By Kenneth Maxwell

Social and Racial Divisions

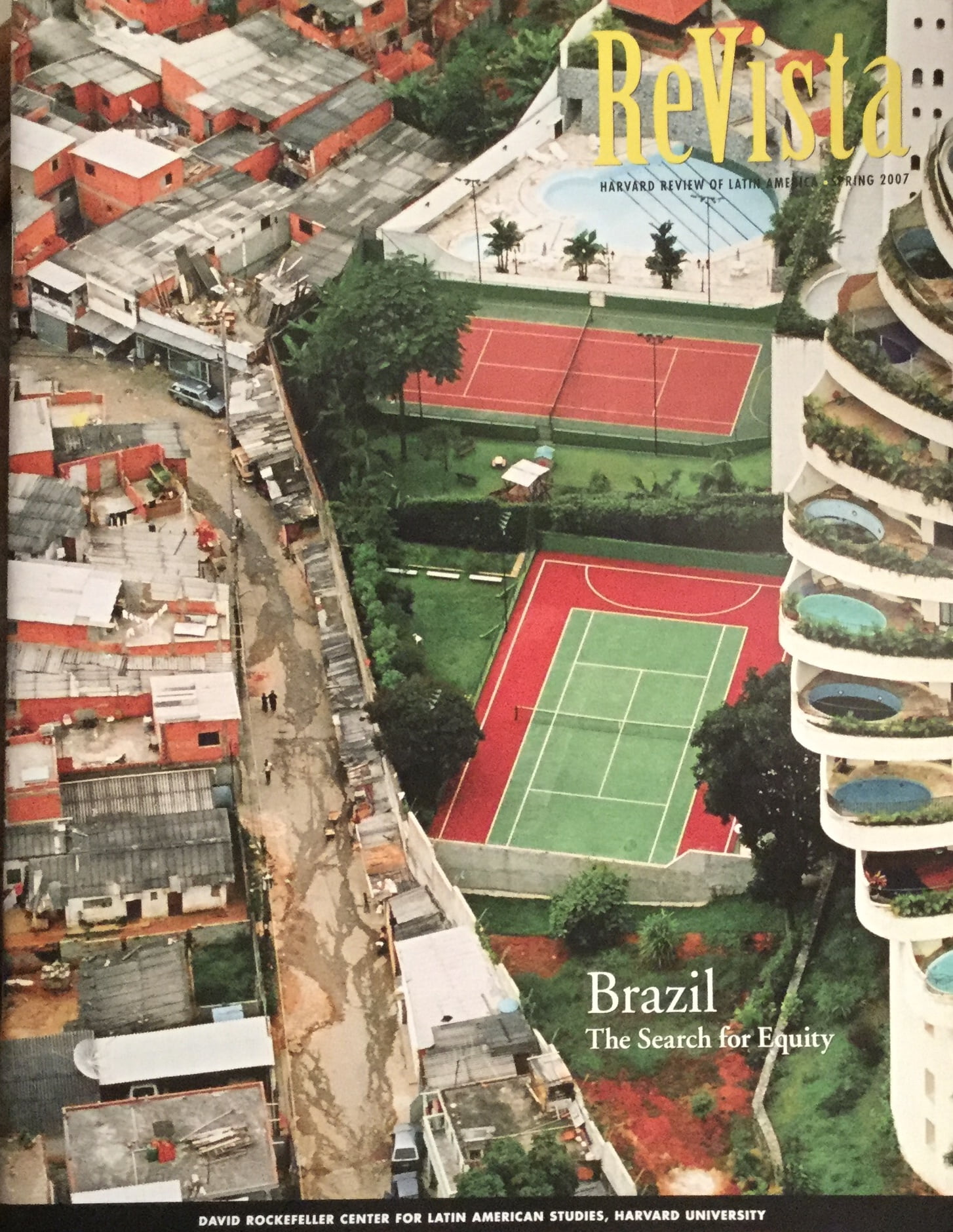

The social and racial divisions have not improved over the past 15 years since Tuca Vieira took his iconic photograph. It was in Paraisopolos, now the second largest favela in São Paulo, where 100,000 people live, that nine young people, attending the weekend “baile funk” on the first Sunday of December were shot dead (according to the military police), though they were more likely killed by suffocation caused in the panic as the military police intervened and blocked all exits, according to residents and the families of those killed.

