2015-11-19 By Louis P. Bergeron

In the coming decades, the Bering Strait will emerge as a key global maritime choke point due to its strategic location.

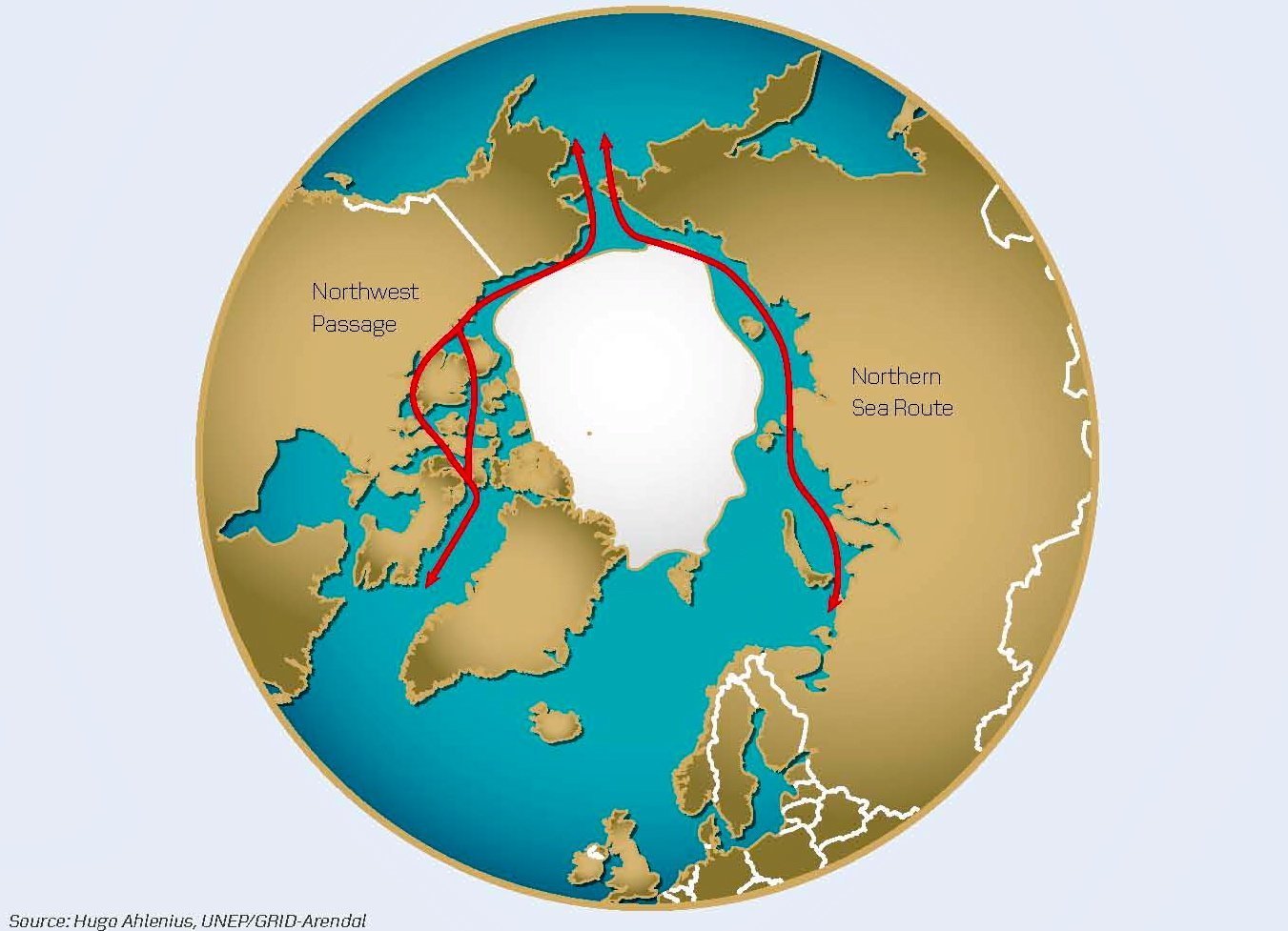

The strait will link the dynamic Pacific Ocean economies with the economies in the North Atlantic Ocean using the increasingly ice-free Arctic Ocean as an economical transit medium, initially via the Northern Sea Route (NSR) over Russia.

