2016-11-05 By Robbin Laird

© 2016 FrontLine Defence (Vol 13, No 5)

During a recent visit to Australia to participate in the Williams Seminar on air-land sea integration, I had the chance to visit with DCNS Australia and get their perspective on the way ahead in building a new class of submarines. I was able as well to discuss with senior Royal Navy officers how they view this new way forward, and will discuss that in later articles.

In mid-August 2016, I sat down with Brent Clark, Director of Strategy at DCNS Australia. An experienced submariner with the Royal Australian Navy, he wanted to continue to work on naval systems after retiring from the RAN. He found opportunities in the private sector, including at Thales Naval Systems in Australia. When DCNS Australia was created in early 2015, Clark joined the company to help guide the competitive bid, which won Australia’s submarine contract earlier this year.

We started by discussing why he believed that DCNS won the competition. He emphasized that French domain knowledge in the submarine business and operations as well as the French commitment to sovereignty in the area had an important impact on Australian thinking. Clearly, the Aussies wanted a submarine that operates throughout the Pacific and one their own industry could build and support in a sovereign manner.

“There are actually only two countries in the West who still understand what sovereignty is and requires in the development and manufacture of military platforms – the United States and France. If Australia wants to learn what sovereignty in this area means, they clearly have to work with a nation that does know, and exercises such capabilities.”

Given that the United States does not build diesel submarines, the only other real candidate in Clark’s view was France, and hence DCNS. The competition was among three contenders: Japanese, German and French. Of these, only the French company, DCNS, had the kind of long-standing experience in operating a submarine at the distances that Australia wanted.

“The French had been operating submarines in a very tactical, fully-deployed way for a very long period of time, which is in clear contrast to either Japan or Germany currently. France deploys its submarines into the Western Indian Ocean and operates on long deployments similar to Australia or the United States. In contrast, Germany and Japan operate their submarines at sea for about a month at a time. And being able to support and sustain longer deployments is crucial to Australia for its next generation submarine as well.”

We went on to discuss the impact of the Collins-class experience on how Australia is considering its next generation submarine. Clark underscored that Collins was a one-off variant of a Swedish submarine and, as such, meant that Australia had to operate in a sui generis space with regard to the evolution of these submarines.

“We had a Swedish exchange officer come to sea with us when I was onboard a Collins-class submarine and we deployed to New Zealand,” noted Clark in explaining this. “On Day-28 of the deployment he walked into the wardroom and stated that ‘I’ve now set a record as a Swedish submariner for the most continuous days at sea.’ We all looked at him and thought “we’re only at sea for 28.”

Clark contrasted the experience with the Oberon-class submarine, which preceded the Collins, in that there were 19 different countries using Oberon-class submarines, which constituted a comprehensive user group. This meant that Australia could leverage other nation’s operational experiences.

“With Collins, we ended up operating six boats by ourselves with very little reach back to Sweden because they didn’t operate the same way, and they hadn’t operated that submarine either. So it took Australia an awful long time to realize what that means.”

Clearly Australia does not want to pursue a sui generis program with a country that does not have extensive long distance operating experience. The DCNS offering allows Australia to draw upon French operational experience and evolving technologies, to be part of a larger submarine enterprise, and, with the combat systems being American, being able to leverage U.S. combat systems technology.

In other words, much like the rest of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) which is moving towards buying platforms where they are part of global fleets or systems, the Navy wanted to ensure that they did the same with regard to their new submarine class. And DCNS brings to the Australian Navy significant experience with regard to cooperative building and sustaining of submarines in the manner in which Australia will want to operate in the extended battlespace.

“We were very confident of the operating cycle of the submarine. We’re very confident of the maintenance of the submarine, and the maintenance philosophy. The French maintain their sovereignty exactly in the same sort of cycle that the Australians wanted.”

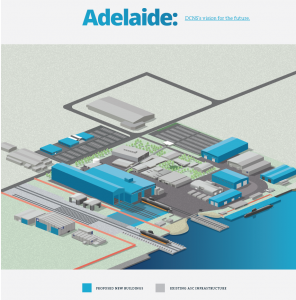

We then discussed the track record of DCNS in transferring the kind of technology Australia wants to build the new generation submarine, and particularly the ability to leverage what Australia has already invested in the infrastructure at Adelaide.

“The company is very good at transferring technology, which was a requirement for Australia,” noted Clark. “The Brazilian example was important for Australia as, in that case, DCNS provided the Brazilians with the ability to create a sovereign production capability for their Scorpion-class submarines. You don’t have to go back to France for anything if you don’t wish to.”

DCNS will be working with Australia to ensure a 21st century infrastructure for the build and the sustainment of the submarine. Clark also explained that DCNS builds submarines differently than do the Japanese and Germans.

“We vertically integrate sections as opposed to horizontally integrate them for a whole range reasons, including occupational health and safety. Having worked in a variety of shipyards, one of the big problems you have is lots and lots and lots and lots of eye injuries from dust and rubbish going to people’s eyes. That’s because welders end up welding on their back. The way we build is basically the welders stand up. So that’s it. It is more efficient and more productive.”

Reportedly, stealth, or the lack of it, also contributed to choosing the French Barracuda, but such details are classified.

A key part of the program is to shape a new way to build ships in Australia, which will almost certainly happen with the new air warfare destroyer as well.

The design contract between DCNS and Australia was signed on September 30th, and Australian technicians will move to Cherbourg and start the process of preparing for the technology transfer necessary to build the new submarine in Australia. Over time, the French manpower involvement in the program will decrease as the Australians ramp up their manpower numbers in the submarine build process. “Where the requirement for French supervision starts to end really depends on how quickly we can get the Australian workforce skilled, and productive,” noted Clark.

In late September, Lockheed Martin Australia was selected by the Australian government as the Combat Systems Integrator (CSI) for the submarine program, and DCNS Australia will work closely with them also.

“We have said the three entities – DCNS, the CSI and the Commonwealth – must work together to deliver a whole warship performance. We are going to co-contract with the CSI for performance.”

This evolving and integrated approach is also in contrast with the Collins class experience. “If we go back to the combat system on Collins which was basically supplied as government-furnished equipment (GFE) – the builder had no ability to interact – boxes would turn up and the builder was told to install them. The builder did that, but of course when the combat system was turned on, it didn’t work properly.”

These lessons have contributed to the DCNS message and way of doing business explained Clark. “We consistently and constantly said during the competitive evaluation process that we could not work any other way but collaboratively with the CSI – and that clearly is the way ahead for a successful program.”

http://defence.frontline.online/article/2016/5/5503-Industry-Perspective-on-New-Aussie-Subs

The slideshow highlights the Collins submarine and the photos are credited to the Australian Ministry of Defence.