The Ministry of Defence of Singapore has started its process of formally replacing their legacy fleet with the F-35.

An article by Andrew McLaughlin published in the Australian Defence Business Review on January 19, 2019 focused on the decision by Singapore’s Ministry of Defence.

The Republic of Singapore Air force (RSAF) and Singapore Defence Science and Technology Agency (DSTA) have selected the Lockheed Martin F-35 to replace the RSAF’s fleet of F-16 fighters.

The intensive study and technical evaluation process commenced in 2013 but was paused for two years due to ongoing delays to the JSF program and a decision to upgrade the RSAF’s F-16s, but resumed in 2017. Along with Israel, Singapore has been a JSF Program Security Cooperation Participant (SCP) since 2004, which has given it an insight into the program’s development and status throughout its often-troubled development.

“Happy to report that DSTA Defence Science and Technology Agency and RSAF have completed their technical evaluation for the replacement,” a social media post by Singapore’s Defence Minister, Ng Eng Hen reads.

“It took longer than expected – more than five years – as they had to go through in detail specifications and needs, which they could only do after developmental flight testing of the F-35s was completed in early 2018. They have decided that the F-35 would be the most suitable replacement fighter.”

The RSAF currently operates about 60 F-16C/D Block 52s and Block 52 D+ Advanced models, the oldest of which entered service in 1998. All of the F-16s are currently being upgraded to the latest F-16V standard with AESA radars and other improvements, and the RSAF maintains a training detachment of the jets at Luke AFB in Arizona.

The evaluation recommended the acquisition initially of a small number of F-35s for a full evaluation and assessment before the RSAF commits to a full fleet of between 40 and 60 aircraft to equip three squadrons. It is unclear whether the RSAF favours the conventional takeoff and landing F-35A model, or the short take off and vertical landing (STOVL) F-35B, or a mix of both.

“Our agencies will now have to speak to their US counterparts to move the process forward, which may take 9 – 12 months before a decision is made,” Mr Ng said.

“Even then, we want to procure a few planes first, to fully evaluate the capabilities of the F-35 before deciding on the acquisition of a full fleet. We must prepare well and cater enough time to replace our F-16s.”

The island nation has very limited airspace in which to operate and land upon which to build runways and base facilities, so despite its reduced combat capabilities over the A model, the F-35B has always been seen as a practical option. The F-35B also has the advantage of being able to deploy aboard Singapore Navy and allied amphibious carriers if required.

The RSAF also operates 36-40 Boeing F-15SG fighters, and a small number of Northrop F-5E/Fs in the air combat roles.

Joseph Trevitchik noted in an article published on January 18, 2019 that Singapore with this decision has moved closer to joining what China calls the US F-35 friends circle.

China is only expanding its anti-access and area-denial capabilities in the South China Sea, especially when it comes to its made-made islets. Many of these have, or could readily accommodate, long-range surface-to-air missiles and shore-based anti-ship defenses that would present a significant challenge to any potential opponent in a crisis.

The Chinese have also demonstrated their ability to fly H-6 medium bombersand smaller combat jets from those islands, giving them additional options to project power. This is to say nothing of the steadily expanding and improving surface ships and submarines of the People’s Liberation Army Navy.

A stealthy fighter may simply soon become a requisite for any country in the region who is looking to present a credible challenge to those developments.

The obvious threat the F-35 specifically poses has led Chinese media to downplay it and derisively dub Joint Strike Fighter operators in the Pacific region, which includes Australia, South Korea, and Japan, so far, as the “U.S. F-35 friends circle.”

As such, evaluating the jet is a logical course of action for Singapore given its relationship with the United States and the simple fact that the aircraft is in production now. At the same time, the country’s “fly-before-you-buy” approach shows that they’re willing to take the time to fully explore their options.

Singapore’s F-16C/D Block 52/52+ aircraft are quite advanced and have already received significant upgrades over the years.

The country is now in the process of upgrading those jets to the even more advanced F-16V configuration, which could help keep them relevant beyond 2030 if necessary.

The decision is hardly a surprise given that Singapore trains on both Australian and US territory and understands the advantage of being able to operate with the Pacific fleet of F-35s being stood up in South Korea, Japan, Australia, the US and European allies who come to the region, such as the UK onboard their new class of carriers.

