During my recent visit to Australia, a major focus of attention was upon the challenge facing the Australian Defence Force to sustain that force through a crisis period if a peer competitor was involved.

And one of the speakers highlighted the significant challenge of moving beyond the Middle Eastern mindset whereby the logistical system has been set up to support slo-mo conflict, not high-intensity conflict.

“We need to move beyond our current Middle Eastern logistics mindset.”

“If we are honest with ourselves, the threats were asymmetric and we operated far from our domestic basses.

“What took place in the Middle East was a sustained buildup of logistics support structures in the Middle East prior to operations.

‘These hubs became part of a network that could be called upon to support a range of operations amd were underwritten by significant commercial and host nation support.”

So how is the US doing in this regard?

With the very significant readiness shortfalls generated over the past decade by defense funding and significant global deployments, it was clear that the US forces faced a significant readiness shortfall, or, in my view a crisis, when President Trump came to power.

Although funding has been generated to start the repair process, the basic system remains the same, one, which is not designed to provide for parts to support the globally deployed force, or to provide for a buffer in parts availability.

The system is designed to provide for taut supply chains, just in time delivery via Fed Ex or DHL (with the customs choke points which slow down delivery), and a hording of parts in CONUS, which means that parts then have to flow from the US as a supply hub, not from a robust global set of supply centers which can provide support to the point of interest or attack globally.

A good case in point is the unique USMC creation, the Special Forces MAGTF.

We were present at the creation of the SP-MAGTF more than a decade ago.

The Osprey and its capabilities and the necessary KC-130J support to go with the Ospreys generated this unique creation.

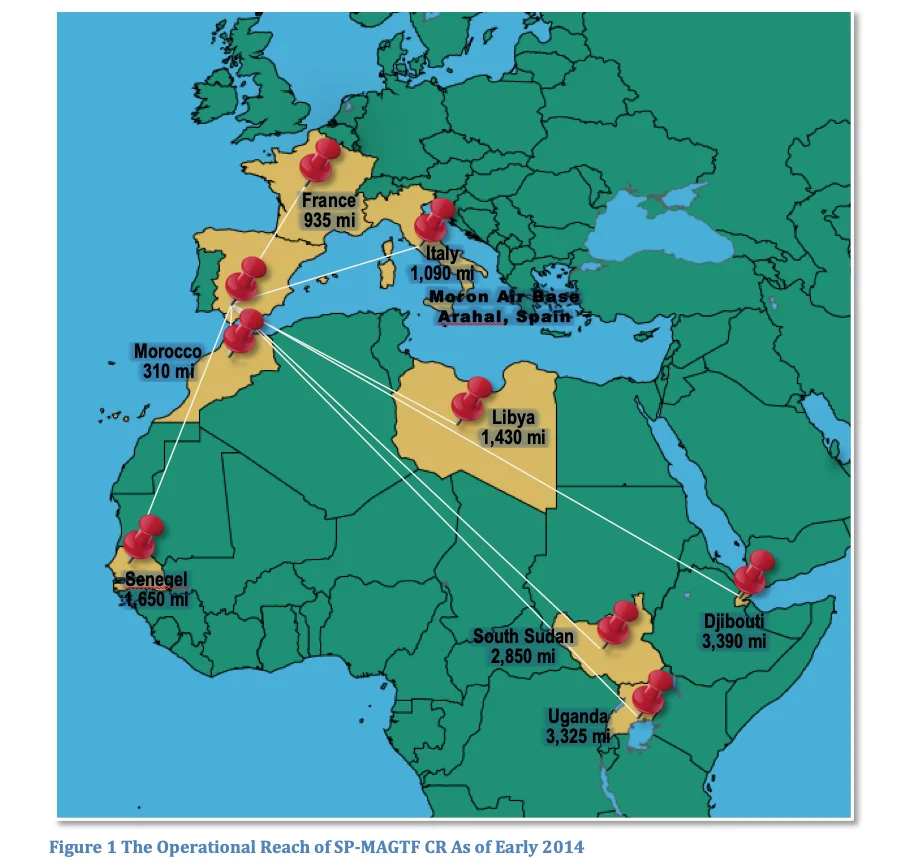

The speed and range of the Ospreys opened up new opportunities to provide for crisis support throughout Africa, which was the focus of the effort.

