By Robbin Laird

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) shaped a joint force which was able to self-deploy to the Middle East. With the RAAF’s new force package of advanced tanker, the C-17 and Wedgetail, the ADF experienced a joint capability which it had not had before, one which was featured in Middle East operations.

This self-deployment capability was sustained in part by the presence of allied and commercial logistics structures in the region to which it deployed.

But for a regional crisis, facing an adversary with tools to disrupt the base, IT systems, and parts supply chain, how will logistics be sustained through the duration of a crisis?

In Thomas Kane’s well-known study of military logistics, the author coined the phrase, “logistical capabilities are the arbiter of opportunity.” Armies which have secured reliable resources of supply have a great advantage in determining the time and manner in which engagements take place. Often, they can fight in ways their opponents cannot.

One of the key speakers at the Williams Foundation Seminar on April 11, 2019, was Lt. Col. Beaumont. Beaumont is an army logistician but one with a focus on joint logistics support.

According to Beaumont: “Logistics will give us options and the flexibility to respond in a crisis as well as defining key constraints on freedom of action.”

In a capitalist society, of course, much that feeds a logistics machine in times of crisis or war is outside of the control of the military and is really about the capability to mobilize resources from the private sector in a timely and effective manner.

In effect, logistics is about taking resources out of the economy and making them available for the battlefield.

According to Beaumont, the main focus of logistics in the recent past has been tactical, but as we face a peer-to-peer environment it is important to take a more strategic perspective.

But the shift facing the militaries of the liberal democracies, can be described as a strategic shift from operating on the basis of “assumption logistics” ordered and delivered by a global just in time supply chain to shaping and operating from an “assured logistics reservoir or flow” in a crisis.

Beaumont highlighted that one cannot assume even if one is operating within a coalition that the coalition partners will be able to sustain you in a crisis.

“A key factor is what the level of mobilization has been achieved before a crisis to sustain a force. There is a long lead time to turn on the spigots from industry, and that is not just in Australia.”

He argued as well that different types of systems being operated across a coalition makes the common sustainment challenges that much more difficult.

He noted that “even in the Middle East, each of the nations that operated there, by and large, provided for their own logistical support and used their own national supply lines.

“And with such an approach, the lift assets in a crisis will be rapidly overwhelmed by demand.

“We saw that in 2003, as we all head to the Gulf, and we effectively dried up lift and tanker forces available for movement of forces.”

He underscored the importance from both a national and coalition perspective of Australia enhancing its sovereign capabilities and options with regard to supplies and logistical support.

“With a sovereign approach, you can become a contributor rather than primarily focusing on how to draw upon a global supply network which will be significantly constrained in a crisis in any case.”

What follows is Lt. Col. Beaumont’s presentation at the Williams Foundation Seminar

Discussions about self-reliance, like many other conversations among defence planners, rarely begin with a conversation on supply and support.

Many of these conversations can end with it.

The ability of a military to conduct operations independent of another’s aid is intrinsically linked to the capacity to move, supply and support that force.

These three factors can be a powerful influence on strategy and strategic policy formulation as they can set significant limits in what the ADF can practically achieve independent of others nor not.

Alternatively, and far less desirably, these three factors can be overlooked and the time at which those limits are confirmed will be when the ADF – if not Australia – can least afford it.

If we are to make a reasonable attempt at confirming how the ADF might sustain self-reliance, let alone consider a scenario where it will face a significant threat in ‘high-intensity’ conflict, a good portion of the discussion will have to be centred on the dry, seemingly bureaucratic and technically dense topic of sustaining military forces.

Today I will talk on how we might sustain self-reliance.

More importantly, I would like to challenge some of the assumptions we make about logistics and discuss some of the problems we are reluctant to truly address.

As a logistician looking outward into a world where strategic competition is particularly evident, I get nervous. As a research student studying the ADF’s approach to its logistics readiness prior to operations, I get nervous. Perhaps, after this presentation, you might feel a little nervous too!

