By Robbin Laird

The Australian Offshore Patrol Vessel or the Arafura Class OPV program is the launch program for the new Australian approach to shipbuilding.

Termed a “continuous shipbuilding process,” the core point is to have an ongoing shipbuilding effort, rather than a start and stop approach built around a single platform naval acquisition, one at a time.

But the new approach is more than that.

It is about shaping a new industrial-government partnership and having a new role for the lead contractor working with Australian suppliers.

This article is the second of three.

I have had the chance to visit the Henderson shipyards, and an opportunity to talk with Luerssen and Civmec, the two partners in the Australian Maritime Shipbuilding and Export Group (AMSEG).

In the first article, I addressed the role of Luerssen; in this I am addressing the role of Civmec.

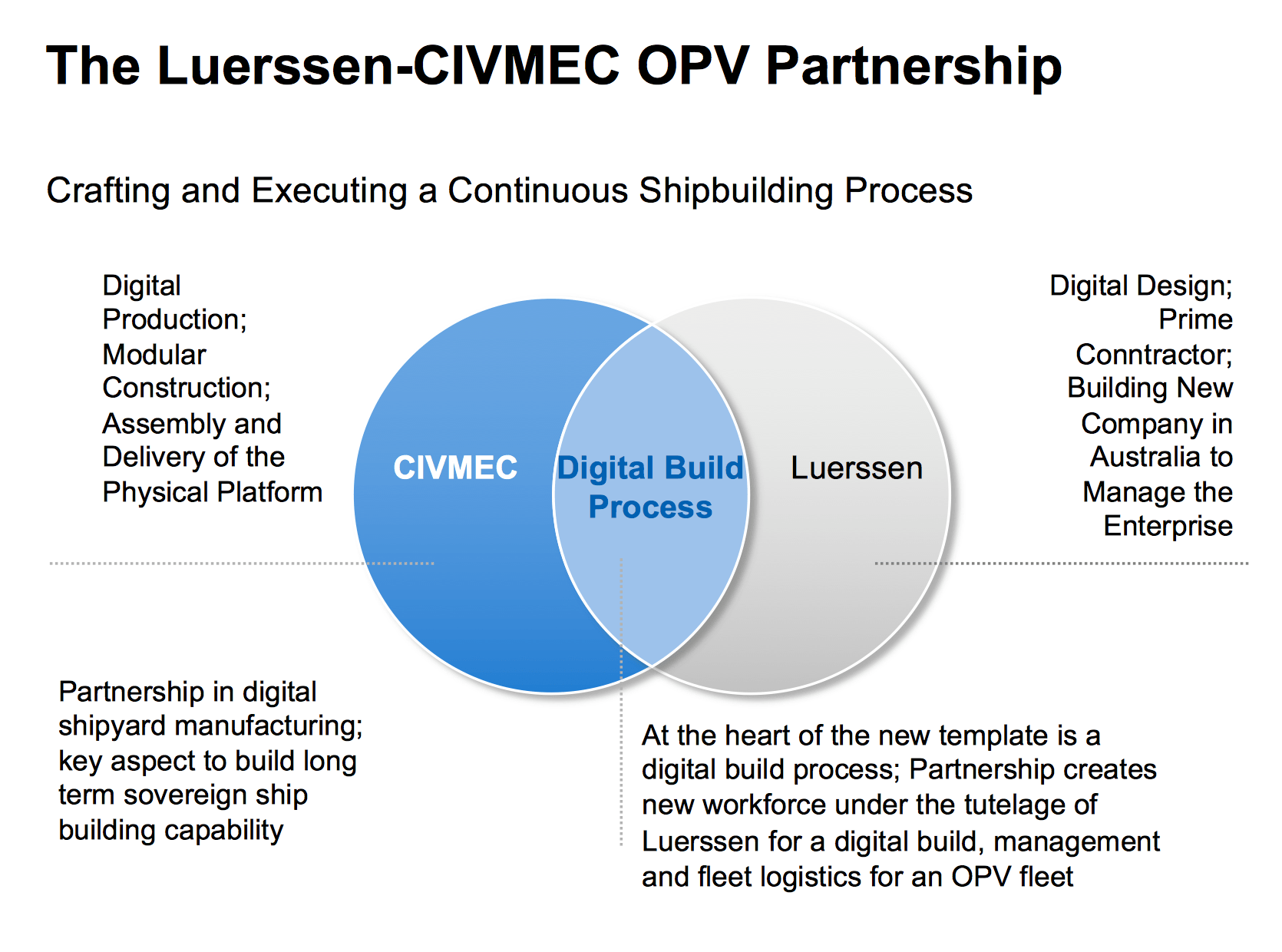

My graphic below highlights how the partnership is working:

When I first learned that Civmec was going to be the major build partner of Luerssen, I must admit that I was a bit surprise: Civmec is a shipbuilder?

Clearly, they are a major Australian company in building infrastructure, and in steel production, but certainly, they are not a household name in shipbuilding.

But since my original reactions, I along with the Australian public have begun to learn more about the company and what they do and how they work.

With my visit to Henderson, I was able to talk with two senior Civmec officials as well as to review the public information provided by the company to sort through who they are, what they are doing, and why selecting them as the build partner for Luerssen made a great deal of sense.

During my visit, I met with Jim Fitzgerald, Executive Chairman of Civmec, and with Mark Clay, Project Manager, formerly of Austal and now with Civmec.

I am not going to quote them directly in this article, but will highlight my key takeaways from my search of the public available data, discussions held in Perth, Adelaide, Canberra and Sydney with Royal Australian Navy and Commonwealth officials, and my meetings at Henderson.

The first key takeaway was my having missed core competence of the company in plain view.

It is clear that in my initial read of the Civmec choice, I had missed one major area in which they work which is central to shipbuilding; they are players in the oil and gas offshore platform business. These are certainly sea bases and of relevance more generally to managing a shipbuilding enterprise.

A second key takeaway is the significant investment which Civmec made in shipbuilding PRIOR to the award of the OPV contract.

Notably, in 2016 Civmec announced that the Company had executed an Asset Sales Agreement for the acquisition of Australia’s largest privately-owned engineering and shipbuilding company, Forgacs.

Following the due diligence process and subsequent negotiations the company decided that the acquisition will include the Forgacs name, the shipyard facilities, and the assets located at Tomago, New South Wales…

This provided Civmec with a significant East Coast presence in the ship building and maintenance business as well as enhancing its overall portfolio in the maritime industry.

This is how Civmec in the brochure on the company describes this addition to the company:

In February 2016, Civmec acquired Australia’s largest privately-owned engineering and shipbuilding company, Forgacs, including its shipyard facilities and assets located at Tomago, New South Wales.

This strategic acquisition, through an asset sale agreement, has enabled Civmec to develop its East coast operations through the landholding and associated assets. The purchase included IP developed over decades of operation across the Defence sector.

Commencing operations in the 1960s, Forgacs forged a strong name in the shipbuilding industry, delivering major programs for the Royal Australian Navy, including the conversion of HMAS Manoora and HMAS Kanimbla into amphibious helicopter support ships, as well as hull modules for the ANZAC frigates and the Air Warfare Destroyers program. The Tomago shipyard has built some of Australia’s iconic ships including the ice breaker Aurora Australis, HMAS Tobruk and hull sections of Collins Class submarines.

The company’s shipbuilding capability has been further enhanced since the acquisition with the engagement of industry specialists, positioning us for future shipbuilding and sustainment opportunities.

The third takeaway was provided by Jim Fitzgerald at the beginning of our session where he went through the transformation of the Henderson yard from 2010 to 2020.

His portfolio of photos highlighted the transformation of the yard through this 11-year period from a fairly limited facility to a much more robust infrastructure to support shipbuilding and maintenance.

He noted throughout that Civmec was investing in its future in the maritime business prior to and obviously after having received a contract to work on the new Australian OPV.

Just taking a look at three points in history at the yard certainly highlights the effort, and the commitment of Civmec to build a 21st century shipbuilding and maintenance facility.

This is a shot from 2009:

And this is a shot from 2016:

And this is a shot from 2019:

And what you see in the picture above, is a facility which I visited during the site tour and it is not only completed but went from flat ground to completion in only 18 months.

The fourth takeaway was that the build of the first two Arafura Class OPVs at the BAE/ASC yard in Adelaide was not taking away from the effort of Civmec for the overall program or its preparation to build the remaining ships in the program at Henderson.