Eduardo Bolsonaro (35) a congressman representing São Paulo, and the president’s third son (he received the largest vote in Brazilian history) took to Twitter to ironize the Paraisopolis victims. Eduardo Bolsonaro is the chair of the foreign affairs and defence committee in the lower house. His father wanted him to be the Brazilian ambassador to Washington. He is an acolyte of Olavo de Carvalho and more recently of Steve Bannon, and he has been the South American link in Bannon’s right-wing international populist organisation.

Last October in response to the widespread street protests in Chile and Bolivia, he suggested Brazil needed “a new AI-5” which was the Brazilian military regimes institutional Act 5 which gave it the power to override the constitution and inaugurated the most repressive period of military rule. His father has for many years praised the military regime. Eduardo Bolsonaro is a former federal police officer and lawyer.

The deaths in Paraisopolos at the hands of the São Paulo military police are far from being isolated cases. Up until October of 2019 the military police in São Paulo killed 697 people. In 2018 they killed 686. (The civil police in São Paulo over the same period killed 28 and 18 respectively). In Rio de Janeiro the police killings rose by 17% in 2019. Here the favelas and the high rises coexist in close proximity, often defined as the contrast between the “morro and the ashfelt” the contrast between the city street and the hill side self-made settlements that lack road paving and most city services. These hill side favelas narrow steps, irregular surfaces, overhanging buildings, channels of rubbish and sewerage, protected by and subject to extrajudicial punishments and protection rackets by drug gangs and the informal milícias of former police officers, are the most iconic favelas, but in reality in Rio de Janeiro the favelas also stretch much further inland to the north and far west of the city’s limits.

Here the disparity between locally available jobs and the resident population is enormous so residents must travel two hours a day each way to work in the inner city. The favelas of Rio have increased exponentially over the last half century, from 337,000 out of a total population in Rio de Janeiro of 3.3 million in 1960 (10.20%) to 1.313 million in a population of 6.2 million in 2010 (22.16%).

The same is true on the periphery of São Paulo as well as in occupied abandoned high-rise buildings close to the São Paulo city center. The consequences of these social and racial disparities show up in the Brazilian crime statistics which are the sixth highest index in the world in terms of homicides for 19 to 24-year olds: 7000 in Rio de Janeiro, 26 per 100,000 of the population. For young black men this means 400 per 100,000. The absence of the state and brute force is the norm for many.

Environmental Crisis

It is the crisis of the environment where Brazil is at the center of the global challenge and where what happens in Brazil has broad and inescapable international ramifications. Bolsonaro, like Trump, is a climate change denier. The US and China are the world’s largest contributors to carbon emissions.

But the threat to the Amazon rainforest has long attracted global concern and has created networks of powerful connected Brazilian and international activists, many of them high profile international figures, like the assassinated Chico Mendes in the past and the indigenous leader cacique Roani today, the British singer Sting in the 1980s, and American film star Leonardo DiCaprio more recently. Bolsonaro claimed that DiCaprio was bankrolling the deliberate incineration of the Amazon rainforest.

The “criminalization” of NGOs in Brazil by Bolsonaro’s government comes against the background of the global mobilization of young people against global warming who are demanding concrete responses to the pledges made at the Paris global climate change summit in Paris and the subsequent failed climate change meeting late in 2019 in Madrid where China, Saudi Arabia, Brazil and Australia, blocked meaningful resolutions. Bolsonaro not surprisingly attacked Greta Thunberg as “pirralha” (literally a little ”brat”or “pest”).