The topic of logistics might seem to be matter for military commanders, being typically defined as the ‘art and science of maintaining and moving forces’ or variations thereof. As nice as that may sound to the military-minded,

I’d like to offer a paraphrased definition coined from Logistics in the national defense, one of a few books on logistics and strategy:

Logistics is a system of activities, capabilities and processes that connect the national economy to the battlefield; the outcome of this process is the establishment of a ‘well’ from which the force draws its combat potential or actual firepower.

Logistics is the connective tissue between the military and the national economy, and is a ‘verb’ as much as it is a ‘noun’. The military can influence economics through logistics demand and requirements, just as the economy shapes capability development and provides the resources that are shaped through the logistics process into combat potential or actual firepower.

A true assessment of self-reliance therefore relies upon our ability to bind ‘the economic’ and ‘the military’ into the same argument.

I proffer that the current debate on the logistics aspects to Australian military self-reliance are hidden in the natural link between it and national defence economics, and are currently coached in monumental terms and framed by enormous problems. National fuel supplies, prioritised sovereign defence industries and national manufacturing capacity, economic resilience in an era of globalisation.

These contemporary, popularised, topics certainly give us pause. They are major national security concerns that are bound to influence our role in the world in a period of major power strategic competition. They have been seemingly unresolvable problems to Australian governments and strategists for decades, beyond the period in which self-reliance was ensconced in the strategic doctrine of the 1970’s, 80’s and 90’s, and to the interwar period where lessons from the First World War reminded them to be prepared for national mobilisation.

They are truly national issues, and will never be solved by Defence, or any other arm of Government, independently.

Nonetheless, niggling doubts and prudence lead us to consider self-reliance yet again.

We are questioning, here, what Australian can reasonably do with its military forces irrespective of whether we are in a coalition or not.

Australia’s military history makes these concerns completely justifiable. Twenty years ago this year we assumed the mantle of coalition leadership in an intervention in East Timor, and operation which exposed the limits of the ADF of the time. We thought we could do it, but – as Cosgrove put it – it was a ‘close run thing.’

But as the Second World War proved, even in a coalition conflict there will be times the ADF will need to ‘go it alone’ and sustain itself as our allies resources are drawn elsewhere.

Who’s to say these scenarios will be unique?

The ADF, its partners in academic, industry and government, are at a point where the discussion has to get to the specifics of the problem.

We have to question ourselves as to how our impressive new capabilities, from the RAAF’s F-35 to the Army’s Combat Reconnaissance Vehicle, can endure on the battlefield of the future when our friends are far away.

The answer can’t afford to be as simplistic as ‘thirty days of supply’ or ‘purchase from the global market.’ We have to delve into the resilience of the national support base, globalised logistics arrangements and our relationships with coalition partners.

I hope that today’s presentation gives you an insight as to where we might want to look, and perhaps suggest at assumptions we may wish to challenge as a nation and military.

Why Logistics Matters Now

Before we go on, I’m going to step back and offer my thoughts as to why logistics matters right now.

With increasing agreement that Australia is party to increased strategic competition, interest in how we might sustain self-reliance is also gaining interest. The line between peace and war has always been blurred, and now Western militaries are starting to act.

In the recently released Joint Concept for Integrated Campaigning, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff argue that the ‘binary conception’ of peace and war is now obsolete, and a ‘competition continuum’ now applies.

The Australian Army would agree if ‘Accelerated Warfare’, an exploratory concept which considers a devolving strategic situation, is any indication. Now these same Western militaries recognise they must act in times other than in armed conflict, offsetting the strengths of other nations or groups who have a very different interpretation of what defines war.

We are witnessing, in this strategic competition, actions of a logistics tone.

The logistics systems which sustain nations and their military forces have always had a ‘deadly life’.

The architecture of global supply chains, siphoning national wealth through geographic areas of immense strategic interest to nations and others, are natural points of strategic interest. ‘Logistics cities’, major trade hubs and economic routes attract the interest of Governments and have become of immense strategic relevance.