I recently had the chance to discuss the logistics challenges facing the force with the CO of VMM-266, Lt. Col. Brandon Whitfield. As a crisis response force, in my mind, this provides a case study of what a broader challenge crisis management will provide for testing the current logistical system.

Lt. Col. Whitfield has recently returned from Europe where he commanded an SP-MAGTF. Even though the force has been in existence for more than 10 years, this “experiment” already has significant operational experience.

The SP-MAGTF has grown to include more KC-130Js and Ospreys, in part to ensure aircraft availability. The force has really no permanent home even though they operate from Naval Air Station Sigonella and Moran Airbases.

“We have only three MV-22 spots and two KC-130J spots at Sigonella although we currently operate six MV-22s and three KC-130Js.”

But the aircraft availability measure is undercut by the absence of dedicated logistical support to SP-MAGTF and to the need to reach back to CONUS to get a number of parts necessary to operate the force; in shall we dare say it, a crisis.

“A number of high demand parts are not on the shelf. These parts are normally spread out across CONUS and it takes 12 days or so to order parts and get them flown by FEDEX or DHL to me in Europe.”

Put in blunt terms, the logistical footprint for the force is not optimized for the force and its operational needs.

It is a question of the need for proper global hubs and a supply chain better tied to operational realities, than the performance indicators for a supply system, which is not really geared to those realities.

And the threat of the cloture of the base at Sigonella still hangs over the forces, which depend upon support from that base.

The availability of aircraft piece obviously impacts on training, because one can not compromise operational availability of aircraft for a mission, while using those aircraft for training. So logistical shortfalls directly impact on training, and both are key drivers of operational readiness and aircraft availability.

In my perspective, and I am not suggesting the CO said this, the logistical system as currently constructed is a significant strategic vulnerability which have constructed ourselves and needs to be addressed in those terms.

We need to combine hubs globally located and fully capable of logistical support to a crisis force with enough “buffer” to endure a crisis, and with enough protection to endure non-kinetic and kinetic attacks.

This is not a nice to have capability; it is an essential strategic capability of we are to compete effectively in 21stcentury conflicts of the sort envisaged in the new national security strategy.

For three articles which highlight the standup and evolution of SP-MAGTF, see the following:

A Look Back at the Standup of the SPMAGTF-CR-AF and the Way Ahead on Crisis Management: A Look Back and Forward with Col. David Suggs, CO of MCAS Yuma

By Robbin Laird

During my May 2018 visit to MCAS Yuma, I had a chance to sit down with the Commanding Officer of the Air Station who has significant electronic warfare experience and was part of the standup of the SPMAGTF-CR-AF.

The naming convention was changed multiple times.

The original name was SPMAGTF-AF operating out of NAS Sigonella, Italy.

This force was not a CR force and was designed to support Theater Security Cooperation (TSC) utilizing logistics combat element (LCE), no Air Combat Element (ACE), or Ground Combat Element (GCE).

The (CE) was limited in scope and tailored to meet mission requirements.

After 2013 the ACE, and GCE were added with a robust CE to support the Crisis Response (CR) mission requirements and hence became the SPMAGTF-CR.

We are focusing on the role of insertion forces in 21stcrisis management and the birthing of the SPMAGTF-CR-AF &CENT is clearly part of that transition.

Our conversation focused around the standup of SPMAGTF-CR-AF and the way ahead with crisis management.

During the visit of Murielle Delaporte to Morón Air Base, Spain, Dec. 6, 2013, the initial standup of the SPMAGTF-CR-AF was described:

SPMAGTF–CR-AF is a self-command and -controlled, self-deploying and highly mobile maritime crisis response force allocated to U.S. Africa Command to respond to a broad range of military operations to provide limited-defense crisis response in the AFRICOM/EUCOM region.

The Marine task force can serve as the lead element, or the coordination node, for a larger fly-in element. It also can conduct military-to-military training exercises throughout the AFRICOM and EUCOM areas of responsibility.

