With changes in the region, and with new dynamics of change in the North Atlantic, how might Australia rethink its defense policy?

It is clear that the current government has put in place a fundamental transformation of Australian defense policy with the RAAF being significantly modernized, the navy recapitalized but a decade away from seeing the force transformation to be deployed and Army reworking how best to contribute to the transformation effort.

This provides a solid foundation for the way ahead but how best to proceed in the future as the foundation is transformed?

Clearly, a key aspect will be thinking through longer range strike and defense in depth capabilities. In fact, the two might be combined as Australia looks to build a 21st century version of operating from flexible basing throughout Australia as fixed bases become high value targets.

Might the Army become a key force operating land based longer range strike and building up its capabilities to defend mobile air bases?

These are issues which we will explore in the coming months.

But during this visit to Australia, we had a chance to meet with Paul Dibb, emeritus professor of strategic studies at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre which is part of the Australian National University.

And during that meeting, he brought to our attention a piece c0-authored last year with Richard Brabin-Smith which provided an interesting look at rethinking Australia’s defense policy in the new strategic era.

What follows is the executive summary to that paper published by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

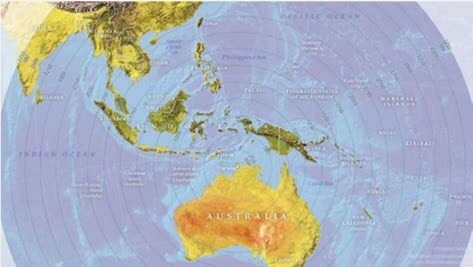

Australia’s strategic outlook is deteriorating and, for the first time since World War II, we face an increased prospect of threat from a major power.

This means that a major change in Australia’s approach to the management of strategic risk is needed.

Strategic risk is a grey area in which governments need to make critical assessments of capability, motive and intent. Over recent decades, judgements in this area have relied heavily on the conclusion that the capabilities required for a serious assault on Australia simply did not exist in our region.

In contrast, in the years ahead, the level of capability able to be brought to bear against Australia will increase, so judgements relating to contingencies and the associated warning time will need to rely less on evidence of capability and more on assessments of motive and intent. Such areas for judgement are inherently ambiguous and uncertain.

In particular, China’s economic and political influence continues to grow, and its program of military modernisation and expansion is ambitious.

The latter means that the comfortable judgements of previous years about the limited levels of capability within our region are no longer appropriate. The potential warning time is now shorter, because capability levels are higher and will increase yet further.

This observation applies both to shorter term contingencies and, increasingly, to more serious contingencies credible in the foreseeable future.

It’s important not to designate China as inevitably hostile to Australia, and to recognise in any case that there would be constraints on the expansion of its military influence.

Beyond the short to medium term, there would be intrinsic difficulties in operating in waters potentially dominated by Indian anti-access capabilities, and there’s potential, too, for Indonesia to develop significant sea-denial capabilities.

Nevertheless, China’s aggressive policies towards the South China Sea and elsewhere are grounds for concern that it seeks political domination over countries in its region, including countries in Southeast Asia and including Australia.

It’s China, therefore, that could come to pose serious challenges for Australian defence policy.

We need also to keep a watchful eye on Indonesia against the possibility that Islamist extremism will come to dominate that country.

This isn’t the country’s current trajectory, but the security consequences for Australia of such a development would be severe, especially if Indonesia over the years ahead were to become a major regional power.

How should Australia respond?

Contingencies that are credible in the shorter term could now be characterised by higher levels of intensity and technological sophistication than those of earlier decades.

This means that readiness and sustainability need to be increased: we need higher training levels, a demonstrable and sustainable surge capacity, increased stocks of munitions, more maintenance spares, a robust fuel supply system, and modernised operational bases, especially in the north of Australia.

For the longer term, the key issue is whether there’s a sound basis for the timely expansion of the ADF.

In many ways, the expansion base is impressive, in that relevant capabilities already exist or are in the forward program, although not necessarily in the right numbers.

Matters that would benefit from specific examination include the development of an Australian equivalent of an anti-access and area denial capability (especially for our vulnerable northern and western approaches) and an improved capacity for antisubmarine warfare.

In summary, the prospect of shortened warning times now needs to be a major factor in today’s defence planning.

Much more thought needs to be given to planning for the expansion of the ADF and its capacity to engage in high-intensity conflict in our own defence—in a way that we haven’t previously had to consider.

Planning for the defence of Australia needs to take the new realities into account, including by re-examining the ADF’s preparedness levels and the lead-times for key elements of the expansion base.

The conduct of operations further afield, and Defence’s involvement in counterterrorism, must not be allowed to distract either from the effort that needs to go into this planning or from the funding that enhanced capabilities will require.

https://sldinfo.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/ASPI-MANAGING-RISK-FINAL-NOVEMBER-2017.pdf