By Robbin Laird

Dateline: Canberra, Australia

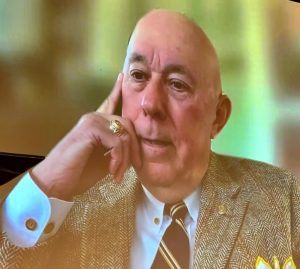

Recently, General “Buzz” Moseley spoke via video link to the May 22, 2025 seminar held by the Sir Richard Williams Foundation in Canberra, Australia.

General Moseley was the 18th Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force. Moseley was a distinguished war fighter who lived in the world as it is rather than the world we hoped to see. His entire service was focused on how the USAF could contribute to the deterrence of conflict but win it if you must fight.

I knew him when I worked for the Secretary of the Air Force, Michael W. Wynne, and the two of them formed one of the most remarkable pairings of defense leaders in my lifetime.

They were fired by the then Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates because of their opposition to the path Gates preferred which was to move from the way ahead for an air force built around air superiority to one that was not.

The significance of their firing was historic, a fact not lost on the late Senator Molan, whom I had the privilege to know and to discuss many things with him, including this event with him.

This is what the retired Australian General and Senator Jim Molan in his 2022 book on the need for Australia to deal with the China challenge:

“The U.S. is surfacing from decades of war in the Middle East with worn-out equipment, understandably having allocated a lot of its funding to ‘today’s wars’ rather than investing in the future. During the Iraq War, for instance, Secretary of Defense Bob Gates wanted more drones to carry on the day-to-day fight in Iraq and found himself in conflict with the U.S. Air Force, which wanted to continue building the fighters and bombers that it thought would be needed in the future.

“Gates sacked the chief of the U.S. Air Force and restricted the production of aircraft such as the stealth F-22 fighter and the B-21 bomber, in order to build the drones and other aircraft he needed.

“The result was that only a limited number of the extraordinary F-22s were built and the B-21 is still not in production. The impact of diverted spending and focus will be felt for a long time to come.

“The likely war with China, if it is ever fought by weapons of this type, is going to be fought by a very small number of modern stealth fighters, but mainly by U.S. fighters and bombers that are 20 to 30 years old.

“The result of all this is that the U.S. will not be able to marshal sufficient military power to deter China in the Western Pacific, possibly for years.”[1]

I have written about this and many other items related to shaping an effective force for the strategic age we are in in a book about the work of Secretary Wynne entitled: America, Global Military Competition, and Opportunities Lost.

The point is we are playing catch up in the face of the rise of the multipolar world, a world in which airpower matters even more than when Moseley was the Chief.

In providing the opening remarks to the seminar, General Moseley began his analysis by contrasting today’s threat landscape with the relative simplicity of the Cold War era. “Think about 50 years ago, 60 years ago, there was a major threat. Now there are multiple threats,” he observed, highlighting the emergence of what he sees as an unprecedented coalition of adversaries.

Unlike the bipolar world of the past, today’s security challenges involve China’s assertiveness, Russia’s aggression, Iran’s support for global terrorism, and North Korea’s unpredictable behavior. More concerning, according to Moseley, is that “these folks seem to be collaborating and cooperating with each other, sharing munitions, sharing munition stocks.” This cooperation represents a fundamental shift that complicates traditional deterrence strategies.

The general’s assessment extends beyond state actors to include transnational criminal organizations affecting border security, particularly along the U.S.-Mexico border. This multi-faceted threat environment, he argues, requires a robust and capable air force to maintain the rules-based international order that has underpinned Western security for decades.

Perhaps the most startling revelation in Moseley’s presentation was the current state of U.S. Air Force readiness. The statistics Moseley presented are concerning: ten different aircraft types that first flew over 50 years ago still comprise approximately two-thirds of the Air Force’s total fleet of 2,600 aircraft. The KC-135 tanker, a workhorse of military operations, began delivery during the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations.

This aging fleet problem is compounded by nearly four decades of continuous deployment. Since the early 1990s, when the first aircraft deployed to Saudi Arabia’s eastern province, American air power has maintained a persistent presence in the Middle East. The cumulative effect has been devastating to equipment readiness and personnel morale.

The Budget Reality

Moseley’s analysis of defense spending reveals a fundamental mismatch between mission requirements and available resources. With defense budgets hovering around 3% of GDP, he argued for a baseline of 4-4.5% under normal circumstances, and closer to 5-5.5% given the current recapitalization needs across all services.

