2013-01-29 by Robbin Laird

Given the size of the Pacific, and the significant reductions in the numbers of US air and sea platforms over the last decade, greater capacity to integrate air and sea platforms across the Pacific is a must.

And integration is not simply about the USAF, USN, and USMC, but is about the operational approach to allies as well.

The Size of the Pacific

The Pacific is certainly a key definer of 21st century strategic reality for the United States, and that reality is the tyranny of distance.

And the tyranny of distance challenges the persistent presence, which an effective 21st century defense and security strategy for the United States needs to be built upon.

As Ed Timperlake has underscored in our series on the SLD Forum on China and the Pacific:

The key to understanding any human conflicts in the Pacific is to first recognize both the natural power and size of that Ocean…..

The Pacific is nothing like the name –“Pacificum” or peaceful in Latin. It is a violent and expansive Ocean. Rounding the tip of South America. Ferdinand Magellan, in perhaps one of the more significant “name branding” mistakes in history pronounced the body of water he saw as peaceful….

The answer to the question how large is the Pacific is very simple — it is huge.

“The Size of the Pacific Ocean is Massive; it covers more than one-third of the earth’s surface, which is approximately 165 million square kilometers (about 65 million square miles). It extends about 15,000 kilometers (9,600 miles).”

The question of how dangerous and violent is the Pacific was answered by Sir Francis Beaufort in the 19th Century in his code measuring storms at sea “The Beaufort Scale.”

After being wounded several times and commanding a Royal Navy ship of war Beaufort became Hydrographer of the Royal Navy for twenty-five years. In fact some of his charts are still used to this day. Sir Francis was a visionary who specifically recognized the strategic importance of the entire Pacific and he also focused on the strategic importance of the Arctic.

His “Beaufort Scale” runs from 1 to 12 with a Force 12 being “Hurricane Winds.” –“Huge waves and sea is completely white with foam and driving spray greatly reduces visibility”.

However, in 2006 the Peoples Republic of China adopted a scale that goes to a high of 17 to acknowledge what they saw as the power of a tropical cyclone off their shore known as a “Chinese Typhoon.”

Consequently, all ocean going mariners, from early explores on war canoes, to Chinese Junks, to European sailing vessels to modern battle fleets must have a very healthy respect for the pure raw power and also extremely significant distances involved with the Pacific Ocean.

It is still very true that even a 21st Century Navy can only venture forth with ships and planes that are rugged, survivable and have the range to go up against both nature and in combat against a reactive enemy — it is not as easy as the US Navy makes it look.

A famous World War Pacific Typhoon makes that startling point. Historians have debated the number of USN Ships sunk by Japanese Kamikaze attacks during all of WW II in the Pacific. Their counts vary from a low of 34 to a high of 47.

Compare that Kamikaze fight against a reactive enemy over a almost a four year war with a US Task Force caught in a Pacific Typhoon in one 24 hour period.

In the Pacific Typhoon of December 18, 1944 three Destroyers capsized; the USS Spence, USS Hull, USS Monaghan, with the loss of most of their crew–over 700 hundred sailors perished. Additionally, 146 aircraft on Fleet Carriers were struck from the rolls because of damage. So yes being capable mariners along with rugged ships and planes makes a huge difference.

The Reduction in Numbers of Core Platforms

The decade of the land wars has seen investment in operations, logistics, manpower and equipment tied to Afghanistan-type operations, and an investment away from air and naval platforms.

This is simply not widely realized in the US policy debate, because the entry of air sea battle is seen by some as simply a return to business as usual prior to the “land war interlude.”

It is not; without shaping an effective strategy encompassing the air and naval platforms and forces of the United States, it will be impossible to deploy an effective fighting force, able to operate in a distributed manner and aggregated when necessary.

Across the board for the USAF, there are less fighters, bombers, tankers, air lifters, and ISR aircraft than needed for global operations. This means surging to operations, and exposing the US to crises where the surged forces are not present.

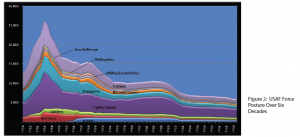

In a comprehensive look at the evolution of USAF forces since 1950, the Mitchell Institute provided a comprehensive look at the declining USAF inventory.

And with the very slow roll out of the F-35, this picture does not get prettier.

The situation facing the USN-USMC team is not much different.

The US is at historical lows in amphibious ships, and there are less capital ships all around. This means that any “Pivot to the Pacific” becomes a bit Houdini-like where assets can be moved from other areas into the Pacific, but at the expense of US capabilities in those other areas.