The NSR passage saves commercial shippers thousands of miles of transit time and fuel on journeys between East Asia and Northern Europe.

While the savings in energy and time are impressive, the Bering Strait choke point is not without significant risks, both natural and man-made, that will challenge even the most daring businesses.

On the Margins

During the 20th century, most Western students grew up looking at maps centered on the Atlantic Ocean and Europe.

In order to display the world on a flat, two-dimensional surface, the Bering Strait provided cartographers with a logical dividing point to ‘split’ the world. However, this typically put the United States’ state of Alaska on the far left (west) and the Russian Chukchi Peninsula on the far right (east) of the map – seemingly worlds apart.

Yet, this belies the essential closeness of the Eurasian and American landmasses, separated by only the 51 nautical mile, north–south Bering Strait.

The strait’s depth of 30 to 50 meters connects the Arctic Ocean’s Chukchi Sea and the Pacific Ocean’s Bering Sea – representing the sole sea line of communication (SLOC) between these two oceans.

The divide, while relatively short distance-wise, represents a large temporal divide with the International Date Line traversing the center of the strait: the Russian side is 21 hours ahead of the Alaskan side. In the depths of winter, ice flows occasionally clog the span of the strait from November to May, yet strong currents usually prevent a total freeze-over.

In the middle of the strait, the two Diomede Islands – Russia’s Big Diomede to the west and the United States’ Little Diomede, have stood witness to the thaws and freezes of the Bering Strait just like the relationship between the United States and Russia with only 2.4 miles separating the Cold War adversaries’ respective islands.

The Bering Strait has a long history of being a connector.

It connected Asia to the Americas via Beringia, also known as the Bering Land Bridge, during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Indeed, many credit Beringia for enabling the first major human migration from Asia into the Americas some 20,000-30,000 years ago. The connection, however, did not last, and as the glaciers receded, the land bridge re treated under the icy waters around 11,000 years ago as the Arctic Ocean and Pacific Ocean joined together at the Bering Strait.

The Bering Strait became known to Europeans in 1648 when Russian explorer Semyon Dezhnev reached the strait and discovered a native population living in the harsh conditions. In 1728, Virus Bering, a Danish navigator, took a Russian expedition to the strait. This expedition gave names to both the strait and the Diomede Islands – named in honor of the Russian Orthodox St. Diomede.

The entire area, claimed by Russia with competing claims by Britain and Spain, was largely neglected by the non-native population for another century. In 1867, in the midst of the post-US Civil War reconstruction era, US President Andrew Johnson’s Secretary of State, William Seward, negotiated a US$7.2 million (US$120 million in 2015 currency) payment to the Russian Empire for purchasing Alaska. Largely derided at the time by Johnson’s opponents as “Seward’s Folly” and “Seward’s Icebox,” perceptions of the purchase changed during the Nome Gold Rush in the late 1890s, which drew thousands of prospectors to the shores of the Bering Strait for the opportunity to strike it rich, including famed Wild West lawman Wyatt Earp who operated a saloon in Nome during the height of the rush.

During World War II, the Bering Strait became a crucial artery for the Lend-Lease Program goods travelling by sea and air over Alaska from the United States to the Soviet Union. The Bering Sea route was a much safer transport route when compared with the vulnerable convoys on the North Atlantic Ocean. Imperial Japan, in an= attempt to distract the Americans from actions in the South and Central Pacific, captured several of the United States’ Aleutian archipelago islands in the northern Pacific Bering Sea area.

