By Murielle Delaporte

Sahel is among the worst nightmares for any counter-terrorist expert and planner.

It feels like the old saying of getting rid of an enemy through the door before it comes back – regenerated or under a different form – via the window.

In some ways the level of danger and violence resembles the early 2000’s with the same type of alliances between the Touaregs of Northern Mali and Al Qaida terror groups which triggered the Malian government to request Paris help to roll back the Islamist threat,

The Serval operation in 2013 became Barkhane in 2014 in order to enhance regional stability among the newly created G5 Sahel group which includes in addition to Mali, its neighbors Niger and Burkina Fasso, as well as Mauritania and Chad on each side.

Since 2013 a myriad of organizations and countries have been acting like fairy godmothers providing financial help for development and military support to fight violence, and the number is still growing as more European partners’ special forces are in the process of joining the recently created Takuba Task Force.

The U.S.-supported but French-lead Barkhane operation has been successful in containing the Jihadist threat, but has not been able to fully eradicate it, as the negative spiral between terrorist attacks and the resulting increased poverty and migrations keep feeding each other.

The real origin of this centuries-old regional chaos has indeed mostly to do with the immensity and the harshness of the territory, making it difficult for any state authority to settle and provide governance, food, jobs, as well as education.

Terror groups come and go constantly adapting to the security posture and regenerating while living on the multiple traffics the geography allows (humans, drugs, arms, etc).

Figures of increased attacks and civilians’ deaths would be enough to discourage any attempt to go on and try to get rid of a few thousands agile and deadly fighters bringing hell on a daily basis to terrorized populations.

However, they mask another reality on the ground, which is the breakthrough of having the G5 countries recognizing they have to unite to fight their common enemies. If bilateral or trilateral mixed patrols between Sahelian countries and Barkhane, as well as with Niger-based U.S. forces, have been existing since the Serval aftermath, the concept of an all-African regional military coordination allowing the conduct of operations is rather new. And such a force is tailored to deal precisely with jihadist groups grafting themselves on the misery of populations caught in the middle of multiple and multiform strife.

The G5 Joint Force In Sahel : A Promising Case Study of a Way Ahead

The G5 force was authorized by the African Union Peace and Security Council in April 2017 and was strengthened by the adoption of UN Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2359 in June.

It was shaped on the basis of lessons learned from the Multinational Joint Task Force (a combined multinational formation comprising units from Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria to fight Boko Haram) as well as other similar experiences (Somalia). The G5 Joint Force in Sahel (or FC-G5S for ‘’Force conjointe du G5 Sahel’’) was meant in its current Commander (COMANFOR), general Oumarou Namata Gazama’s words, ‘’to respond to the regional nature of the threat and to fill the trans-border security gap in order to accompany the G5 Sahel in carrying on with its credo : Security and Development.’’

The approach has focused in countering the spillover of terror groups between Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso in the area known as ‘’the three borders.” Before 2017, none of the armed forces of these countries were allowed to pursue their enemies in the neighbor’s territory. The terrorist groups took advantage of such a weakness to spread and hide before regrouping.

But now the G5 Joint Force can operate in three 200-kms sectors (it used to be only 100 kms and the area of operation keeps increasing, which is a sign of the existing virtual circle between success and confidence). After a false start caused by a deadly attack on their headquarters in Central Mali in 2018, the

G5 Joint Force in Sahel has been generating and training its forces (currently comprised of 7 battalions and a total of 4,000 men). These successes have been evident last year. The joint command has gathered not only the three African countries, but also French and U.S. military officers in Niamey, Niger, wide-ranging operations. And these operations were able to be planned and coordinated with others led by national armed forces, the Barkhane Force as well as with the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali initiated since 2013 (MINUSMA).

As an example of the typical multilateral cooperation that goes on the ground on a regular basis, a recent major operation designed to control a 300-mile wide specific area of the theater involved 3,000 troops, half of which originating from Mali and Niger. This operation was also not only supported by U.S., British and Danish air and ISR assets, but also (and for the very first time) by French and Estonian special forces from the Takuba Task Force. And these forces operated along with units from Mali and Niger as well.

Backing the efforts of the G5 Joint Force in Sahel provides an example of how Western and African forces can work together to not only contain but contribute to eradicate terrorist violence and control illegal trafficking in the region. And this is being done without a large contingent of western boots on the ground which would simply generate another endless war.

At the same time, the G5 Joint Force provides a way to continue Western engagement to work with Africans to deal with the ongoing terrorist challenges in Africa, Europe and beyond. Supporting a toolset such as the G5 Joint Force in Sahel constitutes in that sense a genuine springboard for future transnational stability, accountability and peace, as its main focus is cross-border operations coordination, which is key to fight the terrorist groups’ and counter their strategy.

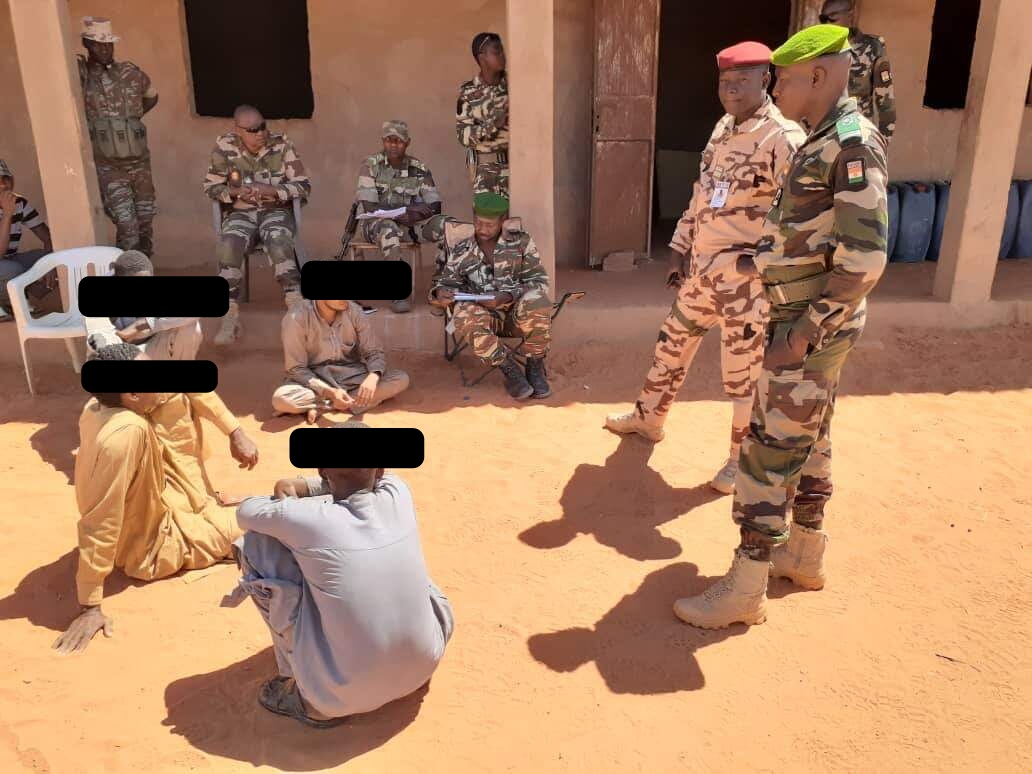

Source for the photos: G5 Sahel facebook September 2019

An earlier version of this article appeared on Breaking Defense.