Donald Trump, another climate change denier, and also the master of insulting tweeted acronyms, agreed with Bolsonaro about the merits (or in their view the lack of merit) of Thunberg’s declarations.

The figures for 2019 for the burnings in Brazil are dramatic. The highest loss in rain forest in a decade, a 30% rise over the same period the year before. The attacks on Leonardo DiCaprio accused by Bolsonaro of bankrolling NGO’s to deliberately incinerate the Amazon rainforest and of Greenpeace for creating oil slicks along the Brazilian coast, are met with contempt outside Brazil. As was Bolsonaro spat in 2019 with Emanuel Macron, the French President.

Over the past year 3,700 square miles of Amazon rainforest has been razed. The cattle, soybean frontiers have been advancing all across the Amazon rain forest and along the Amazonian periphery in the Cerrado. Small prospectors, for gold, iron ore, and land grabbers and property speculators clearing forest land, are at the forefront of this violent, lawless, illegal cutting edge. Big agribusinesses are the beneficiaries. As is China which imports Brazilian agricultural products.

Bolsonaro in his first live press comments of 2020 promoting tourism in the Amazonian region returned to his attacks on Macron and Greta Thunberg who he again called a “pirralha.” Bolsonaro added: “Now that Australia is on fire l would like to hear if Macron has anything to say. He said he had asked his minister of defence and his foreign minister “to offer the little that we have to combat the fires in Australia.” He also praised Paul Guedes and his economic team.

The Culture Wars

It is not surprising that these conflicts find expression in acute culture wars in Brazil and they bring strange alliances and counter alliances. The military agrees with the notion that foreigners are envious and covetous of Brazil’s Amazon riches. The Vice President, General Mourão, certainly thinks so. Bolsonaro has long blamed the indigenous population for controlling large segments of the forest and preventing development there.

Bolsonaro’s guru, Olavo Carvalho, says that the “the greatest and most perfidious enemy of human intelligence is the academic community.” Bolsonaro agrees. ”Experts” are the enemy, and the Brazilian Universities (especially the federal universities which opened their doors to poorer students under the Lula government and introduced a system of quotas to encourage the participation of non-whites in the student body) are hot beds of “cultural Marxism” in Bolsonaro’s (and Olavo de Carvalho’s) world view.

Bolsonaro has placed his education minister. Abraham Weintraub, his minister for women, family and human rights, the Evangelical preacher, Damares Alves, and the disciple of Olavo de Carvalho, the Foreign Minister, Ernesto Araújo, at forefront of this cultural campaign. The nomination (since withdrawn) of Sergio Camargo to president of the Palmares foundation, a black Brazilian, who claimed that “slavery was terrible but was beneficial to the descendants of negroes brought to Brazil, where they lived better than the negroes in Africa” and who is a critic of “the day of black conscience.”

The Palmares Foundation was established in 1988 to promote Afro Brazilian art and culture and is named after the fugitive slave community which flourished in the interior Alagoas between 1605 and 1694 made up of communities of former slaves gathered in quilombos.

Bolsonaro appointed Letícia Dornelles a television telenovela producer to be president of the Casa Rui Barbosa in Rio de Janeiro. Located in Botafogo in the home where the eminent writer, politician and jurist and his family lived between 1895 and 1923, the Casa Rui Barbosa was the first museum established in Brazil in 1930 and houses his personal archive and library in a beautiful neo-classical building and garden and has been a beacon of cultural life for many decades and has been directed by many distinguished Brazilian scholars.

Letícia Dornelles first act was to dismiss the director of research and four researchers, all eminent scholars. She was indicated for the position by the neo-Pentecostal pastor of the “cathedral of avivament” and congressman from São Paulo, Marco Feliciano, an outspoken conservative and friend of Jair Bolsonaro. Feliciano was ordained in the US and is the head of 14 churches in Brazil. He plans to run for Vice President in 2022. He is notorious, like Bolsonaro, for his attacks on Africans, LGBTQ individuals, women and catholics. Africans he said are descended from “ancestors cursed by Noah.” He abhors the” promiscuous practices” of homosexuals. Giving women more rights would “undermine relationships and marriage as well as increasing the likelihood their children would be gay.”