Japan’s military actions spurred a massive US infrastructure investment in Alaska to back the Aleutian Islands. The World War II investment enabled significant development in Alaska in the post-war era.

For instance, US exploitation of the rich oil resources on the Alaskan Northern Slope in the 1970s owed much to World War II investments in Alaska. The Cold War presented the United States and then Soviet Union military with incentives to fortify their respective sides of the strait. The icy, four-decade standoff across the strait hid the sometimes very hot conflict happening under the seas of the Pacific and Arctic Oceans.

The Bering Strait served as a key transit corridor for conventional and nuclear-powered attack and ballistic missile submarines whose presence under the ice or in the frigid waters of the Arctic Ocean sometimes provided opportunities for intelligence collection and remains the quickest route for delivering a nuclear strike via submarine-launched or strategic bomber-launched weapons.

No longer on the margins New world maps showing up in classrooms and offices have started reflecting the changing global economic and power dynamics by placing the Pacific Ocean in the center of the map instead of the Atlantic.

This spatial reordering makes the Bering Strait a prominent feature at the top center of the map. With the strait no longer at the left and right edges of the map, one clearly sees the geostrategic importance of the Bering Strait as a connector and a divider.

In the thaw from the Cold War, it seemed that the Bering Strait might symbolize a lessening of tensions between the United States and Russia; a Bering Strait tunnel was even discussed by ambitious developers to link together the two countries, reuniting Asia and the Americas after thousands of years of separation.

However, the geopolitics of the strait and the Arctic have turned frosty again since Russia’s involvement in Ukraine and now in Syria; the Bering Strait again has a front row seat to a declining Great Power relationship between the United States and Russia.

At a macro level, climate change is changing the dynamic in the Arctic Ocean, affecting the geostrategic importance. No place on earth has seen such rapid increases in temperature and alteration of climate as the Arctic. As the light-colored, reflective surface ice melts, the darker, now exposed seawater absorbs more solar radiation, making it warmer.

This warmer seawater then melts more of the surrounding ice in a vicious feedback loop contributing to the rapid decrease of Arctic sea ice.

The emerging consensus among climate scientists and climate models predicts that by the 2030s the Arctic will experience an ice-free summer, meaning there will be no significant ice packs left in the Arctic Ocean by late summer.

Some predictions even state that by later in the 21st century or early next century, given current trends, the possibility exists for a nearly year-round ice-free Arctic Ocean. Regardless of the exact dates, the fact remains that the indigenous human, animal, and marine ecosystems of the Arctic face radical, lasting changes in the coming decades.

With the reduced sea ice, the Arctic’s untapped resources and favorable geography becomes more attractive.

By some estimates, 10% of the world’s ‘discovered’ and 25% of the world’s ‘undiscovered’ conventional oil and gas lies underneath the Arctic Ocean for exploration and exploitation. Methane hydrates, frozen gas crystals found on the cold Arctic Ocean floor, might also entice energy companies and countries looking for cleaner-burning fuels in the future.

Additionally, fish stocks might become available to fishermen coming through the Bering Strait to capture fish that take advantage of the increasingly warmer waters of the Arctic Ocean. Tourism also stands to increase as the sea ice recedes.

Maritime traffic is poised to rise as well. The former Commandant of the US Coast Guard, Admiral Robert Papp, testified to the US Senate in March 2015 that: “The Arctic Ocean is becoming more navigable as evidenced by an increase in shipping through the Northern Sea Route over Russia.

We have also seen an increase in shipping through the Bering Strait, a potential future choke point for trans-Arctic shipping traffic.” The US Coast Guard (USCG) reported a 118% growth in Bering Strait transit traffic from 2008 (220 transits) to 2012 (480). In 2009, two German merchant ships demonstrated the advantages of using the Bering Strait by sailing via the Russian Northern Sea Route from Vladivostok to Holland without the assistance of an icebreaker, shaving an impressive 4,000 nautical miles off of a regular 11,000 nautical mile transit.