All arms of Government can be seen in action, using diplomatic, informational, military and economic means to shape how both commercial and military logistics might be applied to their favour.

Supply chain security continues to occupy our minds as we intermingle our desire for national prosperity through global trade with our desire to prevent the loss of native capacity to build military capability, mobilise and sustain operations.

In this environment it will take little effort for nations to exert influence, or strangle the capacity of a nation to respond to threats militarily.

War won’t always begin when the first shots are fired.

Freedom of action and the ability to respond is clearly being tested.

A recent report by the US Defense Science Bureau written for senior leadership highlights the impacts of strategic competition on the US military’s capacity to protect its strategic interests independently. It examined the threat to US interests from Russia and China as they applied to its capacity to project power.

As these reports tend to go, its conclusions weren’t pretty.

Firstly, it recommended conducting realistic wargames and exercises to reflect threats and the capability of the ‘logistics enterprise’ to respond.

Secondly, it advocated to ‘protect, modernise and leverage’ the mobility ‘triad’ of ‘surface, air and prepositioning’.

Thirdly, it articulated the need to protect logistics data from espionage and manipulation, especially information that was held by national commercial partners.

Finally, it recommended that the US must increase its funding to logistics programs to make anticipated future joint operating concepts viable. Those are significant capability concerns that are equally applicable to the ADF.

They are concerns we could invest our way out of, subject to the scale of our military, and would go a long way to assuring logistics support to our own operations.

Force posture or capability development are important in strategic competition, but the way in which nations mobilise logistics support is equally important. Those nations that aspire to self-reliance naturally invest in policies, plans and national defence industries. Clearly, the degree to which the logistics system continually takes resources from the economy to create military capability varies with political desire and in a way, hopefully, that is commensurate to the threat. In peace this system is generally stable and allow for predictable results.

When uncertainty becomes prevalent, or a crisis begins, this logistics system must be altered to direct economic and logistics resources to where they are most required.

Creating surety in logistics is incredibly important.

And so, in recent years, we’ve seen Australian defence industry policy renewed alongside strategic policy, we’ve seen the Services develop close and valuable ties with industry partners, and we’ve seen a commitment to sovereign defence industries. Only time will tell whether Australia has invested enough attention to mobilisation to prepare the nation for a time of significant crisis. I suspect we haven’t considered it enough.

We might be beginning a conversation on the military link to industry, but it’s pretty clear that other nations are in an advanced state.

For example, Western Governments – especially the US – are highly concerned with the emerging Chinese policy of ‘civil-military fusion’. This approach is seeing tighter integration between industry and the PLA, thereby improving the seeping of ‘dual-use’ technologies into military practice.

With industry is moving to the centre of geopolitics, we’re starting to see whole-of-nation efforts shaping how militaries are formed and act operationally.

That this Chinese political philosophy makes the US nervous shows how significant economics and logistics are in strategic competition.

Managed properly, the logistics process can translate what industry provides into tactical combat potential and reflects a national capacity to compete, deter, and to demonstrate an ability to militarily respond.

Therefore, the presence of robust industry policy, the organisation of strategic logistics capability to leverage these arrangements, the appointment of commanders to oversee sustainment and the presence of mobilisation plans and doctrine, are good indicators of future military success.

These are not areas we typically look at when we consider how belligerents may compete, but they can be discriminating factors in any strategic competition.

Other examples of logistics influences on strategic competition are before us if we choose to look. One nation might overcome force projection challenges by building an island where there was none before, while another will procure air mobility platforms or ships for afloat support.

Others will examine force posture from first principles, while another will establish arrangements and agreements that might support a friendly force based in a partner nation at short notice.

Militaries might be restructured so that the acquisition and sustainment of capability improves preparedness, or eventual operational performance, more effectively. Just as there will be an unending competition in the development offensive and defensive capabilities between nations, so too will there be unending shifts in the way military forces will offset one another through logistic means.

At the height of non-armed competition, these changes in logistics systems will manifest in mobilisation.