The materials being cut to build the ship are being done at one facility, not two, and that facility was the one which I visited in Henderson. The material is shipped from Henderson to Adelaide by road and rail and given that the cost of transport West to East is significantly less than East to West, the cost factor of having the initial assembly in Adelaide rather than Henderson is very manageable.

This also allows the Henderson yard to have a two-ship run through prior to launching full production at Henderson.

This is a digital production facility which is clearly evident when you visit the cutting facilities at the yard, where precision is the name of the game and where the production workers and staff are managing a digital production process.

This includes having a control room which is monitoring the parts flows into the yard and working schedules that are designed that materials for production arrive just in time for the production process.

The fifth takeaway was that the yard had been built with a clear build process which could take the manufactured parts, work those into modules for the final assembly process, move those modules then into the paint and then assembly hall areas and then when the ship is completed over to the floating dock for final completion and acceptance.

And this is done on the real estate of the single yard.

The graphic below gives one the sense geographically of this workflow:

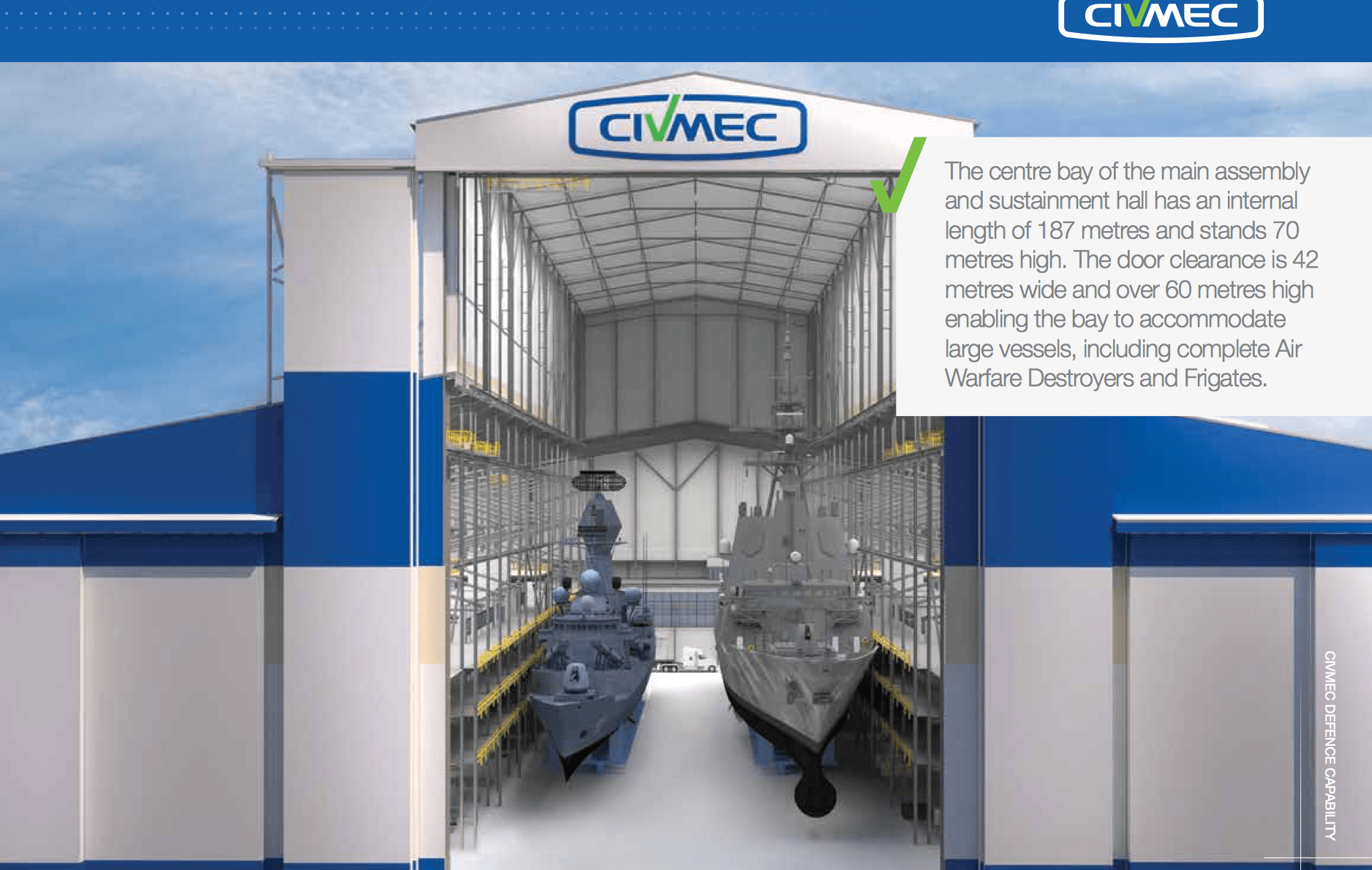

The sixth takeaway is that the main assembly and sustainment hall is massive and can accommodate the Royal Australian Navy’s ship up to the size of the Air Warfare destroyer.

The graphic below highlights the assembly hall:

This approach clearly meets the concept of how the Commonwealth wants to approach to future of sustainment of its fleet.

When at the Seapower Conference held in Sydney last Fall, I listened to a presentation by Rear Admiral Wendy Malcolm, Head of Maritime Systems Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.

Rear Admiral Malcom highlighted the importance of ensuring that a new sustainment strategy be built into the build out of the next generation Australian navy.

She argued that the Australian government has committed itself to a step change in naval capability. Australia will be engaged in the most significant recapitalization of its Navy since the Second World War.

“We need to reshape the way we sustain our fleet as we go about a significant change in how we are doing Naval acquisition.”

“As a result, we need to future proof our Navy so that it is capable and lethal and available when and where they are needed.

“We need to build a sustainment model which ensures that we can do this as well.”

Sustainment has been largely thought of as the afterthought to acquisition of a new platform.

She argued that with the new “continuous shipbuilding approach” being worked, sustainment needs to be built in from the start into this process approach.