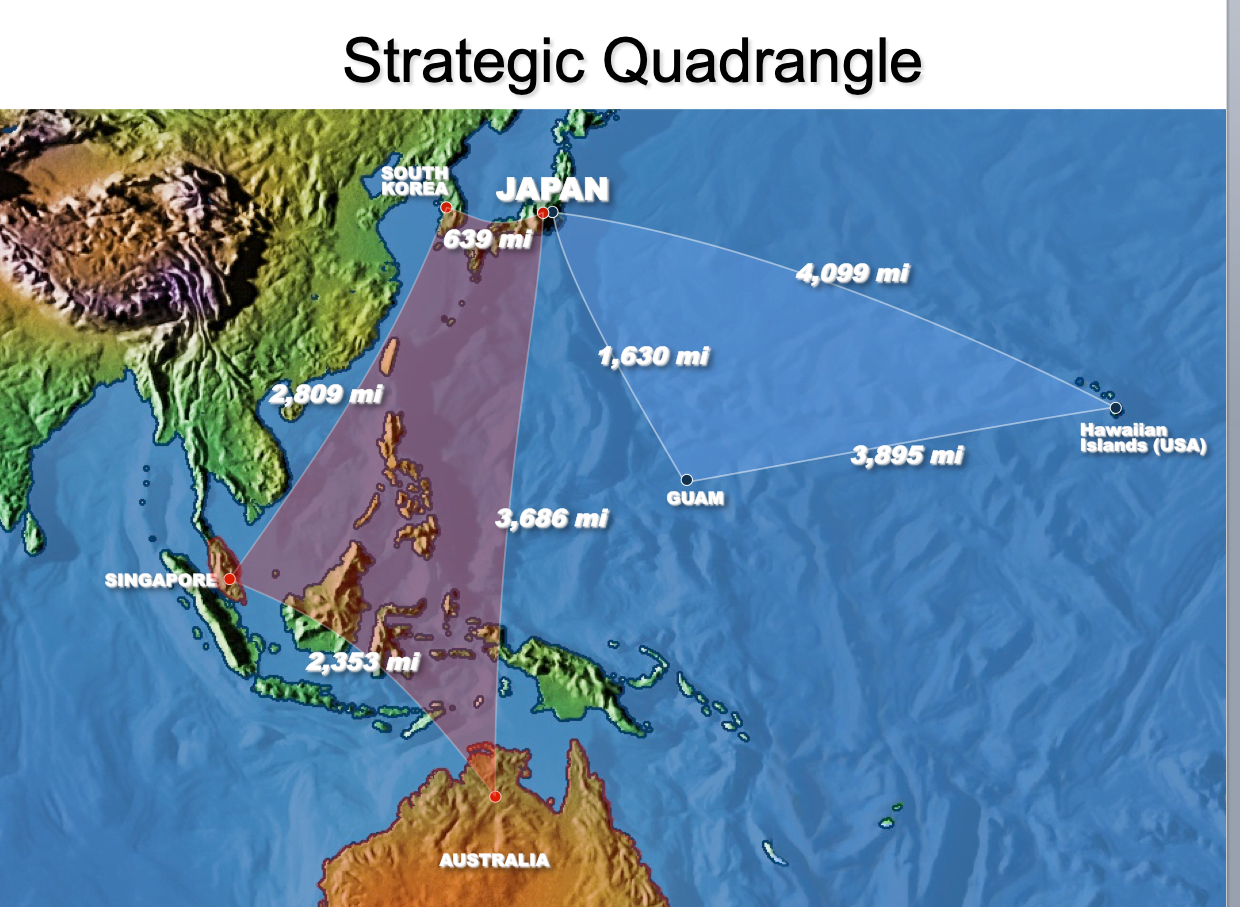

If one looks at the strategic context, the strategic quadrangle which encompasses the allies who face the Chinese military extended reach provides a base line from understanding why the F-35 makes sense. We wrote a book several years ago which highlighted the synergy between technology and geography in the region, and also highlighted the capabilities of the aircraft to integrate with active defense systems, a key capability which the US and allies clearly need as well.

The challenge of reshaping Pacific defense to deal with the various strategic challenges of the 21st century – the Arctic opening, SLOC and maritime trade conveyer belt security, North Korea and the dynamics of the second nuclear age, and the reaching out into the Pacific by the PRC – is about augmenting Pacific defense and an ability of the U.S. and its allies to operate collaboratively over the geographic expanse of the Pacific.

