2017-05-05 By Robbin Laird

The Williams Foundation seminars on the crafting and empowering of an integrated force has focused largely on key elements for reshaping the force and enabling the capability to shape a more effective and integrated combat force.

This will simply not occur without a significant reworking of the partnership with industry and the capability to bringing outside players in shaping innovation inside the process of defining, designing and building the force over time.

The process requires a much greater degree of openness to the inclusion of industry in shaping capabilities.

In an article about Plan Jericho and the new approach towards industry, a way ahead was highlighted.

With the backing of RAAF leadership, the team decided to apply this new approach to the challenge of retrofitting the Hawk 127 Lead-in-fighter jet with the technology needed for it to operate under a new airspace management system in Australia. OneSKY requires all civilian and military aircraft to be fitted with an automatic dependent surveillance broadcast (ADS-B) system that digitally shares their precise location.

It will be significant investment in time and money to have ADS-B on all military aircraft.

But the Hawk 127 posed a problem. “There’s very little real estate in which to put anything and the plane’s original manufacturer told us the solution was going to be very costly and take considerable time to develop,” Wing Commander Reid says.

“So we partnered with BAE Australia and invited all the aerospace sector players – some 20-odd players, including the primes such as Airbus, Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon as well as small Australian players such as Enigma Aviation – into the Design Innovation Research Center. There were over 40 people there from around the world, and we locked them in a room and said, ‘Let’s understand the complexities and then solve this problem.”

There was a lot of resistance initially as the DIRC team pushed the group outside their comfort zone of a traditional engineering approach, Professor Bucolo says.

“One of the really crucial things we did was we brought the stakeholders, the end users, into the room,” says Wing Commander Reid. “We had an air traffic controller who told us about what it’s like on a dark and stormy night, with zero visibility and a plane coming in with no ADS-B.

“We had a pilot who had a near-miss incident of less than 50 feet. He told us what went through his mind at that particular time – including his three young children.

“We had the Chief Engineer talk to us about the complexities involved in trying to fit this capability into an aircraft with little or no room to fit anything.

“Suddenly all of these tough engineers started to empathise and become design thinkers – and the solutions they came up with were just incredible.”

On the last day of their week with the DIRC the group helped write the requirements for the Hawk 127 project – Wing Commander Reid says such early, comprehensive and open supplier involvement in the requirement definition phase of an acquisition is unheard of in Defence. The tender went out the following week, with 10 days to respond.

“We had 16 responses but, more importantly, four of the companies said they wouldn’t respond because it was not for them and that we had saved them over $2 million in bid costs,” he says.

On the face of it, this project was about building a ‘thing’ for an aircraft, he says. “But what I really care about is the shift in thinking that’s happening.”

The Hawk 127 was an example of design thinking applied to a specific problem, Professor Bucolo says, but design thinking is also being applied to big-picture strategy within the RAAF, showing the way for others.

Wing Commander Reid says defence forces around the world – like many businesses – realise that they can’t sustain an advantage for long, that ‘transient’ advantage is the new normal.

“Our potential adversaries are moving at a pace that is unpredictable, with threats and capabilities increasing rapidly,” he says.

“We develop a capability advantage, and it will last as long as we don’t deploy it. As soon as we deploy it the advantage will be gone – which means we have to have the next capability advantage ready to go, and the next one and the next one.

“To do that we need a system of systems, not just one thing. We need speed and capacity. And design thinking is going to be at the forefront of that.”

https://www.uts.edu.au/research-and-teaching/our-research/design-innovation-research-centre

The kind of partnership approach is crucial to any effort to effectively incorporate new technologies within an open ended approach to program or capability stream development envisaged within joint force design efforts for the ADF.

At the Williams Foundation seminar on Integrated Force Design, the kind of partnerships envisaged in shaping a new acquisition approach was described by Air Commodore Leon Phillips, Director General Aerosapce Maritime, Training and Surveillance, looked at ways to reshape the acquisition and sustainment of the integrated force to address some of the concerns raised by RADM Dalton.

In this presentation, Phillips contrasted the traditional project approach with what he referred to as a new engagement model to allow for more flexibility in development but ways to constrain cost and shape realistic outcomes.

Put bluntly, without organizational change it would not be possible to achieve effective ways to shape integrated design cost effectively and in light of the dynamics of software development.