Subsequent transits have captured the attention of shipping companies who grasp the significance of avoiding the pirate-prone, congested maritime choke points at the Straits of Malacca and Bab el Mandeb, as well as the restrictive transit through the Suez Canal.

The China Ocean Shipping Company, COSCO, remains publicly optimistic about the NSR. It recently sent a COSCO cargo vessel to Sweden from China via the Bering Strait and NSR in August 2015; the vessel will return to China through the NSR in October 2015 before the ice cap expands south in November restricting free, unescorted transits.

Management and Strategies

Generally, since the end of the Cold War, the Arctic has been a region of mutual interest and co-operation. The chief co-operation element for Arctic policy is the Arctic Council. Founded in 1989, Canada, Demark (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States constitute the council. The United States assumed two-year chairmanship of the rotating chair in April 2015.

Of the members, most are North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies with the exception of Russia, Sweden, and Finland. In addition, 12 observer countries to the council include China, Japan, South Korea, Germany, and the UK: countries without physical Arctic equities, but with interests in the environmental energy, and transit opportunities that the Arctic provides. The council has succeeded in securing agreements on protecting native peoples, the environment, and resolving maritime boundary disputes as they arise.

Additionally, the USCG announced on 30 October 2015 the Arctic Coast Guard Forum to address some of the issues described above through regional co-operation, with the forum including all of the Arctic Council members, even Russia.

To highlight the growing importance of the Arctic region, US President Barack Obama visited the Arctic Circle in August-September 2015, the first sitting American President to do so. His administration has attempted to demonstrate American commitment as an ‘Arctic Nation’. The Obama administration inked a US Arctic Strategy for public release in March 2013. This national strategy was quickly followed by a USCG Arctic Strategy (May 2013), a Department of Defense Arctic Strategy (November 2013), and an updated US Navy Arctic Roadmap (February2014).

All of these Executive Branch documents served to put forth a US narrative of the long-term prospects and challenges of a warming Arctic. Each document discussed securing the Arctic environment, native populations, and responsibly enabling exploration and possible extraction of natural resources.

Additionally, the US military and Coast Guard clearly want to ensure access to the Arctic Ocean as an area of military operations and for disaster response, search and rescue, and scientific expeditions, as well as using the Arctic as an arena of international co-operation with allies, partners, and competitors (e.g. China and Russia).

Understandably, the Russians have also included the Arctic and the Bering Strait as a key part of their national security and economic strategy. President Vladimir Putin’s narrative of a resurgent Russia includes a new, muscular naval doctrine unveiled in July 2015 that looks to the Arctic as an area of Russian military strength as the vital corridor to link the Russian Atlantic and Pacific Ocean fleets.

Plus, a review of NSR transits provided by the Northern Sea Route Information Office shows that 31 vessels made a complete NSR transit in 2014 from Cape Deshnev at the Bering Strait west to the Barents Sea, and from the Barents Sea east to Cape Deshnev and through the Bering Strait.

Most of the Russian-flagged vessels were general cargo and petrochemical carriers, and transits took place from late June to early November, ranging in length from 5 days to 43 days. Of those 31 vessels in 2014, however, only six were not Russian-flagged, showing use of the NSR is still overwhelmingly Russian de spite the successful cargo transits mentioned previously.

The Future Challenge

While signs point to the Bering Strait growing in importance for international commerce, energy, and environment, significant challenges remain.

For starters, the volume of traffic through the Bering Strait when compared to the world’s major maritime choke points shows a relative scale mismatch. The Strait of Malacca, for instance, has over 70,000 vessel transits annually, compared to the 480 through the Bering Strait in 2012.

It is simply easier under the current conditions to ship via the traditional maritime routes through the Indian Ocean.

The energy development long sought by global oil and gas companies has largely failed to materialize for several reasons.

