2014-03-18 While attending the Williams Foundation Seminar on Air Combat Operations: 2025 and Beyond, Dr. John Lee of the Kokoda Foundation provided a base line brief on how to understand the Chinese challenge, military and non-military to the region.

The contribution of Aussie airpower and associated military capabilities was to be understood in both national and coalition terms as a contributor to deal with such challenges.

Dr. Lee highlighted several key elements of the PRC challenge, which were included in his presentation, which is provided below.

The key points with regard to the PRC strategic view were as follows:

- All things being equal, and assuming no disruptive developments to regional trends, America is here to stay strategically and militarily for the reasons that I gave.

- China’s enduring vulnerability is not its sovereignty territory but its inability to secure unfettered access to the commons by itself, and inability to defend its unfettered access to the commons.

- These vulnerabilities will persist whilst America and its system of alliances and security relationships remain in Asia. And these relationships seem to be robust and enduring.

Dr. Lee then underscored how he believed the Chinese were seeking to achieve their objectives in the period ahead:

- You create the reasonable expectation that any significant military conflict with China will cause severe disruption to economic prosperity in the region – thereby lowering the political will in Washington or other regional capitals to contemplate military intervention in the first place.

- You improve your military capacity to seize disputed islands before an organised and effective military counter-response is possible. In doing so, you raise the chances that any counter-response once territory has already been seize will be prohibitive.

- You gradually exercise de facto sovereignty and control over disputed areas in the East and South China Sea in a manner in which each individual move is never extreme enough to provoke a military response.

Now to the presentation itself:

My brief here is to speak about how China thinks about the region, why it has the strategic doctrine and operational concepts that it does, and how the PLA Air Force fits in.

My talk is NOT about what the true state of its military capabilities might be, or how they will fare against those of the U.S. and other powers; whether it can actually execute its operational concepts; or whether its civilian and military institutions are up to the task of modern, high-intensity warfare.

There are many of you who will know a lot more about these issues that I do, so I won’t pretend otherwise.

Let’s begin in the period when the Cold War ended. I know this may seem a little historical but bear with me because it is directly relevant to how the Chinese think about the region today.

Remember what has just happened to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). They have survived their own revolt in 1989 when there were protests in about 350 out of 450 cities involving millions of people. The CCP hung on by a fingernail. For the regime to survive, it needed to tap into the regional and global trading system to modernize its economy – this from the background of a country that had spent most of the post-WWII period alienating the majority of powers in the region.

So the Chinese were forced to consider their place in the modern, somewhat wary liberal order from a position of some ignorance. But they began badly. Throughout the 1990s, when the Chinese surveyed the outside environment, they made two assumptions that proved to be fundamentally incorrect.

The first was that Asia and the world would become far more multi-polar if not polarized. With the Cold War ending, there was near consensus in Beijing that American allies would move in a more independent direction, and that the US might even be forced to wind down its presence in Asia.

In doing so, China misread the drivers and psychology of American foreign policy, one of which is to maintain its preeminent strategic role in Asian maritime domains essential to its economic interests.

China also misread the psychology and strategy of the rising Asian economic states. States like Japan, South Korea, Malaysia and Singapore basically wanted a peace dividend – to get rich and to largely outsource security to America.

So to the amazement of Beijing, even as American spending went up in absolute terms and as a proportion of global military spending in the post-Cold War period, and the capability gap between America and the rest of the world widened, few rising states in Asia seem particularly concerned about it all.

In fact, they encouraged it. And except for incidents such as the Filipinos kicking the Americans out of Subic Bay in 1992, most allies seem happy to facilitate a robust American presence on their sovereign territory.

In other words, rather than balancing against America as China expected, countries were maneuvering to keep America on top in Asia.

The second mistake that China made, which follows on from the first, was that they had a fairly narrow view of national interest and security. In particular, they viewed national security as protecting the sovereignty of their continental territory, including holding on to Tibet and Xinjiang. Of course, there was always Taiwan, but that is more a political and emotive issue for the CCP.

In particular, it took them awhile to understand that modern, open economies in Asia depended on maritime rather than continental trade – a difficult realisation for a country that has been a continental power for thousands of years.

Even when China became a net oil importer in 1993, it took a while for Beijing to realise that one’s national interest depended on unfettered access to the regional and global commons, and that one’s core national interests were fundamentally threatened if one were ever denied free access to these commons.

If China understood this, it would have immediately realised why so many countries were prepared to outsource security to the Americans – since only the U.S. could offer stability and guaranteed access to the commons.