The budget structure itself presents challenges. Approximately 50% of Air Force funding goes to personnel costs – necessary and appropriate but leaving limited resources for modernization. After accounting for infrastructure, operations, and maintenance costs for aging aircraft, the investment account that funds new capabilities consistently bears the brunt of budget cuts.

Moseley revealed that since 9/11, the Army has received $65 billion annually from Air Force and Navy budgets – representing over a trillion dollars in shifted priorities that he suggests weakened air capabilities during a critical period.

Central to Moseley’s argument is the primacy of air and space superiority as the Air Force’s fundamental mission. While the service has five core mission areas – air and space superiority, intelligence/surveillance/reconnaissance, rapid mobility, global strike, and command and control – he emphasized that the first enables all others.

“What happens to those service components inside those strategic commons, or those operative domains, if the Air Force does not get air and space superiority?” Moseley asked rhetorically. “What happens to freedom of movement on the surface? What happens to movement to place? What happens to the logistics baseline?”

This perspective challenges recent discussions within Air Force leadership about whether air superiority remains affordable or achievable. Moseley’s response is unequivocal: it’s not just affordable, it’s essential for all joint operations.

The Drone Debate: Promise and Peril

While acknowledging his role in pioneering unmanned systems – he commanded the first drone wing with minimal resources and a squadron commander who had “no people, no money,” just “a folding card table and a blender” for making margaritas while figuring out operations – Moseley expressed concern about current enthusiasm for replacing manned aircraft entirely.

His skepticism is grounded in practical experience. Drawing parallels to dropped cell phone calls, he questioned the wisdom of relying on data links for platforms operating at high altitude and speed in contested environments. “I’m not willing to put something 9000 feet [away] in and out of weather at night that’s running with me at 1.4 Mach that I can’t keep a link to.”

The general’s vision for unmanned systems is more nuanced. He sees value in “little buddies” that can accompany manned fighters to suppress integrated air defense systems but remains nervous about autonomous air-to-air combat in crowded airspace. His 2005 priorities for the Air Force Chief Scientist, the legendary Mark Lewis, included hypersonic weapons, directed energy systems, and drones that could “run with the fighters” – but as supplements, not replacements.

Moseley concluded his remarks by pointing to recent military operations that demonstrate the continued relevance of manned air power. Israeli strikes in Iran, operations in Yemen, and the destruction of Iraqi Republican Guard divisions during Operation Iraqi Freedom all underscore that reports of manned aircraft’s obsolescence are greatly exaggerated.

His broader message resonates beyond U.S. borders. The challenges he described – aging fleets, budget pressures, technological transitions, and complex threat environments – face many Western air forces. His emphasis on maintaining service identity while building joint capabilities offers a framework for allied cooperation without losing essential military expertise.

General Moseley’s presentation serves as both warning and roadmap.

The warning is clear: current trends in force structure, readiness, and strategic thinking threaten the air superiority that has underpinned Western military dominance for generations.

The roadmap emphasizes returning to basics – understanding core missions, properly funding modernization, and maintaining the technological edge that air power requires.

His closing observation was I think particularly poignant: “Officers and NCOs are not born joint. They become joint. They’re born a soldier, a sailor, an airman.”

This insight challenges current thinking that views service identity as an obstacle to joint operations, instead positioning it as the foundation upon which effective joint capabilities are built.

The stakes, as Moseley makes clear, extend far beyond military readiness. They encompass the ability to deter aggression, work together effectively as allies, and allows what used to be called the West to deal effectively with the rise of the multi-polar authoritarian world.

Note About General Moseley: General “Buzz” Moseley played a significant role in Operation Iraqi Freedom, serving as the Combined Forces Air Component Commander (JFACC). He was responsible for all aspects of aerial operations, including mission planning, air tasking orders, and airspace management, and oversaw a large number of personnel and assets.

General Moseley successfully integrated joint and coalition forces, including those from the Royal Saudi Air Force, Royal Air Force, and Royal Australian Air Force, into a cohesive air campaign.

He was involved in the planning and execution of numerous missions, including those targeting Iraqi regime leaders and infrastructure, and those supporting ground forces.

General Moseley was known for his leadership and vision, and his ability to inspire and motivate his troops. He also served as a role model for other military leaders, and his accomplishments were recognized with numerous awards, including two Defense Distinguished Service Medals.

[1] . Jim Molan. Danger On Our Doorstep (pp. 106-107). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.