Like other MAGTFs, the SPMAGTF–CR includes a command element, a ground combat element (GCE), an aviation combat element (ACE) and a logistics combat element (LCE). It is composed largely from II Marine Expeditionary Force, Camp Lejeune, N.C., coordinating a balanced team of ground, air and logistics assets under a central command.

https://www.mca-marines.org/leatherneck/2014/04/filling-gap

Col. Suggs provided an overview on how the standup and operation of the force provided a defensive insertion force, which empowered crisis response options but also triggered broader working relationships with allies in shaping convergent crisis response capabilities.

Crisis management requires both the forces and the convergent C2 and decision making to use those forces. And the standup and operation of the SPMAGTF-CR-AF facilitated both processes.

In effect, the formation of the SPMAGTF-CR-AF provided a bridging function for AFRICOM and EUCOM to be able to provide insertion forces able to deploy rapidly, a key means for triggering enhanced training with key allies in the Western Mediterranean.

This was especially important as the focus had shifted dramatically to CENTCOM and provided an important stimulus to American forces being able to work through with interoperability among crisis response forces.

SIPRNET is where Americans work with each other, and can become a limiting capability which inhibits broader and more effective collaboration with allies, the kind of collaboration central to allied crisis management.

And the Western Med collaboration in turn provided leverage back into broader NATO collaboration.

And all of this was driven by the stand up of the SPMAGTF-CR-AF as a forcing function force, so to speak.

“In fact, SPMAGTF-CR-AF itself was born from the Benghazi crisis.

“We did not have a reactive/sustainable force to operate in Africa and the AFRICOM and EUCOM relationship did not have in place the procedures for how to transfer forces from one component commander to the other in African operations in a timely manner.

“Having a complete understanding and the authority to launch a CR force from a sovereign nation can create additional bureaucratic delays if all participates are not on the same sheet.

“SPMAGTF-CR-AF created a catalyst and through collaboration with the Spanish and Italian MODs we were able to establish a clear common understanding allowing for quick response to a crisis.

“To me a crisis is my house on fire and I need to call the first responders right away and know the number to call. It’s about building connective tissue, or access to the right people at the right time.”

“We needed to set up the first responders and the 911 number.

“And it is not just a question of the physical force, but the working relationships among allies to allow that force to engage rapidly.

“We have logistics support units postured in Africa but we are not set up to operate in Africa for a sustained period of time unless we are operating out of Djibouti.

“And it was cost prohibitive to set up Djibouti West, if one might call it that.

Question: In effect, you were sizing a force that could be effective, but clearly defensive in nature, and one that could work with allies to get not just pre-positioning but de facto pre authorization for use?

Col. Suggs: The challenge was precisely that.

“SPMAGTF-CR-AF was set up to operate out of Morón Air Base, Spain, and worked closely with Naval Air Station (NAS), Sigonella, Italy.

“The Spanish have great forces operating from Morón Air Base and we had close proximity with the French.

“We have had a lot of coordination with French Forces and conducted routine training exercises to ensure proper techniques and procedures where established.

“We have introduced the Osprey to the Spanish, French, Italians, and UK, integrating forces conducting amphibious training on their ships. This increased readiness in not only our forces, but also to NATO forces.

“In effect, we were going back to the time when we used to have a MEU in the Mediterranean working with allies, but that has atrophied given the focus on CENTCOM.”

Col. Suggs highlighted that the SPMAGTF-CR-AF was a triggering for more allied cooperation as well.

“We created a number of second and third order effects as well as our small force contingents were able to work with other NATO allies, such as in theEUCOM Black Sea Rotational Force.

“There a small force of Marines led by a Marine Corps LtCol led the effort and we learned how to work more effectively together.

“The problem on the US side is that we rely primarily on SIPRNET for our communications and even though a significant amount of the content is actually unclassified, we are operating within our SIPRNET culture.

“Allies are not on SIPRNET so we need to train ourselves to become more interoperable and work with other communication and intelligence channels to deliver the kind of crisis management effect we are going to need.”

“This small little group is operating as a trigger for significant reworking by ourselves and our allies, way beyond the combat weight of what that force brings to the table.”

Question: It is important to focus on crisis management, not simply forces the US can deploy to an event.

How does your SPMAGTF experience trigger that kind of learning?

Col. Suggs: If we have a crisis to respond too, a key part of the response is ensuring that the relevant allies are all on the same page operationally and politically.