Of course, it is now clear to Beijing that the commons is more than just sea-lines-of-communication (SLOCs) – it’s also air, space and cyber.

Finally, one important realization has finally dawned on the Chinese. If we put aside arguments based on the greater attractiveness of American political values over Chinese ones, we need to remember that the grand strategy – if there is such a thing – of pretty much every Asian power for centuries has been to prevent the rise of another Asian hegemon.

In the modern day, this is extended to preventing any Asian hegemon controlling the regional commons. Not geographically based in Asia provides a structural and strategic reason why most Asian countries prefer to outsource security to America rather than to an Asian hegemon.

Moreover, because of China’s pure size, and potential power, there will be no balance in Asia without America if China continues to rise as rapidly over another two decades (a questionable assumption in my view).

In other words, hedging against China and closer to America was always going to be the likely response of every major trading power in Asia.

This leaves China as a strategically isolated rising power despite its economic importance to the region. It is the second largest economy in the world without any genuine strategic allies to speak of (unless you count North Korea). That is unprecedented in recorded history since large economic powers generally exert a strategic pull.

So before I get on to the military dimension of all of this, let me summarize the Chinese view of the region as I see it.

All things being equal, and assuming no disruptive developments to regional trends, America is here to stay strategically and militarily for the reasons that I gave.

China’s enduring vulnerability is not its sovereignty territory but its inability to secure unfettered access to the commons by itself, and inability to defend its unfettered access to the commons.

These vulnerabilities will persist whilst America and its system of alliances and security relationships remain in Asia. And these relationships seem to be robust and enduring.

So even though they have achieved many of the economic goals they set for themselves, the Chinese misread the post-Cold War strategic environment and have a weaker hand than they would have expected. And like all of us, if we get something important wrong, it tends to have a profound and lasting impact on how we look at things. And the Chinese are no different.

But the Chinese are not without strategic options. And this is where the lessons – for Beijing anyhow – of Subic Bay comes in.

I know it’s a complicated story, but essentially, the Americans left Subic Bay – then the largest American overseas base – without a shot being fired. The American vulnerability from the Chinese point of view is that the US will not, and probably cannot afford to go to war in order to maintain its military footholds on sovereign territory if they lose the support of the host government.

So if I were the Chinese, this is how I would be thinking… And in fact, the following is how I believe they do think about strategy in the region. The fundamental principle is to:

Lower American political will to intervene in a military conflict; or lower the political will for regional states to resort to reliance on American military assistance and protection.

How do you achieve this?

There are a number of ways.

You create the credible expectation that you can impose prohibitive military costs on American military assets; or that you can impose prohibitive costs on the military assets of the American ally with or without American attempts at intervention.

You create the reasonable expectation that any significant military conflict with China will cause severe disruption to economic prosperity in the region – thereby lowering the political will in Washington or other regional capitals to contemplate military intervention in the first place.

You improve your military capacity to seize disputed islands before an organised and effective military counter-response is possible. In doing so, you raise the chances that any counter-response once territory has already been seize will be prohibitive.

You gradually exercise de facto sovereignty and control over disputed areas in the East and South China Sea in a manner in which each individual move is never extreme enough to provoke a military response.

If you can achieve all that, you will dilute the relevance and reliability of the American alliance system, consolidate your control over the immediate maritime commons of Asia, and eliminate your perceived vulnerability in these immediate SLOCs.

And if you achieve that, it is a first and important step to kicking American out of Asia without a shot actually being fired. So American strategic and military pre-eminence in Asia will end with a whimper – like Subic Bay in 1992 – and not a bang.

So bear in mind the inferences you should have from the Chinese view:

They don’t have to be able to win the battle, let alone the war, to achieve their political and strategic objectives – just be able to impose prohibitive military and/or economic costs.

They don’t need military capabilities to defend all their economic interests such as commercial shipping into China through SLOCs which is impossible. They just need enough military capability to cause prohibitive damage to commercial shipping for other countries – a far more feasible tactic.

Let’s now get on to some Chinese military doctrine and concepts – and I’ll link it back to what I just said. The first one you might have heard about is the contradictory sounding ‘Active Defence’.

Active Defense is an operational guideline for military strategy that applies to all branches of the PLA including the PLA Air Force. It states that China’s military engages in a policy of strategic defence and will only strike militarily once it has been attacked. But there are two conditions attached to Active Defence.

First, it states explicitly that such a defense posture is only viable if connected to an offensive operational posture.

In other words, as far as the PLA is concerned, an effective counter-attack is only possible when the PLA is able to negate the enemy’s offensive military assets in predetermined areas.