To achieve a joint design outcome, it would be necessary to shape an engagement model in which industry was a full partner. It was crucial as well to feed learning back into requirements generation as well.

Budgeting changes were required as well.

“We don’t do enough funded work with industry to get a realistic assessment of the domain of the feasible nor with regard to how to price evolving options and capabilities. How do you price the evolution within the force of options and opportunities when you manage with fixed priced contracts? You don’t.”

He argued that the new engagement model would divide programs into three phases: a partnership, appraisal and executive phase within which different approaches would be combined to deliver a capability.

In the partnership phase, one establishes the steering group and the stakeholders to be involved in program definition. The focus is upon the vision or the wish list of the capability, which is the target of the effort.

In the appraisal phase, there are funded studies which allow education about what is realistic to achieve for the target funding and to shape choice and determine how to reduce risk.

In the execution phase, the core decisions have been taken and the target objectives defined and pursued. The execution phase adjusts the vision to realistic outcomes within the targeted budget. It is not about requirements it is about outcomes driven by the partnership as a procurement force.

The industrial presentations made during the seminar highlights various aspects of the challenge in shaping a new working relationship with industry.

Software Upgradeability: Ensuring Transient Combat Advantage

The core importance of shaping software approaches to provide for the kinds of transient advantage necessary to deal with a constantly evolving threat was discussed by Stephen Froelich, Director, Operational Command and Control, Lockheed Martin Rotary and Mission Systems.

In his presentation, Froelich highlighted the importance of open systems architecture, and agile development through software evolution to gain transient advantage. He argued for the importance of a business model that supports an open, agile and spiral development approach.

This requires the simultaneous management of current capability, hardware and fielded capability.

Lockheed is involved in the new submarine program as the combat systems designer and clearly will be involved along with a number of companies teamed with it in providing Navy with the kind of transient advantage necessary for the maritime arm of the ADF.

When I interviewed Chief of Navy prior to the seminar we discussed the new submarine as a case study of the continuous shipbuilding approach which is essential not just to the Navy but to joint force enablement.

Question: One aspect of change clearly is building 21st century defense structure.

I have just returned from the UK and witnessed their significant efforts at Lossiemouth, Waddington, Marham and at Lakenheath to have a new infrastructure built.

And certainly have seen that at RAAF Williamtown with the F-35 and at RAAF Edinburgh with the P-8/Triton.

How important in your view is building a new infrastructure to support a 21st century combat force?

Vice Admiral Tim Barrett: Crucial.

And that is in part what I am referring to as an industrial and national set of commitments to shaping a 21st century combat fleet.

We spoke last time about the Ship Zero concept.

This is how we are focusing upon shaping a 21st century support structure for the combat fleet.

I want the Systems Program Office, the Group that manages the ship, as well as the contracted services to work together on site.

I want the trainers there, as well, so that when we’re maintaining one part of the system at sea, it’s the same people in the same building maintaining those things that will allow us to make future decisions about obsolescence or training requirements, or to just manage today’s fleet.

I want these people sitting next to each other and learning together.

It’s a mindset.

It puts as much more effort into infrastructure design as it does into combat readiness, which is about numbers today.

You want to shape infrastructure that is all about availability of assets you need for mission success, and not just readiness in a numerical sense.

Getting the right infrastructure to generate fleet innovation on a sustained basis is what is crucial for mission success.

And when I speak of a continuous build process this is what I mean.

We will build new frigates in a new yard but it is not a fire and forget missile.

We need a sustained enterprise that will innovate through the life of those frigates operating in an integrated ADF force.

That is what I am looking for us to shape going forward.

Question: An example of your approach to the future is clearly the new submarine.

A French design house and an American combat systems company will be working together really for the first time.

And they are building a submarine which has never been built before.

This provides an opportunity for you to shape a new support structure along the lines you have described going forward.

How do you see this process?

Vice Admiral Tim Barrett: It is something new and allows us to shape the outcome we want in terms of an upgradeable sustainable submarine with high availability rates built in. We intend to see this built that way from the ground up.

It is not simply about acquiring a platform.

We will not be a recipient of someone else’s design and thought.

This will be something that we do, and we will work with those that have a capacity to deliver what we say we need.

I think the way you characterize the process makes sense.

The experiences we’ve had through Collins have taught us a lot.

With 12 of these future submarines in a theater anti-submarine role we think we can make an effective contribution to our defense and to working with core allies in the region, notably the US Navy.

