2014-07-15 By Robbin Laird

It was a pleasure when visiting the Second Marine Air Wing in June 2014, to be able to visit with the VMU-2 squadron and to get a perspective on how UAVs are part of the future of combat, and not learn that they are the future of combat.

Clearly, the squadron is looking at the mix of airborne support elements to the MAGTF, the F-35B, the legacy fighters, Ospreys, rotorcraft, the KC-130J and UAVs, and working on how to shape the UAV contribution within an evolving context.

The CO of VMU-2 is Lieutenant Colonel Kris Faught.

The CO most recently served with VMM-266 as the Air Combat Element Operations Officer for the 26th MEU (his full biography can be seen at the end of the article.)

The discussion was wide-ranging and focused on the various dynamics of change affecting the evolution of UAVs within the USMC and their potential role in operational support.

The Mission Statement for the squadron highlighted its contextual support role, both now and evolving future capabilities. The Mission of VMU-2 is described as follows:

To support the MAGTF Commander by conducting electromagnetic spectrum warfare, multi-sensor imagery reconnaissance, combined arms coordination and control, and destroying targets, day or night, under all-weather conditions, during expeditionary, joint and combined operations.

The CO highlighted some key limitations facing UAVs for the USMC, and identified what he saw as a solid growth path going forward.

He started with a discussion of the value of the Shadow UAV and its experience for the USMC.

Clearly, Shadow has provided important operational experience, yet the Shadow is not congruent with where the USMC is headed. “It is clearly not expeditionary; and looks like it has been designed by a tanker.”

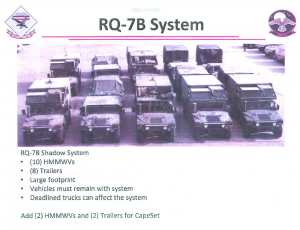

Just looking at the following slide certainly underscores the limitations on Shadow as an EXPEDITIONARY system.

And in an earlier interview with Major Cuomo, head of the Infantry Officer’s Course, the limitations of Shadow as an expeditionary element was seen as limiting the strategic direction of the USMC as a Tilt-rotor enabled force.

As we noted with regard to VMX-22 and IOC collaborative exercises testing long raid insertion:

Prior to the second exercise in Camp Blanding, FL that DCA and his team offered IOC their full support. Notably, they were offered a “Shadow,” unmanned aerial system (UAS for the second experiment. The idea was to operate in a very humid and tropical objective area similar to many areas in the Asia-Pacific region.

This exercise was very helpful in highlighting the limitations of the “Shadow” for the type of expeditionary operations being tested in the exercise. And as well, it highlighted what kind of UAS support asset the GCE would find most useful to such operations.

And according to the CO of VMX-22, these considerations are crucial for Aviation thinking about the way ahead with unmanned aircraft for the Corps.

This has meant that the USMC is looking for a more agile UAV with a significantly reduced footprint to support its operations.

Currently, the squadron is working with the RQ-21A Blackjack to work through ways to evolve an expeditionary support capacity from its UAVs.

Notably, 2nd MAW Forward is using working with an Early Operational Capability (EOC) run up to the RQ-21A in Afghanistan to gain operational experience in order to help shape the way ahead for the UAV role within the USMC.

The principle differences are software and some ship compatibility issues with launcher and retriever between the EOC system and the RQ-21A system.

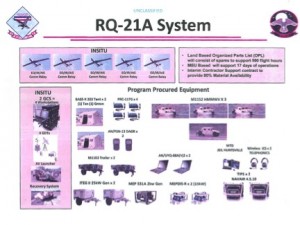

In the slides provided in the briefing by Lt. Col. Faught, a number of key characteristics of the RQ-21A were highlighted:

- Early Operational Capability

- Max Control Range of 93 kms or 50 nms

- Service Ceiling of 15,000 ft MSL

- Airspeed of between 55 and 110 knots

- An endurance of up to 15 hours

- Operates with a low noise signature.

A key quality of the Blackjack is its non-proprietary payload system.

“The payload bay is not patent-protected. This means that L-3 is building payloads. Lockheed Martin is building payloads. Little one off shops in San Diego are building payloads.”

And clearly the trend line, which the Marines would like to see, is an ability to shape modular payloads to provide for the support missions envisaged for UAVs.

