By Robbin Laird

The Australian Army faces a significant challenge as it adapts to its role within the ADF and as the ADF refocuses on the Indo-Pacific.

A clear consideration is how the Army will address force mobility, basing flexibility, and operate within an integrated air-maritime task force.

Several years ago when visiting MARFORPAC, a key dimension of the rethink going on then was about the expanded role for amphibiosity in the context of blue water expeditionary operations and force mobility.

In that 2015 interview with Brigadier General Mahoney, Deputy MARFORPAC, we discussed the evolution of defense in depth and amphibiosity.

Last year I visited MARFORPAC, and interviewed the staff and the then head of MARFORPAC, Lt. General Robling During my last visit, I focused on the broad strategic restructuring which the Marines were undergoing which they refer to as the distributed lay-down.

The U.S. Marine Corps is in the throes of a significant shift in the Pacific in the disposition of its forces. Because two thirds of Marines are deployed to the Pacific, such a shift is a key event in shaping the Marine Corps stance in the decade ahead.

The demand to support distributed forces is rising and will require attention to be paid to the connectors, lifters and various support elements. Part of that demand can be met as allies modernize their own support elements, such as Australia and Singapore adding new Airbus tankers, which could be leveraged to support Marine Corps Ospreys as well as other aircraft.

Indeed, a key element of the distributed lay-down of our forces in the Pacific is the fact that it is occurring as core allies in the region are reshaping and modernizing their forces as well as partners coming to the table who wish to work with and host USMC forces operating on a rotational basis with their forces. The military and political demands for the kind of forces that the Marines are developing also are what allies and partners want for their operations.

In turn, this drives up the importance of exercises in the Pacific with joint and coalition forces to shape new capabilities for the distributed force.

The distributed lay-down, the evolution of the capabilities for distributed forces, the modernization of allied forces and the growing interest in a diversity of partners to work with the USMC are all part of shaping what might be called a deterrence-in-depth strategy to deal with the threats and challenges facing the United States and its allies in shaping a 21st-century approach to Pacific defense.

In a visit to Hawaii on the way to Australia in late July 2015, I had a chance to sit down with Brigadier General Mahoney, Deputy Commanding General of U.S. Marine Corps Forces Pacific.

The key focus of discussion was on the evolving approach to shaping a coalition among amphibious nations in the Pacific, and the concurrent evolution of capabilities by the USN-USMC team with regard to their own amphibious capabilities under the twin impact of the Osprey and the coming of the F-35B to the fleet in the Pacific.

In May 2015, the Navy and the Marines hosted a first ever meeting of nations either with or aspiring to shape amphibious capabilities in the region.

“We just had the PACOM Amphibious Leaders Seminar here, PALS 2015, the first of its kind. Twenty-four countries either have an established capability, a burgeoning capability or an interest in amphibious operation. The PALS, the symposium I think was a great success just in folks who wouldn’t have ever talked to each other were now talking directly. We connected a matrix of people who now understand that there are other friends and capabilities out there that they can connect with. And I think we’re going to try and do that again next year.”

The clear focus of an emerging coalition is upon the application of amphibious capabilities to the 21st challenges posed in the Pacific region. How best to shape and use the tool sets provided by amphibious forces?

The May conference is an important step forward in shaping a narrative to craft a teaming approach for amphibious operations.

“One of the larger points in the evolving narrative is the teaming of force projection capabilities where the amphibious element is a core capability. It is not simply about amphibious ships being transport vessels; it is about reshaping forces to deal with 21st century operations.”

BG Mahoney discussed how under the concept of amphibious, there are very different notions at play, ranging from a transport and support fleet to a strike or force insertion fleet.

The term “amphbiosity” was used to express the broad umbrellas under which diverse notions of what kinds of amphibious forces a nation might wish to operate.

“What we learned during the, the PACOM Amphibious Leaders’ Symposium was what people understand and appreciate with regard to amphibiosity is sometimes completely different. There are close partners as well as some in our own joint force who in their mind’s eye really view amphibiosity as a floating a chow hall, an airfield, a hotel, and a mode of transportation; not a maneuver element, not a C4I node, not a presence effect.”

But clearly, the shortfall in amphibious ships, and support vessels, is of concern the Navy and the Marines.

“The demand side for Phase Zero operations in the Pacific is insatiable. And now we are in the process of distributing our presence among several different locations in the Pacific. Great, but how do we connect all of this into a true operational network? A challenge is that we do not have enough L-class ships; the Commandant and the CNO have made this point very clearly.”