Working the Way Ahead: The Wedgetail Case Study

There were two other industrial presentations at the seminar as well.

The first was by Lt. General (Retired) Jeff Remington of Northrop Grumman and provided him with an opportunity to highlight the challenges to building the joint force seen from an American perspective.

He highlighted how the service specific architectures placed barriers in terms of shaping a more general approach to the integrated force.

And as the key enabler of several Australian systems, Wedgetail and Triton, clearly Northrop is a key player in shaping the way ahead for an evolving integrated force for Australian defense, and one which is interoperable with its closest allies as well.

The Wedgetail case illustrates the path of how the ADF actually got onto the path of working beyond a narrowly requirements dominated approach and taught the ADF and MoD more generally the importance of shaping a new approach.

Boeing is the prime contractor, but Northrop provides the key radar system around which Wedgetail is built.

The Chairman of the Williams Foundation, Air Chief Marshal Brown (Retired) described the learning curve whereby the RAAF got the new capabilities.

Question: As Chief you decided to push your new aircraft – Wedgetail and the KC-30A – out to the force rather than waiting for the long list of tests to be complete.

Why?

Air Marshal (Retired) Brown: Testers can only do so much.

Once an aircraft is functional you need to get in the hand of the operators, pilots, crews and maintainers. They will determine what they think the real priorities for the evolution of the aircraft, rather than a test engineer or pilot.

And you get the benefit of a superior platform from day one.

When I became Deputy Chief of Air Force, the Wedgetail was being slowed down by the Kabuki effort to arrange specification lines for the aircraft. There was much hand-wringing amongst the program staff as to how it didn’t meet the specifications that we had put out.

I said, “Let’s just give it to the operators.”

And the advantage of basically giving the aircraft to the operators was what the test community and the engineers thought were real limitations the operators did not. Sometimes it took the operators two days to figure a work around.

And the real advantage of the development was that they would prioritize what was really needed to be fixed from the operational point of view, not the testing point of view.

In other words, you can spend a lot of time trying to get back to the original specifications.

But when you actually give it to the operators they actually figure out what’s important or what isn’t important and then use the aircraft in real world operations.

And what this has meant is a new working relationship between operators and industry to deliver ongoing modernization of the platform.

This approach was highlighted during my visit to Williamtown last year with the Wedgetail squadron.

Question: It is clearly a system in progress with the capability to evolve into what the US CNO calls a key capability to operate in the electromagnetic battlespace, and to do so for the joint force.

Could you talk about the joint evolution?

Group Captain Bellingham: “Army and navy officers are part of the Wedgetail crew. . We are not just extension of what the air defense ground environment or the control reporting units do from the ground. We take our platform airborne and we do air battle space management.

“Recently, in the Army led Hamel exercise, we pushed the link piecutre down to the ground force headquarters. Their situational awareness became significant, compared to what they have had before.

“And since the Williams seminar on Air-Land integration, several senior Army officers have been to Williamtown to take onboard what we can do and potential evolution of the systems onboard the aircraft.

“We are seeing similar developments on the Navy side. A key example is working with the LHD. My opinion is that the Wedgetail will be critical to making all the bits of an amphibious task group come together. And not just that but as the P-8 joins the force, we can broaden the support to Navy as well. And the new air warfare destroyer will use its systems as well to pass the data around to everyone, and making sure everyone’s connected.

“The E-7 is a critical node in working force integration and making sure we’re all seeing the same thing at the same time, and not running into each other, and getting each other space. We’re not on a ten second scan. We are bringing the information to the war fighter or to whoever needs it right then.”

Question: During the visit, we have been in the squadron building, the hangar and in the System Program Office collocated with the squadron.

What advantages does that bring?

Group Captain Bellingham: “It facilitates a close working relationship between the combat force and the system developers.

“We can share our combat experiences with the RAAF-industry team in the SPO and to shape a concrete way ahead in terms of development.

“The team is very proactive in working collaboratively to get to the outcome we’re looking for.”

https://sldinfo.com/visiting-williamtown-airbase-the-wedgetail-in-evolution/

A New Industrial-Government Working Relationship: The Case of Team Complex Weapons in the UK

Finally, Andy Watson from MBDA missile systems focused on the evolving relationship between industry and government which has generated by the Team Complex Weapons approach of the British government.