Currently, the Blackjack carries the following types of payloads:

- Electric-Optical

- Mid-Wave Infrared

- IR Marker

- And the Secondary Payload Bay Supports: CRP and EW.

The approach to support the RQ-21A is considerably less than the Shadow and clearly allows the Marines to work on their expeditionary support approach.

With regard to the RQ-21A, the squadron was working with industry to shape ways to enhance capability.

We are looking at size, weight, power tradeoffs to enhance overall platform capability.

Currently, we are at 135 pounds with the platform and we could go as high as 165 which would give us more payload to carry onboard.

Lt. Col. Faught emphasized throughout the discussion the need to evolve the payloads along with other key aviation capabilities being shaped for the MAGTF. He especially felt that EW payloads will be increasingly of interest going forward.

And he felt as the F-35B joins the force along with the Ospreys, the opportunity to rework evolving UAVs to operate with these more expensive combat systems would be significant.

An ability to command UAVs from Ospreys is significant and the UAV can be launched in advanced of Ospreys entering an objective area and providing a wingman or escort function for the Ospreys.

The same could prove true for the F-35Bs dependent upon the mission set.

The core point is that the squadron is not thinking as an island.

But there is a core challenge facing the squadron in terms of shaping an expeditionary approach.

The support equipment is provided by different parts of the USMC, whether they be trucks, energy support or C2 and these different parts are not bought with the UAV in mind. Such an approach clearly will not maximize the expeditionary footprint for the UAV.

Lt. Col. Faught also focused on shipboard support by UAVs.

Clearly, one way to think about this is flying the son-of-Scan Eagle, which is the RQ-21 off of ships, for it has been designed to be recovered shipboard. But he felt that support to an amphibious fleet could come from large land-based UAVs as well.

“We could launch an UAV from North Carolina or Europe and it could cover our area of interest in Africa, for example. It would be providing shipboard support but does not need to be launched from the ship. We need to think through operational concepts to come up with the most effective and sensible approach.”

He emphasized as well some of the misconceptions about UAVs.

One of these is cost.

“Perhaps the per unit cost looks good; but if you lose a lot of them, the cumulative cost does not look so good.”

And he argued that the UAVs are really not good airplanes.

If you asked a child what that thing on the tarmac is and he would say it is an airplane.

It is an airplane.

But it is not built like an airplane. Indeed, they are built with unique and often not so reliable parts.

It would be good in the future if we could tap into a broader aviation construction industry to get parts for future UASs or UAVs.

There are other limitations as well affecting training and operations.

“Amazingly waterproofing is a problem with the RQ-21. And climb rates are difficult which means that you want to operate in relatively flat terrain”

A particular vexing problem facing UAV operators in the United States is to be able to operate UAVs in civil airspace. The FAA has been mandated by Congress to be able to do so by 2015.

The squadron has built a capability to do just that and recently a NASA team came to Cherry Point to see how the Marines carried this off.

I was able to visit the control room where the Air Traffic Controllers managing the flight of USMC UAVs into the civil airspace in their region.

We have a ground-based sense and avoid system for our UAVs here at Cherry Point.

The only other place in the US where you can find such a system is at Cannon Air Force Base in New Mexico.

I then visited the hanger and the RQ-21A on the tarmac.

I had a briefing from the pilot, Sergeant Lopez who explained the challenge of flying an UAV.

It was clearly a very cool digital experience, but guiding an out of sight airplane has its challenges.

When asked what was the next challenge he was looking forward to with the program, the answer came quickly: “I want to be the first at-sea pilot to operate the aircraft!”

A final issue, which we discussed with a Prowler pilot in the room, was the whole challenge of transitioning the Prowler experience into the UAV squadron and the F-35B squadron. Clearly with the migration of electronic warfare to what Ed Timperlake has called “Tron Warfare” change is under way.

The USMC clearly understands this.

As Col. Orr, then the CO of VMX-22 put it in a presentation to the Air Force Association Mitchell Aerospace Institute:

Col. Orr also discussed the USMC effort to merge the complementary capabilities of two traditionally separate, very separate communities.

We have signals intelligence professionals, primarily ground-based radio battalions who report back up through Title 50 authorities.