Logistics has long been regarded as a crucial component of military capability, and the supply and support given to armed forces a major constituent of operational success. Logistics constraints and strengths can shape strategy, determine the form and means of operations, and if given nothing more than a passing glance by military commanders and civilian planners, will prevent combat forces from ever achieving their full potential in the air, and on the sea and land.

As we seek to answer the question, ‘what can we achieve on our own?’, a really difficult question to answer, solutions to our logistics problems and concerns must be front and centre. A suborned view of logistics in this discussion about self-reliance is way out of step with the strategic reality facing the ADF.

In engaging with this reality we might see that logistics is, in fact, a strategic capability in its own right.

Logistics in the ADF – How Might We make Ourselves More Self-reliant?

How does the ADF employ its strategic logistics capability to create a strategic advantage, and to improve its ability to operate without the intervention of coalition partners?

Firstly, we must recognise that it is one thing to have the weapons of war on hand; if those capabilities are to have any use whatsoever, they must be complemented by the logistics resources necessary that they be used at their desired potential.

An investment in logistics is an investment in combat power. At a simplistic level many of our weapons, ammunition and components are acquired from other nations, or as we see with major capital programs, produced with others. Without these supplies, the technology at the ADF’s disposal is fundamentally worthless.

We complement our forces – in all domains – with discrete logistics capabilities on offer from partners that we cannot generate independently. Even in those times where the mantle of coalition leadership has fallen upon the ADF’s shoulders, as we saw with regional peacemaking and keeping operations of the last twenty years, the ADF has been supported from other quarters.

Secondly, the ADF’s engagement with industry must reflect the needs of higher states of readiness and surety of support.

It is incredibly difficult to determine how self-reliant the ADF might be when the present practice of global production and supply masks supply chain risks, and while Australia lacks the levers or market power to directly intervene in global production. Reliability is in question; this is not a fault of industry, but a consequence of the complex, decentralised, industry environment that works well in peacetime.

The ADF must emphasis reliability in its logistics – to deliver ‘assured logistics’ – for wont of a better term. It must also encourage industry to be ready to match short-notice, strategic, responses. It may be that in a time of crisis traditional boundaries such as intellectual property rights will need to be challenged, industry capacity seconded to defence interests, and projects redirected in new directions at very short notice.

At the very least ADF and industry should discuss how industry ‘scales’ in parallel with any expansion of the fielded force.

Thirdly, the ADF should leverage existing command arrangements to better coordinate logistics across the organisation.

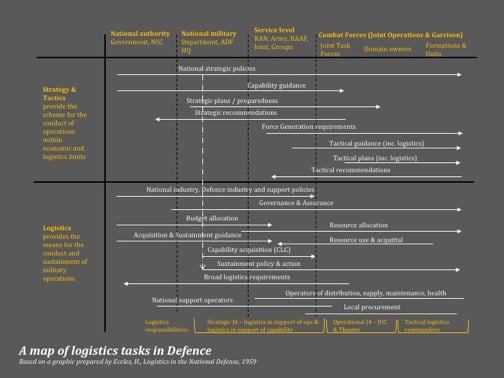

It’s impossible to talk about coordinating Defence logistics activities without commenting on the nature of strategic logistics control in the Defence organisation.

Because logistics problems are naturally large, the ways in which concerns on self-reliance will be addressed will invariably be pan-organisational in nature. Commander Joint Logistics Command might be the CDF’s ‘strategic J4’ or key logistics commander, but he or she partners with the Capability, Acquisition and Sustainment Group, Estate and Infrastructure Group, the Services and others within what’s called the ‘Defence Logistics Enterprise’.

Each organisation naturally has a different perspective as to what ‘self-reliance’ means, and there is always a risk that Defence will have difficulty identifying where its logistics risks and opportunities truly lie in this context. Quite clearly the analysis of what the ADF’s ‘logistics limits’ are, and what national resources might be needed, requires a coherent effort with solutions achieved through mutually supporting activities conducted across the organisation.

