents to move men and supplies across their border into Iraq.

Syria has offered respite for Iraqis fleeing their country since the 1990s under Saddam.

Following the 2003 Anglo-American invasion, and Iraq’s subsequent descent into civil war, the exodus of refugees from Iraq to Syria increased. By 2010, more than a million Iraqis had taken refuge in Syria, straining local resources.

In the event that a massive exodus of Iraqis returns from Syria (in light of the growing civil war and sectarian strife), Iraq is unprepared to support the basic needs of its population.

It was not until 2006 that the two countries restored diplomatic relations and exchanged high-level leadership visits. But bilateral tensions persisted over suspicions that Syria was still aiding Iraqi insurgents.

In 2009, the new Obama administration sought to engage Damascus in an effort to woo Syria away from Iran as well as explore joint efforts to promote stability in Iraq.

But Prime Minister al-Maliki, who despised the Assad regime’s Baathist ideology even while he benefited from taking sanctuary in Syria during the 1990s, accused Syrians of complicity in a series of bombings of government buildings in August 2009, which killed and wounded hundreds of people.

The Iraqi government refused to participate in the planned border security talks between the Syrian authorities and the U.S. Central Command and demanded the extradition of former Iraqi Baathist leaders living in Syria who were suspected of being responsible for the bombings

Analysts saw the bombings as a Syrian effort to embarrass al-Maliki politically (the Syrians favored opposition leader Iyad Allawi at the time) as well as gain leverage with the United States. The Syrian authorities denied any involvement and both governments recalled their ambassadors.

It was only in 2010 that relations between Baghdad and Damascus significantly improved.

At Tehran’s urging, Syria abandoned Allawi and joined Iran in backing the creation of the Shiite-dominated coalition government in Baghdad in which al-Maliki remained prime minister.

In September 2010, al-Maliki sent al-Assad a message urging that the two countries pursue better relations.

Later that month the Iraqi Ambassador returned to Damascus, while al-Maliki went to Syria the following month. During al-Maliki’s visit, the Iraqi oil minister and his counterpart signed a memorandum of understanding on bilateral energy cooperation.

When Syria’s prime minister visited Iraq in January 2011, the two governments agreed to ease cross-border travel restrictions. In February 2011, Iraqi President Jalal Talabani met with al-Assad in Damascus to discuss building a stronger relationship between the two countries.

Iraq and Syria exert significant levers of influence on one another’s behavior.

- Syria provides Iraq access to the Mediterranean while Syrians have important ties with the various Iraqi political actors including tribal shaykhs, representatives of the Sunni parties and religious organizations, as well as leaders of Iraq’s Kurdish factions and, with the help of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, representatives of Iraq’s Shiite community.

- Many currently influential Iraqis lived in exile in Syria during Saddam’s regime, including al-Maliki and Talabani, then head of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. Syrian officials try to exploit these ties to promote Iraqi policies that benefit Tehran and Damascus.

- Some analysts speak of a “Shi’ite Crescent” running from Iran, through Iraq and Alawite-ruled Syria, to Hezbollah-controlled Lebanon.

Both the Iraqi and Syrian governments share an interest in preventing their Kurdish minorities from pursuing greater autonomy.

Syria’s Kurds, although only a tenth of the population, are the second largest ethnic group and have long been the targets of government persecution. During the 1960s, the Syrian government stripped 100,000 Kurds of their citizenship.

Since the invasion of Iraq in 2003, which led Iraqi Kurds to establish their own government in northern Iraq, Kurdish nationalism has been on the rise in Syria. These developments would strengthen Kurdish calls for the creation of a greater Kurdistan, a development which neither Iraq nor Turkey would welcome.

Syrian and Iraqi leaders prefer that each state has an authoritarian government powerful enough to prevent the secession of their Kurdish populations, which would encourage their own Kurds to strive for greater autonomy.

They might also reason that authoritarian governments can better suppress Sunnis seeking to overthrow their two regimes.

Furthermore, economic ties between the current Baghdad and Damascus governments have also recovered from their previous lows.

In 2007, Iraqi-Syrian trade surpassed pre-war levels for the first time and has continued to grow since. Iraq has become a major importer of Syrian goods, with Syria becoming Iraq’s second-largest trading partner and Iraq becoming Syria’s largest trading partner.

Recent years have seen agreements on economic cooperation, including one that allows Iraq to resume pumping oil through Syrian territories for the first time since 1982.

Another arrangement creates joint free economic zones between Syria and Iraq that facilitate bilateral trade.

A July 2011 agreement aims to encourage joint investment projects. At the same time, Iraq and Syria agreed to form a permanent joint committee involving their trade ministries.

Iraqi and Syrian officials have also discussed developing a long-term strategic relationship in the railway, roads, and energy sectors, where they have many converging and complementary interests.

Despite their recently improved ties, several issues continue to divide Iraq from Syria.

- Sectarian divisions in both countries threaten regional stability and security.

- Political tensions persist between Iraqi and Syrian political leaders, including those in both ruling and opposition parties.

- In addition, border security is weak with migrants, militants and others readily crossing their frontiers. Political chaos in both countries has and will continue to challenge their relations.

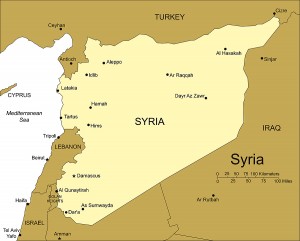

- The 363-mile border between Iraq and Syria remains the most contentious issue between these two states.

- Iraqi authorities have for years blamed Syrians for allowing insurgents to conduct cross-border attacks.

- In the aftermath of the U.S. led invasion of Iraq, Syria was a refuge for many Iraqi Baathists, and the Syrian Government was widely viewed as complicit in allowing Syria to be used as a base for jihadists to infiltrate Iraq.

- Now the Syrian authorities complain about Sunni extremists based in Iraq supporting the insurgency in Syria.

The departure of the U.S. military from Iraq at the end of 2011 has removed what had been an important impediment to the cross-border flow of militants and arms.