And in a world more likely to have crises than not, what this really means, is that forces will be deployed globally outside of the Pacific theater even if the best plans of mice and men is to move those forces “permanently” into the Pacific.

Seth Crosby of the Hudson Institute has provided a look at the policy consequences of the continued decline in US naval shipbuilding, and the slow roll out of less platform numbers. Numbers matter; con-ops matter; integration matters.

Platform numbers are crucial because of the presence problem and challenge; you cant be where you are not.

The Amphibs are the most useful of all USN ships for the kind of presence crucial in the Pacific. They can be used across the board in global contingencies, are in high demand from combatant commanders, and will be upgraded significantly as Ospreys, CH-53Ks and F-35Bs come to their decks.

A key indicator of the problem facing the USN-USMC team in any “Pivot to the Pacific” is the declining numbers of amphibious ships.

In the early 1970s, the USN had around 60 amphibious ships. Currently, the USN has 28 operational amphibious ships.

Shifting the Concept of Operations: A Strategic Choice

The tyranny of distance and the challenge of providing persistent presence will be beyond the kin of the United States with declining assets in the 21st century, if 20th century concepts of operations persist.

Air Sea battle provides a debate on templates, which can facilitate such evolution of con-ops leveraging the total force, seen from a USAF, and USMC-USN perspective or from a broader allied perspective.

And associated with air-sea battle discussions are other concepts such as the single naval battle, or enhanced regional presence.

If China and North Korea are the foci, then re-enforcing precision strike enterprise is the priority. The objective is to have as many forces, which can be deployed forward to strike Chinese or North Korean assets in time of war.

Precision strike coming by air, ground, and sea forces would be the means to strike as many aim points as possible to create escalation dominance and to win the “air-sea battle.”

If this is the approach then more traditional approaches will be prioritized and funded, such as the Carrier Battle Group, air expeditionary strike groups, and new systems like long range bombers which can load up on capabilities to deliver large strike packages are prioritized.

But what if the air sea battle really is about shaping a presence force with significant reach back to support a different kind of force structure and set of objectives?

Then precision strike deployed on as many platforms as possible – old and new – is not the means to the end. Rather, a different set of ends could well drive the new approach.

The key focus becomes presence forces able to operate across the spectrum of security and military operations. These forces need to be effective, agile, and scalable, with both significant interoperability within the region and reach back to surge forces operating on the fringes of the Pacific.

Assuming the approach is not primarily about striking Chinese and North Korean assets, but to constrain adversary operations in the Pacific and beyond, the tools needed are presence, partnership building and operations, an ability to put in place distributed, forward-deployed capabilities, which can rapidly reach back to additional capabilities able to augment them.

Perspectives on the Air-Sea Battle Concept

Richard Halloran in a very useful overview piece on the Air-Sea Battle Concept published in Air Force magazine, provided several insights into the approach. Halloran identified the strategic objective of the concept as follows:

The purpose of AirSea Battle is clearly to deter China, with its rapidly expanding and improving military power, from seeking to drive the US out of East Asia and the Western Pacific. If deterrence fails, AirSea Battle’s objective will be to defeat the People’s Liberation Army, which comprises all of China’s armed forces.

The Obama Administration and the Pentagon contend that war with China is not inevitable, which may be so, but a memo outlining the purpose of a previous AirSea Battle wargame left no doubt that the US is preparing for that possibility.

“The game will position US air, naval, space, and special operations forces against a rising military competitor in the East Asian littoral with a range of disruptive capabilities, including multidimensional ‘anti-access’ networks, offensive and defensive space control capabilities, an extensive inventory of ballistic and cruise missiles, and a modernized attack submarine fleet,” the memo read. “The scenario will take place in a notional 2028.”

There is only one “rising military competitor in the East Asia littoral,” and that is China. Long term, China offers the only real potential threat to US national security, far more than Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, or North Korea.

He then identified the crucial allied aspect of the concept as well.

AirSea Battle is not conceived as a “go-it-alone” initiative but one that will rely on allies in the Pacific and Asia, notably Japan and Australia, as US forces seek to overcome what is known in this region as the tyranny of distance. Americans who haven’t traveled the Pacific often have no notion of how far apart things are. For example, it is twice as far from Tokyo to Sydney, Australia (4,921 miles), as from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco (2,442 miles).

Being an Air Force guy, one interpretation of what this required is a better understanding and use of airfields in the Pacific region.

A critical element in the concept is to identify alternate airfields all over Asia that Air Force and Navy aircraft might operate from one day. US aircraft can be dispersed there, making life hard for a potential enemy such as China to select targets. Dispersed bases simultaneously would make it easier for an American pilot needing an emergency landing site to find one if his home base had been bombed.