“Because we are training regularly with those allies but not bringing overwhelming force to the training, we shape common approaches and procedures, which are crucial to crisis management situations.

“It is about convergent forces, and convergent intervention approaches and shaping a capability to do so in the short time span which effective crisis intervention requires.

“It is not about bringing multiple Army battalions or Air Force Air Wings. It is about arriving at the right time; the right place and to get the right effect our outcome.

“When one’s house is on fire you want to call the first responders and expect them to show up.

“You are not calling the insurance adjuster’s first.”

Special Purpose MAGTF-CR: The Juba Operation

2014-04-22 By Murielle Delaporte

In a recent article published in Leatherneck, Murielle Delaporte provided an overview of the Crisis Response unit with a focus on the effort in South Sudan. Interviews conducted in December 2013 at the Morón de la Frontera Air Force Base in Spain, where the SPMAGTF–CR temporarily has been deployed since April 2013.

In the following excerpt taken from the article, the author discusses the Juba Operation.

According to the Commanding Officer of the SP-MAGTF-CR in December 2013, Col. Scott Benedict:

“This force provides new capabilities where there has been a gap,” said Col Benedict.

Historically, we would provide this kind of capability of a Marine expeditionary unit [MEU], i.e., the Marine forces that are on ships.

Where there have been some gaps in the coverage of these ships, the Marine Corps created this force and intends to create others like it in order to fill those gaps.

So in that sense, it is a new capability, but the skills that we bring as a SPMAGTF are the same types of skills that Marines have always brought to the fight. In terms of comparing what we are doing now with what we have been doing in the past, my experience over the years has been that this is more the type of missions that Marines have done historically…..

However, what we have historically done is operate small units like this and provide very flexible and agile capabilities to respond to crisis. We have done it for years off amphibious shipping, and now we do it with the extended range capability of the V-22 which allows us to provide some very similar capabilities over the vast areas that we are responsible for.

The ACE commander, LtCol Freeland, who has been trained as both a CH-46 and a MV-22 pilot, said there is a paradigm shift due to the juxtaposition of the expeditionary vertical-landing capability of the V-22—especially useful if a runway or an airfield is not available or if it is necessary to land near the target—and the long legs brought by the KC-130J is able to generate on the theater.

“Both the MV-22 and KC-130J have worked together before in the past, but the way we are teaming them here is a little different: I think one of the best analogies is the tank-infantry team concept,” said Freeland.

We now share the whole mission together: It is shared mission management, shared functional responsibilities within the same flight.

Such a change is not overly difficult, but it is different, and we are expanding tactics, techniques and procedures to leverage the unique capabilities of each airframe.

You have, on the one hand, one V-22 aircraft going a distance, a good one but nothing incredible—let’s say 350 miles—and land vertically anywhere, and you have, on the other hand, one KC-130J which can fly thousands of miles, but [has] to land on a runway.

Now you put the two of them together, and you can take this team thousands of miles away and land anywhere.

This is a very significant paradigm change.

We bring agility and task organize the Ground Combat Element to go anywhere we need to quickly.

“The work we have been doing traditionally in Africa has been done off amphibious shipping,” Col Benedict added.

We would send a ship up and down the coast, and we would operate.

So, this is the same idea that we would not have a permanent presence, but different aircraft.

The capability that we have now is unique, as this pairing of the MV-22 and the KC-130J gives us the type of ranges that is necessary to be able to operate in Southern Europe, while still being able to reach all the operational areas that are necessary in Africa.

That is what I meant by bringing together the old and the new, because when the Marine Corps was envisioning bringing the V-22 forward as a capability, we envisioned this kind of distance to employ the force.

We just have not been [until now] in a position to take advantage or to have to use that capability.

In this particular mission and with this particular force in the area we are responsible for, we are employing the V-22, the KC-130J and a task-organized ground force at the distances we envisioned when this aircraft was designed.

That is revolutionary.

The Marines also are going back to some geographic roots as well, since they have had a long history in West Africa during the Cold War and in the ’90s and early 2000s.

Benedict added,

Well before the current ‘post 9/11,’ it has been episodic because we do exercises and theater security cooperation where we partner with nations, so we learn from them and they learn from us, keeping in mind that we might work together in the future for a common goal.

However, we have not based there.