One reason is the logistical challenge of operating above the Arctic Circle: ice or no ice, harsh weather prevails so resupply is difficult. Most oil companies had to use Seattle as their base of operations for their large exploration platforms before taking them through the Bering Strait.

Energy companies became nervous after the BP Deepwater Horizon oil platform tragedy in the Gulf of Mexico because of the herculean efforts required to cap the oil well, which would be impossible in the rough conditions of the Arctic so far from any significant maritime logistics resources.

In September 2015, Royal Dutch Shell, an international energy giant, announced that it had suspended oil and gas exploration efforts in the Chukchi Basin north of the Bering Strait “for the foreseeable future” after spending billions of dollars for the drilling block license and on the exploration operations.

The decline in global oil prices, as well as the potential for spills and negative media associated with the possible environmental sensitivities forced Shell’s hand after years of preparation. After Shell’s exit, the Obama administration’s Interior Department suspended the next round of oil and gas block lease sales in the Arctic for 2016 and 2017. Interior’s next lease period is expected for the 2017-2022 five-year leasing plan proposal, but leasing during that timeframe might also be cancelled.

While these recent developments do not spell the end of Arctic oil and gas exploration and exploitation in the long term, in the near-term, market winds have stopped the Arctic hydrocarbon rush cold.

Before the Bering Strait can serve as a vital maritime choke point, the United States and Russia need to develop port facilities for refueling, repairs, and emergency response. Nome on the American side, home to 9,000 persons, is the largest populace in the strait. A March 2013 US Army Corps of Engineers “Alaska Deep-Draft Arctic Port System Study” found the navigation channel at Nome presently ranges from 3-6 meters in depth. The US harbor at Port Clarence has a natural depth of 10-12 meters, but with few people and even fewer services.

On the Russian side, Provideniya and Chukotsky have 4,500 and 5,200 inhabitants respectively. In order for the strait to attract more shipping commerce, a deep-draft Arctic port will need to exist.

Perhaps, in the future, Nome or Port Clarence might become the ‘Singapore’ of the Bering Strait – an area for interconnected transfer and receipt of cargo. That day, however, might be several decades away.

In the meantime, maritime safety remains the chief concern in the region – both environmental response and search-and-rescue (SAR) assets are few and very far in between. The USCG maintains the most robust capability in the region with their District 17 vessels, aircraft, and helicopters, yet the tyranny of distances and the generally poor operating conditions due to weather, affect their ability to respond to crises.

Maritime safety thus becomes a critical issue because of limited response capabilities; tracking vessels becomes more important in the area and this requires increased maritime domain awareness (MDA) in the region. Extensive use of Automated Identification System (AIS) is necessary for search-and-rescue missions, environmental concerns, tracking tourists, fishing fleets, and overall maritime traffic, especially in the tight confines of the Bering Strait.

In 2009, the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) approved revised “Guidelines for ships operating in polar waters”, which codified ship construction, environmental, and operating standards.

These standards, while welcome, also might serve to discourage commercial shipping companies from using the Bering Strait and NSR due to the costs associated with meeting the MSC guidelines with their current fleet of vessels.

Lack of icebreakers for the United States also hampers development. The United States has only two operational icebreakers, one medium icebreaker and one heavy, with one other heavy icebreaker undergoing serious repairs.

Meanwhile, Russia boasts over 40 icebreakers, including nuclear-powered icebreakers, to assist with keeping the Northern Sea Route open for most of the year, and to shepherd Russian naval vessels from east to west and west to east. In a July 2015 release, Russia’s new naval doctrine says that it will make investments in a new fleet of icebreakers to ensure Russian fleet use of the NSR year-round.

During President Obama’s Alaska visit in September, he called on Congress to fund a new icebreaker to start construction in 2020 instead of the current budget’s 2022 commencement.