What we have called the strategic quadrangle in the Pacific is a central area where the U.S. and several core allies are reaching out to shape collaborative defense capabilities to ensure defense in depth.

This area is central to the operation of forces from Japan, South Korea, Australia, India, Singapore and the United States, to mention the most important allies.

Freedom to operate in the quadrangle is a baseline requirement for allies to shape collaborative capabilities and policies. Effectiveness can only emerge from exercising evolving forces and shaping convergent concepts of operations.

In our book on the shaping of a 21st century strategy, we highlight Pacific operational geography as a key element for forging such a strategy.

In effect, U.S. forces operate in two different quadrants—one can be conceptualized as a strategic triangle and the other as a strategic quadrangle.

The first quadrant—the strategic triangle—involves the operation of American forces from Hawaii and the crucial island of Guam with the defense of Japan. U.S. forces based in Japan are part of a triangle of bases, which provide for forward presence and ability to project power deeper into the Pacific.

The second quadrant—the strategic quadrangle—is a key area into which such power needs to be projected. The Korean peninsula is a key part of this quadrangle, and the festering threat from North Korea reaches out significantly farther than the peninsula itself.

The continent of Australia anchors the western Pacific and provides a key ally for the United States in shaping ways to deal with various threats in the Pacific, including the PRC reach deeper into the Pacific with PRC forces. Singapore is a key element of the quadrangle and provides a key ally for the United States and others in the region.

A central pressure in the region is that each of the key allies in the region works more effectively with the United States than they do with each other.

This is why the United States is a key lynchpin in providing cross linkages and cross capabilities within the region. But it is clear that over time a thickening of these regional linkages will be essential to an effective 21st-century Pacific strategy.

The distances in these regions are immense.

For the strategic triangle, the distance from Hawaii to Japan are nearly 4,100 miles. The distance from Hawaii to Guam—the key U.S. base in the Western Pacific—is nearly 4,000 miles. And the ability of Guam to work with Japan is limited by the nearly 2,000-mile distance between them as well.

For the strategic quadrangle, the distances are equally daunting. It is nearly 4,000 miles from Japan to Australia. It is nearly 2,500 miles from Singapore to Australia and nearly 3,000 miles from Singapore to South Korea.

Clearly, air and naval forces face significant challenges in providing presence and operational effectiveness over such distances.

This is why a key element of shaping an effective U.S. strategy in the Pacific will rest on much greater ability for the allies to work together and much greater capability for U.S. forces to work effectively with those allied forces.

The allies are looking to the operational quadrangle as a key area within which to project force outwards and to find ways to expand both the effectiveness and survivability of a flexible force.

Air platforms have the distinct advantage of flexibility in operations, and with an ability to operate from various land and sea bases can operate from different trajectories of operation as well.

The common infrastructure being built to facilitate an F-35 global enterprise clearly is important to Singapore and its capabilities to operate in the region in a crisis and to shape its engagement with an effective allied coalition.

In addition, the technology being shaped, notably with the F-35B, is crucial as well to the geography of Singapore itself.

In addition, the technology being shaped, notably with the F-35B, is crucial as well to the geography of Singapore itself.

As Ed Timperlake put it in an article published in 2012 entitled “strategic deterrence with tactical flexibility:”

Every fighter pilot has had or will have a moment in the air when the biggest indicator in the cockpit is showing how much fuel is left: the fuel indicator immediately can dominate the pilots attention and really focus thinking on where to immediately land.

Fuel is measured in pounds usually with an engineering caveat stating a degree of uncertainty over how low the number may go before all the noise will stop. Pounds of fuel remaining eventually become everything.

It is actually a very simple and terrifying equation, no fuel means simply no noise because the jet engine has stopped working.

Contemplating this very time sensitive dilemma, when the “noise gage” goes to zero, all pilots know that their once trusted and beautiful sleek multi-million fighters that they are strapped into will rapidly take on the flying characteristic of a brick.

Running low on fuel, calling “bingo,” on the radio which is announcing min fuel left for a successful recovery and then realizing you are actually going below “bingo” could occur for a variety of reasons.

In peacetime it is mostly a delay in landing because of weather related issues.

In combat, in addition to horrific weather at times, throw in battle damage to the fuel tanks and it becomes a real life or death problem.

In peacetime you can eject, probably lose your wings and that will be that.

However, in combat, in addition to shooting at you the enemy always gets a vote on other methods to kill you and destroy your aircraft. They will use any means possible.