We have been doing these operations for years, and it has paid dividends when we had to do ‘provide support’ for different countries on the continent.

Another MAGTF, called SPMAGTF Africa, is, in fact, more dedicated to training and partnering with African forces and has been building those relationships for several years on the continent.

This long-lasting effort has proven an essential part in the success of the recent evacuation of U.S. and non-U.S. citizens from South Sudan, with the ability to rely on neighboring partners such as Uganda, which at the time of the crisis actually was involved in a pre-planned small logistics exercise with SPMAGTF Africa, while USAFRICOM also was overseeing an aircraft mission flying 850 Burundians as peacekeepers in Central Africa.

Juba, South Sudan, also has been a case in point demonstrating the revolutionary capability of the pairing between the MV-22B and the KC-130J with the longest-range insert ever accomplished by the SPMAGTF–CR.

As the domestic situation worsened in South Sudan on Dec. 15, 2013, a decision was made to evacuate part of the personnel from the U.S. Embassy in Juba. The mission was given to USAFRICOM, which assigned its execution to the Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa based in Djibouti. It was under the authority of the CJTF-HOA commander, Brigadier General Terry Ferrel, USA, that on Dec. 22, 2013, SPMAGTF–CR repositioned about a third of its force—160 Marines and sailors—from Morón de la Frontera to Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti.

Approximately 12 hours later, a platoon-size element (about a third of that very force) was flown by a KC-130J to Entebbe, Uganda, in order to be better postured to support operations at the U.S. Embassy in Juba.

“Within 60 hours of receiving the execution order, SPMAGTF–CR inserted forces more than 4,000 nautical miles from Spain to Djibouti, Uganda and South Sudan,” said Capt Sharon Hyland, SPMAGTF–CR public affairs officer.

“The distance from Spain to Djibouti is equivalent to a flight from Anchorage, Alaska, to Miami, Florida. This was the longest-range insert to date for this force and was a testament to the organic aviation assets and our task organized force which enables us to accomplish our mission.”

On Jan. 3, 2014, a squad-size element of Marines from SPMAGTF–CR successfully evacuated more than 20 personnel from the U.S. Embassy in Juba, via a KC-130J in coordination with the East African Reaction Force (EARF).

For the full article please go to the Leatherneck website:

https://www.mca-marines.org/leatherneck/2014/04/filling-gap

It should be noted that there are currently three Special Purpose MAGTFs currently, not all operating with the KC-130J and Osprey combinations, in part due to limitation of numbers of assets.

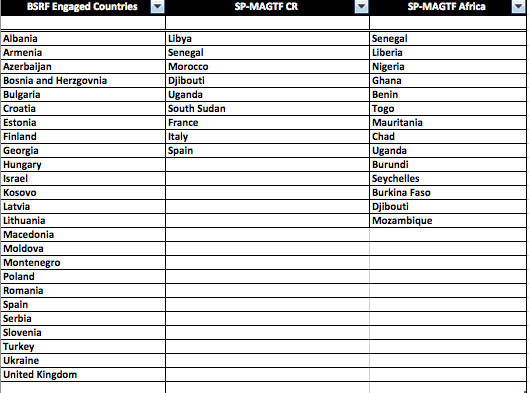

The three are the Black Sea Rotational Force (BSRF), SP-MAGTF CR described above and SP-MAGTF Africa.

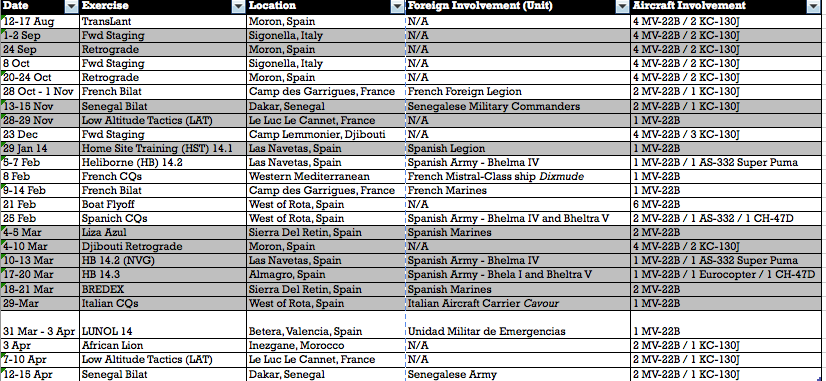

The deployments for operations, training or exercises by the three SP-MAGTFs through mid-April 2014 can be seen in the table below and in the next table the aircraft used in the various deployments of SP-MAGTF-CR are identified as well.

