By Robbin Laird, Ed Timperlake and Murielle Delaporte

U.S. Navy’s Military Sealift Command (MSC) stands as the base of the Navy sea pyramid, providing the foundation and services that enable the warfighting ship to operate at and from the sea.

Yet when it comes to the struggle for resources, the services compete for assets and resources which reduce the focus upon the logistical enablers for global operations.

One key enabler, commercial mariners, who are always at sea and do not rotate to shore billets like active duty Sailors, are not visible in the Pentagon’s budget battles.

As the Navy develops and refines the concept of distributed lethality, there is increasing awareness that combat logistics will play a key role if this concept is to become reality.

Not only does the fleet need to operate over greater distances to supply a core combat group, but speed and sustained logistics becomes more important in supporting a fleet, which may well wish to distribute rapidly in times of crisis.

With the coming and in-process retirement of the current generation of mariners, experience gaps are a potential vulnerability.

And the significant decline in the size of the U.S. flag merchant marine fleet engaged in the international trade (less than 80 currently) and the requisite decline in the pool of trained mariners poses a significant strategic challenge looking forward.

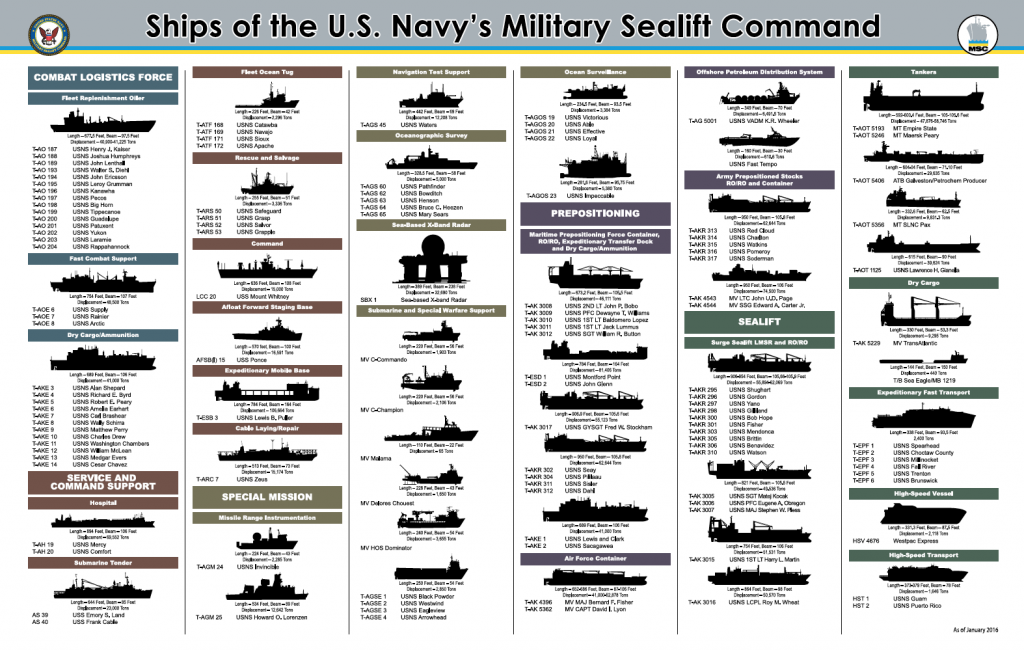

MSC is receiving or has received new ships, such as 12 Dry Cargo & Ammunition ships (T-AKE), 10 Expeditionary Fast Transports (T-EPF), previously known as the Joint High-Speed Vessels (JHSV), two Expeditionary Transfer Docks (T-ESD) and the Expeditionary Mobile Base (T-ESB) which is the sea base variant of the ESD.

However, recapitalization remains a work in progress, as with the need to shape a new tanker fleet, and fund supply ships to support the carrier force which senior U.S. Navy Admirals are envisaging.

Without the logistics support, the deployed spider web strike force is not going to go very far.

And some of the new ships have their own challenges, such as the Expeditionary Fast Transport, which requires specialized training for the mariners.

This certainly is true for the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), a ship which does not want to operate very far from ports because it needs constant or what the Navy has called “distance support” and also has significant limitations in extremely rough seas.

The LCS, which has been designed with limited combat capability from the ground up, adds additional complexity to the logistics fleet and its global requirements towards servicing a more distributed fleet.

As the then commander of MSC, Rear Adm. Mark Buzby put it in an interview with us:

SLD: Speaking of the LCS, and the question of the demand side posed by deployed LCSs, how will they impact your workload?

It probably depends on how the LCS is deployed, because if it is dispersed that would be challenging for the MSC fleet.

Admiral Buzby: It’s going to make us very busy. We’re busy now; it’s going to make us even busier.

And those particular ships have one refueling station, and they have no connected replenishment, so the only way they can get their supplies at sea is via vertical replenishment on the flight deck.

In mid-December, after visiting the dry cargo & ammunition ship USNS William McLean (T-AKE 12) and the fleet replenishment oiler USNS Kanawha (T-AO 196), we had a chance to talk with Rear Adm. T. K. Shannon, MSC commander, and his staff about the way ahead for MSC in a period of change for the sea services.

Question: Let us start with the major challenges which MSC faces; what would you identify as the most significant challenge?

Admiral Shannon: One thing I wake every morning thinking about is if the President declares the need for the country to go to war, how will the logistical side of the military meet the challenge?

This is a challenge for airlift, land transportation, and for us, of course, sealift.

And a major structural challenge we face is the decline of the U.S. merchant marine.

It is clear and it is a challenge; for we recruit our mariners from the U.S. merchant marine.

The Jones Act and the Maritime Security Program are important but not enough.

We need things like more cargo preference to ensure that we have adequate U.S. merchant shipping.

I know some people consider cargo preference corporate welfare.

I consider cargo preference an investment in our national security because if you put some cargo on the table, the U.S. flag will see an opportunity and they will acquire or build U.S. flag ships.

They will flag them in the United States if there’s some cargo there for them to haul.

Question: So from the MSC perspective, one could look at cargo preference as a proactive incentive, which supports the logistical side of sea service operations?

Admiral Shannon: That is a fair way to put it.

With such an approach, we can build capacity in the merchant marine and, in turn, expand the base of mariners available to us in time of need.

Those mariners are critical to us because when you look at today’s MSC report, we have 61 ships in a reduced operating status.

Forty-six of those are over at the Maritime Administration and 15 of them are with Military Sealift Command.

And they’re mostly large roll-on/roll-off vessels and dry cargo vessels; and they’re strategically dispersed around the country with 10 to12 mariners on each ship.

When the president rings the bell, we go to the union halls and we man the ships up to whatever their manning requirement is.

It’s typically about another 20 persons per vessel.

So, right there, 60 times 20, we need 1,200 mariners to fall in from somewhere, and where they’re going to fall in from is the U.S. flagged merchant fleet.

The capacity of a robust U.S. flag merchant marine and its manpower is the engine which enables us to carry our country to war when ordered.

Question: Are we reaching a critical threshold on shortfall?

Admiral Shannon: We are getting awfully close.

Three decades ago, when I came into the U.S. Navy, we had around 400 ships in the merchant marine.

Today that number is down to 77 in the international trade.

Just a few months ago, that number was around 80.

That is a drop from the beginning of 2015.

We are getting close to that magic number where we clearly will not have enough U.S. flagged merchant ships to generate the mariners, which MSC will need to operate, notably when we mobilize.

And it is not just a question of mariners; it is about the shipbuilding base and ship repair facilities being available in the United States.

And when one folds-in anticipated war damage in conflict, the question of repair capabilities is clearly of central significance.

Question: When considering global conflict, the challenge will be to protect the convoys so to speak and to ensure continuous flow of support as well.

What are concerns with regard to this challenge?

Admiral Shannon: Let us take the case of our support to Iraqi Freedom.

For example, on a single day in 2003, 167 ships under the cognizance of Military Sealift Command were moving cargo to support the operation in the Middle East. Because the sea was uncontested, this was relatively a walk in the park.

