2014-02-07 Armin Tadayon

Despite Iran’s long history and culture, it is Iran’s nuclear program and attention-seeking officials that have been at the forefront of global politics in recent times.

This is certainly understandable given the Islamic Republic’s occasional belligerence.

We are, however, at an impasse on the negotiations with Iran over those nuclear weapons.

As President Obama stated in his State of the Union address, given the mistrust between the two nations, negotiations will be difficult.

Nonetheless, the opportunity is there for Iranian leaders to seize.

Should they choose to, they can rejoin the international community and peacefully resolve one of the leading security challenges of our time.

While most people prefer a peaceful solution to the Iranian nuclear program, we should not be too hasty in accepting statements by Iranian officials as fact.

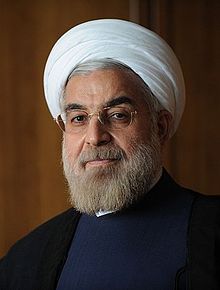

I understand that many in the West might be awed by the rational rhetoric of Rouhani given the low standards set by Ahmadinejad; however, acceptance without scrutiny is not the way to build trust.

It is simply unearned deference.

If we wish to build trust, we must be able to challenge our adversaries through dialogue, and a good starting place is Rouhani’s recent remarks.

In a recent interview, Fareed Zakaria asked Rouhani’s reaction to the potential of additional sanctions by the U.S. Congress.

In a very vague response, Rouhani stated that the U.S. Congress has a “long way to go before they fully appreciate and understand the Iranian people,” and that Iran does not want the bomb since the leader of the revolution has stated that the fabrication and stockpiling of nuclear weapons is religiously forbidden.

I believe Americans already know the Iranian people; just like any other nationality, Iranians are diverse, educated, and admirers of liberal ideals.

Who the U.S. Congress and the American people must understand is Iran’s ruling clergy.

An initial starting point in fully appreciating and understanding the Iranian clergy is by examining the Supreme Leader’s fatwa regarding nuclear weapons.

A fatwa is a ruling on a point of Islamic law by a recognized authority. It is important to understand, however, that a fatwa is binding only on the followers of the mufti (issuer of the fatwa).

Since Khamenei is the Supreme Leader of Iran, and since he believes that he is the spiritual and political leader of the Muslims of the world – a belief not shared by the Muslims of the world – one can argue that his legal interpretation is, at a minimum, binding on Iran.

If one is being acquiescent, the inquiry can stop here.

My first point of contention, however, is the fact that since a fatwa is not perpetually binding, when Khamenei dies, whatever force his religious rulings may have had will die with him.

Second, the changing of fatwas is common practice among Shiite jurists, as is the issuance of contrary religious holdings by other muftis.

Third, Khamenei has numerous verbal holdings regarding nuclear weapons. In 2005, Khamenei stated that Islam does not allow Iran to produce the atomic bomb. By 2006, however, Khamenei’s emphasis had change from the production of nuclear weapons to their usage: “We [Iran] believe that using (emphasis added) nuclear weapons is against Islamic rulings.”

In 2009 Khamenei again stated: “We announced that using a bomb is forbidden in Islam,” and similarly, in 2010, Khamenei repeated: “using such weapons of mass destruction is forbidden, is haram.”

Accordingly, although Iranian officials might argue that nuclear weapons are religiously forbidden, the Supreme Leader appears to be making a very fine distinction between the haramful nature of using nuclear weapons as opposed to merely producing and owning them.

Finally, even if we were to disregard the discrepancy in Khamenei’s statements and Rouhani’s recent remarks, we should not ignore the Shiite tactic of “Khod’eh” which permits one to deceive and trick one’s enemy into a misjudgment of one’s true position.

The clearest example of the use of Khod’eh was by Khomeini.

Despite promising improved conditions for human rights and assuring that the clergy would not govern Iran, after overthrowing the Shah, Khomeini clung to power and simply stated that he had employed the tactics of Khod’eh.

As recently as late 2013, the Fars News Agency, an unofficial mouthpiece for Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, published an article justifying the use of Khod’eh.

I am not arguing that the regime in Tehran is deceiving the international community.

What I am advocating is the importance of reasoned scrutiny, or what President Obama referred to in the State of the Union as verifiable actions by the Iranian regime.

Armin Tadayon is a DC-based law school graduate with a concentration in homeland and national security law.