From a military perspective, the Bering Strait and Bering Sea will likely be an area of contention. The strait remains a vulnerable choke point for the Russian Navy, especially if it is surging naval forces to the Pacific or from the Pacific to the Atlantic.

Additionally, other observer nations have expressed interest in operating in the region. When President Obama was in Alaska, China’s People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLA-N) sailed several warships into the Bering Sea around the Aleutian Islands.

The US military runs into authorities issues in and around the Bering Strait as it serves as an overlapping area of interest for three geographic combatant commands: Pacific Command, Northern Command, and European Command, and a functional Combatant Command: Strategic Command, which monitors for ballistic missiles entering US airspace over the Arctic.

While armed conflict in the Bering Strait is a very remote possibility, as militaries start to operate there more frequently and development, commerce, and resources are unlocked, the risk of miscalculation grows.

Development and establishment of the Bering Strait as a critical maritime choke point and sea line of communication will take decades, and the extreme challenges of operating in that Arctic environment for energy exploration, tourism, fishing, and commercial shipping will persist.

Yet, the strait has a long history of being a connector, connecting Asia to the Americas and connecting the Arctic Ocean to the vastness of the Pacific and Indian Oceans. As the world looks to a Pacific Ocean-oriented 21st century, the

Bering Strait will no longer occupy the margins.

This article is republished with permission of our partner Risk Intelligence.

The latest issue of Strategic Insights (No. 60, November 2015) focuses on key strategic choke points globally and is a must read for addressing this critical geopolitical dynamic.

http://www.riskintelligence.eu/maritime/strategic_insights/

For some earlier pieces on the Arctic published on Second Line of Defense see the following:

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/denmark-holds-arctic-emergency-exercise/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/coast-guard-cutter-healy-arctic-cruise-2015/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/is-the-us-ready-for-sustained-arctic-operations/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/arctic-challenge-exercise-2015-ends/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/arctic-challenge-exercise-2015-norway-as-the-lead-nation/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/special-report-june-2014-european-defense-the-arctic-and-the-future/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/admiral-wang-on-baltic-and-arctic-defense-a-danish-perspective/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/shaping-arctic-defense-leveraging-the-grid/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/the-arctic-opening-co-opetition-in-the-high-north/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/sarex-13-and-the-arctic-challenge/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/russian-resurgence-and-the-arctic/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/greenland-and-the-arctic-the-emergence-of-a-new-sovereign-state/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/preparing-for-an-arctic-future-general-jacoby-looks-at-the-challenges/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/how-ready-is-the-us-navy-for-arctic-operations-not-very/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/alaska-the-arctic-and-crafting-strategic-depth/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/china-and-the-arctic-an-element-of-an-evolving-global-strategy/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/the-why-for-the-norwegian-f-35-decision-the-arctic-dimension/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/a-danish-perspective-on-the-challenge-of-arctic-security/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/ending-reluctance/

The slideshow above highlights the USCG Cutter Healy’s Arctic Cruise 2015.

- In the second photo, a conductivity temperature depth monitor is lowered into the Arctic Ocean from the Coast Guard Cutter Healy July 10, 2015. The CTD monitor will test the water for oxygen levels and salinity.

- In the third photo, a small-boat crew from the Coast Guard Cutter Healy works with scientists to place a device called a wave rider into Arctic waters for testing, July 11, 2015. The Healy is conducting operations in the Arctic with the Coast Guard Research and Development Center and scientists from various other agencies.

- In the fourth photo, National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration scientist Kevin Vollbrecht launches a Puma unmanned aerial vehicle from the bow of the Coast Guard Cutter Healy July 11, 2015. The Puma is being tested for flight and search and rescue capabilities.

- In the final photo, Coast Guard Cutter Healy crewmembers move a 1,000 pound buoy into place for deployment in the Arctic, July 10, 2015. The buoy also has a clump anchor, which will keep it in place until it is recovered.

Credit:U.S. Coast Guard District 17 PADET Anchorage:7/10/15