2014-11-01 During our visit to The Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center, we were able to discuss the role of rotorcraft on the carriers and the training to that role at NSAWC with CDR Herschel “Hashi” Weinstock, current Department Head for SEAWOLF, NSAWC’s Rotary Wing Weapons School.

CDR Weinstock is a native Virginian with an undergraduate degree from the University of Virginia and a Master of Science degree from the University of San Diego.

Designated a Naval Aviator in 1996, his early flying tours include service with the HS-15 Red Lions in Jacksonville, Florida; the HS-10 Warhawks and HS Weapons and Tactics Unit in San Diego, California; and the HS-14 Chargers in Atusgi, Japan.

He commanded the HSC Fleet Replacement Squadron in San Diego, HSC-3.

His staff tours include duty with Carrier Air Wing Five, the Pacific Command Joint Interagency Coordination Group, and in the Pentagon.

He has served as a Weapons and Tactics Instructor pilot for over fourteen years, in addition to roles as a Safety Officer, Operations Officer, and others; and has accumulated over 3400 flight hours in fleet aircraft.

In 2013, he reported to Naval Strike Air Warfare Center aboard NAS Fallon, NV as the N8 Department Head, leading the Rotary Wing Weapon School, model manager for the Seahawk Weapons and Tactics Instructor course and the Navy Mountain Flying course.

His personal awards include the Defense Meritorious Service Medal, Meritorious Service Medal, the Navy Marine Corps Commendation Medal, Navy Marine Corps Achievement Medal, and others.

Question: What is the mission of rotorcraft aboard the strike carrier?

CDR Weinstock: Historically, the helicopter focused primarily on search-and-rescue missions and, especially during the Cold War, anti-submarine warfare.

Currently, we fly two types of helicopters which continue to play those roles but have an expanded mission set.

Among other missions, they play a major role in the defense of the carrier battle group, dealing with various surface threats, including small boats.

Both helicopter variants, the Sikorsky-built MH-60R and MH-60S, are vital to the overall air wing mission.

The Romeo is especially important in providing radar coverage, both for situational awareness and more explicitly, forward deployed threat detection and target acquisition.

It is focused on sea control.

From off the coast, they can provide outstanding coverage of the sea-base and also look inland; they can see EW signals as well as plot contacts on radar; and push all of that information through a link back to the ship so that the decision-makers on the ship have the latest, most detailed information possible to make well-informed, timely decisions.

The Romeo provides a lot of ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance), that decision-making feed I spoke of.

The Sierras can provide some of that as well, but don’t have a radar.

Both the Romeo and the Sierra have a MTS, a Multi-Spectral Targeting System, which is essentially a FLIR on steroids.

It’s a good system, providing a lot of detail day or night, much better detail than you can get with your eyes at certain ranges.

Working together, one helicopter’s radar tells the battle group where the contacts are that need to be investigated, and the MTS on both helicopter types allow the aircraft to get the definition necessary to know if those contacts are threats or not.

Both assets provide a protective safety net, cooperating with other assets to provide the anti-surface picture, making sure that all the ships remain safe.

The two helicopter types have complementary systems.

The Romeo, with its radar and associated EW (Electronic Warfare) systems, offers situational awareness outside the visual range.

The Sierra lacks a radar, but has a more diverse weapon suite and a very robust self-defense capability.

So I would say that the Romeo is a better battlefield manager, and the Sierra’s going to have more options in dealing with any given threat environment.

Question: Clearly, the ASW threat is a key one, and with the addition of very capable diesel submarines in the global threat environment, the demand signal must be going up?

CDR Weinstock: It is. The Romeo is the only organic ASW (Anti-submarine Warfare) asset in the battlegroup, and is extremely capable.

It has to be; nuclear submarines are becoming more proliferate and the new diesels out there now are definitely not a low-end threat.

Question: The Army has been doing interesting work on linking up RPAs with their helos. The Navy must be working the same challenge and opportunity as well?

CDR Weinstock: We are.

Primarily, the rotary wing UAV, the MQ-8 Firescout, supports missions for NSW (Naval Special Warfare) forces, but has potential functionality in a lot of other mission sets that we are exploring.

The USN as a whole is working through how to best use UAVs in the years ahead.

There are so many missions where they can bring complementary capabilities, or new ones.

We have subject matter experts in my department and others who work on these issues, and we are paying close attention to the opportunities in that arena.

I can clearly see the day when manned assets operating above the water will work closely with UAVs, managing them and sending them forward as needed for coverage.

The UAV’s would greatly expand the battlespace awareness of the strike group, and if necessary, the manned assets could redirect UAVs to areas of greater interest. They could, and probably will, play in other mission sets as well.

Question: Clearly the rotorcraft are not operating alone, so integration with the air wing is a crucial aspect of your operational envelope. What is your approach?