Aircraft used by SP-MAGTF CR Through Mid-April 2014. Credit: USMC

The Osprey and Innovation: Breaking the Mold

2013-08-05 Secretary Wynne recently underscored that with the Osprey, “the Marines are busily embracing the 21st century operational concept.”

During this year’s visit to New River, discussions with Col. Seymour, the CO of MAG 26 and with Major Frank “Robo” Rhobotham, VMM-364 Remain Behind Element (RBE) Officer in Charge (OIC), underscored how significant the Osprey has been in forcing culture change in the USMC and shaping new combat approaches.

The Seymour interview will be published shortly, but in this discussion with Rhobotham, two key aspects of change were discussed.

The first involved the standpoint of the Special Purpose MAGTF, now in Spain, and the second the changing approaches associated with a younger generation of maintainers, who work on the Osprey.

Rhobotham discussed the very short period from the generation of the concept of the Special Purpose MAGTF to its execution. It took about eight months from inception to deployment.

He emphasized the flexibility of the force and its light footprint. “With a six-ship Osprey force supported by three C-130s we can move it as needed. The three C-130s are carrying all the support equipment to operate the force as well.”

The flexibility, which the Osprey now offers Combatant Commanders and US defense officials, is a major strategic and tactical tool for the kind of global reality the US now faces, requiring rapid support and insertion of force.

SLD: Could you describe the process as seen from your end?

Major Rhobotham: We received a request to look at the deployment of a 6-ship detachment of Ospreys to operate flexibly as a group. That started a long, long conversation because it depends on what you want to do with those six airplanes.

Are we going austere, are we working from a prepared zone; are we going to fly 100 hours a month, or are we going to fly 500 hours a month? And where are we going to operate it for environment matters to the performance and endurance of the aircraft?

It is similar to thinking about ground transportation and what car you would used.

Take the Baja 500, for example. If you buy a truck from the Ford dealership, and you drive it around LA, you’re going to get 150,000 miles out of it. You take that same truck and you attempt to run the Baja 500, you won’t make it past the first day.

It is the same thing with this aircraft. If I go from paved runway to paved runway and I fly in airplane mode the entire way, I’m going to get a lot more use out of it. And if I’m flying it like a helicopter and I’m landing in nasty, dusty, dirty environments, it’s going to break down, as any mechanical device will do in that environment.

Additional questions had to be answered.

Where are we going? What are we going to do, how much are we going to fly? Who are we supporting, how are we being supported?

We then got a response back that Africom was interested in what a six-plane V-22 force would look like. With the Africom focus that shrunk the bubble down. The continent of Africa has about every single environment out there.

Mali happens in the middle of this. While we were not told that Mali was even in the play, it was dominating the news in the time period that we began the planning. We really started looking at the western coast of Northern Africa, we looked at the Northern portion of Africa, and obviously Libya is all fresh in everybody’s memory.

We’re an assault support unit; we are always supporting, and we’re supporting the Marines. So obviously, we, by ourselves, are not a force. We enable somebody else to be a more efficient, more effective force.

And that also helps as well in thinking about the deployment focus.

What can we do with the company, how can we help a company? And we fell back upon our MEU mission sets. If we’re going to be supporting the African countries with a company, we draw upon what we know.

We were given some restraints to the diplomatic clearances with our European partners, which shaped the force to a certain degree. And then there’s always the what-ifs.

As a result, we deployed out relatively heavy. We’re running two ships of maintenance in the field, and we have round the clock maintenance.

SLD: Obviously the light footprint of the force gives it significant operational flexibility.

Major Rhobotham: That is a significant benefit. If for some reason, due to political turmoil in any of those countries, it doesn’t take much to completely pack up and move.

And it helps that the Osprey has a refueling probe. We’re no longer limited to how far the ship is willing to steam in one day. Now we’re limited to how much can that tanker hold?