When asked if investment could be increased where would he put it to deal with the demand rhythm and distributed operational requirements, the BG put it this way:

“Give me my 10th Amphibious Ready Group, and more L-class ships in the FDNF (Forward Deployed Naval Force). Then in teaming with PACFLEET, get after the job of dealing with the demands in the Indo-Asia-Pacific which is a growth industry.”

Given the high demand tempo, the Navy and Marines cannot wait around for the proper number of ships to show up, so the approach is to work a broader amphibious coalition and to work various pairings between grey hulls and MSC ships.

“I think that there’s a huge area under the curve to be exploited in experimentation and pairing, or combinations of, gray hull ships with other class ships. I know that in some quarters, that notion is blasphemy; it’s the proverbial slippery slope. But the fact of the matter, it is a practical reality that we need to explore capabilities in combining hulls like LMSR, TAK-E, AFSB, MLP, LCS, JHSV with that L-class ship and see what we can do with it, not assume what we can’t do with it.”

It should be noted that pairings do not make an MSC ship as capable as an L-class ship; but they do provide for greater operational sustainability and enablement of the L-class ship. In a discussion with the Navy, a senior Naval captain made a key point that pairing is crucial as long as one does not equate each member of the pair in terms of capability. A gray hull is neither an MSC ship nor does an MSC ship magically have the capabilities of an L-class ship….

In short, the Marines are leading the way in transforming the very meaning of amphibious operations.

We are only at the beginning of understanding what an F-35B and Osprey enabled amphibious fleet can do and might do; and with it the leavening effect such capability can have on the evolution of a Pacific amphibious coalition.

But one thing is certain: the MARFORPAC organization is crucially involved in shaping an evolving future.

That was five years ago; now as the Australian Army faces its evolving future, how will it tap into the dynamics of USN-USMC integration for blue water expeditionary operations?

The argument can be put simply.

First, the new Australian defence strategy focuses on defense in depth and mobile defense out to the first island chain for Australia which is the Solomon Islands.

Second, the roles of integration of the RAAF and the RAN are quite clear in this strategy, but the Army less so.

Third, the de facto role of the Australian Army is to provide for defense of Australian territory by enhanced mobility within the continent, including base and missile defense.

In the new strategy, the roles of Western Australia and the Northern Territories is enhanced.

The role of the Army in providing for base protection should go up as well.

But the Australian Army in its land wars Middle Eastern phase has become U.S. Army like; not USMC like.

The new strategy de facto calls for a more Marine Corps like Army.

But can the leadership embrace such a shift, even while embracing the concept of an “Army in Motion.”

The outlier in this discussion is the question of how the Australian Army approaches mobility, mobile basing and even expeditionary basing.

And what role the afloat assets would play in this effort; and as well, how the Royal Australian Navy looks at the amphibious force as it looks to expand its integration across the fleet to contribute to the mobility options out to the first island chain?

In a recent discussion with an Australian Army colleague he highlighted the challenge this way:

“Our ships were largely acquired just to fulfill a mobility need rather than combat need.

“It has not been central to our thinking for sure.

“We’re in an area of operations predominantly enabled by others, and the United States, in many cases.

“But we understand the idea of what used to be sea basing, but we haven’t really conceptually organized things.

“For Army, this is a new capability that’s designed to get to the area of operations and then supporting those operations.

“We have fit our thinking into an approach to mobile basing, but conceptually, we haven’t really grasped the whole picture of sea-basing and operations as the USMC is addressing these operations.”

A recent discussion with Brendan Sargeant, the well respected and well-known Australian strategist, underscored how significant the strategic shift facing Australia is and notably, underscored how the strategic shift impacted most directly on the question of the future of the Australian Army in the decade ahead.

According to Sargeant, “As we focus on our region, Army will have a key role, but in terms of the joint force.

“How best to work their role?

“What do they need to be able to do in the joint and integrated force context?

“One answer clearly would be for the Army to focus on how their new interest and capabilities in amphibious warfare would work within a regional joint force context?”

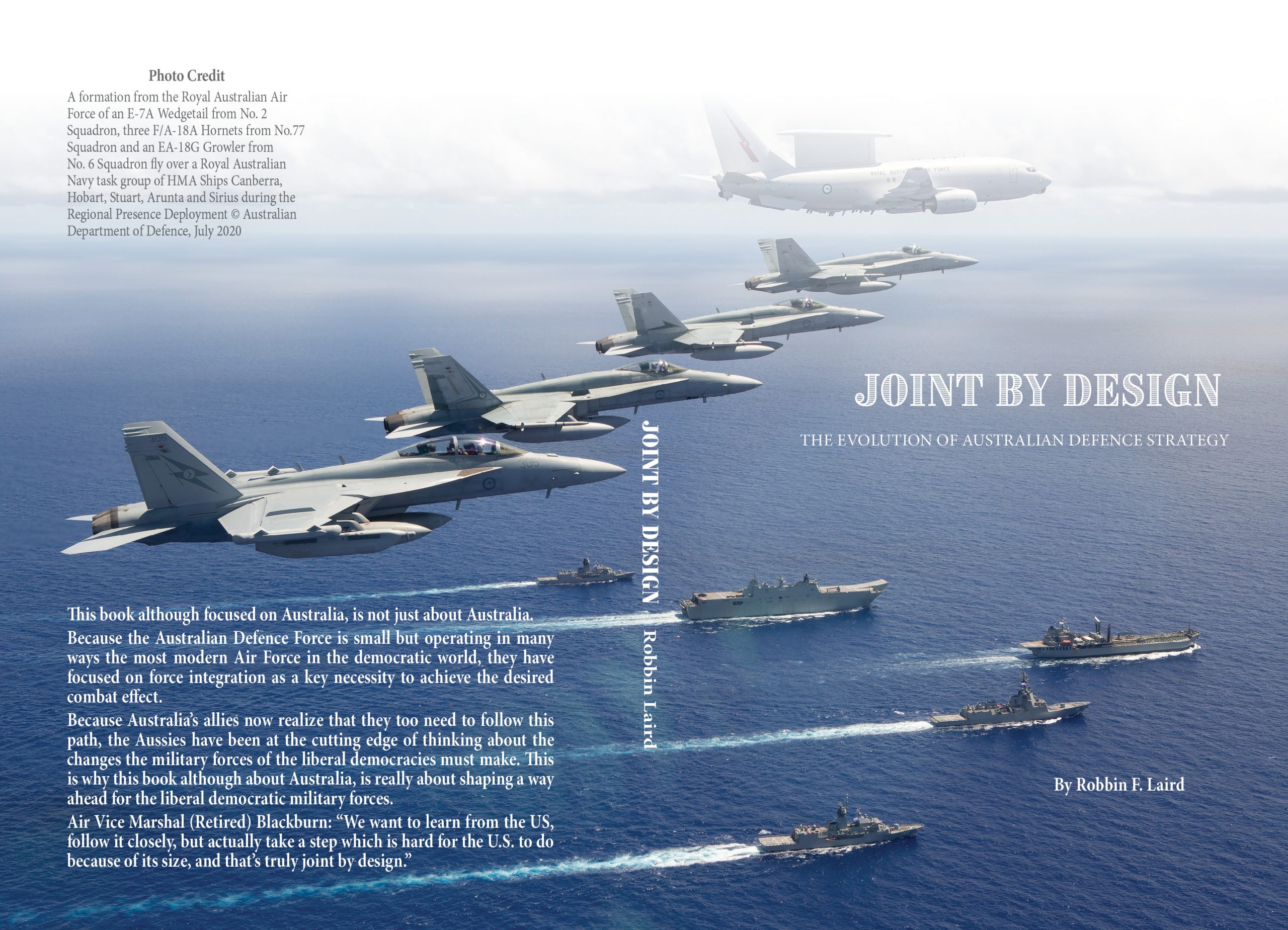

Featured Photo: HMAS Canberra departs the Port of Darwin to commence the Regional Presence Deployment 2020 in Southeast Asia and off the coast of Hawaii.

Later this year, we are publishing a book on the evolution of Australian defence strategy.

In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, the prime minister of Australia, Scott Morrison, launched a new defense and security strategy for Australia. This strategy reset puts Australia on the path of enhanced defense capabilities.

The change represents a serious shift in its policies towards China, and in reworking alliance relationships going forward. “Joint by Design” is focused on Australian defence modernization and policy, but it is also about preparing liberal democracies around the world for the challenges of the future.

Also, see the following:

The Australian Army in the Decade: Resilience, Regionalism and Relevance