According to MBDA:

Team Complex Weapons (Team CW) defines an approach to delivering the UK’s Complex Weapons (CW) requirements in an affordable manner.

This value for money proposition also ensures a viable industrial capacity. The PMA aims to transform the way in which CW business is conducted by MoD with its main supplier.

At the heart of this is a joint approach to the delivery of the required capability based on an open exchange of information and flexibility in the means of delivery.

http://www.mbda-systems.com/about-us/mission-strategy/team-complex-weapons/

A recent example of the fruits of this approach was latest agreement reached between MBDA and the UK government. According to the British government:

Secretary of State, Sir Michael Fallon, has today (April 21, 2017) announced three new missile contracts worth a combined £539 million for state-of-the-art Meteor, Common Anti-air Modular Missile (CAMM) and Sea Viper missile systems at MBDA Stevenage.

The deal ensures our Armed Forces have the best equipment available to protect the new Queen Elizabeth Class Carriers and the extended fleet from current and future threats.

The half a billion-pound contracts will sustain over 130 jobs with MBDA in the UK, with missile modification and service support being carried out in Stevenage, Henlow, Bristol and Bolton.

Secretary of State, Sir Michael Fallon, said:

“This substantial investment in missile systems is vital in protecting our ships and planes from the most complex global threats as our Armed Forces keep the UK safe.

“Backed by our rising Defence budget, these contracts will sustain high skilled jobs across the UK and demonstrate that strong defence and a strong economy go hand in hand…..”

Meanwhile, a £175 million in-service support contract for the anti-air Sea Viper weapon system will ensure that the Royal Navy’s Type 45 Destroyers can continue to provide unparalleled protection from air attack to the extended fleet. Under the contract, the missiles will be maintained, repaired and overhauled as and when required to ensure continued capability.

The Sea Viper missile defends ships against multiple threats, including missiles and fighter aircraft.

The final contract is a £323 million deal to purchase the next batch of cutting-edge air defence missiles for the British Army and Royal Navy, offering increased capability at a lower cost. Designed and manufactured by MBDA UK at sites in Bolton, Stevenage and Henlow, the next-generation CAMM missile will provide the Armed Forces with missiles for use on sea and on land. CAMM has the capability to defend against anti-ship cruise missiles, aircraft and other highly sophisticated threats.

Signalling our continued investment in Type 26 programme, CAMM will provide the anti-air defence capability on the new Type 26 Frigates for the Royal Navy and will also form part of the Sea Ceptor weapon system on the Type 23 Frigate and will also enhance the British Army’s Ground Based Air Defence capability by replacing the in-service Rapier system.

Tony Douglas, Chief Executive Officer of Defence Equipment and Support, the MOD’s procurement organisation, said:

“Work on these cutting-edge missiles, which will help to protect the UK at home and abroad and secure jobs across the country, demonstrates the importance of Defence investment. That is why, working closely with our industry partners, we continue to drive innovation and value into everything we do; securing next generation equipment for our Armed Forces at the best possible value for the taxpayer.”

Dave Armstrong, Managing Director of MBDA UK, added:

“MBDA is delighted by the continued trust placed in us by the Ministry of Defence and the British military.

“The contracts announced today for Meteor, CAMM and Sea Viper will help protect all three UK Armed Services, providing them with new cutting-edge capabilities and ensuring their current systems remain relevant for the future.

“They will also help to secure hundreds of high-skilled people at MBDA UK and in the UK supply chain, maintaining the UK’s manufacturing base and providing us with a platform for exports.”

Shaping A Way Ahead

In short, reshaping Government’s approach to working with government and expanding the portfolio of partnering arrangements is essential to generating the intellectual capital, property rights, and innovations necessary to deliver a dynamic integrated combat force.

New approaches to shaping outcomes from the acquisition engagement process are crucial in order to empower successful partnering arrangements.

After the seminar, I had a chance to talk with Chris Jenkins, head of Thales Australia, and National President of the Australian Industry Group with regard to the challenge of reshaping the Government-Industry partnership.

Question: The Australian government has set in motion a significant modernization programs. What is the role and impact on industry?

Chris Jenkins: There are several aspects to that subject.

Australia is spending more on defense. At the same time as doing so, there have been clear changes within defense as an organization to shape new ways to implement that policy, following the First Principles Review and its recommendations.