In effect, the Air-Sea battle is really about the future of power projection in the region, and the challenges to which such forces might face.

One analyst has focused on what he calls Anti-Access, Anti-Denial capacities of China and others in the region, and concludes from this the need to have longer range strike forces. Although one wonders what happens to the core mission of US forces in the region, which is persistent presence.

For this analyst and his team, the objective of Air-Sea battle is clear: it is about maintaining conventional deterrence in the Pacific in the face of the rise of Chinese influence, both militarily and otherwise.

AirSea Battle must support overall US strategy for preserving stability in the WPTO. It must address the critical emerging challenges and opportunities that the PLA’s projected A2/AD capabilities will present, and to which currently envisioned US forces do not appear to offer a suitable response. It must account for the WPTO’s geophysical features, particularly its vast distances compared to Europe or the Persian Gulf region and the scarcity of US forward bases, which comprise a small number of very large and effectively undefended sites located on a handful of isolated islands, all within range of the PLA’s rapidly growing missile forces and other strike systems.

For the CNO, it is crucial to shape new payloads to deal with the evolving threat environment. And such payloads are a key element of the air-sea battle.

Our Air-Sea Battle Concept, developed with the Marine Corps and the Air Force, describes our response to these growing A2/AD threats. This concept emphasizes the ability of new weapons, sensors, and unmanned systems to expand the reach, capability, and persistence of our current manned ships and aircraft. Our focus on payloads also allows more rapid evolution of our capabilities compared to changing the platform itself.

For the authors of the Joint Operational Access Concept (JOAC), air sea battle is seen as a subset of the broader strategic problem, namely presence and access.

Nonetheless, the document contains a very clear statement with regard to what is seen as the focal point of the Air-Sea battle concept.

Recognizing that antiaccess/area-denial capabilities present a growing challenge to how joint forces operate, the Secretary of Defense directed the Department of the Navy and the Department of the Air Force to develop the Air-Sea Battle Concept.

The intent of Air-Sea Battle is to improve integration of air, land, naval, space, and cyberspace forces to provide combatant commanders the capabilities needed to deter and, if necessary, defeat an adversary employing sophisticated antiaccess/area-denial capabilities. It focuses on ensuring that joint forces will possess the ability to project force as required to preserve and defend U.S. interests well into the future.

The Air-Sea Battle Concept is both an evolution of traditional U.S. power projection and a key supporting component of U.S. national security strategy for the 21st Century.

However, it is important to note that Air-Sea Battle is a limited operational concept that focuses on the development of integrated air and naval forces in the context of antiaccess/area-denial threats. The concept identifies the actions needed to defeat those threats and the materiel and nonmateriel investments required to execute those actions.

There are three key components of Air-Sea Battle designed to enhance cooperation within the Department of the Air Force and the Department of the Navy.

The first component is an institutional commitment to developing an enduring organizational model that ensures formal collaboration to address the antiaccess/area-denial challenge over time.

The second component is conceptual alignment to ensure that capabilities are integrated properly between Services.

The final component is doctrinal, organizational, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, and facilities initiatives developed jointly to ensure they are complementary where appropriate, redundant when mandated by capacity requirements, fully interoperable, and fielded with integrated acquisition strategies that seek efficiencies where they can be achieved.

The capacity to work more effectively together across the services in delivering capabilities to the combatant commanders to support operations is really the point about Air-Sea Battle.

As the then Chief of Staff of the USAF, General Schwartz commented:

Our testing last year of an F22 in-flight, retargeting a tomahawk cruise missile that was launched from a U.S. Navy submarine, is an example of how we are moving closer to this joint pre-integration under our Air-Sea Battle concept.

(The USAF characterization of Air-Sea battle while Schwartz was chief of staff can be found here:

http://www.af.mil/shared/media/document/AFD-111110-018.pdf

Another characterization was provided by the CNO during the same presentation with General Schwartz.

Air-sea battle uses integrated forces for what we like to think as three main lines of effort. It’s integrated operations across domains to complete, as I said, our kill chain, but it’s also Air-Sea Battle lines of effort to break the adversary’s kill or effects chain. We want to disrupt the C4ISR piece of it; decision superiority.

It may be good enough alone if they can’t communicate or if something is causing an effect, if some signal is causing a nuclear disaster — our reactor to operate, how do we go in there and shut that down if the place is empty.

How do we get into that information superiority area? Defeat of weapons launch, get to the archer, or defeat the weapon kinetically to defeat the arrow.

And so looking at those three lines of effort, kind of summarizes how we approach that.