And then we have a separate group that does electronic warfare, notably the EA-6B Prowler conducting tactical electronic warfare.

Those two communities traditionally haven’t really talked much.

We are bringing them together in the same facility called the Cyber/Electronic Warfare Coordination Cell (CEWCC).

That Cyber/Electronic Warfare Coordination Cell provides the MAGTF commander the ability to deconflict and conduct operations within the electromagnetic spectrum at a tactical level.

At a tactical level, the CEWCC allows us to be able to combine cyber and electronic warfare effects and have the commander make decisions ranging from listening to deception to jamming.

Prowler experience as well as infrastructure needs to be folded into the way ahead, a subject, which we hope to pursue in the near future.

As Lieutenant Colonel Faught put it: “We need to find ways to exploit the analytical infrastructure which has supported Prowler and take that forward into the 21st century approaches we are now shaping.”

Lieutenant Colonel Faught

Lieutenant Colonel Faught enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve in 1993 and served in 6th Engineer Support Battalion in Portland, Oregon. He was subsequently commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in 1997 after graduating from Oregon State University. Soon after, he attended Basic Officer’s Course 5-97 and Infantry Officer Course 3-98 prior to assignment to flight school in June of 1998. In February of 2000, he was designated a Naval Aviator and reported to Camp Pendleton for initial training in the AH-1W.

During his first assignment at HMLA-167, MCAS New River, he deployed as part of HMM-261 in 2002 in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. Upon return in September, he attended Tactical Air Control Party school and became the battalion air officer for 1/8. As such, he deployed with the 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) to Iraq, Djibouti, and Liberia. From there, he executed orders to Camp Pendleton where he joined HMLA-367 in December of 2003. Throughout this tour, LtCol Faught deployed twice to Iraq in 2004-2005 and 2006-2007, where he served at Al-Taqaddum, Al-Qaim, and Korean Village.

In 2007, LtCol Faught reported to The Basic School and served as the Air Officer, Deputy Director of Warfighting, and Commanding Officer for Companies D and B until 2010. He then reported to MAG-29, upon completing refresher training at Camp Pendleton, and was assigned to HMLA-467 as the Operations Officer and Executive Officer. At the completion of that tour, he was attached to VMM-266 as the Air Combat Element Operations Officer for the 26th MEU.

In January 2014, LtCol Faught reported to MAG-14, where he was assigned as the Executive Officer of VMU-2.

His personal decorations include: Meritorious Service Medal, Air Medal, and 2 Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medals.

For videos of Shadow and Scan Eagle operations to be found on Second Line of Defense see the following:

https://sldinfo.com/shadow-company-uas/

https://sldinfo.com/prepping-scan-eagle-for-flight-in-afghanistan/

https://sldinfo.com/launching-scan-eagle-in-afghanistan/

https://sldinfo.com/operating-scan-eagle-in-afghanistan/

The first two photos are credited to Navy Media Content Services and the next three to 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing & Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point.

- In the first photo, the RQ-21A Small Tactical Unmanned Air System (STUAS) is recovered with the flight recovery apparatus cable aboard the San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock USS Mesa Verde (LPD 19) after its first flight at sea. Mesa Verde is underway conducting exercises (2/10/13).

- In the second photo, the MKIV launcher prepares to launch the RQ-21A Small Tactical Unmanned Air System from the flight deck of the San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock USS Mesa Verde (LPD 19) for its first flight at sea.

- In the third photo, Lance Cpl. Kirk Humes, left, and Cpl. Johnnie Hays, right, lift an RQ-21A Blackjack prior to launch at Marine Corps Outlying Field Atlantic’s flight line, March 21, 2014. Humes is an UAV maintainer and Hays is an UAV operator, both with Marine Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Squadron 2 (3/21/14).

- In the fourth photo, Cpl. Johnnie Hays adjusts the RQ-21A Blackjack on its launching system at Marine Corps Outlying Field Atlantic’s flight line, March 21, 2014. Hays is an unmanned aerial vehicle operator with Marine Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Squadron 2.

- The final photo shows an RQ-21A Blackjack belonging to Marine Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Squadron 2 sits on the flight line of Marine Corps Outlying Field Atlantic, March 21, 2014. The Blackjack is eight feet long with a wing span of 16 feet and can hold payloads up to 25 pounds.