“We should from the outset to consider the best ways to sustain the force and to do so with engagement with industry in the solutions from the outset.”

She noted that the acquisition budget is roughly equivalent to the sustainment budget, and this means that a new approach to sustainment needs to accompany the new acquisition approach from the outset to ensure the delivery and operations of the most lethal and capable combat fleet which Australia can provide.

“There are serious external and internal forces that are forcing change in our thinking about how we will use our fleet…. A major investment in shipyards, work force, and in new ships requires an appropriate sustainment approach to deliver the capability to do the tasks our navy is and will be required to do.”

The shift to “continuous ship building” entails a major shift in how Australia needs to think about sustainment as well. She argued that a number of technologies had emerged which allow from a more flexible and adaptative way not only to build but to sustain ships as well.

“We need to take a fleet view and to shape a continuous approach to sustainment as well.”

Rear Admiral Malcolm dubbed the new approach of a continuous sustainment approach or environment as Plan Galileo.

Clearly, Civmec is ready for Plan Galileo.

The seventh takeaway is that clearly Civmec was well positioned for digital shipbuilding and sustainment for as early as 2012 they had introduced an information management system which is a clear foundation to support a digital approach.

This system is called “CIVTRAC,” and is described in the Civmec brochure as follows:

We are certified to ISO 9001, the internationally recognised standard for quality management, and our heavy engineering facilities have also achieved CC3 certification to the requirements of AS/NZS 5131-2016. We have also obtained certification to ISO 3834.2:2008 – Quality requirements for fusion welding of metallic materials (Part 2: Comprehensive quality requirements).

Utilising Civtrac, our proprietary web-based integrated business management system, we are able to accurately provide ‘live’ tracking, managing all aspects of project delivery, including:

- Document Control

- Material Control

- Project Management and Reporting

- Safety Management

- Quality Control

- Cost Management

With 3D model interface, the productivity tracking, quality control and completion management activities undertaken in the field, recorded on tablets in real-time, facilitate Civtrac’s seamless flow from fabrication through to installation and commissioning.

Civtrac also enables our clients to directly monitor real-time progress via a remote login, providing transparency across the entire project life-cycle, from material control to delivery and installation.

In short, Civmec has put in place a capability to engage in and support the “continuous shipbuilding approach.”