20120516_air_sea_doctrine_corrected_transcript

A very interesting Japanese perspective has been provided on Air-Sea battle in which the Japanese analyst sees the overall Chinese approach to projection of power in the region as the problem, not simply anti-access, anti-denial challenges with regard to the Chinese mainland.

From a Japanese perspective, challenges below high-end threat (i.e., China’s A2/AD capabilities) are also a major concern and seen as crucial to a deterrent strategy that the PLA would understand.

The National Defense Guidelines (2010 NDPG), released in December 2010, clearly indicates concerns about such challenges. In Defense Minister Toshimi Kitazawa’s remarks on the release of 2010 NDPG, he referred to the frequent activities/operations of surrounding countries’ military and other government organizations, as well as about the potential degradation of the security environment….

China’s opportunistic creeping expansion over such issues have become more disconcerting. With these concerns in mind, the 2010 NDPG highlighted continuous steady-state ISR operations and patrols in the East China Sea as highly prioritized operations for Japan’s “Dynamic Defense Force,” since capabilities and posture to “fight and win” in a high-end conflict may no longer adequately address such challenges. With increasing maritime and air activities in these areas, a “balance of activities” is necessary for maintaining strategic equilibrium between Japan and China.

counter_a2ad_defense_cooperation_takahashi

This Japanese perspective dovetails very nicely with that presented in the Pentagon document on the JOAC.

Air-Sea battle is a subset of a broader presence and engagement challenge.

An Australian perspective by Brigadier (Retired) Justin Kelly on the Air-Sea battle warns that new technologies will enter the equation and drive change as well.

The advent of hypersonic and high supersonic cruise missiles create a new challenge for air defense systems both ashore and afloat. The response times and performance required of air-defense weapons able to counter Mach 7 missiles are extreme and preparations to counter penetrating conventional aircraft are likely to be increasingly nugatory.

If Australia is to continue to prepare to counterattacks by another state, the nature of the preparations may need to be changed….

Fighting-China-AAJ-Vol9-No3-Summer-2012

A Way Ahead

What is needed is another look at geography and another way of thinking about military approaches with allies and collaborative technologies.

One way to think about this is to look at the forward side of the Pacific. The closer in side of the Pacific from Hawaii back involves the defense of the littorals and the key roles of Alaska and the Arctic.

Looking west of Hawaii, the United States operates in two strategic geometries.

The first strategic geometry involves the triangle from Hawaii to Guam to Japan. This triangle is at the heart of the ability of the U.S. to project power into the Western Pacific. With a 20th century approach which is platform centric and rooted in step by step augmentation of force, each key part of the triangle needs to be populated with significant numbers of platforms which can be pushed forward.

To be clear, having capability in this triangle is a key element of what the United States can bring to the party for Pacific operations, and remains fundamental.

But with a new approach to an attack and defense enterprise, one would use this capability differently from simply providing for PUSH forward and sequential escalation dominance.

Rather than focusing simply on the image of projecting power forward, the enablement of a strategic quadrangle in the Western Pacific is crucial to any successful allied or American Pacific defense and security strategy.

Competition among allies in the Western Pacific is historically rooted and as a former 7th USAF commander underscored, “history still matters in impeding allied cooperation.”

In spite of these challenges and impediments, shaping a strong collaborative quadrangle from Japan, to South Korea, to Singapore to Australia can shape new possibilities.

Enabling the quadrangle to do a better job of defending itself and shaping interoperability across separate nations has to become a central strategic American goal. This will require significant cultural change for the United States.

Shaping capabilities to operate in both in the 21st century will see the need to craft an effective synergy between US and allied assets, or we will suffer a Ben Franklin moment: “We will all hang separately or we will hang together.”

Rather than thinking of allies after we think about our own strategy, we need to reverse the logic.

Without enabled allies in the Western Pacific, the United States will simply NOT be able to execute an effective Pacific strategy. Full stop.

We are not about to have a 600-ship navy, and putting LCS’s into Singapore is a metaphor for the problem, not the solution.

The quadrangle of Japan, South Korea, Australia and Singapore can be populated by systems, which enable the shaping of a C5ISR grid that can able a honeycomb of deployed forces.

The population of the area with various sensors aboard new tankers, fighter aircraft, air battle managers, UAVs or aboard ships and submarines creates the pre-condition for shaping a powerful grid of intersecting capabilities.

Indeed, an attack and defense enterprise in the Western Pacific can be shaped which the United States can easily plug into, if indeed interoperability and mutually leveraging one another’s capabilities is seen as the strategic goal of the new Pacific strategy.

This will require culture change, and not only by the Asian powers.