There’s also been very clear policy around enhancing the impact of defense modernization on Australian industrial skill sets. There has been keen interest to enhance the level of engineering and technology and program management skills and to grow those skills over the long term, both within the Defence industry sector but also more broadly in Australian industry.

I’ve been really impressed that within a very short period of time there’s been buy-in from the defense service chiefs, and changes within the defense acquisition and sustainment organization to start to implement these policies and make them real.

Overall the most important impact, in my view, is the inclusion of industry as a Fundamental Input to Capability (FIC) for Defence. This drives a new, more integrated relationship with mutual responsibilities between Defence and industry.

This really gets to the heart of how industry can be engaged as a FIC. Finding more effective paths to deliver integrated capabilities within and across Defence platforms and systems is something that can only be done efficiently by close partnering between Defence and industry.

Question: I spent time with the head of Air Force this morning, Air Marshal Davies, and he is keen on shaping an integrated force. It is not just about platforms, but finding ways to deliver integrated capabilities.

What is the challenge and impact on industry of such an approach?

There are very clear actions being taken to support that by the service chiefs and by the people in the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group. You’re also seeing industry gaining confidence in the approach as the new paradigm. Industry is also starting to work more collaboratively together, forming the team sets that can deliver and evolve combined platform and system capability. Companies are starting to work together to share workload because of the complementarity of the skill sets that one company might have compared to another.

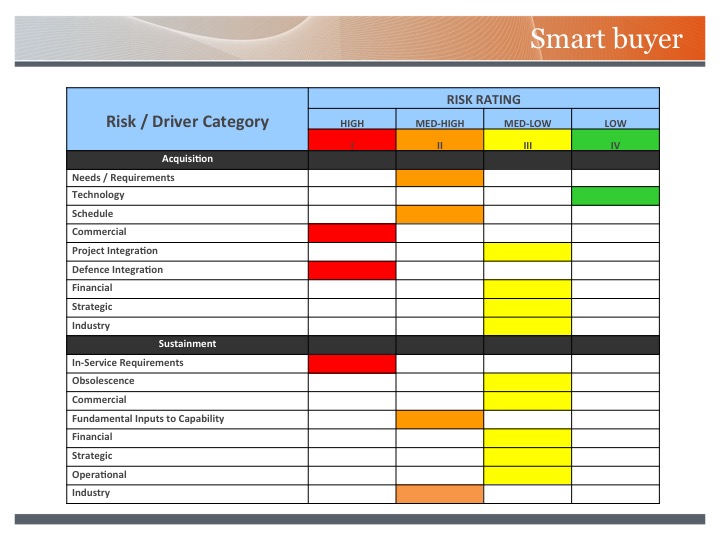

This slide was presented as part of Rear Admiral Tony Dalton, Head Joint Systems Division, Australian Ministry of Defence’s brief to the Williams Foundation Seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017.

This slide was presented as part of Rear Admiral Tony Dalton, Head Joint Systems Division, Australian Ministry of Defence’s brief to the Williams Foundation Seminar on Integrated Force Design, April 11, 2017.

Industry is responding to the opportunity to engage in a collaborative set of partnerships between defense and industry and this is showing some good results in terms of greater delivery and sustainment capability.

Prior to these government initiatives, Australia has been one of the lower end performers on collaborative development. Reshaping this relationship is crucial to get the kind of success Australia wants through more efficient, more agile integrated capability delivery.

Question: Clearly, this means that even when platforms are bought abroad, there needs to be a working relationship where that platform evolves over time within an ADF context, not simply replicating whatever has been done to modernize the platform in the originator’s home market.

How will Australia do that?

Chris Jenkins: There’s a smart buyer approach in the market now, which is looking for the elements that will go onto the key platforms that are specifically focused on the Australian defense requirement.

Rather than buying a complete platform and system from overseas off the shelf, I think the realization is Australia does have some unique operational requirements, and so building into the procurement process a way of evaluating how best to bring those teams together that can deliver and sustain those requirements through the life of the vehicle, or the ship or whatever it might be, is being done more efficiently and effectively.

The customer is helping shape the market or the way the market responds to the requirements more effectively. I think that is a fundamental change.

How well projects deliver as a consequence of that overall change, time will tell, but I think all signs are actually quite positive.

The first principles review made strong recommendations, and it looks like that the actions that need to underpin those recommendations are being taken.