Consequently if aircraft in their combat strike package get lucky and a few survive to bomb “homeplate” taxiways and all divert fields it can become a significant problem.

Even more realistically in this 21st Century world, missile proliferation, both in terms of quality and quantity, is a key challenge. All nations can be peer competitors because of weapons proliferation.

An enemy may have successfully improved the quantity and quality of their missile such that an Air Battle commander’s entire airborne air force can be eliminated by the enemy destroying all runways, taxiways and divert bases.

In a war at sea, hitting the carrier’s flight deck can cripple the Carrier Battle Group (CBG) and thus get a mission kill on the both the Carrier and perhaps even the entire airborne air wing if they can not successfully divert to a land base.

With no place to land, on the sea or land and with tanker fuel running low, assuming tankers can get airborne, the practical result will be the loss of extremely valuable air assets.

In such circumstances, The TacAir aircraft mortality rate would be the same as if it was during a combat engagement with either air-to-air or a ground –to-air weapons taking out the aircraft.

The only variable left, between simply flaming out in peacetime, vice the enemy getting a kinetic hit would be potential pilot survivability to fly and fight another day.

However, with declining inventories and limited industrial base left in U.S. to surge aircraft production a runway kill could mean the loss of air superiority and thus be a battle-tipping event, on land or sea.

Now something entirely new and revolutionary can be added to an Air Force, the VSTOL F-35B.

Traditionally the VSTOL concept, as personified by the remarkable AV-8, Harrier was only for ground attack. To be fair the RAF needed to use the AV-8 in their successful Falklands campaign as an air defense fighter because it was all they had.

The Harrier is not up to a fight against any advanced 4th gen. aircraft—let alone F-22 5th Gen. Fighters that have been designed for winning the air combat maneuvering fight (ACM) with advanced radar’s and missiles.

Now though, for the first time in history the same aircraft the F-35 can be successful in a multi-role.

The F-35, A, B &C type, model, series, all have the same revolutionary cockpit-the C4ISD-D “Fusion combat system” which also includes fleet wide “tron” warfare capabilities.

There has been a lot written about the F-35B not being as capable as the other non-VSTOL versions such as the land based F-35A and the Large carrier Battle Group (CBG) F-35, the USN F-35C.

The principle criticism is about the more limited range of the F-35B. In fact, the combat history of the VSTOL AV-8 shows that if properly deployed on land or sea the VSTOL capability is actually a significant range bonus. The Falklands war, and recent USN/USMC rescue of a Air Force pilot in the Libyan campaign proved that.

The other key point is limited payload in the vertical mode. Here again is where the F-35 T/M/S series have parity if the F-35B can make a long field take off or a rolling take off from a smaller aircraft carrier-with no traps nor cats needed it can carry it’s full weapons load-out.

The Royal Navy just validated this point by reversing back to the F-35B.

Give all aircraft commanders the same set of strategic warning indicators of an attack because it would be a very weak air staff that would let their aircraft be killed on the ground or flight deck by a strategic surprise.

Consequently, the longer take off of the F-35 A, B or C with a full weapons complement makes no difference. Although history does show that tragically being surprised on the ground has happened.

Pearl Harbor being the very nasty example. Of course, USN Carrier pilots during the “miracle at Midway” caught the Japanese Naval aircraft being serviced on their flight deck and returned the favor to turn the tide of the war in the pacific.

In addition to relying intelligence, and other early warning systems to alert an air force that an attack is coming so “do not get caught on the ground!” dispersal, revetments and bunkers can be designed to mitigate against a surprise attack.

Aircraft survivability on the ground is critical and a lot of effort has also gone into rapid runway repair skills and equipment to recover a strike package. All F-35 TMS have the same advantages with these types of precautions.

The strategic deterrence, with tactical flexibility, of the F-35B is in the recovery part of an air campaign when they return from a combat mission, especially if the enemy successfully attacks airfields.

Or is successful in hitting the carrier deck-they do not have to sink the Carrier to remove it from the fight just disable the deck. War is always a confused messy action reaction cycle, but the side with more options and the ability to remain combat enabled and dynamically flexible will have a significant advantage.

With ordinance expended, or not, the F-35B does not need a long runway to recover and this makes it a much more survivable platform — especially at sea where their might be no other place to go.

A call by the air battle commander-all runways are destroyed so find a long straight road and “good luck!” is a radio call no one should ever have to make.