CDR Weinstock: When the air wings come out to NAS Fallon to train with NSAWC, they need to be able to fight as a team.

An integrated, cohesive team.

So the fixed wing assets, both jet and prop, work with the helicopters to accomplish various missions.

For instance, the Romeos work with the Growlers (EA-18G) to locate EW targets and help assess them.

Usually the Romeo is going to be primarily an over-water platform, but it can easily supply information about inland EW systems and threats.

Another example would be CSAR (Combat Search and Rescue), where the Sierras are the primary rescue vehicles for a downed aviator and the air wing assets form a protective umbrella overhead, with strike fighters defending against threats on the ground or in the air, Growlers suppressing missile threats and degrading enemy communications and radar, and the E-2 overhead managing the airspace and providing early warning.

All these different assets are necessary to get the job done, and they all have to train together to be able to accomplish the mission seamlessly when the day comes.

The fixed wing assets and rotary wing assets from the air wings work and train together at other times during a workup cycle, and in other locations, but this is the only place where they can come together to train on an instrumented Navy range.

They brief together, they fly together, they debrief together, and then they do it all again the next day.

Each mission, they get feedback from the various experts here at NSAWC on where to improve.

We have the instrumentation and tools to recreate the missions accurately for highly effective debriefs.

That instrumentation and professional feedback is something that only NSAWC and places like it can provide.

Question: You have instrumented ranges where you can really train to the capabilities, which your “teamed” assets can provide?

CDR Weinstock: Absolutely.

We can create a threat representative environment where F/A-18s, Growlers, E-2’s, and Romeos and Sierras work together in a coordinated manner against a variety of threats.

NSAWC’s range can simulate threat environments ranging from low-end to very high-end.

And by training and operating in these environments, we can practice the tactics we would use in any given theater of operations.

Question: Clearly, the small boat threats are a significant one, notably in operating in high maritime traffic areas. How do you deal with that?

CDR Weinstock: What we are doing right now is training to the specific skill sets needed, all of which apply to that particular mission.

Romeo crews need to be good at battlefield management with their radar and link network, and all of the rotary wing assets need to be proficient at employing ordnance and with their defensive systems and tactics. Defense of the battlegroup against a small boat threat is a mission set where Sierras and Romeos must work together seamlessly.

Here at NSAWC, we can recreate the threat with a collection of vehicles approaching a simulated high-value unit, and the helicopters have to track the targets and practice suppressing the threat.

We often bring F/A-18s and other assets into the problem.

During overwater training, we try and bring P-3s or P-8s into the problem as well by introducing a simultaneous ASW threat.

When we train to a standard where crews can manage multiple threats in a complex battlefield environment, we better ensure we are ready for whatever might happen in theater.

The key point is that we train to integrate the platforms to provide multiple solution sets, complementary sensor and weapon systems, to deal either with an ASW or small boat threat.

It’s incredibly important that we develop those relationships now, as well as the coordination plans, so that we integrate seamlessly on deployment.

Air wing events here at NSAWC are the best opportunity where the crews have the chance to all sit down and brief together, fly together, and debrief together, working out all the kinks and ensuring they are ready for the missions.

Romeos and Sierras are only one part of the overall air wing combat power, but the capabilities they bring are essential to the overall mission.

Battlefield awareness, search and rescue, logistics, anti-surface and submarine warfare, combat search and rescue, and others…

All are important to the overall effort, and all need to be practiced and trained to for proficiency and readiness.

One of the best parts about duty at NSAWC is the chance to work with the other communities – the strike fighters, Growlers, the E-2’s – day in and day out.

No matter what community you’re from, you’re all working towards that same goal, to provide the fleet with the best training in the world.

It makes for a great sense of team-spirit, and makes it easy to go to work every day excited about what you’re doing.

Slideshow

In the first photo of the slideshow above, an MH-60R Sea Hawk from the “Raptors” of Helicopter Maritime Strike Squadron (HSM) 71, embarked aboard the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74), hovers while deploying its sonar dipping buoy during an Under Sea Warfare Exercise involving the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force and the John C. Stennis Carrier Strike Group.

In the second photo, an MH-60S Sea Hawk helicopter from the Golden Falcons of Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC) 12 takes off from the aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN 73). George Washington and its embarked air wing,

In the third photo, a MH-60S Sea Hawk helicopters assigned to the Sea Knights of Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC) 22 approaches the aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman (CVN 75) during a vertical replenishment. Harry S. Truman, flagship for the Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Group.

In the fourth photo, U.S. Navy MH-60S Seahawk helicopter assigned to Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC) 7 flies near the aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman (CVN 75), not pictured, in the Strait of Gibraltar Aug. 3, 2013.

