2013-10-17 By Robbin Laird and Ed Timperlake

The P-8 is a new maritime surveillance platform built around an open architecture. It is also going into service in the Indian and American navies at roughly the same time.

This makes it a unique event for the two navies where a shared 21st century system is being incorporated into Indian and American naval operations at the same time, and as such can play a unique role in shaping a 21st century style of collaboration as well.

In other words, it is not just about technology but shaping shared understanding of concepts of operations for 21st century missions.

Facing 21st Century Challenges

Both the Indian and American navies face significant operational challenges in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The upsurge of maritime traffic associated with globalization has significantly complicated the problem of keeping track of vessels and threat identification.

The core security problem is posed by the nature of the “conveyer belt of goods and services” which transits the sea and then move by land. Securing the “conveyer belt” is a major security challenge in and of itself, but also because maritime terrorism can be woven into the conveyer belt in ways of concern for defending core “homeland” security stakes as well.

The comprehensive maritime security system, which evolves over time, is about managing a far-flung but central flow of goods and commerce across of “conveyer belt” which provides for the prosperity of nations. Raw materials pass through the system, semi-finished goods, various elements for the “just in time production” process, and final goods for delivery.

Asia is at the heart of all of these maritime developments: dynamic economic growth and development leading to greater reliance on shipping, containerization, mega-ports and crucial interdependencies with the United States and Europe.

Building an effective maritime security system must start with the challenge of security for the conveyer belt of goods and services. Maritime security is about security not just at sea, but in ports, inland waterways and in the transit of goods and services from ports inland via truck and train.

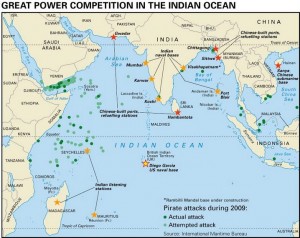

In addition, the rise of the PLA navy (PLAN) has brought the Chinese out into the Indian Ocean and enhances the threat from Chinese submarines.

And the growth of the numbers and quality of submarines by various players in the Indian and Pacific Oceans further complicates the challenge of protecting the fleet against underwater threats.

https://sldinfo.com/the-recent-russian-chinese-naval-exercise-a-new-phase-for-the-partnership/

https://sldinfo.com/chinese-military-power-report-highlights-growing-chinese-naval-might/

And with Chinese strategic submarines as part of the Chinese nuclear equation, there is concern by both India and the United States about the ability to track and deal with the Chinese underwater strategic threat as well.

The physical quality of the seas is not new, but the level of maritime traffic and the growth in naval forces by the PLAN and others is. In addition, the ability of terrorists to use the sea to mask their ability to strike targets on land was well highlighted by events in India. The 2008 Mumbai attacks demonstrated the utility of launching terrorist strikes from forces inserted from the sea.

According to a report by Bill Roggio, the projection of force from the sea was a unique aspect of this military style terrorist attack.

One of the more intriguing aspects of the attack is how the teams entered Mumbai. Reports indicate at least two of the assault teams arrived from outside the city by sea around 9 p.m. local time. Indian officials believe most if not all of the attackers entered Mumbai via sea.

Indian Coast Guard, Navy, Mumbai maritime police, and customs units have scoured the waters off Mumbai in search of a “mother ship” that transported one or more smaller Gemini inflatable boats used by the attackers. A witness saw one of the craft land in Colaba in southern Mumbai and disgorge eight to 10 fighters.

Two ships that have been boarded are strongly suspected of being involved in the attacks: the Kuber, an Indian fishing boat, and the MV Alpha, a Vietnamese cargo ship. Both ships appear to have been directly involved. The Kuber was hijacked on Nov. 13, and its captain was found murdered. Four crewmen are reported to be still missing.

In other words, a diversity of dynamics shape a challenging 21st century maritime environment for Indian and US forces.

The first is the simple growth in the numbers and size of commercial ships populating the “conveyer belt” creates a problem in determining which among the myriad of ships on the sea pose threats.

The second is the return of a significant ASW threat to the fleets and the expanded reach of the PLAN.

The Chinese are building out their infrastructure in the Pacific and Indian Oceans to support maritime operations, including those of the PLAN.