To put it in another way, if a man is running at you with a knife, you don’t go for his hand. You ensure that you are pre-emptively positioned to stab at his legs.

Second, Active Defence explicitly states that a first strike that triggers a Chinese military response need not be military in nature. It can be political, such as a Taiwanese declaration of independence. In other words, and under Active Defence, a Chinese military reaction is a legitimate response to political provocation.

The next term you might have heard about is ‘Local Wars under Conditions of Informatization’ (or ‘Local Wars’ for short). While Active Defence provides the basic strategic posture for the PLA, Local Wars is more an operational concept and has been the official operational doctrine of the PLA since 1993.

Local Wars assumes that foreseeable wars for China will be located geographically, primarily along China’s periphery. It will most likely be limited in scope rather than a total war, limited in duration and means, and conducted under ‘conditions of informatization’.

To quote the American DoD, this simply means “conditions in which modern military forces use advanced computer systems, information technology, and communication networks to gain operational advantage over an opponent” – in other words, the operational doctrine refers to “high-intensity, information-centric regional military operations of short duration.”

This outlook basically arose when the Chinese observed American operations during the first Gulf War in 1991 and saw this as the beginning of a new era of warfare in which technology revolutionised the way militaries were organised, led and fought.

Moreover, because of the economic and nuclear constraints on the conduct of total war, the Chinese are convinced that future wars will be fought under these localised conditions to achieved limited political goals such as the settlement of territorial disputes.

Credit Photo: Kyodo News, 2011

Many of you will know more about China’s military modernisation than I do, but it seems to me that the PLA’s ongoing modernisation has essentially occurred along the lines of the Local Wars Doctrine.

But it’s still essential to place these doctrines and concepts within the notion of the overarching strategy: the advances in military capabilities are ultimately in furtherance of the broader political strategy of retaining the capacity at any stage of a conflict – particularly the opening stage – to inflict prohibitive military and economic costs on a more powerful enemy.

So in any military capability comparison or war-gaming, this has to be taken into account.

Finally, just a comment about Chinese thinking on air power:

As you would expect, the PLAAF has moved from thinking about air power being used to repel air and ground invaders over its continental territory (i.e., land based defence) towards deterrence, strategic strike at sea, and providing cover for landing operations.

So if you take the PLAAF’s concept of “integrated attack and defense” which is part of the PLA’s Active Defence posture, joint counter-air strike campaigns will take place alongside the Second Artillery’s anti-ship ballistic missile capabilities in order to defend China’s territorial and sovereignty claims, and limit the options available to the U.S. in terms of strike, access and maneuvering capabilities.

Likewise, it seems that much of Chinese thinking on air-craft carriers is to use them to provide air cover for landing operations within the South China Sea. Based on limited capabilities of the air-craft carriers and the planes they can service, experts in the US and India tell me that Chinese air-craft carriers will have further battle relevance beyond the South China Sea.

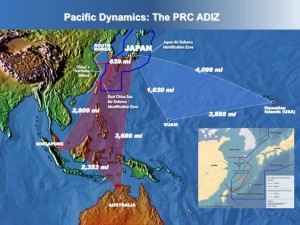

So in summary, the PLAAF is seen as an integrated part of China’s A2AD capabilities along with the PLAN and the Second Artillery. Remember that in the Active Defence doctrine, China needs to execute these capabilities beyond the First Island Chain (which stretches from Japan to Philippines to the north of Indonesia) in order to deter advances against it within the First Island Chain.

Of course, there is a lot we don’t know about the actual capabilities and battle-readiness of Chinese forces. They are pretty much untested beyond a couple of small operations some time ago: when Chinese forces captured the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam in 1974; when they occupied Mischief Reef in 1995.

Moreover, Chinese doctrine and concepts is deeply susceptible to miscalculation, not just in terms of their capacity to inflict prohibitive costs on the enemy, but also what the level of damage needed to constitute prohibitive costs might be. In other words, it will be very easy for the Chinese to incorrectly assess the political will of America during any crisis.

For our look at some of the same issues raised by John Lee see the following:

https://sldinfo.com/understanding-the-chinese-military-puzzle/

https://sldinfo.com/the-pla-goes-feet-wet-testing-the-pla-in-real-world-conditions/

https://sldinfo.com/flipbooks/StrategicInflectionPoints%20May%202012/

https://sldinfo.com/the-chinese-challenge/

https://sldinfo.com/the-evolution-of-prc-air-power-an-overview-from-retired-ltg-deptula/

This presentation is published with the permission of The Williams Foundation.