Another front in this cultural war is Bolsonaro refusal to sign off the renowned Brazilian singer and novelist Chico Buarque de Hollanda’s award of the prestigious Camões Prize, which will nevertheless be awarded anyway in Lisbon in April 2020. In this Bolsonaro is facing many of his favorite enemies that he has spent 27 years in the Brazilian Congress railing against.

But the collateral victims of this cultural war are the young people killed in Paraisopolos, all them 14 to 23-year olds, all from the periphery, all of them devotees not of “bossa nova” but of baile funk. All of them “marginals” in terms of race and social class as far as the Military Police of São Paulo were concerned. The image of this “new” Bolsonaro Brazil is not that of the “Girl from Ipanema” on the beach in Rio de Janeiro, but of the 14-year-old Gustavo Cruz Xavier killed at a “baile funk” in the narrow alleyways of Paraisopolis in São Paulo.

The Greenwald Factor

The hyper involvement of the use and misuse of the internet and the international dimensions of these political conflicts is also at the heart of the activities of Glenn Greenwald in Brazil. Greenwald was responsible for the revelation of the hacked archive messages between the judge and prosecutors in the “car wash” investigation which had led to the unprecedented conviction of many leading businessmen and politicians, including former President Lula, conducted by former judge Sergio Moro. Jair Bolsonaro appointed Moro to be minister of justice in his administration and also promised him a freehand in reforming the criminal justice system and in combating corruption.

Greenwald is no ingenue. He is a New York born constitutional attorney whose law firm represented clients, many on a pro-bono basis, which included a white supremacy advocate and a neo-Nazi organization. In 2013 working with the British newspapers “The Guardian” he detailed the US and British global surveillance program based on information provided by Edward Snowdon. In 2014 funded by the founder of eBay, Pierre Omidyar, he established with two colleagues Intercept Brasil. There were claims that information on Hillary Clinton purveyed during his blogging days came originally from Russian intelligence sources. Greenwald has also been highly critical of US Democratic Politicians for what he considers their “anti-Russian” hysteria.

The most significant information revealed by Intercept Brasil was the release of private messages exchanged between the investigate judge Moro and the main prosecutor, Deltan Daliagnol, during the ”car wash” investigation, the ongoing criminal investigations by the Brazilian Federal Police, Curitiba branch, which began in 2014. These private messages were hacked apparently by Walter Delgatti Neto. The consequence of these revelations was to seriously undermine Sérgio Moro’s stellar international reputation and to severely embarrass many (both within Brazil and internationally) who had praised his anti-corruption campaign, as well as to jeopardize many of the successful corruption convictions. Which were indeed spectacularly successful.

Using plea bargains the “car wash“ investigations interrogated 429 individuals, in 18 companies, in corruption case involving more than 11 countries, and convinced 159 major political and business figures. All of which was unprecedented. But Greenwald’s “Intercept” revelations do not seem to have seriously damaged Moro’s reputation in Brazil. Moro was in a DataFolha opinion survey in the January 2020 the Brazilian in which the population has “most confidence” (33%) followed by Lula (30%) Bolsonaro (22%) and Huck (21%). Though it should be noted that all also have low confidence rates (Moro 42%) (Lula 53%) (Bolsonaro 55%) (Huck 55%). But a real consequence has been a weakening of the anti-corruption momentum in Brazil.

Greenwald is also at the heart of the cultural wars Bolsonaro is waging. While in holiday in Rio Janeiro he met on the beach at Ipanema a handsome young Brazilian. It was a case of “the boy from Ipanema“ twenty-first century style. Greenwald fell in love. David Miranda and Greenwald are married and have two adopted children. Miranda is now a Congressman from Rio de Janeiro. Miranda and Greenwald both have a very high profiles In Brazil, and Greenwald as a major interpreter of Brazilian events to the outside world.