The third is the threat to the fleet from terrorists of various sorts. Usually referred to as the small boat threat, the attack on the USS Cole provides a significant reminder to both fleets of the wide-ranging threat from maritime traffic disguised as commercial shipping. Indeed, in the Bold Alligator 2013 exercise, “terrorists” used a commercial ship as part of the assault on the USN-USMC team.

https://sldinfo.com/bold-alligator-2013-shaping-a-21st-century-insertion-force/

The fourth is the challenge of piracy. The presence of pirates in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean is a continuing threat. The piracy threat is rooted in the upsurge of commercial shipping and the growth in the size of ships. The potential prizes at sea are going up and with it the desirability of grabbing a prize and negotiating with ship owners and insurance companies to gain wealth.

As Jonathan DeHart noted in a recent piece in The Diplomat:

As noted by The Economist 14 years ago, global piracy doubled during the 1990s, to 200 attacks per year as of 1999, with the bulk taking place in Asia. In 1999, almost three-fourths of global piracy took place in Asia. Indonesia was host to the largest number of attacks then as well. In 2004, the global total number of incidents spiked to 329, of which attacks in Indonesian waters accounted for 93.

When assessing these numbers, it is important to distinguish between degrees of piracy. On the lighter end of the spectrum are the sea-faring hooligans who conduct sloppy attacks on heavily trafficked coastal waters. These hoods favor the kinds of lanes where thousands of ships cruise – and drop anchor – between Indonesia and Malaysia, or in the South China Sea. These pirates usually attack as thieves in the night while ships are anchored and most crew members asleep.

On the other end of the spectrum, there is the more sophisticated and more troubling brand of piracy perpetrated by large-scale, well-coordinated global crime organizations. In these kinds of attacks, cargo worth millions of dollars is routinely stolen, as in the case of the Petro Ranger, an oil tanker that was robbed of $3 million worth of fuel en route from Singapore to Vietnam.

The need for cooperation between the Indian and US Navies is important as well as the ability to work with key allies in the region to deal with the full spectrum of threats.

As Professor Amal Jayawardane put it in his paper “Terrorism at Sea: Maritime Security Challenges in South Asia:”

In recent years piracy and maritime terrorism have become growing threats in the Indian Ocean, which is the locus of important international sea lines of communication. The Indian Ocean, the world’s third largest ocean, is of great strategic importance for the supply of crucial energy resources. About 40% of the global trade transits through the Indian Ocean. It provides major sea routes connecting the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean.

The Indian Ocean cannot be considered an “open” space as its access is controlled by several choke points such as the Bab el Mandeb, the Straits of Hormuz, the Straits of Malacca, the Sunda, and Lombok-Straits. In a world increasingly dependent on foreign trade, it is necessary to keep these choke points open at all times. The disruption of the Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) will have disastrous consequences to the global economy.

He then added that this required significant enhanced naval cooperation.

There is a strong naval presence of extra-regional countries as well as littoral countries in the Indian Ocean. While there is littoral resistance to extra-regional power presence, there is also intra-regional competition and rivalry among littoral powers. Competition among states for access and influence is unavoidable; however, it has become extremely important to develop cooperative maritime strategies to face common threats from asymmetric non-state actors.

The Physical Scope of the Challenge: The Key Role of ISR

The naval forces of India and the United States and their allies provide the physical presence assets, which can surge to a problem.

But determining where the problem exists or the nature of the problem requires first rate “domain awareness” or Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance overwatch.

The impact of ISR on a fleet was well articulated by Admiral Day of the USCG in discussing the impact of adding modern ISR to USCG operations.

Let’s talk about just the Eastern Pacific drug mission. Let’s just use that as an example. In the old days, we literally went down there and bored holes in the water, and if we came across a drug vessel, it was by sheer luck. It might be on a lookout list, and we might happen to see it.

Let’s fast-forward now to the 2000s and what we’ve started being able to do. By being able to fuse actionable intelligence, and not only that, but intelligence communicated at light speed.

So now, we’re to the point where we’re telling a Cutter to go point A, pick up smuggler B with load C. And we’re doing that in real time with delivery of a common operational picture, which has been fused with intelligence. That was unheard of 10 years ago.

The key is to be able to lay down an ISR grid over the area of interest using fixed wing, space-based or remotely piloted aircraft, or new robotic underwater or above water systems to generate the picture within which naval surface or subsurface assets can operate.

The challenge then is to tie the appropriate assets together with the identified threat or target and bring them together into a solid command and control system.

Collecting information is not the goal; the effort is to conduct more effective military and security operations against key targets of interest.