Fast-forward to today’s Pacific, where there clearly are powers capable of contesting us at sea.

How then do we do the logistical support necessary for the operation of the sea services operating forward in a contested environment?

Question: It is clear what you are discussing is the surge side of a conflict and suggesting that we are getting to a critical point.

Do you have reserve officers who might be mobilized?

Admiral Shannon: We do have a pool of reserve officers and they’re in a specialty called the Strategic Sealift Officer program.

It is a limited number, but does exist.

Question: What about the allied demand and support side of the equation?

When we met with the Captain of the USNS William McLean, he discussed the absence of tankers for the Canadian Navy and his role in tanking various allied ships in a North Atlantic exercise.

What about the reverse, namely, working relationships with allies which provide support to the U.S. sea services and allies as well?

Admiral Shannon: We have a formal relationship, namely with the British and their Royal Fleet Auxiliary. We do annual staff talks with them and our ships can fall in seamlessly with their logistic ships.

We meet regularly but need to do this in the Pacific as well, with Japan, Australia and India, for example.

We enjoy great relationships with those countries, but I need to increase it to yet another level.

We need to formalize some of our agreements and looking at it together with our allies to make sure we are truly interoperable.

Question: The sea services are undergoing a fundamental change in focus, which is summarized by shaping a sea base approach, which is really about the ability to project the tip of the spear and to link back to air and sea capabilities to extend the lethality and effect of the sea base.

Obviously, there is a logistical side to this, and the challenge is to have the networks and integration to work in an integrated manner with operational sea basing.

How would you describe the challenge and the way ahead?

Admiral Shannon: We are clearly working the approach.

How would we task organize logistical support to a deploying sea base?

How do we work the command and control, the security and the operational connections?

Sea basing in a contested environment clearly sets demands as well for the kind of logistical support, which will enable combat effectiveness.

Importantly, MSC operates ships that are a part of the seabasing construct including the expeditionary fast transports, expeditionary transfer docks, prepositioning ships, dry/cargo and ammunitions ships and our large, medium-speed roll-on/roll-off vessels.

Question: It is clear that this challenge entails a partnership and allied rework of the operating relationships so that the reach of the sea services can be supported and extended with those of our allies and partners.

What is your sense of this challenge?

Admiral Shannon: I think that is a key part of the way ahead.

We will not solve the ability to operate in a contested battlespace with our fleet assets alone; we need to work with allies and partners from the ground up on an evolving approach.

Question: MSC has under its jurisdiction a wide range of mission ships.

From one point of view, this clearly is challenging as a command.

From another point of view, it can drive innovation.

How does the variety of missions and vessels drive innovation?

Admiral Shannon: One key driver is our close relationship with various parts of the private or commercial sector.

We are never far from a new idea about how to work more effectively.

We are not dependent on the bureaucracy to provide for sponsored innovation.

To a certain extent MSC operates like a commercial business which is very different from the rest of the Navy.

Having our own engineering and contracting authority enables us to seek efficiencies and look for innovative ways to improve the services provides to our customers.

This is the third piece generated from our visit to the Military Sealift Command in Norfolk on December 14, 2015.

A Very Capable Multi-Mission Support Ship in the MSC Fleet: Demand Drives Operational Diversity for the T-AKE Ship

01/19/2016 – The USNS William McLean is one of the 14 T-AKE supply ships operating in the Military Sealift Command.

Given the shortage of ships for the USCG and the US Navy, the ship has been tasked to do a diversity of missions far beyond simple fleet replenishment.

As both Captain Phillips and the crew of a sinking sailboat off of the East Coast of the United States were to discover. …

Military Sealift Command’s Tanker Fleet: Sea Services Con-Ops Drives Up Demand

01/20/2016 – The Military Sealift Command fleet is being modernized but is facing the challenge of supporting the evolving concepts of operations of the US fleet as it moves toward distributed operations worldwide.

https://sldinfo.com/military-sealift-commands-tanker-fleet-sea-services-con-ops-drives-up-demand/