But something revolutionary now exists.

In landing in the vertical mode the Marine test pilot in an F-35B, coming aboard the USS Wasp during sea trials put the nose gear in a one square box. So the unique vertical landing/recovery feature of landing anywhere will save the aircraft to fight another day.

It is much easier to get a fuel truck to an F-35B than build another A or C model, or land one of the numerous “decks” on other ships, even a T-AKE ship then ditch an F-35C at sea.

This unique capability can be a war winning issue for countries like Israel, Taiwan and the U.S. Navy at sea.

In an article by Mike Yeo published on July 10, 2018, the reporter addressed how the F-35 would enhance Singapore’s regional operational capabilities.

There are several regional air forces already buying F-35s with Australia, an F-35 development partner country who has a close security relationship with Singapore, ordering 72 F-35As.

Australia is also building facilities and infrastructure to support its own F-35s, which includes threat emitter systems to simulate hostile radar and air defences in the same training areas RSAF fighters have used in the past as part of the training agreements Singapore has signed with Australia. These could potentially be used by the RSAF to train with in the future.

In northeast Asia, both Japan and South Korea have ordered F-35As for their own air forces and have reportedly looked into the possibility of operating F-35Bs from ships of their respective navies.

The United States military also plans to deploy F-35s to its forward-deployed forces based in the region, with one squadron of US Marine Corps F-35Bs already based in Japan while more US Air Force and Navy fighter squadrons based in Japan are expected to convert to the F-35 over the next decade.

This will create a significant pool of F-35 users in the region, which will potentially enhance interoperability among these nations during any multinational coalition operations.

Australian companies have also successfully secured the rights to conduct heavy maintenance and warehousing of spare parts for regional F-35 operators, and this would streamline sustainment and supply chain matters should Singapore opt for it as the next fighter jet.

And certainly the F-35’s integrated sensor and C2 capabilities will fit nicely into the core IKC2 design of their force as well. We will close with the article we first published in 2012 which explained the core Singapore defense transformation approach which clearly anticipate the coming of the F-35 as well.

Singapore is a non-aligned power with close ties to the United States politically and militarily and close ties with China economically and politically. They depend on the security of maritime trade and the safety and security of the global commons.

They have built a modern naval and air force and are investing in its further modernization. And their efforts are founded on working with Western countries and firms in shaping an effective modernization strategy. And they are seeking to ensure that the force is well integrated and networked. Their concept for doing so is called an Integrated Knowledge Command and Control Concept, which is their version of the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA).

This concept is well articulated on Singapore’s Ministry of Defense website as follows:

On the ground and in the jungles, the SAF will transform into a lean, networked and lethal fighting force while staying focused on the new security challenges. It will employ new technologies, such as precision fire, advanced communications and information technology, as well as unmanned vehicles, to defeat potential adversaries. At the same time, innovative warfighting concepts in combined arms operations, urban fighting and infantry fieldcraft will be introduced in tandem to provide the SAF with the operational edge.

Out at sea, the SAF will achieve potent three-dimensional fighting capabilities in the air, on the surface, and under the sea. Its ships will also have the command and control capability to conduct seamless operations as an integrated force with aircraft and land forces, through effective use of advanced communications and information technology, while leveraging on platform strengths. The SAF should thus be ready to meet the full spectrum of maritime threats, including small, fast-moving boats in the littorals that can otherwise pose a tremendous challenge to traditional naval forces.

In the air, the SAF will achieve Air Dominance through the coordinated employment of fighters, unmanned air vehicles and airborne surveillance aircraft, which are integrated through real-time knowledge-based systems and networks. The networked force will have comprehensive situational awareness that gives the critical edge in air operations. The SAF will also marry advanced surveillance and strike capabilities over surface threats, including elusive targets that may be concealed under foliage or ships out on open sea.

Finally, tying all these air, land and sea capabilities together into a synergistic whole is the concept of Integrated Knowledge-based Command and Control (IKC2). The concept gives commanders and soldiers the ability to see first, see more; understand better; decide faster; so that they can act decisively to achieve victory. This is achieved by leveraging on networks of sensors, shooters and communications to provide comprehensive awareness and self-synchronization on the battlefield. The networks also provide wells of information, which will also be translated into relevant knowledge for superior decision-making to achieve precise effects, and effectively shape the battlefield.