This may mean we reinvigorate the idea of ‘national support’as a collective process in which industry and the military can work together to support operations; where national industry support to military operations is included at a conceptual level.

Fourthly, the ADF must look to address noteworthy operational capability gaps.

The strategic level challenges to self-reliance might fundamentally shape whether the ADF will perform in the way intended.

What about the condition of the forces in the operational area?

The most significant operational-level challenge to self-reliance, I argue, is with respect to strategic mobility. The ADF regularly seeks operational-level support in terms of intelligence and a wide range of capabilities that a military of our size simply could not realistically produce.

Perhaps there will be a time in which very long-distance fires will overcome the geography between us and an adversary, but until they do to a level that satisfies the desired military outcome strategic mobility capabilities will be continue to be critical to anything the ADF does.

Our strategic mobility will be critical to achieving a persistent response (whether that be on land or at sea) to an offshore threat.

Most of our partners declare their own paucity in strategic mobility capacity which suggests that even if our future conflicts are shared, we might still need to invest heavily in order to meet our own requirements.

On top of the mobility capabilities themselves, the aircraft and the ships and the contracted support we can muster from the nation, we cannot forget the ‘small’ enablers that support a deployed force.

In our recent campaigns in the Middle-east, we have been heavily dependent upon our coalition partners for the subsistence of our forces.

There is a real risk that our operational habits may have created false expectations of the logistics risk resident within the ADF, especially when it comes to conducting operations without coalition support.

As the Services look to their future force structure, it will serve them well to scrutinise not only those capabilities essential for basic standards of life, but the wide spread of logistics capabilities which are essential complements to their major platforms.

These include over-the-shore logistics capabilities for amphibious operations, expeditionary base capabilities as well those elements of the force that receive, integrate and onforward soldiers, sailors and airmen and women into the operational area.

With the newly formed Joint Capabilities Group, the ADF has a significant opportunity to comprehensively address these operational challenges to self-reliance.

Logistics and a Way Forward

You don’t have to deeply analyse defence logistics to understand that self-reliance is underpinned by the ADF’s – if not the nations – capacity to sustain and support its operations. The comments here are certainly not revelatory, nor are the allusions to the limits of ADF’s capability particularly surprising.

For the ADF to be effective in high-intensity conflict there is still a way to go yet, irrespective of whether it goes to way within a coalition or not.

There is every chance that even if the ADF does deploy as part of a coalition, it will still be necessary for it to have a capacity to support itself.

It is understandably important that we have a conversation about the limits to self-reliance in the current time of peace and think deeply about establishing the policy infrastructure and organisational arrangements that will enable us to make good judgements on what the ADF can or can’t do alone. Without doing so we risk logistics capability being revealed as a constraint on ADF operations, not a source of opportunity and the well from which the joint force draws its strength to fight.

If we are all serious about self-reliance, we must be serious and frank about the logistics limits of the armed forces, and the industry capacity of the nation. I’ve made some suggestions in this brief talk.

However, let’s continue the discussion by challenging some of the assumptions that we hold about logistics; that a coalition will underwrite our logistics operations, that the global market – designed for commerce not war – can offer us the surety of support we require, that we will have access to strategic mobility forces that even our allies believe they are insufficient in.

No matter what type of war, there will be some things we must re-learn to do on our own. I am sure we can all here challenge ourselves and our beliefs – whether we are confident in these beliefs in the first place.

If we do not, it is inevitable that we will compromise the plans and policies we create, if not the logistics process more broadly.

Moreover, any neglect prevents us from minimising the ADF’s possible weakness with sources of strength or comparative advantage.

Present day convenience will likely cost the future ADF dearly. In fact, we may find that it is better that Australia has an ADF that can sustain, and therefore operate, some capabilities incredibly well at short notice rather than aspiring to a military that spreads its logistics resources across areas where the prospects of success are much lower.

Whatever we do choose to do, it will be important to bring defence industry alongside the ADF as the partnership between the two truly determines what is practical in any war, and not just one in which ‘self-reliance’ is on the cards.