And we can put the Marines in the back and tank, and as long as I’ve got a C-130 that’s willing to go with me and has something to give me, it’s human limited now. How many hours can I fly this airplane before I’m too fatigued?

SLD: The Marines deployed the SP MAGTF in April?

Major Rhobotham: It was deployed in April and it actually self-deployed. The V-22s flew across the Atlantic, and although it has been done before, this is a new operational reality which folks need to recognize exists. We got all the airplanes where they needed to go flying there, and not being airlifted by the USAF.

SLD: You are preparing to shift out a new group of Marines to replace the currently deployed SP-MAGTF, I believe?

Major Rhobotham: That is correct. The Marines from 365 will return, and the Marines from 162 will go out. And right now, it’s scheduled to be the same package. It is scheduled to be the same number of marines, and the same number of aircraft.

SLD: In your view how is the SP-MAGTF different from a MEU?

Major Rhobotham: It compliments a MEU very, very well. It is a different tool set. It is similar to having both a screwdriver and you’ve got a drill in your toolbox; that drill is a lot like the MEU. It’s a lot more powerful, it can go a lot faster; it can do a little bit more powerful things. But it doesn’t mean you need to throw away your screwdriver.

The SP-MAGTF has a lighter footprint, and we can go to any place that the government sees that needs a little bit of attention; we can drop one of these special purpose MGTFs off.

We can just go wherever we need to, drop it off, and then when that situation’s resolved itself or reached some sort of threshold that we feel comfortable, we can pick this up and move it anywhere we want to.

In the past we would have to fly in infrastructure or move by ship; establish the infrastructure and the diplomatic agreements to place the infrastructure in country. Now I can fly in the force; stay until I wish or need to depart.

A special purpose MGTF is not to replace a MEU; it is to compliment a MEU. And while there are separate commands, they’re not led by the same colonel, they’re designed to complement each other, not to replace each other or be lieu of each other.

And I think that’s probably a point that doesn’t get made enough.

SLD: The other major cultural change with which the Osprey is associated which you mentioned earlier has been the rise of a new generation of maintainers able to handle the complexity of maintaining something like the Osprey.

Major Rhobotham: A major change which I have experienced, but really is not talked about is the role of the new generation and their ability to process information and combat learning.

The new genreation grew up with such an influx of information that they are able to process information in ways that are a challenge for me, and for my parent’s generation are impossible.

And it makes them amazing mechanics.

My Marines downstairs can flip through publications and can resource four or five different sources of information and come up with amazingly creative solutions to problems.

When I grew up, you would go to the library, you’d grab the encyclopedia, you’d get the first cut from the encyclopedia, you’d then grab two or three references, beyond that you’d support your theory, your statement, your thesis, whatever it was.

For this generation, they are very used to opening up a source and saying well, I can’t prove that this information that was published by so-and-so on this website’s true. And they’ll grab something 180 out, cross-reference it and make an assessment, and that is a significant capability for troubleshooting.

We have items that don’t always fail the same way every day. For example, I’m getting an indication in the cockpit of a certain failure, and these new mechanics can go through one publication, and it will indicate that they are to test this wire, or that wire, and if those pass, change the sensor, and then after that, you call an engineer.

And these young men and women are incredibly creative.

They will look at a different publication that was talking about a similar sensor in a different part of the aircraft, it has these three other steps. Why aren’t these three steps in here?

And then, the next thing you know, they have built procedures that we then write into the process.

I attribute it to the way their brains and the way they’re socially trained even from a young age to look at information and not necessarily believe that just because it’s written in a book it’s the end all, be all.

This thinking process is crucial, especially with an airplane that’s complicated as the V-22.

SPMAGTFCRThe featured photo shows crew members conducting final inspections on an MV-22B Osprey with Special-Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force Crisis Response prior to departure, July 26, 2014. The Department of State, in coordination with the U.S. Ambassador for Libya, requested Department of Defense support for a military-assisted departure of embassy personnel. SP-MAGTF Crisis Response is a self-deploying, self-sustaining task force with the capacity to provide a rapid-response capability to U.S. Africa Command. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by 1st Lt. Maida Kalic)

And the video below shows an even younger Captain Whitfield in Afghanistan.

The video was posted on August 15, 2008 and is credited to the 24th MEU.