The challenge facing the Indian and US navies is rather simple: the geography to cover is vast, the traffic significant and the diversity of threats growing.

Put simply, the challenge of dealing with security in the Indian and Pacific Oceans is beyond the reach of any single naval power in the 21st century, and there is a crucial need for leading navies to work together to shape common ISR systems and to shape collaborative C2 for joint operations, as needed.

The sheer magnitude of the challenge posed by the Indian and Pacific Oceans can be seen from some of the maps we have included in this article and which highlight the nature of the geopolitical realities.

First, the Indian and Pacific Oceans conjoin at a crucial point in the world’s maritime traffic intersection and provides both a wide swath of water and many island chains populating that intersection as well.

A second map highlights the sheer size of the water involved and the scope of the challenge to provide effective ISR coverage of areas of interest.

A third map highlights the growth of infrastructure to support maritime forces in the Indian Ocean and the growing reach of the Chinese as well.

In other words, if one takes the maps as a portrait of the canvas of operational space, and considers ISR assets to lay down a grid on that space, the challenge for naval force is to surge to the problems which need to be resolved, and to do so in a timely fashion.

How the P-8 Plays Into This Picture

In an earlier piece, we looked at the P-8 as a new maritime surveillance platform.

The key points from that piece which we will leverage here are the following:

The P-8 unlike the P-3 has much greater speed and range, which means it, can surge to an area of interest much more rapidly;

The P-8 is an open architecture system, which means that it can evolve over time to incorporate new technologies and can adapt to the evolution of the fleet itself;

P-8 is being built to be part of a family of systems, and not as a single point of performance or in other words, other elements, manned and unmanned, will play their part over time in shaping the role of the P-8 within an evolving ISR system.

Notably, this platform is being introduced at virtually the same time within the Indian and American navies, which can provide a lynchpin for collaboration on shared ISR and C2.

This is not to say that both navies will use the system to support their own national or sovereign missions. It clearly will be.

But it puts in the hands of both navies at the same time a tool, which can evolve with the period ahead and shape new approaches to ISR and C2 necessary for the management of maritime security.

And because the P-8 is an open system and a part of a family of systems, the Indian Navy will certainly add new elements to its evolving ISR approach over time, and that some of those new capabilities clearly will be of interest to the US Navy as well.

In other words, by having a common baseline technology, the Indian Navy’s evolution will have a direct impact on the US Navy as well.

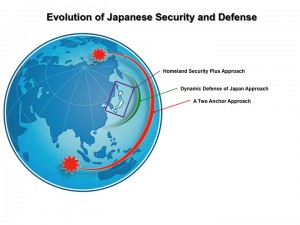

We argued in our forthcoming book that the Japanese Navy was being reshaped to deal with the Arctic and Chinese challenges and that the Japanese were moving eventually to seek maritime reach from the Arctic to the Indian Oceans.

The Japanese understand they will not do this by themselves but as a partner of the US Navy as well.

It is clear that such an evolution will be part as well of the growing reach of the Indian Navy in both Oceans of significance to India.

In effect, the P-8 will be part of the evolving naval collaborative framework between the Indians and the U.S. as well as with other allies.

The graphic to the left captures a way to look at this evolving situation.

What makes the P-8 an especially interesting platform is that it is a shared platform between India and the U.S. with others (such as Australia) likely to join in and this sharing of a platform can provide a tool for enhancing collaboration in the daunting task of shaping effective ISR for 21st century maritime missions.

The opportunity is inherent in the technology; the challenge will be to shape the collaborative approach and shared concepts of operations.

The threats require nothing less.

Editor’s Note: The information below from the Boeing website highlights the basic P-8 program to date.

The P-8, a military derivative of the Boeing Next-Generation 737-800, is the most advanced anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare aircraft in the world. It is a true multi-mission aircraft that provides long-range maritime reconnaissance capabilities. The aircraft’s speed, reliability, persistence and room for growth allow it to satisfy any customer’s current and future requirements. P-8 aircraft feature an open system architecture, advanced sensor and display technologies, and a worldwide base of suppliers, parts and support equipment.

With the P-8, Boeing has changed the way military aircraft are planned, designed and built. P-8 aircraft for the U.S. Navy and India are built using a first-in-industry in-line production process in Renton, Wash., that takes advantage of the proven efficiencies, manufacturing processes and performance of the highly reliable Next-Generation 737. Using established best practices and common commercial production tools enables Boeing to reduce flow time and cost while ensuring quality.