In the fifth photo, a U.S. Navy MH-60S Seahawk helicopter assigned to Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC) 7 delivers cargo aboard the aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman (CVN 75) in the Gulf of Oman Oct. 17, 2013, during a replenishment at sea with the dry cargo and ammunition ship USNS Alan Shepard (T-AKE 3).

In the sixth photo, at PENSACOLA, Fla. (Jan. 14, 2014) Navy search and rescue (SAR) student swimmers ascend up a rescue winch attached to an MH-60S Sea Hawk helicopter assigned to the Dragon Masters Aviation Unit at Naval Surface Warfare Center Panama City Division during a SAR training exercise.

In the seventh photo, Seahawks in support of Bold Alligator 2014, are taking off from a landing area near the Naval Air Station in Norfolk, Va.

Credit photos: USN Media Services for 1-6; the 7th photo is credited to Second Line of Defense.

Background:

From the Sikorsky website:

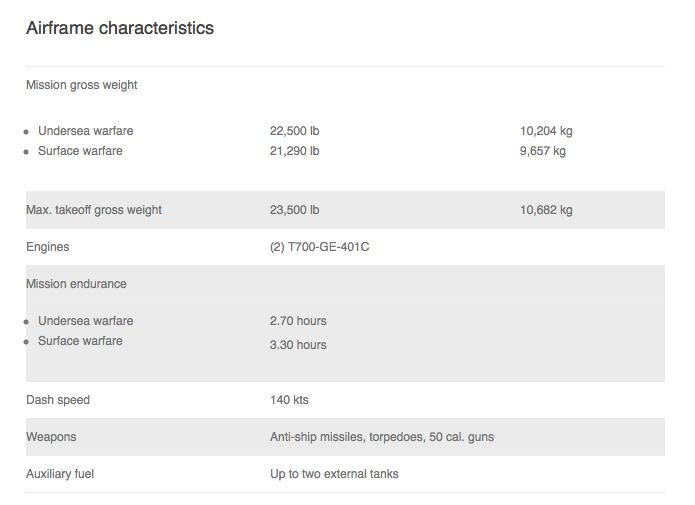

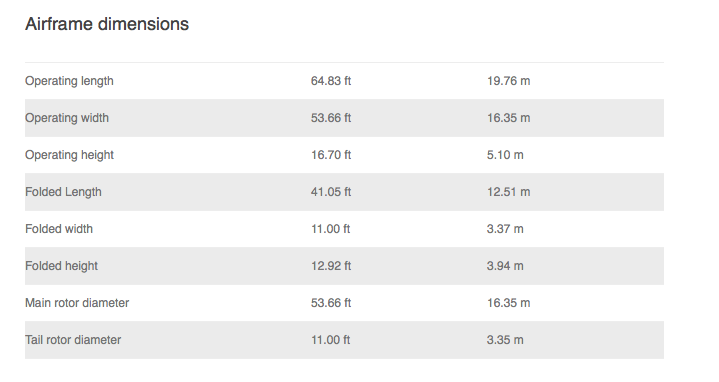

The MH-60R

The MH-60R “Romeo” is the most capable and mature Anti-Submarine (ASW)/Anti-Surface Warfare (ASuW) multi-mission helicopter available in the world today. Together with its sibling, the MH-60S “Sierra,” the SEAHAWK variants have flown more than 650,000 hours across a 500+ aircraft fleet. The MH-60R is deployed globally with the U.S. Navy fleet and a growing number of allied international navies.

The journey from the start of MH-60R flight testing through the first deployment, in 2009, of 11 MH-60R helicopters aboard the USS Stennis, represents 1,900 flight hours, the equivalent of 500 labor years, and a considerable financial commitment by Lockheed Martin.

The MH-60R, manufactured by Sikorsky Aircraft Corp, and equipped with advanced mission systems and sensors by Lockheed Martin Mission Systems and Training (MST), is capable of detecting and prosecuting modern submarines in littoral and open ocean scenarios.

In addition, it is capable of conducting stand-alone or joint anti-surface warfare missions with other Romeo or MH-60S “Sierra” aircraft. Secondary missions include electronic support measures, search and rescue, vertical replenishment, and medical evacuation.

The advanced mission sensor suite developed and integrated by Lockheed Martin includes:

- Multi-mode radar (including Inverse Synthetic Aperture Radar)

- Airborne Low Frequency Dipping Sonar (ALFS) subsystem and sonobuoys

- Electronic Support Measures with an integrated helo threat warning capability

- Forward Looking Infrared Electro-Optical device

- Integrated self defense

- A weapons suite including torpedoes and anti-ship missiles

Lockheed Martin MST also produces the Common Cockpit™ avionics, fielded on both the MH-60R and MH-60S. The 400th Common Cockpit will be installed on the first Royal Australian Navy MH-60R. In 2012, the Common Cockpit exceeded 600,000 flight hours across an operational fleet of 360 aircraft. The digital, all-glass cockpit features four large, flat-panel, multi-function, night-vision-compatible, color displays. The suite processes and manages communications and sensor data streaming into MH-60 multi-mission helicopters, presenting to the crew of three actionable information that significantly reduces workload while increasing situational awareness.