To understand the Singapore approach and its place in the world, Second Line of Defense discussed Singapore and the defense situation in Asia with Richard Bitzinger. Bitzinger is a leading expert on defense issues in the Pacific, and has focused much of his recent work on the evolving PRC policies. He teaches and works in Singapore and provides support for Singapore’s thinking about the RMA.

He is a Senior Fellow with the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

SLD: How would you describe Singapore’s defense orientation?

Bitzinger: Singapore is non-aligned.

But it operates closely with the United States and allies in the region. They buy Western equipment, provide a leasing arrangement for the US navy to operate in Singapore and train in several allied facilities in the region.

They train for tank warfare in Australia, they train for jungle warfare in Brunei, they do infantry training in Taiwan, fighter training in the U.S. and have a working relationship for training in France.

At the same time, they have close economic and political ties with China. A balancing act is central to Singapore’s security policies in the region.

There has been a clear shift in the past few years.

Prior to this period, the main focus of military modernization for Singapore has been upon dynamics in Southeast Asia, and preparing for threats from countries like Malaysia and Indonesia. Now this concern is being superseded by the perceived need to deal with the military rise of China.

SLD: With regard to the modernization and development of their forces, and given their geography, it seems Singapore is shaping an extended defense and security bubble to surround themselves with an integrated naval and air force.

Is this the case?

Bitzinger: The defense bubble concept does make sense in describing Singapore’s approach to modernization.

The Singaporeans see technology as their force multiplier. They have a conscript Army, and a relatively large mobilization force. But the ability to leverage technology to bring air, sea and ground into a more effective force is crucial to their approach.

They are creating what they call a 3G Singapore Armed Forces or 3GSAF. They are looking to shape an effective networked and integrated force with the Navy and the Air Force in the lead, with the goal of providing an intelligently informed ground force element.

SLD: It would seem then that the F-35 as a C5ISR aircraft would fit nicely into their approach?

Bitzinger: It would.

They are not in a rush because they have modern F-16s and F-15s but they are already participating in the F-35 program.

SLD: And the F-35B would seem to fit their basing needs well.

Bitzinger: It would. The F35-B certainly gives you more flexibility when it comes to basing.

They only have two air force bases here and additionally have roadway-focused bases. Those are extremely difficult to use because it takes several days to get ready to use. It would help with the dispersed basing approach favored by Singapore.

SLD: How does the Chinese military modernization effort and Chinese policy in the region shape Singapore’s and others modernization efforts?

Bitzinger: The Chinese are becoming significantly more assertive and more capable at the same time. They are following a path of what I would call “creeping aggressiveness.”

They have become very assertive about their territorial claims in the South China Sea, and their policies have gotten the attention of others in the neighborhood.

Historically, most of the modernization of the military in Southeast Asia has been about power balances in the region. Now it is increasingly about China.

Singapore would like to see multilateral agreements in the region to reduce tensions; but the PRC has evidenced little interest in such an approach.

SLD: How important is an effective US “pivot to the Pacific?”

Bitzinger: Very. But to date, allies in the region are disappointed about what they see as the realities of more rhetoric than reality in US policy.

But make no mistake.

The allies in the region cannot counter China by themselves, and are looking to the United States to play a key role in this effort.

A key element to understand the challenge is that the allies in the region tend to be ground-centric and have limited modernization programs in place for air and naval systems. The real force projection parts of their military, their navies and their air forces are still rather small.

And the idea of a regionally integrated system is years away.

This means that the Chinese are in a good position to pressure, if the United States is not part of the equation.

In the last two years, the United States has been looked upon by a lot of countries in Southeast Asia as we need to have you involved; we need to have you more active in Southeast Asia than ever as a hedge against the Chinese.

SLD: You have been involved for a long time in analyses of the Revolution in Military Affairs. It makes sense that you are in Singapore, because I think they take this effort very seriously.

Bitzinger: They do. For Singapore, the core concept is that of Integrated Knowledge Command and Control.

They see C5ISR as a core force multiplier and an ability to reach out further with their forces, rather than having stovepiped service approaches.

It is a central tenet of their approach, and they clearly at the cutting edge of thinking on this.

And they certainly appreciate the role of the USMC in the region because the USMC is the most integrated of the American forces.

The featured photo shows Singapore Defense Minister Ng Eng Hen inspecting a USAF F-35A during a visit to Luke AFB. Credit Photo: Ministry of Defence, Singapore.