2012-11-16 By Richard Weitz

In addition to their security concerns, Russian officials are eager to reduce tensions on the Korean Peninsula and prevent abrupt regime collapse in the North in order to achieve their economic objective of greater integration with the prosperous East Asian region.

Russians hope that closer ties would encourage Asian investment and technology transfers that would help modernize the Russian economy.

In addition, the increased trade ties would benefit Russian consumers and exporters. Russian entrepreneurs envision revitalizing ties with the DPRK by converting it into a transit country for Russian energy and economic exports to South Korea and other Asia-Pacific countries. Russian planners want to construct energy pipelines between Russia and South Korea across North Korean territory.

They have also discussed linking a trans-Korean railroad with Russia’s rail system, which would allow Russia to become a transit country for South Korean trade with Europe that currently requires long-distance shipping.

For example, Russian policy makers have sought to link the Trans-Siberian and Trans-Korean railroads.

In April 2009, a Russian and a Chinese company signed an agreement building a line between Russia’s Khasan, the North Korean border town of Tumangang, and China’s Tumen. Before the onset of the latest crisis, they had hoped a North Korea company would join them in May 2009. The construction of such a link would allow Russia to become a transit country for South Korean trade with Europe, which now involves mostly by ocean shipping.

Russian policy makers describe their involvement in these regional economic projects as contributing to regional peace and security as well as prosperity. As Ambassador Ivashentsov asserted in January of 2009 with reference to these ventures, “There is no better way than long term economic projects to rebuild trust between North and South Korea.”

Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and other Russians hope that the Six-Party Talks could resolve the Korean nuclear dispute and establish peace and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula, spurring “the development of Russia’s Far East and Siberia regions.”

If the DPRK can normalize its relations with other countries, Russian businesses can use its territory as a platform for realizing their regional integration objectives. However, implementing these economic dreams requires normalization of the security situation on the Korean Peninsula.

In January 2009, Gleb Ivashentsov, Russian ambassador to South Korea, said regional stability is “crucial to Russia’s economic development,” especially plans to increase exploitation of the natural resources located in Siberia and the Far East. Comparing Russian energy ambitions in eastern Russia to “the development of the American West,” he explained that “Russia needs security guarantees in neighboring countries” for its realization.

Until then, Moscow’s economic ties and influence in Pyongyang will lag far behind that of South Korea and especially China, which provides North Korea with most of its foreign assistance, including energy, food, and other key commodities.

The DPRK can survive in the absence of economic ties with Russia because of China’s economic assistance.

Moscow’s influence in the Koreas is also diminished by its generally low diplomatic and economic weight in East Asia. Although U.S. diplomats seek to engage their Russian counterparts regarding Korean issues, their main interlocutors are in Tokyo, Seoul, and Beijing.

Some Americans are concerned about the proposed natural gas pipeline from Russia through North Korea into South Korea. The DPRK would gain hundreds of millions of dollars by allowing the project to pass through its territory, which it could use to buy more weapons and luxury goods, and would gain leverage to exert economic pressure on South Korea. But the pipeline could help revive cooperation among the parties and give them a stake in avoiding conflict.

Presently, Russian-DPRK economic ties are minimal.

Unlike China, Russia no longer provides direct economic assistance to North Korea. Soviet leader Michael Gorbachev’s decision to convert all Soviet trade with socialist countries to a hard-currency basis, a practice continued by the Yeltsin administration, precipitated a sharp deterioration in commercial exchanges between the two countries. Under Putin, Moscow suspended all military and nuclear energy cooperation with Pyongyang in line with international norms and sanctions.

Although eager to exploit profitable opportunities, Russia generally approaches its commercial relations with the DPRK from a market cost-benefit analysis perspective, which considerably constrains economic ties.

Until recently, a major obstacle to greater Russian-DPRK economic ties has been the large debt that North Korea accumulated during the Soviet period. For years, North Korean negotiators indicated they wanted Moscow to write off the entire $8 billion debt. The Russian government proposed various alternative debt settlement options to the DPRK, including exchanging the debt for investment or tangible property, but the North Koreans rejected these arrangements. Russian negotiators eventually agreed to waive most of the debt as an incentive to secure Pyongyang’s return to Six-Party Talks and to eliminate an obstacle to future economic cooperation.

In contrast to Russia’s frontier with China, the Russia-DPRK border is normally sealed. In November 1998, Russia, China, and North Korea signed a treaty to demarcate their territorial waters on the Tumen River, which borders the three countries. In August 2001, DPRK leader Kim Jong-il made headlines when he crossed through the border post of Hassan in an armored train en route to a 10-day trip to Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Along with China, Russia supports the free economic trade zone in the port city of Rason. Both Russia and China have aggressively developed supply routes to this city, with Russia investing at least $72 million as of early 2008 to restore its trans-Siberian railroad route and China making its own bid for the future trade volume with the construction of a new highway to complement its existing rail networks.

In 2009, Russia went further and pledged to spend $201.8 million to restore the railroad and renovate the city’s largest port. In early January 2010, Kim Jong-il visited the zone and designated Rason a “special city.”

The level of bilateral trade, which predominately involves Russia’s eastern regions, is well under $1 billion.. Russian policy is not to sell defense or nuclear energy items to North Korea, and China provides the DPRK with many other imports at subsidized prices.

In recent years, Pyongyang’s main export to Russia has been labor.

Thousands of North Korean workers are employed in Russia’s timber and construction industries. They provide one of the few means the DPRK has to earn foreign currency besides exporting weapons and inviting foreign companies to set up shop in North Korea, both of which are risky strategies since they expose the regime to external sanctions and internal democratic contagion, a fear that has impeded South Korean companies employing North Korean workers at the Kaesong Industrial Complex.

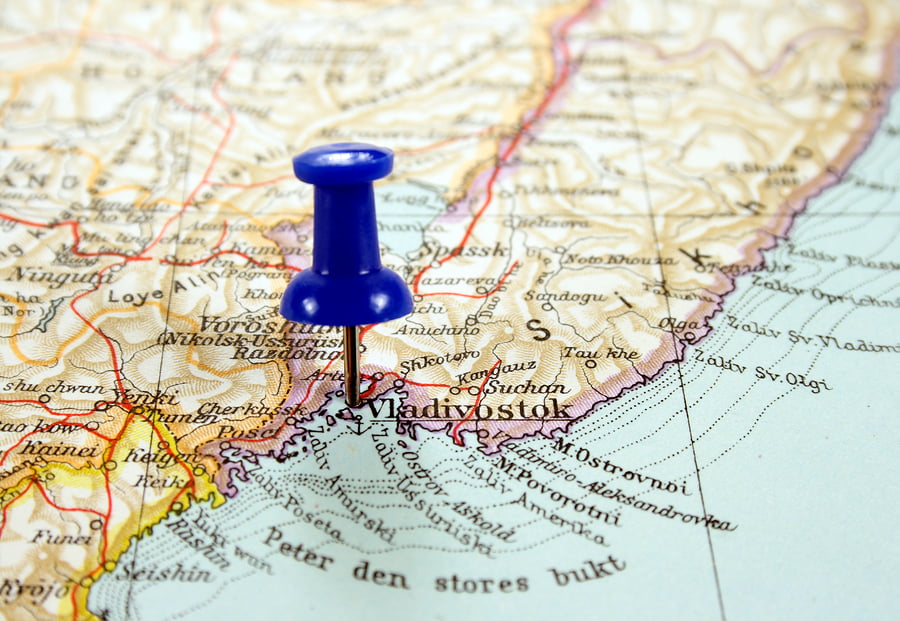

According to one Russian source, each of the 5,000 North Koreans in Vladivostok, who typically receive five-year visas, sends the DPRK government some $800 every month. Anything they earn beyond that, such as by undertaking odd jobs for local Russians, they can keep for themselves. In addition, over 1,000 North Koreans work in a network of remote logging camps in Russia’s Amur region, more than 1,500 kilometers from the Russia-DPRK border.

The camps are run by a Russian company that shares their proceeds with the North Korean government.

Some of these laborers tell reporters that they earn a few hundred dollars each month. Others complain that they are not paid regularly and they must work all day in unbearably cold weather with little to eat and frequent work-related injuries.

Thousands of North Korean laborers have reportedly deserted such camps during the past two decades. Some are lucky to find a sympathetic Russian family to stay with or gain the support of Russian human rights groups, but then they live in constant fear of being arrested and deported to North Korea.

Editor’s Note Expanding Russia’s economic stake in the Pacific is a major policy objective for the current Russian leadership.

A very good symbol of this was the hosting of the APEC conference in Vladivostok in the early Fall of 2012.

As one source put it:

The Kremlin’s probably most pressing motive for wooing APEC business to develop its Far East and East Siberia is to counterbalance China’s growing influence in the region. China has flooded local markets with cheap goods and is the main importer of Siberian resources. In a rare official acknowledgment of the threat of Chinese colonization, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev said last month that Russia must “protect” its depopulated eastern territories from “excessive” inflow of “citizens of neighboring countries.”