The U.S. Navy is committed to a long-term preplanned product improvement program, also known as P3I, to keep the MH-60R current throughout its life. Recent upgrades have included vital software and mission management systems in the Situational Awareness Technology Insertion (SATI) package as well as design upgrades to the Identification Friend-or-Foe Interrogator Subsystem. Combined with the aircraft’s Automatic Radar Periscope Detection and Discrimination system, the MH-60R’s range of detection will expand — enhancing situational awareness and advanced threat detection — while interference with civil air traffic control systems will diminish.

The MH-60R Electronic Surveillance Measures (ESM) system, which provides aircrew with valuable threat-warning capabilities, has benefited from the installation and maintenance of an ESM autoloader, and the development of Mission Data Loads, which comprise a database of possible threats within a specific region of operations.

Smaller elements are included as well, including the integration of a new multi-function radio called the ARC210 Gen 5 (which sister-aircraft MH-60S will also receive), crucial spare assemblies and integration of other core technologies. The Gen 5 radio will provide MH-60R aircrew with flexible and secure communication.

From the Sikorsky website:

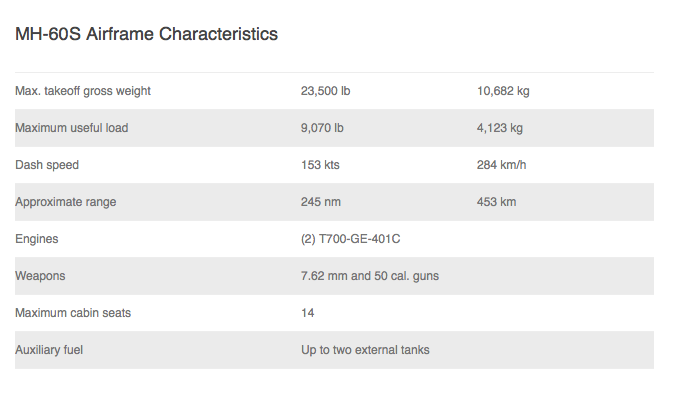

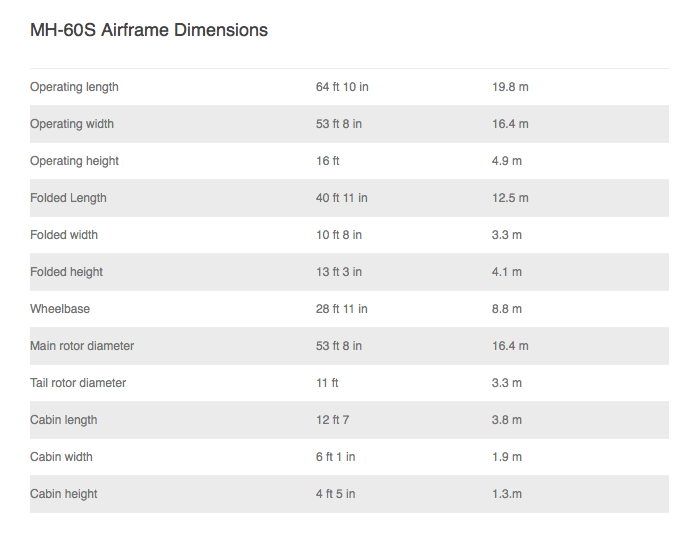

MH-60S Sierra

The MH-60S “Sierra” is the U.S. Navy’s maritime workhorse, and safely and reliably performs missions from vertical replenishment to Medevac.

The MH-60S deploys today in support of modern maritime security missions like earthquake relief in Haiti, and the first deployment aboard the USS Freedom (LCS-1) to conduct regional security and counter-drug operations.

And according to Naval Technology:

The multimission Sikorsky MH-60S Knighthawk helicopter entered service in February 2002. The US Navy is expected to acquire a total of 237 of the MH-60S helicopters, to carry out missions such as vertical replenishment, combat search and rescue, special warfare support and airborne mine countermeasures.

The helicopter began full-rate production in August 2002. As of January 2011 52 MH-60R and 154 MH-60S helicopters were in the service with the US Navy. First deployment of the new helicopter took place on board USS Essex, Wasp Class amphibious assault ship, in January 2003 and a number of MH-60S helicopters were deployed in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

The helicopter was originally designated CH-60S, as a replacement for the US Navy’s Boeing CH-46D Sea Knight heavy-lift helicopters in the vertical replenishment role. The helicopter was redesignated MH-60S as a result of an expansion in mission requirements to include a range of additional combat support capabilities. Retirement of the US Navy Sea Knights concluded in September 2004.

http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/mh_60s/