David Miranda and Glenn Greenwald have both received death threats in Brazil, which should not be underestimated. A good friend of theirs, the Rio de Janeiro council women, Marielle Franco, who had taken on the militias, was assassinated, and Miranda himself took up the seat in Congress of an openly gay Rio congressman who is now living in exile after death threats. Greenwald and Miranda both epitomize everything about the alternative Brazil that the homophobic Bolsonaro and his family and their sour “guru” in Virginia most hate. It is for them all a very personal and individual cultural war.

Shift in Brazil’s International Policies

The arrival Jair Bolsonaro in office also marked a major shift in Brazilian international policy. In 2020 Brazil has become very much part of the Trump (and American) camp. The days of Lula’s skepticism about the United States, and his opening to Africa, Venezuela, Cuba, and the Islamic world is long gone. But navigating these international shoals will not be uncomplicated for Bolsonaro in 2020.

Trump is an unpredictable friend and Trump is above all a transactional and not an ideological president and he faces an election campaign in 2020. In Brazil’s neighborhood in Latin America tensions will continue in 2020. Social unrest and street protests have already sent shock waves across the region from Chile to Colombia.

Venezuela is in permanent and unresolved crisis and millions of Venezuelans have fled the country including into Brazil. Brazil will strive to avoid contagion. Jair Bolsonaro will face the need to conciliate the ideological driven and pragmatists within his own government.

He will need to bring economic growth.

None of these easy tasks within an angry and divided society he has done so much to instigate and on which his political fortunes depend.

Coda: Goebbels Pops Into the Brazilian Discussion on Culture

An article published by Journalists Livres highlighted the appearance of the infamous Goebbels into the Brazilian context:

The Special Secretariat of Culture of Brazil has just released a video in which the Secretary of Culture Roberto Alvim announced a funding program for the arts. In a well centred frame and with a piece from Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin on the background – the same used in Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator -, a well groomed and brilliantine haired Roberto Alvim, with a picture of president Bolsonaro above him, a Cross of Lorraine on his left and the brazilian flag on his right, describes the Bolsonaro’s government guidelines for the arts: patriotic, linked to family values, connected to god and virtues of faith.

A few minutes into his speech, he delivers a pearl: an almost identical quote from the infamous Nazi Germany Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels:

“The Brazilian art of the next decade will be heroic and it will be national, it’ll be endowed with great capacity for emotional involvement and deeply committed to the urgent aspirations of our people, or it will be nothing.”

The Goebbels quote, probably taken from his biography by Peter Longerich, which was published in Brazil in 2014, reads as follows:

“The German art of the next decade will be heroic, it will be steely-romantic, it will be factual and completely free of sentimentality, it will be national with great Pathos and committed, or it will be nothing.”

The resemblance is too clear to be an accident, or even a mere inspiration. It’s an explicit reference. What Mr. Roberto Alvim means by it, if it’s a tip on the path Brazilian government wants our culture to follow, or just a provocation meant to unsettle the left, it’s unclear. It is, though, undoubtedly, very unsettling.

Watch the full video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YiO23U59CdU

And the follow on to this story: Bolsonaro fires hist cultural minister.

President Jair Bolsonaro’s top culture official was dismissed on Friday over an address in which he used phrases and ideas from an infamous Nazi propaganda speech while playing an opera that Adolf Hitler regarded as a favorite.

The address by Roberto Alvim, the culture secretary, set off an outcry across the political spectrum as Brazilians reacted with exasperation and incredulity.

It was the latest flash point in a broader debate over freedom of speech and culture in the Bolsonaro era. The president campaigned on a promised course correction after an era of rule by leftist leaders, whom he accused of trying to impose “cultural Marxism.”