By Richard Weitz

In late August, 2018 the Chinese Foreign Ministry published its position paper regarding the 73rd session of the UN General Assembly, which will run from September 18 and October 5 in New York.

In this document, Beijing has again professed concern about the militarization of space—somewhat awkwardly given China’s growing military capabilities in this realm.

According to the paper, “The Chinese government stands for the peaceful use of outer space and opposes weaponization and arms race in outer space.”

Beijing has stated this position for years, well before President Trump and others called for a Space Force to better address Chinese threats in the space realm.

Though it began years after the U.S. and Soviet (Russian) space programs, China has demonstrated a strong commitment to develop space power. PRC leaders view development of outer space as necessary for the country to achieve military, economic, and political security.

Space provides China with ample opportunities to grow economically (i.e. commercial launches, advancing aerospace technology) and also to become stronger militarily (i.e. improving methods of accessing and controlling information).

Since Xi Jinping became president in 2013, China’s civilian space program has shown great strides. That year, China became the first country in decades to land a spacecraft on the moon. Its Jade Rabbit rover spent two years investigating the lunar surface.

Since then, China has been sending spacecraft into earth and lunar orbit in preparation for landing a spacecraft on the moon’s remote far side later this year.

Other goals include landing an astronaut on the moon by 2025, send a probe to Mars that returns soil samples to earth in 2028, and establish a permanent research and mining facility on the moon by 2050.

Chinese military writings specifically highlight the need to interfere with, damage, and destroy reconnaissance, navigation, and communication satellitesto “blind and deafen the enemy.”

People’s Liberation Army analysts of U.S. and coalition military operations note that “destroying or capturing satellites and other sensors … will deprive an opponent of initiative on the battlefield and [make it difficult] for them to bring their precision guided weapons into full play.”

While the 2015 Chinese military strategy white paper states that the Chinese are officially opposed to the weaponization of space, it observes that the PLA shall “deal with security threats and challenges in that domain, and secure its space assets to serve its national economic and social development, and maintain outer space security.”

The Chinese government describes its national defense policy, including space policy, as “purely defensive in nature,” but Western experts note that Mao described “active defense” as “offensive defense or defense through decisive engagements…for the purpose of counter-attacking and taking the offensive.”

In other words, Beijing’s “active defense” policy is “politically defensive,” but “operationally offensive”.

According to testimony offered earlier this year by the head of the Defense Intelligence Agency, “the PLA continues to strengthen its military space capabilities despite its public stance against the weaponization of space.

“Beijing has invested in space system improvements, with an emphasis on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems, satellite communications, satellite navigation, meteorology, and human spaceflight and interplanetary exploration.”

China also continues to develop a variety of counterspace capabilities designed to limit or prevent an adversary’s use of space-based assets during crisis or conflict.

The latest Chinese Military Power report released last month states that Chinese strategists regard space and counterspace capabilities as “central to modern warfare.”

The report sees China’s space priorities as achieving “the unconditional security of network data across long distances, ultimately creating a global quantum network of classical (i.e.non-quantum) data secured by quantum cryptographic keys,” as well as the deployment and “hardening” of an growing constellation of multi-purpose satellites.

When Vice President Mike Pence announced the new U.S. space policy last month, he cited China’s 2007 downing of one of its satellites as a “highly provocative demonstration of China’s growing capability to militarize space.”

Since then, China has been developing a portfolio of kinetic and non-kinetic anti-satellite (ASAT) weaponry, include a direct ascent ASAT system that deploys on a ballistic missile, a co-orbital ASAT that can maneuver in space into a target, a spacecraft with a robotic arm to seize adversary satellites, and a hit-to-kill exo-atmospheric kinetic interceptor that could hit missiles as well as satellites.

The United States has more military and commercial satellites than any other country. The Pentagon relies on space- based assets for communications, reconnaissance, intelligence, navigation, and targeting.

To protect its own communications, China recently launched the world’s first quantum communications satellite.

The Trump administration has made a strong effort to counter Chinese space threats.

The administration has vowed to increase U.S. investment in anti-satellite defenses and has called for creating a new Space Force to better manage the era of renewed great power competition.

On August 28, Secretary of Defense James Mattis and Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford detailed plans to enhance U.S. military space capabilities by increasing lethality; strengthening international alliances; and reforming economic efficiency within the department.

The Department plans to establish a unified space command, upgrade the space acquisition processes, and work with Congress to build a separate space force.

Meanwhile, the Pentagon should continue to strive to decrease reliance on satellite resources (such as employing more land and UAV links) and make all these links more resilient by increasing redundancies in communications links and interoperability with allies and partners.

There is a need as well to expand use of commercially available launch facilities to enlarge the fleet of satellites and the means to rapidly replace them, as well as prepare, in doctrine and exercises, to fight with only degraded data and communications.

Furthermore, U.S. diplomacy needs to harmonize its space policies better with its European partners.

Despite U.S. limits on space engagement with Beijing, China has significantly increased international cooperation with other countries, especially the European Space Agency (ESA) and Roscosmos.

The ESA has designated the Chinese National Space Administration as one of its strategic partners, alongside Russia and United States.

This lack of unity on the part of Western countries makes it harder to achieve the shared goal of directing China’s space programs in less threatening directions.

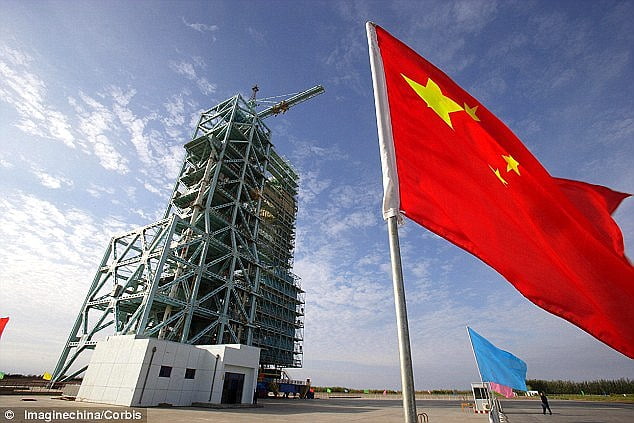

The featured graphic is attributed to the following source: