By Robbin Laird

The ADF faces a double challenge.

First, there is the transition from the away game land wars to preparing forces for higher intensity operations against global authoritarian powers. I have written several books which address how challenging this shift is for a whole generation of warriors and policy makers who have only known the land wars as a core focus for their defense forces and efforts.

But Australia faces a second challenge affecting the future of the ADF as well: where is the ADF going to operate primarily in the direct defense of Australia?

What exactly is the defense perimeter for Australia?

How best to operate within that defense perimeter?

And how to sustain the force for the time needed to prevail in conflict or crisis management?

In a recent meeting held with Colonel David Beaumont, an Australian Army officer, and both a practitioner and analyst of logistics for the joint force, he underscored the importance of the ability to persist in conflict situations.

This is how he put it: “The belligerent who can respond quickest and can return to support the combat force will be the one that emerges and the greatest chance for success.”

Added to the strategic calculus for the ADF has been living through the pandemic. What the pandemic has underscored is how vulnerable global supply chains are and the need for Australia to build more reliable supply chains in the face of dealing with global disruptions (and in war these will be deliberate efforts) as well as more national production capability and stockpiling for greater resilience where appropriate.

This may also include working with coalition or alliance partners, in a broader conception of what is known in Australia as a ‘national support base.’

Or put another way, the next phase of ADF development will be built around the direct defense of Australia and its ability to operate within its core defense perimeter with an integrated but distributed force, and able to mobilize a sustainment system for operations, but that will only occur with the broader capability of the Australian nation to mobilize as well. Mobilization is not simply an ADF concept; but it is a whole of nation one.

This is how Beaumont put it in our conversation: “We need to go beyond simply discussing ADF mobilization in a crisis. We need to understand what the limits and constraints are on what the ADF can do for itself and what might it need from the nation. This will help us understand exactly what capabilities or support mechanisms need to be built within the ADF, or what policies and plans may be required to help govern national responses to a crisis.”

In a recent article by Beaumont and published by ASPI on September 8, 2022, Beaumont provided his understanding of how to understand the challenges associated with enhanced ADF mobilization with that of the broader society or nation.

“Access to supply chains and civilian resources also influences where forces are based and prepared. It’s timely to remember lessons from the 1999 peacekeeping mission to Timor-Leste, Operation Warden, when the unplanned deployment of 10,000 coalition forces put a tremendous strain on the Darwin infrastructure. If the defence strategic review orients force posture to Australia’s north, an in-depth conversation about what infrastructure is required for military forces must follow. When civilian infrastructure is unavailable, the ADF must be structured to support itself. Expeditionary logistics capability may be in order.

“Civilian and military logistics and infrastructure, working together, ensure that military power is in the best position to be used. It is, however, virtually certain that infrastructure capability won’t be met by a comprehensive list of defence projects that’s been ‘optimised’ to treat all logistics and infrastructure needs. The defence budget is far too small to create the national economic infrastructure necessary for the types of scenarios that Australia should be prepared for, especially as step-change military capabilities are being introduced to offset the efforts of other nations.

“A range of civil–military measures to coordinate the development of infrastructure, if not other logistics and supply-chain issues, will be required. The needs will always outweigh the resources available to treat them, and the art of logistics and infrastructure development will come in the way that those involved in decision-making qualify, quantify and manage risks. What is needed, at the very least, is a conversation about the strategic concepts that underpin the making of decisions as envisaged in the defence strategic review.

“The community of discourse on this issue already knows that the only viable solution is a collective one. There are three broad perspectives relevant to this outcome. First, the military perspective looks to the potential circumstances of operations and produces concepts that reflect strategic guidance and enable logistics requirements to be determined. The question for the military planner is not necessarily whether the requirements can be met now, but whether the infrastructure can be made ready when it is needed.

“The second perspective is civilian (government and industry) in nature, and reflects an adaptive culture that allows their organisations to react to new situations and to meet new demands. They need to know what it is the military wants so that they can get on with providing it. Governments and their agencies, and local communities, have their own challenges to overcome, as do industry and infrastructure leaders. Routine consultation as well as sharing of concepts and plans will be required to enable these groups to contribute to overcoming logistics and infrastructure hurdles. Providing incentives for results might also be a consideration, if not a necessary step.

“The third group of views comes from the defence analysts and commentators who often observe the occasional non-communication between the other two groups, and are not necessarily beholden to balancing a perception of need against the availability of resources. It goes without saying that a range of views on Australia’s strategic infrastructure is important given Australia’s strategic circumstances. Such views may offer valuable alternatives to conventional planning. Naturally, self-discipline is required so that conversations don’t become ‘all care with little responsibility’.

“What all can agree on is that an investment in military capability must come with an investment in strategic infrastructure and logistics support. It doesn’t matter whether logistics come from a military or a civilian origin, but it does matter that all involved know what resources are coming from which source and what infrastructure is available to maximise their use.

“A national-level conversation on civil–military cooperation, strategic support arrangements for contingencies, and whole-of-nation preparedness is warranted after the defence strategic review. Without such analysis, it’s reasonable to expect that logistics and infrastructure will launch from the back of our minds to the front of them—at a time we can ill afford.”.

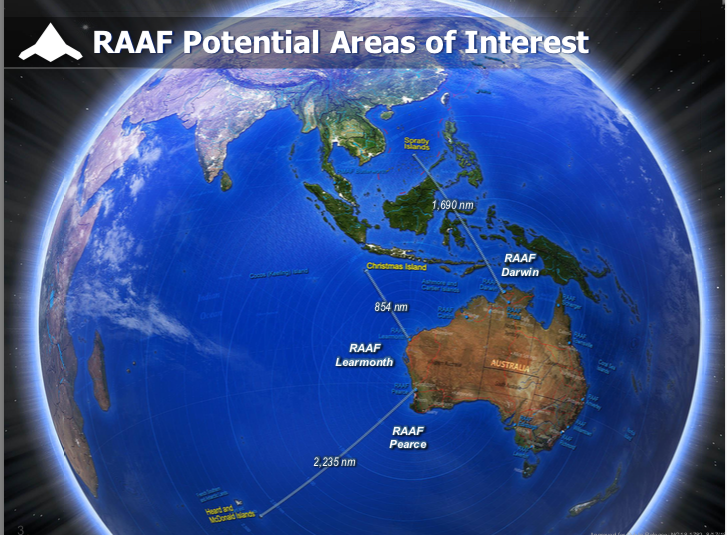

The featured graphic is from my September 2018 Williams Foundation Report which began a very serious relook at the way ahead for the ADF.